Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Energy Board / Office National De L'énergie

National Energy Board / Office National de l'énergie 2013-12-16 - Application for Trans Mountain Expansion Project (OH-001-2014) / 2013-12-16 - Demande visant le projet d’agrandissement de Trans Mountain (OH-001-2014) C - Intervenors / C - Intervenants Filing Date / Exhibit number and Title / Titre et numéro de pièce Date de dépôt C001 - 16580-104th Ave (Owners) C1-0 - 16580-104th Ave (Owners) - Application To Participate (A58033) 02/11/2014 C1-0-1 - Application To Participate - A3U2T4 02/11/2014 C002 - Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) (changed from Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada) C249-1 - Government of Canada - Cover Letter and Information Request No. 1 to Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC (A60291) 05/12/2014 C249-2 - Natural Resources Canada - Letter of Clarification (A60393) 05/14/2014 C2-0 - Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada - Application To Participate (A58559) 02/12/2014 C2-0-1 - Application To Participate - A3U5G5 02/12/2014 C2-1 - Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada - Written Evidence of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development 05/26/2015 Canada (A70185) C2-1-1 - Written Evidence of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada - A4L5G9 05/26/2015 C2-2 - Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada - Affidavit (A71850) 08/14/2015 C2-2-1 - Affidavit - A4S2F8 08/14/2015 C003 - Adams Lake Indian Band C3-0 - ADAMS LAKE INDIAN BAND - Application To Participate (A56751) 01/30/2014 C3-0-1 - Application To Participate - A3T4I9 01/30/2014 C3-01 - Adams Lake Indian Band - Letter of Concern (A58964) 02/04/2014 C3-1-1 - Letter - A3U8G6 02/04/2014 C3-02 - Adams Lake Indian Band - ALIB Information Request No. -

10:30 AM Tsal'alh Elders Complex 600 Skiel Mountain Road, Shalalth, BC

Squamish-Lillooet Regional District Board Minutes June 28 and 29, 2017; 10:30 AM Tsal'alh Elders Complex 600 Skiel Mountain Road, Shalalth, BC In Attendance: Board: J. Crompton, Chair (Whistler); T. Rainbow, Vice-Chair (Area D); D. Demare (Area A); M. Macri (Area B); R. Mack (Area C); M. Lampman (Lillooet); P. Heintzman (Squamish) Absent: District of Squamish (One Director); Village of Pemberton Staff: L. Flynn, CAO (Deputy Corporate Officer); J. Nadon, Communications & Grant Coordinator Delegations: Tsal’alh Chief and Council; D. Wolfin, President & CEO, C. Daley, Corporate Social Responsibility Manager, Fred Sveinson, Senior Mining Advisor, Avino Silver & Gold Mines Ltd.; R. Joubert, General Manager, Tsal'alh Development Corporation; J. Coles, Area Manager, Bridge River Generation, J. Shepherd, Project Manager, M. DeHaan, Technical Principal, Planning & Water Licencing, J. Muir, Community Relations Regional Manager, R. Turner, Construction Manager, Lower Mainland, BC Hydro Others: P. Dahle (Area A - Alternate); D. DeYagher (Area B - Alternate); B. Baker of Britannia Oceanfront Development Corporation; members of the public 1. Call to Order The meeting was called to order at 10:30 AM. The Chair recognized that this meeting is being held on Tsal'alh Traditional Territory. In remembrance of Andrée Janyk 2. Approval of Agenda It was moved and seconded: THAT the following item be moved to immediately after Approval of Agenda: 7.3.2. Request for Decision - Britannia Oceanfront Developments Corporation - Rezoning and OCP Amendment Application Page 2 of 23 of the minutes of the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District Board meeting, held on Wednesday, June 28 and Thursday, June 29, 2017 in the Tsal'alh Elders Complex 600 Skiel Mountain Road, Shalalth, BC. -

COAST SALISH SENSES of PLACE: Dwelling, Meaning, Power, Property and Territory in the Coast Salish World

COAST SALISH SENSES OF PLACE: Dwelling, Meaning, Power, Property and Territory in the Coast Salish World by BRIAN DAVID THOM Department of Anthropology, McGill University, Montréal March, 2005 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Brian Thom, 2005 Abstract This study addresses the question of the nature of indigenous people's connection to the land, and the implications of this for articulating these connections in legal arenas where questions of Aboriginal title and land claims are at issue. The idea of 'place' is developed, based in a phenomenology of dwelling which takes profound attachments to home places as shaping and being shaped by ontological orientation and social organization. In this theory of the 'senses of place', the author emphasizes the relationships between meaning and power experienced and embodied in place, and the social systems of property and territory that forms indigenous land tenure systems. To explore this theoretical notion of senses of place, the study develops a detailed ethnography of a Coast Salish Aboriginal community on southeast Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Through this ethnography of dwelling, the ways in which places become richly imbued with meanings and how they shape social organization and generate social action are examined. Narratives with Coast Salish community members, set in a broad context of discussing land claims, provide context for understanding senses of place imbued with ancestors, myth, spirit, power, language, history, property, territory and boundaries. The author concludes in arguing that by attending to a theorized understanding of highly local senses of place, nuanced conceptions of indigenous relationships to land which appreciate indigenous relations to land in their own terms can be articulated. -

E. R. B UCKELL Dominion Entomological Laboratory, Kamloops, B

ENTOMOLOGICAL SOC. OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, PROC. (1949), VOL. 46, MAY 15, 1950 33 THE SOCIAL WASPS (VESPIDAE) OF BRITISH COLUMBIAl' E. R. B UCKELL Dominion Entomological Laboratory, Kamloops, B. C. AND G. J. SPENCER University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B. C. This paper on the social wasps of etts. for their determination. Frequent British Columbia has been prepared use has been made of Dr. Bequaert's from the collections in the Field Crop publications on the Vespidae (1931- Insect Laboratory, Kamloops, and the 1942), and many points of int,erest University of British Columbia, Van therein have been included in this paper. couver. The majority of the specimens were collected by the authors who are The localities from which material greatly indebted to Dr. J. Bequaert, has been recorded have been listed and Museum of Comparative Zoology, Har marked by a number on the accompany vard College, Cambridge, Massachus- ing map. Family VESPIDAE Vespa alascensis Packard, 1870, Trans. Chi cago Ac. Sci .• II. p. 27, PI. II. fig. 10 (I'; Subfamily VESPINAE (Lower Yukon, Alaska). Genus VESPULA C. G. Thomson Vespa westwoodii Shipp, 1893, Psyche, VI. The genus Vespula, with its two sub p. 450 (Boreal America). LOCALITIES - Vernon, Salmon Arm, Celista, genera, Vespula and Dolichovespula, in Squilax. Adams Lake, Chase, Kamloops, cludes the well known and pugnacious Douglas Lake, Minnie Lake, Bridge Lake, yellow-jackets and hornets. 100 Mile House, Canim Lake, Chilcotin, Alexandria, Quesnel. Barkerville, Prince The paper nests of yellow -jackets and George, Burns Lake, Yale, Skidegate. those of the large black and white, bald MATERIAL EXAMINED-24I' • 6 7 ~, 5 o. -

CURRICULUM VITAE for CARLSON, Keith Thor Canada Research Chair – Indigenous and Community-Engaged History University of the Fraser Valley

CURRICULUM VITAE for CARLSON, Keith Thor Canada Research Chair – Indigenous and Community-engaged History University of the Fraser Valley 1. PERSONAL: Born January 11, 1966. Powell River B.C., Canada. 2. DEGREES 2003. Ph.D, University of British Columbia, Aboriginal History. Dissertation title: The Power of Place, the Problem of Time: A Study of History and Aboriginal Collective Identity. (UBC Faculty of Arts nomination for Governor General’s Gold Medal; Honourable Mention for the Canadian Historical Association’s John Bullen Prize for best dissertation in history at a Canadian University). Supervisor: Professor Arthur J. Ray. 1992. M.A. University of Victoria, American Diplomatic History. Thesis title: The Twisted Road to Freedom: America’s Granting of Independence to the Philippines in 1946. (Co-op Education distinctions). Supervisor: Professor W.T. Wooley. 1988. B.A. University of Victoria, Double Major, History and Political Science. 3. CREDENTIALS 4. APPOINTMENTS AND PROMOTIONS 2020. Chair, Peace and Reconciliation Centre, University of the Fraser Valley 2019. Canada Research Chair, Tier I, Indigenous and Community Engaged History 2019. Professor of History, Tenured, University of the Fraser Valley 2015. University of Saskatchewan, Enhanced Centennial Research Chair in Indigenous and Community-Engaged History, UofS. Page 1 of 78 CARLSON, Keith Thor University of Saskatchewan 2012. Special Advisor on Outreach and Engagement to the Vice President Advancement, January 2012 – June 2013, UofS.. 2011. Director, Interdisciplinary Centre for Culture and Creativity, February 1, 2011 – July 31, 2014, UofS. 2010. Interim Director, Interdisciplinary Centre for Culture and Creativity, July 1, 2010, UofS. 2010. Promoted to Full Professor, UofS, July 1, 2010 2008 - 2011. -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov. -

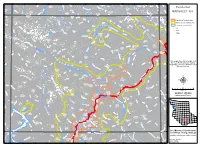

Pemberton MAPSHEET

124°0'0"W 123°30'0"W 123°0'0"W 122°30'0"W 122°0'0"W R p A R MTN K R MTN S O C S I T E R d L D M r u r R L I G W a t s o i A MT V E M r n C k m F C r r e e E a b McCLURE B l R T e y r e a C e Pemberton u D g h n k YALAKOM R t o C CHILKO MTN r O Warner e R E L x D I MTN M a O Lake N o V D N E CORNER r BIG SHEEP C u n R R G MTN R MAPSHEET 92J PEAK n I a PORTEAU C V pm E N N a r R HOGBACK " " C h MTN ELDORADO 0 0 ' ' MTN 0 0 MTN ° ° 1 1 5 5 MONMOUTH r COPPER C MTN k i c e t o n C r MTN L e Y e i L R C k A r s L e a e r r e t l d C A k e o K h R G Liza A N SHULAPS k M High Smoke Sensitivity Zone r M u c D L i u K R n c B PEAK a O S k L h e Tyaughton y l e o r L Medium Smoke Sensitivity Zone i SLOK l C r R m C e e I s V C r k E R M HILL a S C h u R r r l Low Smoke Sensitivity Zone e e s a I k h p t MT a s V S a l S l o n C l REX E k l SAWT A e R R ") y P PEAK City C E C r r N B e e MT Gun T MOHA e i r S e C C k s m E *# k SCHERLE L r h i B PENROSE R E Town t D o R h I PEAK I p D G E R R (! G l a c i e r I V E R B GOLD BRIDGE x L Village r A e a i K R c u E I R a l V BREXTON r E G R D O W N T O N MT T TOBA e TRUAX g L A K E PEAK i d r METSLAKA B KETA BRIDGE WHITE CROSS B PEAK Terzaghi R MTN I BRALORNE D MT Dam G L i l l E R E MT o o V Keary N e N t VAYU I " L " R R 0 C 0 ' TISIPHONE G r e ' 5 e k 5 l C 4 a 4 ° a ° c d 0 i l w 0 5 LILLOOET a 5 e l MT r a l p Silt l a c a SOUTH SHALALTH SHALALTH MTN W t e C d h i r McLEAN L a e r S r C Y WHITECAP S E MTN SETON PORTAGE E e k T MT e L r MT O C r C R N C McGILLIVRAY Lillooet r ATHELSTAN U r R r C e H e d L Seton l e A K E u E R L k E N o l L S T O K E A E B e R M C A B A e o B L O S e N c T t G T I a r i n SESSEL l C a SUGUS l MTN M GROUTY i MTN L v y r N T PEAK e N a O MT S o c k O l o e y r l B C y S r a A JOB P e t V L R h h a SIRENIA E i D MTN O FACE r This map is listed in Schedule 3 of N MTN A C r o n y R k t t e O B n l the Open Burning Smoke Control e C i I s w R e o r R E V r E o D V C I II C MT E L r k Regulation, under the Environmental R T R M e JOHN DECKER a g e r K C E r e N e D'ARCY Management Act. -

Nearshore Natural Capital Valuation Valuing the Aquatic Benefits of British Columbia’S Lower Mainland: Nearshore Natural Capital Valuation

VALUING THE AQUATIC BENEFITS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA’s LOWER MAINLAND Nearshore Natural Capital Valuation VALUING THE AQUatIC BENEFITS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA’S LOWER MAINLAND: NeaRSHORE NatURAL CAPItaL VALUatION November 2012 David Suzuki Foundation and Earth Economics By Michelle Molnar, Maya Kocian and David Batker AcknOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the extremely helpful contributions received during the preparation of this report. First and foremost, the authors wish to acknowledge the Sitka Foundation, who made this report possible. In addition, we would like to thank VanCity, Pacific Parklands, and Vancouver Foundation for their early and ongoing support of our natural capital work. We would like to thank Kelly Stewart (San Jose State University), Heidi Hudson (DSF), Zac Christin (EE), Lola Paulina Flores (EE) and David Marcell (EE) for their research assistance. Thanks to peer reviewers Sara Wilson (Natural Capital Research and Consulting), David Batker (EE), Jay Ritchlin (DSF) and Faisal Moola (DSF) for their advice, guidance and support in strengthening this report. Many thanks to Hugh Stimson (Geocology Research) who provided spatial data analysis and produced all of the maps within this report, and Scott Wallace (DSF) for sharing his fisheries data analysis. Copyedit and design by Nadene Rehnby handsonpublications.com Downloaded this report at davidsuzuki.org and eartheconomics.org Suite 219, 2211 West 4th Avenue 107 N. Tacoma Avenue Vancouver, B.C. V6K 4S2 Tacoma, WA 98403 T: 604.732.4228 T: 253.539.4801 E: [email protected] -

Hearing Order OH-001-2014 File No. OF-Fac-Oil-T260-2013-03 02 IN

Hearing Order OH-001-2014 File No. OF-Fac-Oil-T260-2013-03 02 IN THE MATTER OF TRANS MOUNTAIN PIPELINE ULC TRANS MOUNTAIN EXPANSION PROJECT FINAL WRITTEN ARGUMENT: INTERVENORS SWINOMISH INDIAN TRIBAL COMMUNITY, TULALIP TRIBES, SUQUAMISH TRIBE, AND LUMMI NATION (“U.S. TRIBES”) January 12, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 ARGUMENT ...................................................................................................................................2 I. THE U.S. TRIBES HAVE TREATY-RESERVED RIGHTS AND CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE SALISH SEA THAT ARE PUT AT RISK BY THE TRANSMOUNTAIN PROJECT. ........................................................................................2 A. U.S. Tribes Are Sovereign Nations That Retain Treaty Protected Fishing Areas In The Salish Sea. ..........................................................................................3 B. U.S. Tribal Commercial Fishing Practices Are Economically Significant. .............6 C. Tribal Fishing Is A Cultural, Ceremonial, and Subsistence Right. ..........................9 II. THE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT IS INCOMPLETE. ......................................11 A. TransMountain Failed To Consult With And Consider U.S. Tribal Interests. .................................................................................................................12 B. TransMountain Failed To Assess Impacts To U.S. Tribal Fishing Interests. ........13 -

The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau

The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau John Darwent Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University 1998 The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau By John Darwent Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University 1998 c. Archaeology Press 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, without prior written consent of the publisher. Printed and bound in Canada ISBN 0-86491-189-0 Publication No. 25 Archaeology Press Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6 (604)291-3135 Fax: (604) 291-5666 Editor: Roy L. Carlson Cover: Nephrite celts from near Lillooet, B.C. SFU Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Cat nos. 2750 and 2748 Table of Contents Acknowledgments v List of Tables vi List of Figures vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Types of Data 2 Ethnographic Information 2 Experimental Reconstruction 2 Context and Distribution 3 Artifact Observations 3 Analog Information 4 The Study Area . 4 Report Organization 4 2 Nephrite 6 Chemical and Physical Properties of Nephrite 6 Sources in the Pacific Northwest 6 Nephrite Sources in British Columbia 6 The Lillooet Segment 7 Omineca Segment 7 Cassiar Segment 7 Yukon and Alaska Nephrite Sources 8 Washington State and Oregon Nephrite Sources 8 Wyoming Nephrite Sources 9 Prehistoric Source Usage 9 Alternate Materials to Nephrite 10 Serpentine 10 Greenstone 10 Jadeite 10 Vesuvianite 10 3 Ethnographic and Archaeological Background of Nephrite Use 11 Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Study Area 11 Plateau Lifestyle 11 Cultural Complexity on the Plateau 11 Ethnographic Use of Nephrite . -

First Nations Water Rights in British Columbia

FIRSTNATIONS WATER RIGHTS IN BRITISHCOLUMBIA A Historical Summary of the rights of the Seton Lake First Nation _.-__ Management and Standards Branch Copy FIRST NATIONS WATER RIGHTS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA: A Historical Summary of the rights of the Seton Lake First Nation Research and writing by: Diana Jolly Edit by: JOL Consulting Review by: Gary W. Robinson Prepared for publication: December, 1999 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Jolly, Diana. First Nations water rights in British Columbia. A historical summary of the rights of the Seton Lake First Nation ISBN 0-7726-4057-2 1. Water rights - British Columbia - Mission Indian Reserve No. 5. 2. Water rights - British Columbia - Necait Indian Reserve No. 6. 3. Water rights - British Columbia - Silicon Indian Reserve No. 2. 4. Water rights - British Columbia - Slosh Indian Reserve No. 1. 5. Lillooet Indians - British Columbia - Government relations. I. JOL Consulting. 11. Robinson, Gary W. 111. British Columbia. Water Management Branch. IV. Title. V. Title: Historical summary of the rights of the Seton Lake First Nation. KEB529.5.W3J648 1999 346.71104'32 C99-960380-9 KF8210.W38J648 1999 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks wishes to acknowledge three partners whose contributions were invaluable in the completion of the Aboriginal Water Rights Report Series: 1. The Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs, was a critical source of funding, support and direction for this project. The U-Vic Geography Co-op Program, was instrumental in providing the staffing resources needed to undertake this challenging task. Through the . services of June Whitmore and her office, the project benefited from the research, writing, editing and co-ordination of these outstanding students: Jas Gill Christina Rocha Julie Steinhauer Rachel Abrams Kelly Babcock Elizabeth Lee Daniella Mops Sara Cheevers Miranda Griffith The services of Clover Point Cartographics Limited of Victoria, was responsible for the preparation of most of the map drawings, which form a valuable part of these documents. -

Bridge (Shalalth) – Seton (Lillooet) Capital Investment Update

Bridge (Shalalth) – Seton (Lillooet) Capital Investment Update June 2020 Agenda 1. Bridge River System Overview 2. Capital Plan Update (2019 – 2031) 3. Covid-19 Response 4. Workforce 5. Accommodation 6. Safety 7. Recreation Sites 8. Community Investment 9. Communications 2 Overview Bridge River System 3 Capital Plan Update Bridge River • Generating Station 1 o Units 1- 4 – planning currently underway, targeted completion in 2028 o Units 1- 4 Penstock Internal Recoating, planning currently underway, targeted Above: Bridge River 2 Unit 6 – Unit completed and completion in 2028 generating power • Generating Station 2: o Units 7&8 – pre-assembly work underway, targeted completion in 2021 o Concurrent Penstock Internal Recoating projects start this summer – targeted completion for both penstocks in 2021 Above: stator frame sits ready to be shipped to Bridge River 2 for work on Units 7&8. 4 Capital Plan Update La Joie Dam • La Joie Dam construction is targeted to begin in 2026 with targeted completion in 2031 • Currently reviewing schedule – still early stages • Construction will require low water levels in Downton Reservoir to enable the work 5 Capital Plan Update Seton Dam • Planning for Seton Generator Upgrade is currently underway, targeted completion in 2026 Dam Safety • Early planning stages for Surge Spill Hazard Mitigation project (Mission Mountain). Targeted completion in 2021. 6 Capital Plan Update Transmission • Transformer replacement work at Bridge River 1 and Bridge River Terminal, currently underway, targeted completion in 2020 and 2023, respectively Above and right: Crews install structures for the • Preliminary planning underway for 60L021 re-alignment transmission line work in the region, work between Lillooet and Shalalth targeted completion in 2025 completed in 2018.