Speech Perception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pg. 5 CHAPTER-2: MECHANISM of SPEECH PRODUCTION AND

Acoustic Analysis for Comparison and Identification of Normal and Disguised Speech of Individuals CHAPTER-2: MECHANISM OF SPEECH PRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1. Anatomy of speech production Speech is the vocal aspect of communication made by human beings. Human beings are able to express their ideas, feelings and emotions to the listener through speech generated using vocal articulators (NIDCD, June 2010). Development of speech is a constant process and requires a lot of practice. Communication is a string of events which allows the speaker to express their feelings and emotions and the listener to understand them. Speech communication is considered as a thought that is transformed into language for expression. Phil Rose & James R Robertson (2002) mentioned that voices of individuals are complex in nature. They aid in providing vital information related to sex, emotional state or age of the speaker. Although evidence from DNA always remains headlines, DNA can‟t talk. It can‟t be recorded planning, carrying out or confessing to a crime. It can‟t be so apparently directly incriminating. Perhaps, it is these features that contribute to interest and importance of forensic speaker identification. Speech signal is a multidimensional acoustic wave (as seen in figure 2.1.) which provides information about the words or message being spoken, speaker identity, language spoken, physical and mental health, race, age, sex, education level, religious orientation and background of an individual (Schetelig T. & Rabenstein R., May 1998). pg. 5 Acoustic Analysis for Comparison and Identification of Normal and Disguised Speech of Individuals Figure 2.1.: Representation of properties of sound wave (Courtesy "Waves". -

Phonological Use of the Larynx: a Tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière

Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière To cite this version: Jacqueline Vaissière. Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial. Larynx 97, 1994, Marseille, France. pp.115-126. halshs-00703584 HAL Id: halshs-00703584 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00703584 Submitted on 3 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Vaissière, J., (1997), "Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial", Larynx 97, Marseille, 115-126. PHONOLOGICAL USE OF THE LARYNX J. Vaissière UPRESA-CNRS 1027, Institut de Phonétique, Paris, France larynx used as a carrier of paralinguistic information . RÉSUMÉ THE PRIMARY FUNCTION OF THE LARYNX Cette communication concerne le rôle du IS PROTECTIVE larynx dans l'acte de communication. Toutes As stated by Sapir, 1923, les langues du monde utilisent des physiologically, "speech is an overlaid configurations caractéristiques du larynx, aux function, or to be more precise, a group of niveaux segmental, lexical, et supralexical. Nous présentons d'abord l'utilisation des différents types de phonation pour distinguer entre les consonnes et les voyelles dans les overlaid functions. It gets what service it can langues du monde, et également du larynx out of organs and functions, nervous and comme lieu d'articulation des glottales, et la muscular, that come into being and are production des éjectives et des implosives. -

Download Article (PDF)

Libri Phonetica 1999;56:105–107 = Part I, ‘Introduction’, includes a single Winifred Strange chapter written by the editor. It is an Speech Perception and Linguistic excellent historical review of cross-lan- Experience: Issues in Cross-Language guage studies in speech perception pro- Research viding a clear conceptual framework of York Press, Timonium, 1995 the topic. Strange presents a selective his- 492 pp.; $ 59 tory of research that highlights the main ISBN 0–912752–36–X theoretical themes and methodological paradigms. It begins with a brief descrip- How is speech perception shaped by tion of the basic phenomena that are the experience with our native language and starting points for the investigation: the by exposure to subsequent languages? constancy problem and the question of This is a central research question in units of analysis in speech perception. language perception, which emphasizes Next, the author presents the principal the importance of crosslinguistic studies. theories, methods, findings and limita- Speech Perception and Linguistic Experi- tions in early cross-language research, ence: Issues in Cross-Language Research focused on categorical perception as the contains the contributions to a Workshop dominant paradigm in the study of adult in Cross-Language Perception held at the and infant perception in the 1960s and University of South Florida, Tampa, Fla., 1970s. Finally, Strange reviews the most USA, in May 1992. important findings and conclusions in This text may be said to represent recent cross-language research (1980s and the first compilation strictly focused on early 1990s), which yielded a large theoretical and methodological issues of amount of new information from a wider cross-language perception research. -

Relations Between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations

14 Relations between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations Willem J. M. Levelt One Agent, Two Modalities There is a famous book that never appeared: Bever and Weksel (shelved). It contained chapters by several young Turks in the budding new psycho- linguistics community of the mid-1960s. Jacques Mehler’s chapter (coau- thored with Harris Savin) was entitled “Language Users.” A normal language user “is capable of producing and understanding an infinite number of sentences that he has never heard before. The central problem for the psychologist studying language is to explain this fact—to describe the abilities that underlie this infinity of possible performances and state precisely how these abilities, together with the various details . of a given situation, determine any particular performance.” There is no hesi tation here about the psycholinguist’s core business: it is to explain our abilities to produce and to understand language. Indeed, the chapter’s purpose was to review the available research findings on these abilities and it contains, correspondingly, a section on the listener and another section on the speaker. This balance was quickly lost in the further history of psycholinguistics. With the happy and important exceptions of speech error and speech pausing research, the study of language use was factually reduced to studying language understanding. For example, Philip Johnson-Laird opened his review of experimental psycholinguistics in the 1974 Annual Review of Psychology with the statement: “The fundamental problem of psycholinguistics is simple to formulate: what happens if we understand sentences?” And he added, “Most of the other problems would be half way solved if only we had the answer to this question.” One major other 242 W. -

Colored-Speech Synaesthesia Is Triggered by Multisensory, Not Unisensory, Perception Gary Bargary,1,2,3 Kylie J

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Report Colored-Speech Synaesthesia Is Triggered by Multisensory, Not Unisensory, Perception Gary Bargary,1,2,3 Kylie J. Barnett,1,2,3 Kevin J. Mitchell,2,3 and Fiona N. Newell1,2 1School of Psychology, 2Institute of Neuroscience, and 3Smurfit Institute of Genetics, Trinity College Dublin ABSTRACT—Although it is estimated that as many as 4% of sistent terminology reflects an underlying lack of understanding people experience some form of enhanced cross talk be- about the amount of information processing required for syn- tween (or within) the senses, known as synaesthesia, very aesthesia to be induced. For example, several studies have little is understood about the level of information pro- found that synaesthesia can occur very rapidly (Palmeri, Blake, cessing required to induce a synaesthetic experience. In Marois, & Whetsell, 2002; Ramachandran & Hubbard, 2001; work presented here, we used a well-known multisensory Smilek, Dixon, Cudahy, & Merikle, 2001) and is sensitive to illusion called the McGurk effect to show that synaesthesia changes in low-level properties of the inducing stimulus, such as is driven by late, perceptual processing, rather than early, contrast (Hubbard, Manoha, & Ramachandran, 2006) or font unisensory processing. Specifically, we tested 9 linguistic- (Witthoft & Winawer, 2006). These findings suggest that syn- color synaesthetes and found that the colors induced by aesthesia is an automatic association driven by early, unisensory spoken words are related to what is perceived (i.e., the input. However, attention, semantic information, and feature- illusory combination of audio and visual inputs) and not to binding processes (Dixon, Smilek, Duffy, Zanna, & Merikle, the auditory component alone. -

Perception and Awareness in Phonological Processing: the Case of the Phoneme

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/222609954 Perception and awareness in phonological processing: the case of the phoneme ARTICLE in COGNITION · APRIL 1994 Impact Factor: 3.63 · DOI: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90032-9 CITATIONS DOWNLOADS VIEWS 67 45 94 2 AUTHORS: José Morais Regine Kolinsky Université Libre de Bruxelles Université Libre de Bruxelles 92 PUBLICATIONS 1,938 CITATIONS 103 PUBLICATIONS 1,571 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Regine Kolinsky Retrieved on: 15 July 2015 Cognition, 50 (1994) 287-297 OOlO-0277/94/$07.00 0 1994 - Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Perception and awareness in phonological processing: the case of the phoneme JosC Morais*, RCgine Kolinsky Laboratoire de Psychologie exptrimentale, Universitt Libre de Bruxelles, Av. Ad. Buy1 117, B-l 050 Bruxelles, Belgium Abstract The necessity of a “levels-of-processing” approach in the study of mental repre- sentations is illustrated by the work on the psychological reality of the phoneme. On the basis of both experimental studies of human behavior and functional imaging data, it is argued that there are unconscious representations of phonemes in addition to conscious ones. These two sets of mental representations are func- tionally distinct: the former intervene in speech perception and (presumably) production; the latter are developed in the context of learning alphabetic literacy for both reading and writing purposes. Moreover, among phonological units and properties, phonemes may be the only ones to present a neural dissociation at the macro-anatomic level. Finally, it is argued that even if the representations used in speech perception and those used in assembling and in conscious operations are distinct, they may entertain dependency relations. -

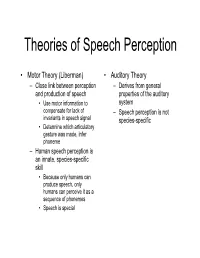

Theories of Speech Perception

Theories of Speech Perception • Motor Theory (Liberman) • Auditory Theory – Close link between perception – Derives from general and production of speech properties of the auditory • Use motor information to system compensate for lack of – Speech perception is not invariants in speech signal species-specific • Determine which articulatory gesture was made, infer phoneme – Human speech perception is an innate, species-specific skill • Because only humans can produce speech, only humans can perceive it as a sequence of phonemes • Speech is special Wilson & friends, 2004 • Perception • Production • /pa/ • /pa/ •/gi/ •/gi/ •Bell • Tap alternate thumbs • Burst of white noise Wilson et al., 2004 • Black areas are premotor and primary motor cortex activated when subjects produced the syllables • White arrows indicate central sulcus • Orange represents areas activated by listening to speech • Extensive activation in superior temporal gyrus • Activation in motor areas involved in speech production (!) Wilson and colleagues, 2004 Is categorical perception innate? Manipulate VOT, Monitor Sucking 4-month-old infants: Eimas et al. (1971) 20 ms 20 ms 0 ms (Different Sides) (Same Side) (Control) Is categorical perception species specific? • Chinchillas exhibit categorical perception as well Chinchilla experiment (Kuhl & Miller experiment) “ba…ba…ba…ba…”“pa…pa…pa…pa…” • Train on end-point “ba” (good), “pa” (bad) • Test on intermediate stimuli • Results: – Chinchillas switched over from staying to running at about the same location as the English b/p -

Effects of Language on Visual Perception

Effects of Language on Visual Perception Gary Lupyan1a, Rasha Abdel Rahmanb, Lera Boroditskyc, Andy Clarkd aUniversity of Wisconsin-Madison bHumboldt-Universität zu Berlin cUniversity of California San Diego dUniversity of Sussex Abstract Does language change what we perceive? Does speaking different languages cause us to perceive things differently? We review the behavioral and elec- trophysiological evidence for the influence of language on perception, with an emphasis on the visual modality. Effects of language on perception can be observed both in higher-level processes such as recognition, and in lower-level processes such as discrimination and detection. A consistent finding is that language causes us to perceive in a more categorical way. Rather than being fringe or exotic, as they are sometimes portrayed, we discuss how effects of language on perception naturally arise from the interactive and predictive nature of perception. Keywords: language; perception; vision; categorization; top-down effects; prediction “Even comparatively simple acts of perception are very much more at the mercy of the social patterns called words than we might suppose.” [1]. “No matter how influential language might be, it would seem preposter- ous to a physiologist that it could reach down into the retina and rewire the ganglion cells” [2]. 1Correspondence: [email protected] Preprint submitted to Trends in Cognitive Sciences August 22, 2020 Language as a form of experience that affects perception What factors influence how we perceive the world? For example, what makes it possible to recognize the object in Fig. 1a? Or to locate the ‘target’ in Fig. 1b? Where is the head of the bird in Fig. -

How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F

Language and Linguistics Compass 2/6 (2008): 1149–1170, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00089.x How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F. Werker University of British Columbia Abstract Perceiving the acoustic signal as a sequence of meaningful linguistic representations is a challenging task, which infants seem to accomplish effortlessly, despite the fact that they do not have a fully developed knowledge of language. The present article takes an integrative approach to infant speech perception, emphasizing how young learners’ perception of speech helps them acquire abstract structural properties of language. We introduce what is known about infants’ perception of language at birth. Then, we will discuss how perception develops during the first 2 years of life and describe some general perceptual mechanisms whose importance for speech perception and language acquisition has recently been established. To conclude, we discuss the implications of these empirical findings for language acquisition. 1. Introduction As part of our everyday life, we routinely interact with children and adults, women and men, as well as speakers using a dialect different from our own. We might talk to them face-to-face or on the phone, in a quiet room or on a busy street. Although the speech signal we receive in these situations can be physically very different (e.g., men have a lower-pitched voice than women or children), we usually have little difficulty understanding what our interlocutors say. Yet, this is no easy task, because the mapping from the acoustic signal to the sounds or words of a language is not straightforward. -

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism I. MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION A. MUSCLES OF INHALATION (muscles that enlarge the thoracic cavity) 1. Diaphragm Attachments: The diaphragm originates in a number of places: the lower tip of the sternum; the first 3 or 4 lumbar vertebrae and the lower borders and inner surfaces of the cartilages of ribs 7 - 12. All fibers insert into a central tendon (aponeurosis of the diaphragm). Function: Contraction of the diaphragm draws the central tendon down and forward, which enlarges the thoracic cavity vertically. It can also elevate to some extent the lower ribs. The diaphragm separates the thoracic and the abdominal cavities. 2. External Intercostals Attachments: The external intercostals run from the lip on the lower border of each rib inferiorly and medially to the upper border of the rib immediately below. Function: These muscles may have several functions. They serve to strengthen the thoracic wall so that it doesn't bulge between the ribs. They provide a checking action to counteract relaxation pressure. Because of the direction of attachment of their fibers, the external intercostals can raise the thoracic cage for inhalation. 3. Pectoralis Major Attachments: This muscle attaches on the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle, the sternum and costal cartilages 1-6 or 7. All fibers come together and insert at the greater tubercle of the humerus. Function: Pectoralis major is primarily an abductor of the arm. It can, however, serve as a supplemental (or compensatory) muscle of inhalation, raising the rib cage and sternum. (In other words, breathing by raising and lowering the arms!) It is mentioned here chiefly because it is encountered in the dissection. -

Illustrating the Production of the International Phonetic Alphabet

INTERSPEECH 2016 September 8–12, 2016, San Francisco, USA Illustrating the Production of the International Phonetic Alphabet Sounds using Fast Real-Time Magnetic Resonance Imaging Asterios Toutios1, Sajan Goud Lingala1, Colin Vaz1, Jangwon Kim1, John Esling2, Patricia Keating3, Matthew Gordon4, Dani Byrd1, Louis Goldstein1, Krishna Nayak1, Shrikanth Narayanan1 1University of Southern California 2University of Victoria 3University of California, Los Angeles 4University of California, Santa Barbara ftoutios,[email protected] Abstract earlier rtMRI data, such as those in the publicly released USC- TIMIT [5] and USC-EMO-MRI [6] databases. Recent advances in real-time magnetic resonance imaging This paper presents a new rtMRI resource that showcases (rtMRI) of the upper airway for acquiring speech production these technological advances by illustrating the production of a data provide unparalleled views of the dynamics of a speaker’s comprehensive set of speech sounds present across the world’s vocal tract at very high frame rates (83 frames per second and languages, i.e. not restricted to English, encoded as conso- even higher). This paper introduces an effort to collect and nant and vowel symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet make available on-line rtMRI data corresponding to a large sub- (IPA), which was devised by the International Phonetic Asso- set of the sounds of the world’s languages as encoded in the ciation as a standardized representation of the sounds of spo- International Phonetic Alphabet, with supplementary English ken language [7]. These symbols are meant to represent unique words and phonetically-balanced texts, produced by four promi- speech sounds, and do not correspond to the orthography of any nent phoneticians, using the latest rtMRI technology. -

Articulatory Phonetics

Articulatory Phonetics Lecturer: Dr Anna Sfakianaki HY578 Digital Speech Signal Processing Spring Term 2016-17 CSD University of Crete What is Phonetics? n Phonetics is a branch of Linguistics that systematically studies the sounds of human speech. 1. How speech sounds are produced Production (Articulation) 2. How speech sounds are transmitted Acoustics 3. How speech sounds are received Perception It is an interdisciplinary subject, theoretical as much as experimental. Why do speech engineers need phonetics? n An engineer working on speech signal processing usually ignores the linguistic background of the speech he/she analyzes. (Olaszy, 2005) ¡ How was the utterance planned in the speaker’s brain? ¡ How was it produced by the speaker’s articulation organs? ¡ What sort of contextual influences did it receive? ¡ How will the listener decode the message? Phonetics in Speech Engineering Combined knowledge of articulatory gestures and acoustic properties of speech sounds Categorization of speech sounds Segmentation Speech Database Annotation Algorithms Speech Recognition Speech Synthesis Phonetics in Speech Engineering Speech • diagnosis Disorders • treatment Pronunciation • L2 Teaching Tools • Foreign languages Speech • Hearing aids Intelligibility Enhancement • Other tools A week with a phonetician… n Tuesday n Thursday Articulatory Phonetics Acoustic Phonetics ¡ Speech production ¡ Formants ¡ Sound waves ¡ Fundamental Frequency ¡ Places and manners of articulation ¡ Acoustics of Vowels n Consonants & Vowels n Articulatory vs Acoustic charts ¡ Waveforms of consonants - VOT ¡ Acoustics of Consonants n Formant Transitions ¡ Suprasegmentals n Friday More Acoustic Phonetics… ¡ Interpreting spectrograms ¡ The guessing game… ¡ Individual Differences Peter Ladefoged Home Page: n Professor UCLA (1962-1991) http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/ladefoge/ n Travelled in Europe, Africa, India, China, Australia, etc.