Language of Instruction Country Profile Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surrogate Surfaces: a Contextual Interpretive Approach to the Rock Art of Uganda

SURROGATE SURFACES: A CONTEXTUAL INTERPRETIVE APPROACH TO THE ROCK ART OF UGANDA by Catherine Namono The Rock Art Research Institute Department of Archaeology School of Geography, Archaeology & Environmental Studies University of the Witwatersrand A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 i ii Declaration I declare that this is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. Signed:……………………………….. Catherine Namono 5th March 2010 iii Dedication To the memory of my beloved mother, Joyce Lucy Epaku Wambwa To my beloved father and friend, Engineer Martin Wangutusi Wambwa To my twin, Phillip Mukhwana Wambwa and Dear sisters and brothers, nieces and nephews iv Acknowledgements There are so many things to be thankful for and so many people to give gratitude to that I will not forget them, but only mention a few. First and foremost, I am grateful to my mentor and supervisor, Associate Professor Benjamin Smith who has had an immense impact on my academic evolution, for guidance on previous drafts and for the insightful discussions that helped direct this study. Smith‘s previous intellectual contribution has been one of the corner stones around which this thesis was built. I extend deep gratitude to Professor David Lewis-Williams for his constant encouragement, the many discussions and comments on parts of this study. His invaluable contribution helped ideas to ferment. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Newsletter March 2021

NewsLetter March 2021 Celebrating 50th AGM Bible Society of Kenya held her 50th transformed formed through the work National Annual General Meeting on of BSK. Looking back, we have a lot to March 27th virtually on zoom. thank God for. This was a special meeting as the The event was graced by members from society marked its 50th AGM. We thank different branches including; Machakos, God for his goodness as we celebrate Bungoma, Kericho, Nairobi, Kakamega, our heritage throughout all these years Kisumu, Meru, Nakuru, Kiambu and and for the lives that have been Nyeri who turned up to attend the event. AGM Screen shot General Secretary Mrs. Muriuki cuts a cake to - 1 - commemorate the 50th AGM celebrations. The National Annual General Meeting is an annual Kisau welcomed the new Council » Equipped future church leaders in forum for BSK registered members where they come to members noting that they will steer theological colleges / universities interact, receive reports of performance for the previous the ministry of BSK to greater with Scholarly Scriptures. year, elect new Board members and get projections on heights. He added that as more » Served the visually impaired through the upcoming plans for the year. Christians join the lively team of Braille Bible distribution members, they will collectively The Guest speaker for the day was Mrs. Jemima Chiruyi impact the community positively In March 2021, various branches from International Christian Center. She spoke on this through God’s word. held their AGMs before the main year’s theme “Be still and know that I am God” from AGM. -

Monolingualism Via Multilingualism: a Case Study of Language Use in the West Ugandan Town of Hoima

African Study Monographs, 34 (1): 1–25, March 2013 1 MONOLINGUALISM VIA MULTILINGUALISM: A CASE STUDY OF LANGUAGE USE IN THE WEST UGANDAN TOWN OF HOIMA Shigeki KAJI Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Multilingualism is one of the most salient features of language use in Africa and, at first sight, Uganda appears to be just one example of this practice. However, as Uganda has no lingua franca that is widely used by its entire population, questions about how people cope with multilingualism arise. Answers to such questions can be found in the fact that people are able to create a monolingual state in a given area because everyone is multilingual. That is, people speak their own language in their own domain and speak other peoples’ languages when they go to the latter’s domains. This conclusion emerged from interviews conducted with 100 inhabitants of Hoima city in western Uganda, an area primarily inhabited by the Nyoro people. The linguistic situation in Hoima provides a valuable case study of what can happen in the absence of a fully developed lingua franca and can contribute to broader discussions of language use in Africa. Key Words: Lingua franca; Multilingualism; Hoima; Nyoro; Uganda. INTRODUCTION I have conducted linguistic research in Uganda since 2001. The main themes of my research relate to the grammatical and lexical characteristics of little-known languages in the area. In the course of research, however, I noticed differences between the use of language in Uganda and that in the regions where I had studied before. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) K-TEA (Achievement test) Kʻa-la-kʻun-lun kung lu (China and Pakistan) USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Karakoram Highway (China and Pakistan) K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) K-theory Ka Lae o Kilauea (Hawaii) USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) [QA612.33] USE Kilauea Point (Hawaii) K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) BT Algebraic topology Ka Lang (Vietnamese people) UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) Homology theory USE Giẻ Triêng (Vietnamese people) K9 (Fictitious character) NT Whitehead groups Ka nanʻʺ (Burmese people) (May Subd Geog) K 37 (Military aircraft) K. Tzetnik Award in Holocaust Literature [DS528.2.K2] USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) UF Ka-Tzetnik Award UF Ka tūʺ (Burmese people) K 98 k (Rifle) Peras Ḳ. Tseṭniḳ BT Ethnology—Burma USE Mauser K98k rifle Peras Ḳatseṭniḳ ʾKa nao dialect (May Subd Geog) K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 BT Literary prizes—Israel BT China—Languages USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 K2 (Pakistan : Mountain) Hmong language K.A. Lind Honorary Award UF Dapsang (Pakistan) Ka nō (Burmese people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris Godwin Austen, Mount (Pakistan) USE Tha noʹ (Burmese people) K.A. Linds hederspris Gogir Feng (Pakistan) Ka Rang (Southeast Asian people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris Mount Godwin Austen (Pakistan) USE Sedang (Southeast Asian people) K-ABC (Intelligence test) BT Mountains—Pakistan Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere (N.Z.) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children Karakoram Range USE Franz Josef Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine K-B Bridge (Palau) K2 (Drug) Hukatere (N.Z.) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Synthetic marijuana Ka-taw K-BIT (Intelligence test) K3 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE Takraw USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test USE Broad Peak (Pakistan and China) Ka Tawng Luang (Southeast Asian people) K. -

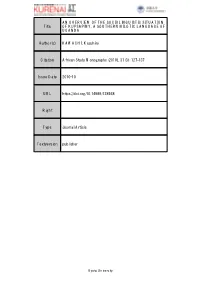

Title an OVERVIEW of the SOCIOLINGUISTIC SITUATION OF

AN OVERVIEW OF THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC SITUATION Title OF KUPSAPINY, A SOUTHERN NILOTIC LANGUAGE OF UGANDA Author(s) KAWACHI, Kazuhiro Citation African Study Monographs (2010), 31(3): 127-137 Issue Date 2010-10 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/128938 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 31(3): 127-137, October 2010 127 AN OVERVIEW OF THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC SITUATION OF KUPSAPINY, A SOUTHERN NILOTIC LANGUAGE OF UGANDA Kazuhiro KAWACHI Department of Foreign Languages, School of Liberal Arts and General Education, National Defense Academy of Japan ABSTRACT This study reports on the sociolinguistic situation of Kupsapiny, the Southern Nilotic language spoken by the Sebei people in the Sebei region of Uganda. Even though the Sebei are highly conservative in various respects, Kupsapiny has been losing its vitality. Primarily because the history of the people has been adverse to the maintenance of their language, it has undergone considerable change under the infl uence of English, Swahili, and Lugisu (Bantu). In order to revitalize Kupsapiny, its use in schools, which is currently limited to grade one through grade four in public schools, should be extended through primary education at least. Prior to this, however, the language needs to develop a written system. Key Words: Kupsapiny (Sebei, Sapiny); Southern Nilotic; Uganda; Language revitalization; Community profi le. INTRODUCTION The objectives of this study are (i) to write a community profi le of the Sebei region of Uganda, where Kupsapiny (Southern Nilotic) is spoken, (ii) to report on the diminishing vitality of this language, and (iii) to point out possible ways to revitalize this language.(1) This study is based primarily on interviews I conducted with native speakers of the language during my fi eldwork in Kapchorwa from July 11 through August 1, 2009 and from July 30 through August 27, 2010. -

LCSH Section U

U-2 (Reconnaissance aircraft) (Not Subd Geog) U.S. 29 U.S. Bank Stadium (Minneapolis, Minn.) [TL686.L (Manufacture)] USE United States Highway 29 BT Stadiums—Minnesota [UG1242.R4 (Military aeronautics)] U.S. 30 U.S. Bicycle Route System (May Subd Geog) UF Lockheed U-2 (Airplane) USE United States Highway 30 UF USBRS (U.S. Bicycle Route System) BT Lockheed aircraft U.S. 31 BT Bicycle trails—United States Reconnaissance aircraft USE United States Highway 31 U.S.-Canada Border Region U-2 (Training plane) U.S. 40 USE Canadian-American Border Region USE Polikarpov U-2 (Training plane) USE United States Highway 40 U.S. Capitol (Washington, D.C.) U-2 Incident, 1960 U.S. 41 USE United States Capitol (Washington, D.C.) BT Military intelligence USE United States Highway 41 U.S. Capitol Complex (Washington, D.C.) Military reconnaissance U.S. 44 USE United States Capitol Complex (Washington, U-Bahn-Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 44 D.C.) USE U-Bahnhof Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 50 U.S. Cleveland Post Office Building (Punta Gorda, Fla.) U-Bahnhof Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 50 UF Cleveland Post Office Building (Punta Gorda, UF Kröpcke, U-Bahnhof (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 51 Fla.) Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 51 BT Post office buildings—Florida U-Bahn-Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 52 U.S. Coast Guard Light Station (Jupiter Inlet, Fla.) BT Subway stations—Germany USE United States Highway 52 USE Jupiter Inlet Light (Fla.) U-Bahnhof Lohring (Bochum, Germany) U.S. -

Temein Languages Comparative Wordlist

Comparative Temein wordlists Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Notes: 1. The principal source for these wordlists are the material collected by Roland Stevenson in the 1970s and early 1980s. For further details see the accompanying paper ‘The Temein languages’. Also incorporated are lexical items form the phonology of T(h)ese by May Yip (2004) and from the unpublished notes of Gerrit Dimmendaal. The materials should therefore be treated as provisional. 2. The comparisons in the final column have been added by Roger Blench and are cross-cited from comparative sources, principally materials from Stevenson. As a consequence, they have not yet been checked against the originals, and newer data that has appeared since Stevenson. I hope to do this in future. 3. Identifying cognates in Nilo-Saharan is not simple; it depends on the analysis of the affixes. In the case of Temein, these are multiple and combined with syllable deletion, can often mean that only a single consonant remains, even between singular and plural in Temein. The comparisons will generally show what element of the word I speculate is the underlying root. But further analysis may change this and thereby the words that are cognate elsewhere. 4. It will be seen that the classification of Temein is far from obvious; although it has slightly more cognates with East Sudanic than other branches of Nilo-Saharan, there are, for example, an elevated number of cognates with Berta. -

The Phonological Segments and Syllabic Structure of Ik

DigitalResources Electronic Working Paper 2011-004 ® The Phonological Segments and Syllabic Structure of Ik Terrill B. Schrock The Phonological Segments and Syllabic Structure of Ik Terrill B. Schrock SIL International® 2011 SIL Electronic Working Papers 2011-004, August 2011 ® ©Terrill B. Schrock and SIL International All rights reserved 2 Abstract The Ik language, spoken in northeast Uganda, is controversially classified as a fringe member of Nilo-Saharan. A more comprehensive description of all levels of the language is needed before the issue of its classification can be resolved. This paper builds on the work of others (e.g. Tucker 1971, Heine 1976, and König 2002) in an attempt to describe the Ik segmental inventory and syllabic structure with an emphasis on phonetic detail. The data come primarily from a list of 1700 Ik words transcribed and analyzed phonologically by the author. In addition to describing the basics of Ik segments and syllables, the paper offers an expanded analysis of Ik velar consonants and the ‗chronolects‘ proposed by Heine (1999). The findings are offered as another piece for the puzzle of Rub (Kuliac) classification. 3 Contents Abstract 1 The Ik language 1.1 Ethnographic context 1.2 Linguistic context 1.3 Previous Research 1.4 The present study 2 Vowels 2.1 Voiceless vowels 2.2 Vowel harmony 2.3 Vowel phonemes 3 Consonants 3.1 Oral consonants 3.1.1 Voiceless plosives 3.1.2 Voiced plosives 3.1.3 Implosives 3.1.4 Ejectives 3.1.5 Voiceless affricates 3.1.6 Voiced affricates 3.1.7 Voiceless fricatives 3.1.8 Voiced fricatives 3.1.9 Liquids 3.2 Nasal consonants 3.3 Semi-vowels 4 Syllable structure 4.1 V 4.2 VC 4.3 CV 4.4 CVC 4.5 CVV 4.6 CGV 4.7 CGVC 4.8 CVVC 4.9 CGVVC 5 Conclusion References 4 1 The Ik language 1.1 Ethnographic context The Ik people live in the Kaabong District in the extreme northeastern corner of Uganda‘s Karamoja Region, where the borderlands of Kenya, Sudan, and Uganda converge. -

2. Historical Linguistics and Genealogical Language Classification in Africa1 Tom Güldemann

2. Historical linguistics and genealogical language classification in Africa1 Tom Güldemann 2.1. African language classification and Greenberg (1963a) 2.1.1. Introduction For quite some time, the genealogical classification of African languages has been in a peculiar situation, one which is linked intricably to Greenberg’s (1963a) study. His work is without doubt the single most important contribution in the classifi- cation history of African languages up to now, and it is unlikely to be equaled in impact by any future study. This justifies framing major parts of this survey with respect to his work. The peculiar situation referred to above concerns the somewhat strained rela- tionship between most historical linguistic research pursued by Africanists in the 1 This chapter would not have been possible without the help and collaboration of various people and institutions. First of all, I would like to thank Harald Hammarström, whose comprehensive collection of linguistic literature enormously helped my research, with whom I could fruitfully discuss numerous relevant topics, and who commented in detail on a first draft of this study. My special thanks also go to Christfried Naumann, who has drawn the maps with the initial assistence of Mike Berger. The Department of Linguistics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology Leipzig under Bernhard Comrie supported the first stage of this research by financing two student assistents, Holger Kraft and Carsten Hesse; their work and the funding provided are gratefully acknowledged. The Humboldt University of Berlin provided the funds for organizing the relevant International Workshop “Genealogical language classification in Africa beyond Greenberg” held in Berlin in 2010 (see https://www.iaaw.hu-berlin. -

LCSH Section U

U-2 (Reconnaissance aircraft) (Not Subd Geog) U.S. 29 U.S. Bank Stadium (Minneapolis, Minn.) [TL686.L (Manufacture)] USE United States Highway 29 BT Stadiums—Minnesota [UG1242.R4 (Military aeronautics)] U.S. 30 U.S. Bicycle Route System (May Subd Geog) UF Lockheed U-2 (Airplane) USE United States Highway 30 UF USBRS (U.S. Bicycle Route System) BT Lockheed aircraft U.S. 31 BT Bicycle trails—United States Reconnaissance aircraft USE United States Highway 31 U.S.-Canada Border Region U-2 (Training plane) U.S. 40 USE Canadian-American Border Region USE Polikarpov U-2 (Training plane) USE United States Highway 40 U.S. Capitol (Washington, D.C.) U-2 Incident, 1960 U.S. 41 USE United States Capitol (Washington, D.C.) BT Military intelligence USE United States Highway 41 U.S. Capitol Complex (Washington, D.C.) Military reconnaissance U.S. 44 USE United States Capitol Complex (Washington, U-Bahn-Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 44 D.C.) USE U-Bahnhof Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 50 U.S. Cleveland Post Office Building (Punta Gorda, Fla.) U-Bahnhof Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 50 UF Cleveland Post Office Building (Punta Gorda, UF Kröpcke, U-Bahnhof (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 51 Fla.) Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 51 BT Post office buildings—Florida U-Bahn-Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 52 U.S. Coast Guard Light Station (Jupiter Inlet, Fla.) BT Subway stations—Germany USE United States Highway 52 USE Jupiter Inlet Light (Fla.) U-Bahnhof Lohring (Bochum, Germany) U.S. -

ATR Vowel Harmony in Ateso

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, Vol. 54, 2018, 61-69 doi: 10.5842/54-0-751 ATR vowel harmony in Ateso David Barasa Linguistics Section, University of Cape Town, South Africa E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Vowels in Ateso, an Eastern Nilotic language, are subject to Advanced Tongue Root (ATR) harmony. Accordingly, the vowels are divided into two harmony sets which differ in terms of tongue root position. The two sets of tongue root position are the Advanced Tongue Root [+ATR] set and the Retracted Tongue Root [-ATR] set. Comparably, Bari and Lutuko, related Eastern Nilotic languages, have a ten-vowel system consisting of five closed and five open vowels, with clearly discernible laws of ATR vowel harmony (Tucker & Bryan 1966ː 444). A similar system applies to Ateso which has the following nine phonemic vowels: /i ɪ e ɛ u ʊ o ɔ a/ and the phonetic vowel [ä]. The presence of the [ä ] variant is conditioned by neighbouring [+ATR] vowels or glides, and hence does not have phonemic status; instead, it is treated as an allophone of /a/. In this paper, I follow the general discussion of vowel harmony in African languages (e.g. by Casali (2003, 2008)), albeit in Ateso. Firstly, I introduce the Ateso vowel articulatory parameters and the phonetic realisation of /a/. Secondly, I show that in Ateso /a/ behaves like an underlying [-ATR] vowel and that, generally, though the ATR affects tongue height and thereby accounts for the relative tongue height, ATR is not a category of tongue height but rather of the position of the tongue root.