Evidence from Two Literary Prizes in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

View / Open Hirao Oregon 0171N 11721.Pdf

BINDING A UNIVERSE: THE FORMATION AND TRANSMUTATIONS OF THE BEST JAPANESE SF (NENKAN NIHON SF KESSAKUSEN) ANTHOLOGY SERIES by AKIKO HIRAO A THESIS Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2016 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Akiko Hirao Title: Binding a Universe: The Formation and Transmutations of the Best Japanese SF (Nenkan Nihon SF Kessakusen) Anthology Series This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Alisa Freedman Chairperson Glynne Walley Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2016. ii © 2016 Akiko Hirao This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Akiko Hirao Master of Arts Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures September 2016 Title: Binding a Universe: The Formation and Transmutations of the Best Japanese SF (Nenkan Nihon SF Kessakusen) Anthology Series The annual science fiction anthology series The Best Japanese SF started publication in 2009 and showcases domestic writers old and new and from a wide range of publishing backgrounds. Although representative of the second golden era of Japanese science fiction in print in its diversity and with an emphasis on that year in science fiction, as the volumes progress the editors’ unspoken agenda has become more pronounced, which is to create a set of expectations for the genre and to uphold writers Project Itoh and EnJoe Toh as exemplary of this current golden era. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

Inciting Difference and Distance in the Writings of Sakiyama Tami, Yi Yang-Ji, and Tawada Yōko

Inciting Difference and Distance in the Writings of Sakiyama Tami, Yi Yang-ji, and Tawada Yōko Victoria Young Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of East Asian Studies, School of Languages, Cultures and Societies March 2016 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2016 The University of Leeds and Victoria Young iii Acknowledgements The first three years of this degree were fully funded by a Postgraduate Studentship provided by the academic journal Japan Forum in conjunction with BAJS (British Association for Japanese Studies), and a University of Leeds Full Fees Bursary. My final year maintenance costs were provided by a GB Sasakawa Postgraduate Studentship and a BAJS John Crump Studentship. I would like to express my thanks to each of these funding bodies, and to the University of Leeds ‘Leeds for Life’ programme for helping to fund a trip to present my research in Japan in March 2012. I am incredibly thankful to many people who have supported me on the way to completing this thesis. The diversity offered within Dr Mark Morris’s literature lectures and his encouragement as the supervisor of my undergraduate dissertation in Cambridge were both fundamental factors in my decision to pursue further postgraduate studies, and I am indebted to Mark for introducing me to my MA supervisor, Dr Nicola Liscutin. -

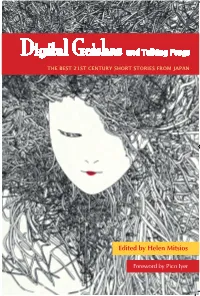

Digital Geishas Sample 4.Pdf

Literature/Asian Studies Digital Geishas Digital Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs With a foreword by Pico Iyer and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN This collection of short stories features the most up-to-date and exciting writing from the most popular and celebrated authors in Japan today. These wildly imaginative and boundary-bursting stories reveal fascinating and unexpected personal responses to the changes raging through today’s Japan. Along with some of the THE BEST 21 world’s most renowned Japanese authors, Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs includes many writers making their English-language debut. ST “Great stories rewire your brain, and in these tales you can feel your mind C E shifting as often as Mizue changes trains at the Shinagawa station in N T ‘My Slightly Crooked Brooch…’ The contemporary short stories in this URY SHO collection, at times subversive, astonishing and heart-rending, are brimming with originality and genius.” R —David Dalton, author of Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol T STO R “Here are stories that arrive from our global future, made from shards IES FR of many local, personal pasts. In the age of anime, amazingly, Japanese literature thrives.” O M JAPAN —Paul Anderer, Professor of Japanese, Columbia University About the Editor H EDITED BY Helen Mitsios is the editor of New Japanese Voices: The Best Contemporary Fiction from Japan, which was twice listed as a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She has recently co-authored the memoir Waltzing with the Enemy: A Mother and Daughter Confront the Aftermath of the Holocaust. -

Bungei Shunjū in the Early Years and the Emergence

THE EARLY YEARS OF BUNGEI SHUNJŪ AND THE EMERGENCE OF A MIDDLEBROW LITERATURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Minggang Li, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Richard Torrance, Adviser Professor William J. Tyler _____________________________ Adviser Professor Kirk Denton East Asian Languages and Literatures Graduate Program ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the complex relationship that existed between mass media and literature in pre-war Japan, a topic that is largely neglected by students of both literary and journalist studies. The object of this examination is Bungei shunjū (Literary Times), a literary magazine that played an important role in the formation of various cultural aspects of middle-class bourgeois life of pre-war Japan. This study treats the magazine as an organic unification of editorial strategies, creative and critical writings, readers’ contribution, and commercial management, and examines the process by which it interacted with literary schools, mainstream and marginal ideologies, its existing and potential readership, and the social environment at large. In so doing, this study reveals how the magazine collaborated with the construction of the myth of the “ideal middle-class reader” in the discourses on literature, modernity, and nation in Japan before and during the war. This study reads closely, as primary sources, the texts that were published in the issues of Bungei shunjū in the 1920s and 1930s. It then contrasts these texts with ii other texts published by the magazine’s peers and rivals. -

SO 008 492 Moddrn Japanese Novels.In English: a Selected Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 109 045 SO 008 492 AUTHOR Beauchamp, Nancy. Junko TITLE Moddrn Japanese Novels.in English: A Selected Bibliography. Service Cebter Paper on Asian Studies, No. 7. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Service Center for Teachers of Asian Studies. PUB DATE May 74 NOTE 44p. AIAILABLE FROM Dr. Franklin Buchanan, Association for Asian Studies, Ohio State University, 29 West Woodruff Avenue-, Columbus, Ohio 43210 ($1.00) 'EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC -$1.95 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; *Asian Studies; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; Humanities; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Literary Perspective; Literature Appreciation; *Literature Guides; Novels; Social Sciences; Social Studies; *Sociological Novels IDENTIFIERS *Japan IJ ABSTRACT Selected contemporary Japanese novels translated into English are compiled in this lbibliography as a guide for teachers interested in the possibilities offered by Japanese fiction. The bibliography acquaints teachers with available Japanese fiction, that can.be incorporated into social sciences or humanities courses to introduce Japan to students or to provide a comparative perspective. The selection, beginning with the first modern novel "Ukigumo," 1887-89, is limited to accessible full-length noyels with post-1945 translations, excluding short stories and fugitive works. The entries are arranged alphabetically by author, with his literary awards given first followed by an alphabetical listing of English titles of his works. The entry information for each title includes-the romanized Japanese title and original publication date, publications of the work, a short abstract, and major reviews. Included in the prefatory section are an overview of the milieu from which Japanese fiction has emerged; the scope of the contemporary period; and guides to new publications, abstracts, reviews, and criticisms and literary essays. -

Unbinding the Japanese Novel in English Translation

Department of Modern Languages Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki UNBINDING THE JAPANESE NOVEL IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION The Alfred A. Knopf Program, 1955 – 1977 Larry Walker ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in Auditorium XII University Main Building, on the 25th of September at 12 noon. Helsinki 2015 ISBN 978-951-51-1472-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-1473-0 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2015 ABSTRACT Japanese literature in English translation has a history of 165 years, but it was not until after the hostilities of World War II ceased that any single publisher outside Japan put out a sustained series of novel-length translations. The New York house of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. published thirty-four titles of Japanese literature in English translation in hardcover between the years 1955 to 1977. This “Program,” as it came to be called, was carried out under the leadership of Editor-in-Chief Harold Strauss (1907-1975), who endeavored to bring the then-active modern writers of Japan to the stage of world literature. Strauss and most of the translators who made this Program possible were trained in military language schools during World War II. The aim of this dissertation is to investigate the publisher’s policies and publishing criteria in the selection of texts, the actors involved in the mediation process and the preparation of the texts for market, the reception of the texts and their impact on the resulting translation profile of Japanese literature in America, England and elsewhere. -

Confronting ‟Unforeseen” Disasters: Yōko Tawada's Surrealist And

Author: Beaney, Tara Title: Confronting “Unforeseen” Disasters: Yokō Tawada’s Surrealist and Animistic Poetics Confronting ‟Unforeseen” Disasters: Yōko Tawada’s Surrealist and Animistic Poetics Tara Beaney University of Aberdeen [email protected] Abstract If our current environmental predicament, and recent catastrophes such as the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima in 2011, can be diagnosed as partly a crisis of the imagination, then radical action is needed. Ecopoetics can help by directing attention to the agentic properties of matter, and to the sometimes unexpected ways in which chains of events are brought about, through principles of both randomness and design. In Yō ko Tawada’s literary work, chance intra-actions between human and material agencies lead to a variety of surprising, surreal scenarios. Focusing on an array of Tawada’s texts, with particular attention to her post-Fukushima novel, The Last Children of Tokyo (US title The Emissary, 2018, Japanese original Kentōshi, 2014), this article argues that Tawada’s emphasis on the random and unexpected can provide a valuable ecopoetic perspective, serving both as political critique and as contribution to new materialist thought. Attention to material and linguistic agency is central to Tawada’s surrealist and animistic poetics, which foregrounds what she describes as ‟language magic”—language as an agentic force of its own with a propensity for generating unexpected effects. By situating Tawada’s post- Fukushima writing in the context of her wider work, I argue that her approach can help us to move to a less anthropocentric and agent-centric perspective through paying attention to the creative potential of language and matter, and to how these generate effects through processes of both randomness and design. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE EARLY FICTION OF MATSUMOTO SEICHO: DETECTIVE FICTION AS SOCIAL CRITIQUE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Michael S. Tangeman, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. William J. Tyler, Adviser Dr. Richard Torrance JcMl Dr. Mark Bender / Adviser department of East/Asian Languages and Literatures Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

How Junbungaku Affects the Akutagawa Prize and Japan's

EDITORS’ INTENTIONS AND AUTHORS’ DESIRES: HOW JUNBUNGAKU AFFECTS THE AKUTAGAWA PRIZE AND JAPAN’S COMMERCIAL LITERARY WORLD by Masumi Abe El-Khoury B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2011 © Masumi Abe El-Khoury, 2011 Abstract In this thesis I explore the current literary culture of Japan by examining the commercialization and politicization of junbungaku, “pure” literature. In particular, I focus on the most prominent award for new authors, the Akutagawa Prize, which is widely acknowledged as authoritative. My intention is to shed some useful light on the role of publishing company editors as the masterminds of the publishing industry. Chapter One provides an overview of issues surrounding junbungaku and taish! bungaku (“mass-oriented literature”). At present, junbungaku is defined in opposition to taish! bungaku, but ambiguities and boundary issues remain. This survey will enable us to identify the situations where the notion of junbungaku is defended as authoritative and how its relationship with the Akutagawa Prize increases its legitimacy. Chapter Two examines the origin and history of junbungaku, and discusses how the notion has changed over time. I also address questions such as what junbungaku is and how it can be defined, and uncover how junbungaku came under question as the Akutagawa Prize became more successful and began to overshadow junbungaku itself. The ultimate purpose of the Prize is to sell books and magazines; this affects not only literature but to some extent Japanese society as a whole.