Perception and Awareness in Phonological Processing: the Case of the Phoneme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article (PDF)

Libri Phonetica 1999;56:105–107 = Part I, ‘Introduction’, includes a single Winifred Strange chapter written by the editor. It is an Speech Perception and Linguistic excellent historical review of cross-lan- Experience: Issues in Cross-Language guage studies in speech perception pro- Research viding a clear conceptual framework of York Press, Timonium, 1995 the topic. Strange presents a selective his- 492 pp.; $ 59 tory of research that highlights the main ISBN 0–912752–36–X theoretical themes and methodological paradigms. It begins with a brief descrip- How is speech perception shaped by tion of the basic phenomena that are the experience with our native language and starting points for the investigation: the by exposure to subsequent languages? constancy problem and the question of This is a central research question in units of analysis in speech perception. language perception, which emphasizes Next, the author presents the principal the importance of crosslinguistic studies. theories, methods, findings and limita- Speech Perception and Linguistic Experi- tions in early cross-language research, ence: Issues in Cross-Language Research focused on categorical perception as the contains the contributions to a Workshop dominant paradigm in the study of adult in Cross-Language Perception held at the and infant perception in the 1960s and University of South Florida, Tampa, Fla., 1970s. Finally, Strange reviews the most USA, in May 1992. important findings and conclusions in This text may be said to represent recent cross-language research (1980s and the first compilation strictly focused on early 1990s), which yielded a large theoretical and methodological issues of amount of new information from a wider cross-language perception research. -

Relations Between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations

14 Relations between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations Willem J. M. Levelt One Agent, Two Modalities There is a famous book that never appeared: Bever and Weksel (shelved). It contained chapters by several young Turks in the budding new psycho- linguistics community of the mid-1960s. Jacques Mehler’s chapter (coau- thored with Harris Savin) was entitled “Language Users.” A normal language user “is capable of producing and understanding an infinite number of sentences that he has never heard before. The central problem for the psychologist studying language is to explain this fact—to describe the abilities that underlie this infinity of possible performances and state precisely how these abilities, together with the various details . of a given situation, determine any particular performance.” There is no hesi tation here about the psycholinguist’s core business: it is to explain our abilities to produce and to understand language. Indeed, the chapter’s purpose was to review the available research findings on these abilities and it contains, correspondingly, a section on the listener and another section on the speaker. This balance was quickly lost in the further history of psycholinguistics. With the happy and important exceptions of speech error and speech pausing research, the study of language use was factually reduced to studying language understanding. For example, Philip Johnson-Laird opened his review of experimental psycholinguistics in the 1974 Annual Review of Psychology with the statement: “The fundamental problem of psycholinguistics is simple to formulate: what happens if we understand sentences?” And he added, “Most of the other problems would be half way solved if only we had the answer to this question.” One major other 242 W. -

Colored-Speech Synaesthesia Is Triggered by Multisensory, Not Unisensory, Perception Gary Bargary,1,2,3 Kylie J

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Report Colored-Speech Synaesthesia Is Triggered by Multisensory, Not Unisensory, Perception Gary Bargary,1,2,3 Kylie J. Barnett,1,2,3 Kevin J. Mitchell,2,3 and Fiona N. Newell1,2 1School of Psychology, 2Institute of Neuroscience, and 3Smurfit Institute of Genetics, Trinity College Dublin ABSTRACT—Although it is estimated that as many as 4% of sistent terminology reflects an underlying lack of understanding people experience some form of enhanced cross talk be- about the amount of information processing required for syn- tween (or within) the senses, known as synaesthesia, very aesthesia to be induced. For example, several studies have little is understood about the level of information pro- found that synaesthesia can occur very rapidly (Palmeri, Blake, cessing required to induce a synaesthetic experience. In Marois, & Whetsell, 2002; Ramachandran & Hubbard, 2001; work presented here, we used a well-known multisensory Smilek, Dixon, Cudahy, & Merikle, 2001) and is sensitive to illusion called the McGurk effect to show that synaesthesia changes in low-level properties of the inducing stimulus, such as is driven by late, perceptual processing, rather than early, contrast (Hubbard, Manoha, & Ramachandran, 2006) or font unisensory processing. Specifically, we tested 9 linguistic- (Witthoft & Winawer, 2006). These findings suggest that syn- color synaesthetes and found that the colors induced by aesthesia is an automatic association driven by early, unisensory spoken words are related to what is perceived (i.e., the input. However, attention, semantic information, and feature- illusory combination of audio and visual inputs) and not to binding processes (Dixon, Smilek, Duffy, Zanna, & Merikle, the auditory component alone. -

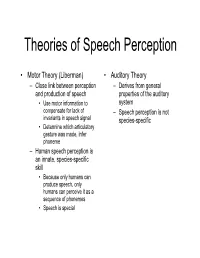

Theories of Speech Perception

Theories of Speech Perception • Motor Theory (Liberman) • Auditory Theory – Close link between perception – Derives from general and production of speech properties of the auditory • Use motor information to system compensate for lack of – Speech perception is not invariants in speech signal species-specific • Determine which articulatory gesture was made, infer phoneme – Human speech perception is an innate, species-specific skill • Because only humans can produce speech, only humans can perceive it as a sequence of phonemes • Speech is special Wilson & friends, 2004 • Perception • Production • /pa/ • /pa/ •/gi/ •/gi/ •Bell • Tap alternate thumbs • Burst of white noise Wilson et al., 2004 • Black areas are premotor and primary motor cortex activated when subjects produced the syllables • White arrows indicate central sulcus • Orange represents areas activated by listening to speech • Extensive activation in superior temporal gyrus • Activation in motor areas involved in speech production (!) Wilson and colleagues, 2004 Is categorical perception innate? Manipulate VOT, Monitor Sucking 4-month-old infants: Eimas et al. (1971) 20 ms 20 ms 0 ms (Different Sides) (Same Side) (Control) Is categorical perception species specific? • Chinchillas exhibit categorical perception as well Chinchilla experiment (Kuhl & Miller experiment) “ba…ba…ba…ba…”“pa…pa…pa…pa…” • Train on end-point “ba” (good), “pa” (bad) • Test on intermediate stimuli • Results: – Chinchillas switched over from staying to running at about the same location as the English b/p -

Effects of Language on Visual Perception

Effects of Language on Visual Perception Gary Lupyan1a, Rasha Abdel Rahmanb, Lera Boroditskyc, Andy Clarkd aUniversity of Wisconsin-Madison bHumboldt-Universität zu Berlin cUniversity of California San Diego dUniversity of Sussex Abstract Does language change what we perceive? Does speaking different languages cause us to perceive things differently? We review the behavioral and elec- trophysiological evidence for the influence of language on perception, with an emphasis on the visual modality. Effects of language on perception can be observed both in higher-level processes such as recognition, and in lower-level processes such as discrimination and detection. A consistent finding is that language causes us to perceive in a more categorical way. Rather than being fringe or exotic, as they are sometimes portrayed, we discuss how effects of language on perception naturally arise from the interactive and predictive nature of perception. Keywords: language; perception; vision; categorization; top-down effects; prediction “Even comparatively simple acts of perception are very much more at the mercy of the social patterns called words than we might suppose.” [1]. “No matter how influential language might be, it would seem preposter- ous to a physiologist that it could reach down into the retina and rewire the ganglion cells” [2]. 1Correspondence: [email protected] Preprint submitted to Trends in Cognitive Sciences August 22, 2020 Language as a form of experience that affects perception What factors influence how we perceive the world? For example, what makes it possible to recognize the object in Fig. 1a? Or to locate the ‘target’ in Fig. 1b? Where is the head of the bird in Fig. -

How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F

Language and Linguistics Compass 2/6 (2008): 1149–1170, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00089.x How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F. Werker University of British Columbia Abstract Perceiving the acoustic signal as a sequence of meaningful linguistic representations is a challenging task, which infants seem to accomplish effortlessly, despite the fact that they do not have a fully developed knowledge of language. The present article takes an integrative approach to infant speech perception, emphasizing how young learners’ perception of speech helps them acquire abstract structural properties of language. We introduce what is known about infants’ perception of language at birth. Then, we will discuss how perception develops during the first 2 years of life and describe some general perceptual mechanisms whose importance for speech perception and language acquisition has recently been established. To conclude, we discuss the implications of these empirical findings for language acquisition. 1. Introduction As part of our everyday life, we routinely interact with children and adults, women and men, as well as speakers using a dialect different from our own. We might talk to them face-to-face or on the phone, in a quiet room or on a busy street. Although the speech signal we receive in these situations can be physically very different (e.g., men have a lower-pitched voice than women or children), we usually have little difficulty understanding what our interlocutors say. Yet, this is no easy task, because the mapping from the acoustic signal to the sounds or words of a language is not straightforward. -

Speech Perception

UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2010) Chapter 5 (of Acoustic and Auditory Phonetics, 3rd Edition - in press) Speech perception When you listen to someone speaking you generally focus on understanding their meaning. One famous (in linguistics) way of saying this is that "we speak in order to be heard, in order to be understood" (Jakobson, Fant & Halle, 1952). Our drive, as listeners, to understand the talker leads us to focus on getting the words being said, and not so much on exactly how they are pronounced. But sometimes a pronunciation will jump out at you - somebody says a familiar word in an unfamiliar way and you just have to ask - "is that how you say that?" When we listen to the phonetics of speech - to how the words sound and not just what they mean - we as listeners are engaged in speech perception. In speech perception, listeners focus attention on the sounds of speech and notice phonetic details about pronunciation that are often not noticed at all in normal speech communication. For example, listeners will often not hear, or not seem to hear, a speech error or deliberate mispronunciation in ordinary conversation, but will notice those same errors when instructed to listen for mispronunciations (see Cole, 1973). --------begin sidebar---------------------- Testing mispronunciation detection As you go about your daily routine, try mispronouncing a word every now and then to see if the people you are talking to will notice. For instance, if the conversation is about a biology class you could pronounce it "biolochi". After saying it this way a time or two you could tell your friend about your little experiment and ask if they noticed any mispronounced words. -

Localising Foreign Accents in Speech Perception, Storage and Production

Localising foreign accents in speech perception, storage and production Yuki Asano Department of Linguistics, Faculty of Humanities University of Konstanz, Germany This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS) URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-0-386434 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their insightful comments, suggestions, questions, ideas, for this thesis Bettina Braun Ryoko Hayashi Aditi Lahiri René Kager For making my research project financially possible Bettina Braun The German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) The German National Academic Foundation University of Konstanz For their general interest, comments, and inspiring ideas Bettina Braun Miriam Butt Nicole Dehé Bijarke Frellesvig Rolf Grawert Janet Grijzenhout Michele Gubian Carlos Guessenhoven Ryoko Hayashi Bari¸sKabak René Kager iv Aditi Lahiri Frans Plank Dominik Sasha Giuseppina Turco For correcting my English Filippo Cervelli For their technical support Michele Gubian Joachim Kleinmann Dominik Sasha Research assistants For their attendance of my experiments Participants For trusting in my research potential Bettina Braun Masahiko & Kyoko Asano For their mental support Masahiko & Kyoko Asano Bettina Braun Emilia & Filippo Cervelli Hannelore & Rolf Grawert Thank you very much! ZUSAMMENFASSUNG Die Dissertationsschrift beschäftigt sich mit der Suche nach möglichen Quellen eines fremdsprachlichen Akzents in der Prosodie, insbesondere in F0 und segmentaler Län- ge. Anhand der in den Kapiteln 2 bis 4 dargestellten -

The Lexical Restructuring Hypothesis: Two Claims of PA Evaluated Michelle E

The Lexical Restructuring Hypothesis: Two Claims of PA Evaluated a Michelle E. Erskine, Tristan Mahr, Benjamin Munson , and Jan R. Edwards University of Wisconsin-Madison, aUniversity of Minnesota Introduction Methods & Analysis Results Results Nonword Repetition • Phonological awareness (PA) is an important skill for learning to Mediation Model 1 Mediation Model 2 Stimuli read (McBride-Chang, 1990; Cunningham & Stanovich, 1997). • 22 pairs of nonsense words adapted from Edwards et al., 2004 • A variety of factors including phonological working memory Blending Results: • Pairs included a 2-phoneme sequence that contrasted in (PWM), speech perception, and vocabulary skills have been shown • Consistent with complete mediation. phonotactic probability Vocabulary to be related to phonological awareness. • A boot-strapping method to evaluate mediation yields a • Presented stimuli matched child’s native dialect significant indirect effect of speech perception on PA, p < .001, • However, the relationships among these factors are not well and the direct effect of speech perception on PA is no longer understood. Procedure significant. • The lexical restructuring hypothesis proposes that the association • Nonwords were paired with a picture of an unfamiliar object in a • 94% of the effect of speech perception on PA is mediated by among PWM, speech perception and PA are secondary to vocabulary picture-prompted auditory-word-repetition task Phonological Phonological expressive vocabulary size. development in children. Working Memory Awareness • The direct effect of speech perception on PA is no longer • Thus, PA primarily emerges as a result of the gradual significant when the model accounts for effects of reorganization of the lexicon and, to a lesser degree, the vocabulary size. -

A Visualization Scheme for Complex Spectrograms with Complete Amplitude and Phase Information

2016 3rd International Conference on Smart Materials and Nanotechnology in Engineering (SMNE 2016) ISBN: 978-1-60595-338-0 A Visualization Scheme for Complex Spectrograms with Complete Amplitude and Phase Information Caixia Zheng School of Computer Science and Information Technology, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130117, China. School of Mathematics and Statistics, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, China. Guangyan Li School of Physics, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, China Tingfa Xu Photoelectric Imaging and Information Engineering Institute, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 100081, China Shili Liang School of Physics, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, China Xiaolin Cao College of Automotive Engineering, Jilin University, Changchun 130025, China Shuangwei Wang * School of Physics, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, China *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT: We present a novel visualization scheme for complex spectrograms of speech and other non-stationary signals, in which both the amplitude and phase information is visualized simultaneously using the conventional RGB (red, green, blue) color model. The three-layer image matrix is constructed in such a way that the absolute values of the real and imaginary parts of the time-frequency analysis of speech are used to fill the first (red) and third (blue) layers, respectively, and an encoding scheme is adopted to represent both signs of the real and imaginary parts and the computed values based on this encoding scheme are used to fill the second (green) layer. The importance of phase in spectrogram applications has been gradually recognized, and imaging processing techniques are increasingly used in spectral analysis of non-stationary one-dimensional (1D) signals such as speech signal. -

Prosody in the Production and Processing of L2 Spoken Language and Implications for Assessment

Teachers College, Columbia University Working Papers in TESOL & Applied Linguistics, 2014, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 1-20 Prosody in the Production and Processing of L2 Spoken Language and Implications for Assessment Prosody in the Production and Processing of L2 Spoken Language and Implications for Assessment Christos Theodoropulos1 Teachers College, Columbia University ABSTRACT This article offers an extended definition of prosody by examining the role of prosody in the production and comprehension of L2 spoken language from mainly a cognitive, interactionalist perspective. It reviews theoretical and empirical L1 and L2 research that have examined and explored the relationships between prosodic forms and their functions at the pragmatic and discourse levels. Finally, the importance and the various dimensions of these relationships in the context of L2 assessment are presented and the implications for L2 testing employing new technologies and automated scoring systems are discussed. INTRODUCTION More than two and a half decades ago, Major (1987), in one of the few articles in Language Testing to focus solely on the assessment of speaking in terms of phonological control, wrote that the "measurement of pronunciation accuracy [was] in the dark ages when compared to measurement of other areas of competence" (p. 155). Recognizing the potentially facilitative role of computer-assisted sound-analysis applications and software—a then relatively new industry— Major called for more investigative efforts into objective, reliable, valid, and viable measurements of second language (L2) pronunciation. Since then, only a relatively few noteworthy investigations have answered his call (e.g., Buck, 1989; Gorsuch, 2001; Isaacs, 2008; Koren, 1995; van Weeren & Theunissen, 1987; Yoshida, 2004). -

Speech Perception

18 Nov 2003 14:46 AR AR207-PS55-06.tex AR207-PS55-06.sgm LaTeX2e(2002/01/18) P1: GCE 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142028 Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004. 55:149–79 doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142028 Copyright c 2004 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved First published online as a Review in Advance on September 15, 2003 SPEECH PERCEPTION Randy L. Diehl Department of Psychology and Center for Perceptual Systems, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712-0187; email: [email protected] Andrew J. Lotto Boys Town National Research Hospital, Omaha, Nebraska 68131; email: [email protected] Lori L. Holt Department of Psychology and Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213; email: [email protected] Key Words auditory pattern recognition, categorical perception, phonetic context effects, perceptual learning, speech production ■ Abstract This chapter focuses on one of the first steps in comprehending spo- ken language: How do listeners extract the most fundamental linguistic elements— consonants and vowels, or the distinctive features which compose them—from the acoustic signal? We begin by describing three major theoretical perspectives on the perception of speech. Then we review several lines of research that are relevant to distinguishing these perspectives. The research topics surveyed include categorical perception, phonetic context effects, learning of speech and related nonspeech cate- gories, and the relation between speech perception and production. Finally, we describe challenges facing each of the major theoretical perspectives on speech perception. by University of Texas - Dallas on 09/10/12. For personal use only.