The Multidimensional Battery of Prosody Perception (MBOPP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Segments

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Studies in Second Language Acquisition , 2014, 0 , 1 – 12 . doi:10.1017/S0272263114000138 BEYOND SEGMENTS Prosody in SLA QA Ineke Mennen Bangor University Esther de Leeuw AQ1 Queen Mary , University of London Mastering the pronunciation of a second language (L2) is considered extremely diffi cult, and few individuals succeed in sounding like a native speaker when learning a L2 in adulthood (Bongaerts, Van Summeren, Planken, & Schils, 1997 ; Scovel, 2000 ). Successful L2 pronunciation involves not only learning how to authentically produce all the indi- vidual sounds of the target language but also the acquisition of the L2’s unique prosody, such as its intonation, stress, rhythm, tone, and tempo. Transfer from the fi rst language (L1) is thought to be particularly persistent in prosody; L1 prosodic infl uences can remain present even after years of experience with the L2 (Mennen, 2004 ; Pickering, 2004 ). Research suggests that nontargetlike prosody in a L2 plays an important and independent role in the perception of foreign accentedness and in native-listener judgments of comprehensibility (Jilka, 2000 ; Magen, 1998 ; Munro, 1995 ; Trofi movich & Baker, 2006 ). Some research even suggests that prosody is more important than segments in such perceptions The idea of putting together this special issue originated during a workshop on L2 prosody at Bangor University organized by the fi rst author. We would like to thank all participants of that workshop for the enthusiasm with which this idea was received. We wish to express our sincere thanks to all of the authors for their excellent contributions to this issue and to the SSLA editorial team for all their help in bringing this issue to completion. -

Download Article (PDF)

Libri Phonetica 1999;56:105–107 = Part I, ‘Introduction’, includes a single Winifred Strange chapter written by the editor. It is an Speech Perception and Linguistic excellent historical review of cross-lan- Experience: Issues in Cross-Language guage studies in speech perception pro- Research viding a clear conceptual framework of York Press, Timonium, 1995 the topic. Strange presents a selective his- 492 pp.; $ 59 tory of research that highlights the main ISBN 0–912752–36–X theoretical themes and methodological paradigms. It begins with a brief descrip- How is speech perception shaped by tion of the basic phenomena that are the experience with our native language and starting points for the investigation: the by exposure to subsequent languages? constancy problem and the question of This is a central research question in units of analysis in speech perception. language perception, which emphasizes Next, the author presents the principal the importance of crosslinguistic studies. theories, methods, findings and limita- Speech Perception and Linguistic Experi- tions in early cross-language research, ence: Issues in Cross-Language Research focused on categorical perception as the contains the contributions to a Workshop dominant paradigm in the study of adult in Cross-Language Perception held at the and infant perception in the 1960s and University of South Florida, Tampa, Fla., 1970s. Finally, Strange reviews the most USA, in May 1992. important findings and conclusions in This text may be said to represent recent cross-language research (1980s and the first compilation strictly focused on early 1990s), which yielded a large theoretical and methodological issues of amount of new information from a wider cross-language perception research. -

Wokshop on Developing an International Prosodic Alphabet (Ipra) Within the AM Framework

Wokshop on developing an International Prosodic Alphabet (IPrA) within the AM framework SunSun----AhAh JunJun, UCLA JosJosJoséJos éééIgnacio HualdeHualde, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Pilar PrietoPrieto, ICREA – Universitat Pompeu Fabra Outline 1. Introduction & the motivations for developing the IPrA (Jun, Hualde, Prieto) 2. Proposals on labels of ---Pitch accents (Prieto) ---Phrasal/Boundary tones (Jun) ---NonNon- ---f0f0 features (Hualde) Part 1 Introduction & the motivations for developing the IPrA (by Sun-Ah Jun) Transcription system of intonation and prosodic structure in AM framework • ToBI (Tones and Break Indices) is a consensus system for labelling spoken utterances to mark phonologically contrastive intonational events and prosodic structure based on the Autosegmental-Metrical model of intonational phonology (e.g., Pierrehumbert 1980, Beckman & Pierrehumbert 1986, Ladd 1996/2008). • It was originally designed for English (1994), but has become a general framework for the development of prosodic annotation systems at the phonological level Various ToBI systems/AM models of intonation • Models of intonational phonology and ToBI annotation systems have been developed independently for dozens of typologically diverse languages (e.g., edited books by Jun 2005, 2014, Frota & Prieto 2015). ToBI is language-specific, not an IPA for prosody. •The ToBI system proposed for each language is assumed to be based on a well-established body of research on intonational phonology of that language. “ToBI is not an IPA for prosody. Each ToBI is specific to a language variety and the community of researchers working on the language variety” •Prosodic systems of various languages analyzed and described in the same framework allowed us to compare the systems across languages, i.e., prosodic typology Prosodic Typology • Classification of languages based on their prosody. -

Persistence of Prosody Shigeto Kawahara & Jason A

Persistence of prosody Shigeto Kawahara & Jason A. Shaw Keio University & Yale University Preamble In October 2016, at a workshop held at the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL),1 Junko and Armin presented a talk in which they argued against Kubozono’s (1999; 2003) proposal that VVN sequences in Japanese are syllabified as two separate syllables (V.VN) (Ito & Mester, 2016a). One of their arguments involved the consequences for VNC sequences (e.g. /beruriNkko/ ‘people from Berlin’); more specifically, Kubozono’s proposal would require positing syllables headed by a nasal (i.e. V.NC, or [be.ru.ri.Nk.ko]). They argue that syllables headed by a nasal segment are “questionable syllable types”, at least in the context of Japanese phonology. We are happy to dedicate this paper to Junko and Armin, in which we argue that Japanese has syllables headed by a fricative, and possibly those headed by an affricate. 1 Introduction Segments or prosody, which comes first? This question has been an important topic in phonetic and phonological theories. A classic view in generative phonology is that input segments are given first, and syllables and higher prosodic structures are built over segments according to universal and language-specific algorithms (Clements & Keyser 1983; Ito 1986; Kahn 1976; Steriade 1982 and subsequent research). An almost standard assumption in this line of research is that syllabification does not exist in the underlying representation (Blevins, 1995; Clements, 1986; Hayes, 1989), and this assumption reflects the view that segments come before prosody.2 However, there are also proposals to the effect that prosodic templates are given first, and segments are “filled in” later; such is the case for patterns of prosodic morphology, such as reduplication and truncation (Ito, 1990; Levin, 1985; Marantz, 1982; McCarthy, 1981; McCarthy & Prince, 1986, 1990; Mester, 1990). -

Relations Between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations

14 Relations between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations Willem J. M. Levelt One Agent, Two Modalities There is a famous book that never appeared: Bever and Weksel (shelved). It contained chapters by several young Turks in the budding new psycho- linguistics community of the mid-1960s. Jacques Mehler’s chapter (coau- thored with Harris Savin) was entitled “Language Users.” A normal language user “is capable of producing and understanding an infinite number of sentences that he has never heard before. The central problem for the psychologist studying language is to explain this fact—to describe the abilities that underlie this infinity of possible performances and state precisely how these abilities, together with the various details . of a given situation, determine any particular performance.” There is no hesi tation here about the psycholinguist’s core business: it is to explain our abilities to produce and to understand language. Indeed, the chapter’s purpose was to review the available research findings on these abilities and it contains, correspondingly, a section on the listener and another section on the speaker. This balance was quickly lost in the further history of psycholinguistics. With the happy and important exceptions of speech error and speech pausing research, the study of language use was factually reduced to studying language understanding. For example, Philip Johnson-Laird opened his review of experimental psycholinguistics in the 1974 Annual Review of Psychology with the statement: “The fundamental problem of psycholinguistics is simple to formulate: what happens if we understand sentences?” And he added, “Most of the other problems would be half way solved if only we had the answer to this question.” One major other 242 W. -

Colored-Speech Synaesthesia Is Triggered by Multisensory, Not Unisensory, Perception Gary Bargary,1,2,3 Kylie J

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Report Colored-Speech Synaesthesia Is Triggered by Multisensory, Not Unisensory, Perception Gary Bargary,1,2,3 Kylie J. Barnett,1,2,3 Kevin J. Mitchell,2,3 and Fiona N. Newell1,2 1School of Psychology, 2Institute of Neuroscience, and 3Smurfit Institute of Genetics, Trinity College Dublin ABSTRACT—Although it is estimated that as many as 4% of sistent terminology reflects an underlying lack of understanding people experience some form of enhanced cross talk be- about the amount of information processing required for syn- tween (or within) the senses, known as synaesthesia, very aesthesia to be induced. For example, several studies have little is understood about the level of information pro- found that synaesthesia can occur very rapidly (Palmeri, Blake, cessing required to induce a synaesthetic experience. In Marois, & Whetsell, 2002; Ramachandran & Hubbard, 2001; work presented here, we used a well-known multisensory Smilek, Dixon, Cudahy, & Merikle, 2001) and is sensitive to illusion called the McGurk effect to show that synaesthesia changes in low-level properties of the inducing stimulus, such as is driven by late, perceptual processing, rather than early, contrast (Hubbard, Manoha, & Ramachandran, 2006) or font unisensory processing. Specifically, we tested 9 linguistic- (Witthoft & Winawer, 2006). These findings suggest that syn- color synaesthetes and found that the colors induced by aesthesia is an automatic association driven by early, unisensory spoken words are related to what is perceived (i.e., the input. However, attention, semantic information, and feature- illusory combination of audio and visual inputs) and not to binding processes (Dixon, Smilek, Duffy, Zanna, & Merikle, the auditory component alone. -

Phonetic Encoding of Prosodic Structure

Keating: Phonetic encoding of prosody PHONETIC ENCODING OF PROSODIC STRUCTURE Patricia A. Keating Dept. of Linguistics, University of California, Los Angeles ABSTRACT: Speech production is highly sensitive to the prosodic organization of utterances. This paper reviews some of the ways in which articulation varies according to prosodic prominences and boundaries. INTRODUCTION Prosody is the organization of speech into a hierarchy of units or domains, some of which are more prominent than others. That is, prosody serves both a grouping function and a prominence marking function in speech. Prosody includes (1) phrasing, which refers to the various size groupings of smaller domains into larger ones, such as segments into syllables, syllables into words, or words into phrases; (2) stress, which refers to prominence of syllables at the word level; (3) accent, which refers to prominence at the phrase level; and distributions of tones (pitch events) associated with any of these, such as (4) lexical tones associated with syllables; or (5) intonational tones associated with phrases or accents. These various aspects of prosody together define and reflect the prosodic structure of an utterance. For the purposes of this paper, we can consider any one interval of speech that is grouped into a single prosodic domain and ask, At what level of prosodic structure does this domain occur? What speech events occur at the beginning and end of this domain? What is in the domains before and after this one? How prominent is this domain relative to those neighbours? All of this information will be relevant phonetically. The phonetic dimensions that are most obviously involved in realizing prosody are pitch, duration, and loudness, which are generally thought of as the suprasegmental dimensions. -

Perception and Awareness in Phonological Processing: the Case of the Phoneme

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/222609954 Perception and awareness in phonological processing: the case of the phoneme ARTICLE in COGNITION · APRIL 1994 Impact Factor: 3.63 · DOI: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90032-9 CITATIONS DOWNLOADS VIEWS 67 45 94 2 AUTHORS: José Morais Regine Kolinsky Université Libre de Bruxelles Université Libre de Bruxelles 92 PUBLICATIONS 1,938 CITATIONS 103 PUBLICATIONS 1,571 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Regine Kolinsky Retrieved on: 15 July 2015 Cognition, 50 (1994) 287-297 OOlO-0277/94/$07.00 0 1994 - Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Perception and awareness in phonological processing: the case of the phoneme JosC Morais*, RCgine Kolinsky Laboratoire de Psychologie exptrimentale, Universitt Libre de Bruxelles, Av. Ad. Buy1 117, B-l 050 Bruxelles, Belgium Abstract The necessity of a “levels-of-processing” approach in the study of mental repre- sentations is illustrated by the work on the psychological reality of the phoneme. On the basis of both experimental studies of human behavior and functional imaging data, it is argued that there are unconscious representations of phonemes in addition to conscious ones. These two sets of mental representations are func- tionally distinct: the former intervene in speech perception and (presumably) production; the latter are developed in the context of learning alphabetic literacy for both reading and writing purposes. Moreover, among phonological units and properties, phonemes may be the only ones to present a neural dissociation at the macro-anatomic level. Finally, it is argued that even if the representations used in speech perception and those used in assembling and in conscious operations are distinct, they may entertain dependency relations. -

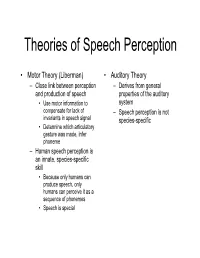

Theories of Speech Perception

Theories of Speech Perception • Motor Theory (Liberman) • Auditory Theory – Close link between perception – Derives from general and production of speech properties of the auditory • Use motor information to system compensate for lack of – Speech perception is not invariants in speech signal species-specific • Determine which articulatory gesture was made, infer phoneme – Human speech perception is an innate, species-specific skill • Because only humans can produce speech, only humans can perceive it as a sequence of phonemes • Speech is special Wilson & friends, 2004 • Perception • Production • /pa/ • /pa/ •/gi/ •/gi/ •Bell • Tap alternate thumbs • Burst of white noise Wilson et al., 2004 • Black areas are premotor and primary motor cortex activated when subjects produced the syllables • White arrows indicate central sulcus • Orange represents areas activated by listening to speech • Extensive activation in superior temporal gyrus • Activation in motor areas involved in speech production (!) Wilson and colleagues, 2004 Is categorical perception innate? Manipulate VOT, Monitor Sucking 4-month-old infants: Eimas et al. (1971) 20 ms 20 ms 0 ms (Different Sides) (Same Side) (Control) Is categorical perception species specific? • Chinchillas exhibit categorical perception as well Chinchilla experiment (Kuhl & Miller experiment) “ba…ba…ba…ba…”“pa…pa…pa…pa…” • Train on end-point “ba” (good), “pa” (bad) • Test on intermediate stimuli • Results: – Chinchillas switched over from staying to running at about the same location as the English b/p -

Effects of Language on Visual Perception

Effects of Language on Visual Perception Gary Lupyan1a, Rasha Abdel Rahmanb, Lera Boroditskyc, Andy Clarkd aUniversity of Wisconsin-Madison bHumboldt-Universität zu Berlin cUniversity of California San Diego dUniversity of Sussex Abstract Does language change what we perceive? Does speaking different languages cause us to perceive things differently? We review the behavioral and elec- trophysiological evidence for the influence of language on perception, with an emphasis on the visual modality. Effects of language on perception can be observed both in higher-level processes such as recognition, and in lower-level processes such as discrimination and detection. A consistent finding is that language causes us to perceive in a more categorical way. Rather than being fringe or exotic, as they are sometimes portrayed, we discuss how effects of language on perception naturally arise from the interactive and predictive nature of perception. Keywords: language; perception; vision; categorization; top-down effects; prediction “Even comparatively simple acts of perception are very much more at the mercy of the social patterns called words than we might suppose.” [1]. “No matter how influential language might be, it would seem preposter- ous to a physiologist that it could reach down into the retina and rewire the ganglion cells” [2]. 1Correspondence: [email protected] Preprint submitted to Trends in Cognitive Sciences August 22, 2020 Language as a form of experience that affects perception What factors influence how we perceive the world? For example, what makes it possible to recognize the object in Fig. 1a? Or to locate the ‘target’ in Fig. 1b? Where is the head of the bird in Fig. -

How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F

Language and Linguistics Compass 2/6 (2008): 1149–1170, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00089.x How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F. Werker University of British Columbia Abstract Perceiving the acoustic signal as a sequence of meaningful linguistic representations is a challenging task, which infants seem to accomplish effortlessly, despite the fact that they do not have a fully developed knowledge of language. The present article takes an integrative approach to infant speech perception, emphasizing how young learners’ perception of speech helps them acquire abstract structural properties of language. We introduce what is known about infants’ perception of language at birth. Then, we will discuss how perception develops during the first 2 years of life and describe some general perceptual mechanisms whose importance for speech perception and language acquisition has recently been established. To conclude, we discuss the implications of these empirical findings for language acquisition. 1. Introduction As part of our everyday life, we routinely interact with children and adults, women and men, as well as speakers using a dialect different from our own. We might talk to them face-to-face or on the phone, in a quiet room or on a busy street. Although the speech signal we receive in these situations can be physically very different (e.g., men have a lower-pitched voice than women or children), we usually have little difficulty understanding what our interlocutors say. Yet, this is no easy task, because the mapping from the acoustic signal to the sounds or words of a language is not straightforward. -

LX525: Prosody

LX525: Prosody Spring 2011 Tuesday, Thursday 11-12:30 Room: Kenmore Classroom Building 102 Instructor: Jonathan Barnes CAS Program in Linguistics Dept. of Romance Studies 621 Commonwealth Avenue, Room 119 617-353-6222 [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 9:30-11:30, Thursday 3:30-4:30, or by appointment Course Information: Text: There is no textbook required for this class. Instead, we will make use of a range of readings, mostly published articles in the areas we will cover. These will be distributed to you as the semester progresses. Text recommended: Some useful books in this area, especially for graduate students intending to go on this part of the field, include: Gussenhoven, Carlos. 2004. The Phonology of Tone and Intonation. Cambridge: CUP. Jun, Sun-Ah. 2005. Prosodic Typology: The Phonology of Intonation and Phrasing. Oxford: OUP. Ladd, D. Robert. 2008. Intonational Phonology. 2nd Edition. Cambridge: CUP. Other Resources: • The International Phonetic Alphabet for your computer: http://scripts.sil.org/IPAhome • Praat: http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/ • Wavesurfer: http://www.speech.kth.se/wavesurfer/ Course Requirements: Regular attendance and class participation (5% of grade) More-or-less weekly problem sets (30% of grade) Midterm exam – March 10 (15% of grade) 1 Final project (30% of grade) Final exam – Wednesday, May 11, 9:00-11:00 PM (20% of grade) Homework • Weekly homework assignments are due at the beginning of class on the day they are due. Late homework (without prior excuse) will not be accepted. Your lowest homework grade will be dropped. • You may, if you wish, collaborate with your fellow students on homework assignments.