UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

Deictic Elements in Hyow and Kuki-Chin

Deictic Elements in Hyow and Kuki-Chin Kenneth P. Baclawski Jr Dartmouth College Program in Linguistics and Cognitive Science May 2012 1 1 Acknowledgements This thesis is indebted to the fieldwork and guidance of my advisor David A. Peterson, the dedicated work of Zakaria Rehman, and the cooperation of the Hyow people of Bangladesh. My second reader Timothy Pulju has also given invaluable feedback on earlier drafts of the manuscript. I would also like to thank Daniel Bruhn and James Matisoff at the Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus project at the University of California – Berkeley for their resources and kind support. The study is based in part on Hyow texts collected by Zakaria Rehman under NSF grant #BCS-0349021 to Dartmouth College (David A. Peterson, P.I.). My own research stems from earlier projects made possible by the James O. Freedman Presidential Scholars Program and the Leslie Embs Bradford 1977 and Charles C. Bradford Fund for Undergraduate Research. i Contents Abbreviations Used vi Introduction viii Chapter 1: Basic Phonology and Morphology of Hyow 1 1.1 Phonology 1 1.1.1 Consonant Phonemes 1 1.1.2 Vowel Phonemes 3 1.1.3 Diphthongs 4 1.2 The Hyow Syllable 5 1.2.1 The Syllable Canon 5 1.2.2 Tone 6 1.2.3 Sesquisyllabic Roots 7 1.3 The Phonological Word 8 1.4 Lexical Morphology 9 1.4.1 Noun Compounding 9 1.4.2 Verb Stem Formatives 10 1.4.3 Verb Stem Ablaut 12 1.5 Inflectional Morphology 14 1.5.1 Nominal Morphology 14 1.5.2 Verbal Morphology 15 1.6 Numerals 17 1.7 Verbal Participant Coding 18 1.7.1 Basic Paradigm -

China's Place in Philology: an Attempt to Show That the Languages of Europe and Asia Have a Common Origin

CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT Of CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF IB76 1918 Cornell University Library P 201.E23 China's place in phiiologyian attempt toI iPii 3 1924 023 345 758 CHmi'S PLACE m PHILOLOGY. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023345758 PLACE IN PHILOLOGY; AN ATTEMPT' TO SHOW THAT THE LANGUAGES OP EUROPE AND ASIA HAVE A COMMON OKIGIIS". BY JOSEPH EDKINS, B.A., of the London Missionary Society, Peking; Honorary Member of the Asiatic Societies of London and Shanghai, and of the Ethnological Society of France, LONDON: TRtJBNEE & CO., 8 aito 60, PATEENOSTER ROV. 1871. All rights reserved. ft WftSffVv PlOl "aitd the whole eaeth was op one langtta&e, and of ONE SPEECH."—Genesis xi. 1. "god hath made of one blood axl nations of men foe to dwell on all the face of the eaeth, and hath detee- MINED the ITMTIS BEFOEE APPOINTED, AND THE BOUNDS OP THEIS HABITATION." ^Acts Xvil. 26. *AW* & ju€V AiQionas fiereKlaOe tij\(J6* i6j/ras, AiOioiras, rol Si^^a SeSafarat effxarot av8p&Vf Ol fiiv ivffofievov Tireplovos, oi S' avdv-rof. Horn. Od. A. 22. TO THE DIRECTORS OF THE LONDON MISSIONAEY SOCIETY, IN EECOGNITION OP THE AID THEY HAVE RENDERED TO EELIGION AND USEFUL LEAENINO, BY THE RESEARCHES OP THEIR MISSIONARIES INTO THE LANGUAOES, PHILOSOPHY, CUSTOMS, AND RELIGIOUS BELIEFS, OP VARIOUS HEATHEN NATIONS, ESPECIALLY IN AFRICA, POLYNESIA, INDIA, AND CHINA, t THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. -

Himalayan Linguistics a Free Refereed Web Journal and Archive Devoted to the Study of the Languages of the Himalayas

himalayan linguistics A free refereed web journal and archive devoted to the study of the languages of the Himalayas Himalayan Linguistics Issues in Bahing orthography development Maureen Lee CNAS; SIL abstract Section 1 of this paper summarizes the community-based process of Bahing orthography development. Section 2 introduces the criteria used by the Bahing community members in deciding how Bahing sounds should be represented in the proposed Bahing orthography with Devanagari used as the script. This is followed by several sub-sections which present some of the issues involved in decision-making, the decisions made, and the rationale for these decisions for the proposed Bahing Devanagari orthography: Section 2.1 mentions the deletion of redundant Nepali Devanagari letters for the Bahing orthography; Section 2.2 discusses the introduction of new letters to represent Bahing sounds that do not exist in Nepali or are not distinctively represented in the Nepali Alphabet; Section 2.3 discusses the omission of certain dialectal Bahing sounds in the proposed Bahing orthography; and Section 2.4 discusses various length related issues. keywords Kiranti, Bahing language, Bahing orthography, orthography development, community-based orthography development This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 10(1) [Special Issue in Memory of Michael Noonan and David Watters]: 227–252. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2011. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/HimalayanLinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 10(1). © Himalayan Linguistics 2011 ISSN 1544-7502 Issues in Bahing orthography development Maureen Lee CNAS; SIL 1 Introduction 1.1 The Bahing language and speakers Bahing (Bayung) is a Tibeto-Burman Western Kirati language, with the traditional homelands of their speakers spanning the hilly terrains of the southern tip of Solumkhumbu District and the eastern part of Okhaldhunga District in eastern Nepal. -

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Diagnostic of Selected Sectors in Nepal

GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2020 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2020. ISBN 978-92-9262-424-8 (print); 978-92-9262-425-5 (electronic); 978-92-9262-426-2 (ebook) Publication Stock No. TCS200291-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS200291-2 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. -

Dimasa Kachari of Assam

ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY NO·7II , I \ I , CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME I MONOGRAPH SERIES PART V-B DIMASA KACHARI OF ASSAM , I' Investigation and Draft : Dr. p. D. Sharma Guidance : A. M. Kurup Editing : Dr. B. K. Roy Burman Deputy Registrar General, India OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS FOREWORD v PREFACE vii-viii I. Origin and History 1-3 II. Distribution and Population Trend 4 III. Physical Characteristics 5-6 IV. Family, Clan, Kinship and Other Analogous Divisions 7-8 V. Dwelling, Dress, Food, Ornaments and Other Material Objects distinctive qfthe Community 9-II VI. Environmental Sanitation, Hygienic Habits, Disease and Treatment 1~ VII. Language and Literacy 13 VIII. Economic Life 14-16 IX. Life Cycle 17-20 X. Religion . • 21-22 XI. Leisure, Recreation and Child Play 23 XII. Relation among different segments of the community 24 XIII. Inter-Community Relationship . 2S XIV Structure of Soci141 Control. Prestige and Leadership " 26 XV. Social Reform and Welfare 27 Bibliography 28 Appendix 29-30 Annexure 31-34 FOREWORD : fhe Constitution lays down that "the State shall promote with special care the- educational and economic hterest of the weaker sections of the people and in particular of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation". To assist States in fulfilling their responsibility in this regard, the 1961 Census provided a series of special tabulations of the social and economic data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are notified by the President under the Constitution and the Parliament is empowered to include in or exclude from the lists, any caste or tribe. -

Of Nepal UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council 23Rd Session

Annex-2 Words: 5482 Marginalized Groups' Joint Submission to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Nepal UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council 23rd Session Submitted by DURBAN REVIEW CONFERENCE FOLLOW-UP COMMITTEE (DRCFC) Jana Utthhan Pratisthan (JUP), Secretariat for the DRCFC, dedicated to promotion and protection of the Human Rights of Dalit. JUP has Special Consultative Status with United Nations Economic and Social Council 20th March 2015 Nepal I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY 1. This stakeholders' report is a joint submission of Durban Review Follow-up Committee (DRCFC), founded in 2009. DRCFC is a network working for protection and promotion of human rights of various marginalized groups of Nepal, namely: Dalit, Indigenous Peoples, Freed bonded laborers, Sexual and Gender minorities, Persons with Disability, Muslim and Religious minorities and Madhesis. 2. This report presents implementation status of UPR 2011 recommendations, and highlights major emerging themes of concerns regarding the human rights of the various vulnerable groups. This report is the outcome of an intensive consultation processes undertaken from October 2014 to January 2015 in regional and national basis. During this period, DRCFC conducted six regional consultations with the members of marginalized groups in five development regions and eight thematic and national consultation meetings at national level. In these consultations processes, nearly 682 representatives of 68 organizations attended and provided valuable information for this report (Annex-A). II. BACKGROUND AND FRAMEWORK 2.1. Scope of International Obligations 3. To ensure full compliance with international human rights standards, Nepal accepted recommendation (108:11)1 as a commitment to review and adopt relevant legislation and policies. -

Report on the 40 International Conference

This publication is supported by La Trobe University Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area http://www.latrobe.edu.au Volume 30.2 — October 2007 REPORT ON THE 40TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SINO-TIBETAN LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS (ICSTLL), HEILONGJIANG UNIVERSITY, SEPTEMBER 26-29, 2007 Jens Karlsson Lund University [email protected] In the far northeast of China, the mighty Songhua river, unusually devoid of water after an arid summer, ran partially shrouded in mist and rain, as the first of the 150 or so participants of the 40th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics arrived to the Ice City—Harbin, and Heilongjiang University—the venue for the conference of 2007.1 Chauffeurs and students constituting “components” of the “organisational apparatus”, headed by Prof. Dai Zhaoming, had a busy Tuesday meeting participants from nine different countries and regions, and shuttling them from the airport or train station to the conference venue, where registration and accommodation were managed. These tasks were, as far as I understand, carried out carefully, effectively and to the contentment of most participants. Mist and rain were driven off during the night, and a gentle autumn sun greeted us on Wednesday morning—the first day of the conference proper, and shone throughout most of the remainder of the conference, all in accordance with the “weather forecast” issued on the conference webpage months earlier! The Sun Forum of Heilongjiang University provided a thoroughly appropriate location for the opening ceremony with following keynote addresses, hosted by Prof. Sun Hongkai of the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and 1 The conference was jointly organised by the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Chinese Central University for Nationalities and Heilongjiang University. -

No Registration No Name Industry 1 10100003 RAI YOGENDRA

ममति २०७५ जेष्ठ २६ र २७ गि े मऱइएको नवौ कोररयन भाषा (EPS-TOPIK) परीऺामा सहभागी भएका तन륍न मऱखिि परीऺार्थीह셁 देहाय बमोजजम ऺेत्रका ऱागग उत्तिर्ण भएको ब्यहोरा HRD Korea बाट प्राप्ि भएकोऱे स륍बजधिि सबैको जानकारीको ऱागग यो सचना प्रकामिि गरीएको छ । उत्तिर्ण भएका ब्यजतिह셁को बबवरर् यस कायाणऱयको वेवसाइट , ू , , www.epsnepal.gov.np यस कायाणऱयको सूचनापाटी वैदेमिक रोजगार त्तवभागको वेभसाइट www.dofe.gov.np श्रम िर्था www.mole.gov.np HRD Korea www.eps.go.kr रोजगार मधत्राऱयको वेवसाइट र , को वेवसाइट बाट समेि हेन ण सककने छ । भाषा परीऺा उत्तिर्ण भएका ब्यजतिह셁को स्वास््य परीऺर् रोजगार आवेदन फाराम ऱगायिका कायहण 셁को बबस्ििृ त्तववरर् यस कायाणऱयको वेवसाइटमा तछटै प्रकामिि गररन े छ । भाषा परीऺा उत्तिर्ण ब्यजतिह셁ऱे रोजगार आवेदन फाराम(Job Application Form) भनकण ा ऱागग प्रहरी प्रतिवेदन िर्था स्वास््य परीऺर्मा समेि सफऱ हुन ु पन े छ। सार्थ ै कु न ै "क" बगकण ो बकℂ मा आफ्न ै नाममा िािा िोऱी सो को प्रमार् एव ं स륍बजधिि ब्यजतिको ब्यजतिगि ईमेऱ ठेगाना अतनवाय ण 셁पमा पेि गन ुण पन े ब्य ह ो र ा स म ेि स 륍 ब ज ध ि ि स ब ैक ो ज ा न क ार ी क ा ऱ ा ग ग य ो स ूच न ा प्र क ा म ि ि ग र ी ए क ो छ । पुनश्च: HRD Service of Korea को प्राप्ि पत्रानुसार यस पटकको Skill Test नहुन े ब्यहोरा समेि स륍बजधिि सबैको जानकारी गराईधछ । Registration No Name Industry No 1 10100003 RAI YOGENDRA Manufacturing > Assemble 2 10100010 KHATIWADA ROSHAN Manufacturing > Assemble 3 10100012 SHARMA PRADIP RAJ Agriculture and Farming of Animals > Livestocks 4 10100015 BADUWAL LALIT BAHADUR Manufacturing > Wood joinery 5 10100025 TAMANG MANISH Manufacturing > Assemble 6 10100032 RAI BHARATRAJ Manufacturing > Wood joinery -

Kh. Dhiren Singha Mob.: 09435173346 Associate Professor [email protected] Department of Linguistics, Dhiren [email protected] Assam University, Silchar

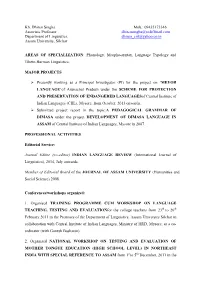

Kh. Dhiren Singha Mob.: 09435173346 Associate Professor [email protected] Department of Linguistics, [email protected] Assam University, Silchar AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION: Phonology, Morpho-syntax, Language Typology and Tibeto-Burman Linguistics. MAJOR PROJECTS Presently working as a Principal Investigator (PI) for the project on ‘MEYOR LANGUAGE’of Arunachal Pradesh under the SCHEME FOR PROTECTION AND PRESERVATION OF ENDANGERED LANGUAGESof Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL), Mysore, from October, 2013 onwards. Submitted project report in the topic:A PEDAGOGICAL GRAMMAR OF DIMASA under the project DEVELOPMENT OF DIMASA LANGUAGE IN ASSAM of Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore in 2007. PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES Editorial Service: Journal Editor (co-editor) INDIAN LANGUAGE REVIEW (International Journal of Linguistics), 2014, July onwards. Member of Editorial Board of the JOURNAL OF ASSAM UNIVERSITY (Humanities and Social Science) 2008. Conferences/workshops organized: 1. Organised TRAINING PROGRAMME CUM WORKSHOP ON LANGUAGE TEACHING, TESTING AND EVALUATIONfor the college teachers from 23rd to 26th February 2011 in the Premises of the Department of Linguistics, Assam University Silchar in collaboration with Central Institute of Indian Languages, Ministry of HRD, Mysore, as a co- ordinator (with Ganesh Baskaran). 2. Organised NATIONAL WORKSHOP ON TESTING AND EVALUATION OF MOTHER TONGUE EDUCATION (HIGH SCHOOL LEVEL) IN NORTHEAST INDIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO ASSAM from 1stto 5th December, 2011 in the Premises of the Department of Linguistics, Assam University Silchar in collaboration with Central Institute of Indian Languages, Ministry of HRD, Mysore, as a co-ordinator (with Ganesh Baskaran). PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS I. Life member of Dravidian Linguistics Association, St. Xavier’s College, P. O. -

Tone Systems of Dimasa and Rabha: a Phonetic and Phonological Study

TONE SYSTEMS OF DIMASA AND RABHA: A PHONETIC AND PHONOLOGICAL STUDY By PRIYANKOO SARMAH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Priyankoo Sarmah 2 To my parents and friends 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The hardships and challenges encountered while writing this dissertation and while being in the PhD program are no way unlike anything experienced by other Ph.D. earners. However, what matters at the end of the day is the set of people who made things easier for me in the four years of my life as a Ph.D. student. My sincere gratitude goes to my advisor, Dr. Caroline Wiltshire, without whom I would not have even dreamt of going to another grad school to do a Ph.D. She has been a great mentor to me. Working with her for the dissertation and for several projects broadened my intellectual horizon and all the drawbacks in me and my research are purely due my own markedness constraint, *INTELLECTUAL. I am grateful to my co-chair, Dr. Ratree Wayland. Her knowledge and sharpness made me see phonetics with a new perspective. Not much unlike the immortal Sherlock Holmes I could often hear her echo: One's ideas must be as broad as Nature if they are to interpret Nature. I am indebted to my committee member Dr. Andrea Pham for the time she spent closely reading my dissertation draft and then meticulously commenting on it. Another committee member, Dr. -

The Rhyme in Old Burmese Frederic Pain

Towards a panchronic perspective on a diachronic issue: the rhyme in Old Burmese Frederic Pain To cite this version: Frederic Pain. Towards a panchronic perspective on a diachronic issue: the rhyme in Old Burmese. 2014. hal-01009543 HAL Id: hal-01009543 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01009543 Preprint submitted on 18 Jun 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PRE-PRINT VERSION | 1 TOWARDS A PANCHRONIC PERSPECTIVE ON A DIACHRONIC ISSUE: THE RHYME <<----UIW>UIW> IN OLD BURMESE Pain Frederic Academia Sinica, Institute of Linguistics — Taipei Laboratoire Langues et Civilisations à Tradition Orale — Paris1 1.1.1. Theoretical background: PanchronPanchronyy and "Diahoric" StudiesStudies This paper aims at introducing to the panchronic perspective based on a specific problem of historical linguistics in Burmese. Its purpose is to demonstrate that a diachrony is not exclusively indicative of systemic internal contingencies but also a medium through which a socio-cultural situation of the past surfaces. In this sense, I will argue that both internal and external factors of a specific diachrony belong to both obverses of a same panchronic coin and that a combined analysis of both diachronic factors generates powerful explanatory models.