The Burning Church at Shalalth: Two Eyewitness Accounts in St'át'imcets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10:30 AM Tsal'alh Elders Complex 600 Skiel Mountain Road, Shalalth, BC

Squamish-Lillooet Regional District Board Minutes June 28 and 29, 2017; 10:30 AM Tsal'alh Elders Complex 600 Skiel Mountain Road, Shalalth, BC In Attendance: Board: J. Crompton, Chair (Whistler); T. Rainbow, Vice-Chair (Area D); D. Demare (Area A); M. Macri (Area B); R. Mack (Area C); M. Lampman (Lillooet); P. Heintzman (Squamish) Absent: District of Squamish (One Director); Village of Pemberton Staff: L. Flynn, CAO (Deputy Corporate Officer); J. Nadon, Communications & Grant Coordinator Delegations: Tsal’alh Chief and Council; D. Wolfin, President & CEO, C. Daley, Corporate Social Responsibility Manager, Fred Sveinson, Senior Mining Advisor, Avino Silver & Gold Mines Ltd.; R. Joubert, General Manager, Tsal'alh Development Corporation; J. Coles, Area Manager, Bridge River Generation, J. Shepherd, Project Manager, M. DeHaan, Technical Principal, Planning & Water Licencing, J. Muir, Community Relations Regional Manager, R. Turner, Construction Manager, Lower Mainland, BC Hydro Others: P. Dahle (Area A - Alternate); D. DeYagher (Area B - Alternate); B. Baker of Britannia Oceanfront Development Corporation; members of the public 1. Call to Order The meeting was called to order at 10:30 AM. The Chair recognized that this meeting is being held on Tsal'alh Traditional Territory. In remembrance of Andrée Janyk 2. Approval of Agenda It was moved and seconded: THAT the following item be moved to immediately after Approval of Agenda: 7.3.2. Request for Decision - Britannia Oceanfront Developments Corporation - Rezoning and OCP Amendment Application Page 2 of 23 of the minutes of the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District Board meeting, held on Wednesday, June 28 and Thursday, June 29, 2017 in the Tsal'alh Elders Complex 600 Skiel Mountain Road, Shalalth, BC. -

E. R. B UCKELL Dominion Entomological Laboratory, Kamloops, B

ENTOMOLOGICAL SOC. OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, PROC. (1949), VOL. 46, MAY 15, 1950 33 THE SOCIAL WASPS (VESPIDAE) OF BRITISH COLUMBIAl' E. R. B UCKELL Dominion Entomological Laboratory, Kamloops, B. C. AND G. J. SPENCER University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B. C. This paper on the social wasps of etts. for their determination. Frequent British Columbia has been prepared use has been made of Dr. Bequaert's from the collections in the Field Crop publications on the Vespidae (1931- Insect Laboratory, Kamloops, and the 1942), and many points of int,erest University of British Columbia, Van therein have been included in this paper. couver. The majority of the specimens were collected by the authors who are The localities from which material greatly indebted to Dr. J. Bequaert, has been recorded have been listed and Museum of Comparative Zoology, Har marked by a number on the accompany vard College, Cambridge, Massachus- ing map. Family VESPIDAE Vespa alascensis Packard, 1870, Trans. Chi cago Ac. Sci .• II. p. 27, PI. II. fig. 10 (I'; Subfamily VESPINAE (Lower Yukon, Alaska). Genus VESPULA C. G. Thomson Vespa westwoodii Shipp, 1893, Psyche, VI. The genus Vespula, with its two sub p. 450 (Boreal America). LOCALITIES - Vernon, Salmon Arm, Celista, genera, Vespula and Dolichovespula, in Squilax. Adams Lake, Chase, Kamloops, cludes the well known and pugnacious Douglas Lake, Minnie Lake, Bridge Lake, yellow-jackets and hornets. 100 Mile House, Canim Lake, Chilcotin, Alexandria, Quesnel. Barkerville, Prince The paper nests of yellow -jackets and George, Burns Lake, Yale, Skidegate. those of the large black and white, bald MATERIAL EXAMINED-24I' • 6 7 ~, 5 o. -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov. -

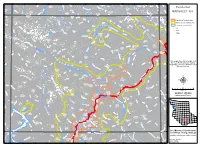

Pemberton MAPSHEET

124°0'0"W 123°30'0"W 123°0'0"W 122°30'0"W 122°0'0"W R p A R MTN K R MTN S O C S I T E R d L D M r u r R L I G W a t s o i A MT V E M r n C k m F C r r e e E a b McCLURE B l R T e y r e a C e Pemberton u D g h n k YALAKOM R t o C CHILKO MTN r O Warner e R E L x D I MTN M a O Lake N o V D N E CORNER r BIG SHEEP C u n R R G MTN R MAPSHEET 92J PEAK n I a PORTEAU C V pm E N N a r R HOGBACK " " C h MTN ELDORADO 0 0 ' ' MTN 0 0 MTN ° ° 1 1 5 5 MONMOUTH r COPPER C MTN k i c e t o n C r MTN L e Y e i L R C k A r s L e a e r r e t l d C A k e o K h R G Liza A N SHULAPS k M High Smoke Sensitivity Zone r M u c D L i u K R n c B PEAK a O S k L h e Tyaughton y l e o r L Medium Smoke Sensitivity Zone i SLOK l C r R m C e e I s V C r k E R M HILL a S C h u R r r l Low Smoke Sensitivity Zone e e s a I k h p t MT a s V S a l S l o n C l REX E k l SAWT A e R R ") y P PEAK City C E C r r N B e e MT Gun T MOHA e i r S e C C k s m E *# k SCHERLE L r h i B PENROSE R E Town t D o R h I PEAK I p D G E R R (! G l a c i e r I V E R B GOLD BRIDGE x L Village r A e a i K R c u E I R a l V BREXTON r E G R D O W N T O N MT T TOBA e TRUAX g L A K E PEAK i d r METSLAKA B KETA BRIDGE WHITE CROSS B PEAK Terzaghi R MTN I BRALORNE D MT Dam G L i l l E R E MT o o V Keary N e N t VAYU I " L " R R 0 C 0 ' TISIPHONE G r e ' 5 e k 5 l C 4 a 4 ° a ° c d 0 i l w 0 5 LILLOOET a 5 e l MT r a l p Silt l a c a SOUTH SHALALTH SHALALTH MTN W t e C d h i r McLEAN L a e r S r C Y WHITECAP S E MTN SETON PORTAGE E e k T MT e L r MT O C r C R N C McGILLIVRAY Lillooet r ATHELSTAN U r R r C e H e d L Seton l e A K E u E R L k E N o l L S T O K E A E B e R M C A B A e o B L O S e N c T t G T I a r i n SESSEL l C a SUGUS l MTN M GROUTY i MTN L v y r N T PEAK e N a O MT S o c k O l o e y r l B C y S r a A JOB P e t V L R h h a SIRENIA E i D MTN O FACE r This map is listed in Schedule 3 of N MTN A C r o n y R k t t e O B n l the Open Burning Smoke Control e C i I s w R e o r R E V r E o D V C I II C MT E L r k Regulation, under the Environmental R T R M e JOHN DECKER a g e r K C E r e N e D'ARCY Management Act. -

The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau

The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau John Darwent Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University 1998 The Prehistoric Use of Nephrite on the British Columbia Plateau By John Darwent Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University 1998 c. Archaeology Press 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, without prior written consent of the publisher. Printed and bound in Canada ISBN 0-86491-189-0 Publication No. 25 Archaeology Press Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6 (604)291-3135 Fax: (604) 291-5666 Editor: Roy L. Carlson Cover: Nephrite celts from near Lillooet, B.C. SFU Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Cat nos. 2750 and 2748 Table of Contents Acknowledgments v List of Tables vi List of Figures vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Types of Data 2 Ethnographic Information 2 Experimental Reconstruction 2 Context and Distribution 3 Artifact Observations 3 Analog Information 4 The Study Area . 4 Report Organization 4 2 Nephrite 6 Chemical and Physical Properties of Nephrite 6 Sources in the Pacific Northwest 6 Nephrite Sources in British Columbia 6 The Lillooet Segment 7 Omineca Segment 7 Cassiar Segment 7 Yukon and Alaska Nephrite Sources 8 Washington State and Oregon Nephrite Sources 8 Wyoming Nephrite Sources 9 Prehistoric Source Usage 9 Alternate Materials to Nephrite 10 Serpentine 10 Greenstone 10 Jadeite 10 Vesuvianite 10 3 Ethnographic and Archaeological Background of Nephrite Use 11 Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Study Area 11 Plateau Lifestyle 11 Cultural Complexity on the Plateau 11 Ethnographic Use of Nephrite . -

First Nations Water Rights in British Columbia

FIRSTNATIONS WATER RIGHTS IN BRITISHCOLUMBIA A Historical Summary of the rights of the Seton Lake First Nation _.-__ Management and Standards Branch Copy FIRST NATIONS WATER RIGHTS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA: A Historical Summary of the rights of the Seton Lake First Nation Research and writing by: Diana Jolly Edit by: JOL Consulting Review by: Gary W. Robinson Prepared for publication: December, 1999 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Jolly, Diana. First Nations water rights in British Columbia. A historical summary of the rights of the Seton Lake First Nation ISBN 0-7726-4057-2 1. Water rights - British Columbia - Mission Indian Reserve No. 5. 2. Water rights - British Columbia - Necait Indian Reserve No. 6. 3. Water rights - British Columbia - Silicon Indian Reserve No. 2. 4. Water rights - British Columbia - Slosh Indian Reserve No. 1. 5. Lillooet Indians - British Columbia - Government relations. I. JOL Consulting. 11. Robinson, Gary W. 111. British Columbia. Water Management Branch. IV. Title. V. Title: Historical summary of the rights of the Seton Lake First Nation. KEB529.5.W3J648 1999 346.71104'32 C99-960380-9 KF8210.W38J648 1999 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks wishes to acknowledge three partners whose contributions were invaluable in the completion of the Aboriginal Water Rights Report Series: 1. The Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs, was a critical source of funding, support and direction for this project. The U-Vic Geography Co-op Program, was instrumental in providing the staffing resources needed to undertake this challenging task. Through the . services of June Whitmore and her office, the project benefited from the research, writing, editing and co-ordination of these outstanding students: Jas Gill Christina Rocha Julie Steinhauer Rachel Abrams Kelly Babcock Elizabeth Lee Daniella Mops Sara Cheevers Miranda Griffith The services of Clover Point Cartographics Limited of Victoria, was responsible for the preparation of most of the map drawings, which form a valuable part of these documents. -

Bridge (Shalalth) – Seton (Lillooet) Capital Investment Update

Bridge (Shalalth) – Seton (Lillooet) Capital Investment Update June 2020 Agenda 1. Bridge River System Overview 2. Capital Plan Update (2019 – 2031) 3. Covid-19 Response 4. Workforce 5. Accommodation 6. Safety 7. Recreation Sites 8. Community Investment 9. Communications 2 Overview Bridge River System 3 Capital Plan Update Bridge River • Generating Station 1 o Units 1- 4 – planning currently underway, targeted completion in 2028 o Units 1- 4 Penstock Internal Recoating, planning currently underway, targeted Above: Bridge River 2 Unit 6 – Unit completed and completion in 2028 generating power • Generating Station 2: o Units 7&8 – pre-assembly work underway, targeted completion in 2021 o Concurrent Penstock Internal Recoating projects start this summer – targeted completion for both penstocks in 2021 Above: stator frame sits ready to be shipped to Bridge River 2 for work on Units 7&8. 4 Capital Plan Update La Joie Dam • La Joie Dam construction is targeted to begin in 2026 with targeted completion in 2031 • Currently reviewing schedule – still early stages • Construction will require low water levels in Downton Reservoir to enable the work 5 Capital Plan Update Seton Dam • Planning for Seton Generator Upgrade is currently underway, targeted completion in 2026 Dam Safety • Early planning stages for Surge Spill Hazard Mitigation project (Mission Mountain). Targeted completion in 2021. 6 Capital Plan Update Transmission • Transformer replacement work at Bridge River 1 and Bridge River Terminal, currently underway, targeted completion in 2020 and 2023, respectively Above and right: Crews install structures for the • Preliminary planning underway for 60L021 re-alignment transmission line work in the region, work between Lillooet and Shalalth targeted completion in 2025 completed in 2018. -

Cayoosh Mountains

Vol.31 No.1 Winter 2012 Published by the Wilderness Committee FREE REPORT BENDOR AND CAYOOSH MOUNTAINS TRIBAL PARK PROTECTION NEEDED NOW! BEAUTIFUL LANDS OF THE ST'ÁT'IMC Joe Foy National Campaign Portage, Shalalth, Samahquam, Skatin which means they have pockets of both proposed tribal parks encompassing Director, and Douglas are strategically located on types of habitat. Unfortunately both the Bendor and Cayoosh mountains. Wilderness Committee trail and canoe routes that are thousands ranges are under threat from proposed This is an important step forward of years old near some of the world's industrial developments including that needs to be taken, and one most productive wild salmon rivers.1 logging and a proposed ski resort. So that is long overdue. Read on to Within St'át'imc territory are some of far the rugged nature of the Bendor and learn how you can help gain tribal here do I go when I want my favourite protected areas, including Cayoosh mountains and the courageous park protection for the Bendor and Wto see some of the wildest, portions of Garibaldi Provincial Park, nature of the St'át'imc people have Cayoosh mountains! most beautiful landscapes in the Stein Valley Nlaka'pamux Heritage been able to fend off the worst of the world? Where do I go when I want to Park and South Chilcotin Mountains industrial projects, which is why these Learn about the experience a place and a culture where Provincial Park. areas are still so wild and beautiful. But St'át'imc people people have lived for centuries upon However, two wilderness mountain for how long? centuries? I go to St'át'imc of course! ranges located in the heart of St'át'imc The St'át'imc have produced a land- and their land Several hundred kilometres to territory that are critical to the region's use plan for the northern portion of at statimc.net the north of Vancouver, BC lies the ecological and cultural well-being are their territory. -

Enhanced Economic Direction for the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District a Discussion Paper

Enhanced Economic Direction for the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District A Discussion Paper October 2001 Squamish-Lillooet Regional District Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 2 SLRD Mission and Shared Values 2 Geographical and Natural Environment Setting 3 Demographics Summary 3 Snapshot of the Region’s Economy 5 Provincial Context: BC Current Economic Trends 5 Regional Economic Indicators 5 Forestry 7 Tourism 8 Agriculture 9 Transportation 9 Regional Economic Issues 10 Emerging and Future Regional Economic Opportunities 11 Economic Opportunities and Sustainability 12 Recommendations for Action 13 Statement of Regional Priorities & Resource Requirements 14 Appendix "A": References 19 Appendix “B” Workshop Participants 20 Appendix "C" Lillehammer 1994 Olympic Economic Planning 21 Appendix "D" Salt Lake City 2002 Olympic Economic Planning 26 Appendix “E” Fraser Basin Council’s Charter for Sustainability Enhanced Economic Direction for the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District October 2001 Discussion Paper Executive Summary The Squamish-Lillooet Regional District (SLRD) Board of Directors wishes to ensure that investments in the Squamish-Lillooet Region contribute to its long-term economic sustainability. The Fraser Basin Council was asked by the SLRD to work with its Board of Directors to develop this discussion paper in order to convey, to the Provincial 2010 Olympic Bid Secretariat and others, the SLRD Board’s consensus on key investment priorities. The Board believes that there is a strong rationale in any case to address these priorities, given the outstanding assets the Region has to offer and the importance of the Region to the provincial economy. The Olympic bid is viewed by the Board as an excellent opportunity to address the priorities sooner and in a way that augments the prospects for a successful bid. -

British Columbia Postal History Newsletter

ARCH GR SE OU E P BRITISH COLUMBIA R POST OFFICE B POSTAL HISTORY R I A IT B ISH COLUM NEWSLETTER Volume 24 Number 1 Whole number 93 March 2015 A registered cover from the Minto General Store to Vancouver, dated Apr 1, 1941. Backstamps are Shalalth (Apr 2 duplex), Vancouver (Apr 2 CDS) and Vancouver Postal Station K (Apr 3 CDS). This issue’s Favourite Cover is from Minto Mine, group of residents: 25 Japanese-Canadian families, located on the Bridge River, northwest of Lillooet considered enemy aliens and forcibly relocated from and about 200 km north of Vancouver. Minto was a the BC coast until after the end of WWII. promising 1930s gold discovery. A townsite, usually In 1960, when the last residents left, Minto Mine post known as Minto or Minto City, was established office closed (June 17). That year the Bridge River nearby in 1934 and soon boasted 300 residents. A post was dammed as part of a gigantic hydroelectric office opened on Jan 1, 1935. project to provide power to Vancouver. Minto City, While nearby Bralorne and Pioneer mines proved along with its neighbouring hamlets of Wayside to have plenty of reserves of ore, the gold at Minto and Congress, disappeared beneath the waters of was soon played out. By 1938 the mine had failed. In Carpenter Lake, a new artificial reservoir. At extreme 1942, however, Minto’s status as an isolated, interior low water, apparently, the outline of the townsite is ghost town made it the perfect destination for a new still visible.—Andrew Scott In this issue: • Favourite cover: Minto General Store p 847 • The John Woolsey correspondence p 852 • Important information for subscribers p 848 • Remembering Janes Road post office p 856 • Straightline handstamp update p 849 • Victoria cork cancel survey, Part I p 857 • Gibsons to Brazil for MS Gripsholm p 850 • New post office markings at Sechelt p 862 BC Postal History Newsletter #93 Page 848 Editorial Alex was a consummate postal historian. -

Download The

Indigenous Perspectives on the Outstanding Land Issue in British Columbia: “We deny their right to it” by Cathrena Narcisse B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1994 M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1998 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2016 © Cathrena Narcisse, 2016 Abstract Arising from and sustained within the context of colonialism, the outstanding indigenous land issue in British Columbia has long been a source of significant conflict between indigenous people and settler governments. Due to its significantly complex political and legal background, it is difficult to reach a clear and comprehensive understanding about this matter, and gaining insight into the indigenous perspective about it is even more challenging. Explicitly considering the broader framework of colonialism in exploring the outstanding indigenous land issue in British Columbia, this dissertation places its focus upon detailing the indigenous perspective in relation to opposing political and legal government positions. Such a study is important in order to adequately understand the perpetuation of the conflicts between indigenous peoples and governments over the outstanding land issue. The research approach relies upon the examination of archival data, along with representations of indigenous oral history narratives, and attendance at indigenous political gatherings. In particular, this research project relies upon information gathered from both indigenous elders and political representatives through interviews and political meetings to form the basis of indigenous perspectives on the outstanding land issue. The findings from this research provide evidence that a discernible pattern of denial and disregard has been established and maintained by successive settler governments and that these patterns are purposefully perpetuated. -

The Kaoham Shuttle

Views & Vistas The Kaoham Shuttle Site #040302 GC1VKHP Written & Researched by Wendy Fraser Site identification Nearest Community: Lillooet, V0K 1V0 Train Station: N 50°41.099’ W 121°56.166’ Geocache Location: N 50°43.759’ W 122°13.193’ Accuracy: 5 meters Letterboxing Clues: Refer to letterboxing clues page UTM: East 0555058; North 5620015 10U Geocache altitude: 262 m./861 ft. Overall difficulty: 1 Terrain difficulty: 1.5 (1=easiest; 5=hardest) Date Established: 1915 Ownership: C.N. Rail & First Nations Access: • Public Road • Year-round All aboard the Kaoham Shuttle! • Vehicle accessibl escribed as one of the most allow photographers to capture • Detailed access spectacular rail trips in the those special glimpses of the local information on next D world, this ‘Little Engine That wildlife. page. Could’ first travels from Lillooet through the narrow Seton River The Kaoham Shuttle links Lillooet canyon. It then proceeds along with the remote lakeside the scenic northwest shoreline communities of Seton Portage of 24.3 kilometre-long Seton and Shalalth. The shuttle is an Lake, a long, fjord-like finger of economical and green alternative glacial jade-green water. The lake to the only other link between is walled in by near-vertical cliffs Lillooet and Seton Portage or and towering mountains soaring Shalalth, a steep gravel road over to heights of over 2,000 metres. Mission Mountain that concludes Bighorn sheep, bears, deer and with a dramatic 1,300 metre eagles are often seen along the descent to Seton Lake. For more information or to report a problem route and the train will stop to with this site please contact: Gold Country Communities Society P.O.