A Gift from England. William Ames and His Polemical Discourse Against

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congregational History Society Magazine

ISSN 9B?>–?;<> Congregational History Society Magazine Volume ? Number < Spring ;9:: ISSN 0965–6235 THE CONGREGATIONAL HISTORY SOCIETY MAGAZINE Volume E No B Spring A?@@ Contents Editorial 106 News and Views 106 Correspondence 107 The Hampton Court Conference, the King James Version 108 and the Separatists Alan Argent Locals and Cosmopolitans: Congregational Pastors 124 in Edwardian Hampshire Roger Ottewill The Evangelical Union Academy 138 W D McNaughton Reviews 144 Congregational History Society Magazine, Vol. 6, No 3, 2011 105 EDITORIAL In this issue Roger Ottewill conducts readers to Edwardian Hampshire to meet the county’s Congregational pastors, both local, cosmo-local and cosmopolitan (all terms he explains), among whom we find the influential Welsh wizard, J D Jones of Bournemouth, called “the arch-wangler of Nonconformity” by David Lloyd George, who knew a thing or two about wangling. We travel north of the border to study that understated contribution to Scottish Congregationalism, the Evangelical Union, explicitly through its academy. Lastly, like many others in 2011, we turn aside to mark the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible. In this magazine, our examination of this Jacobean masterpiece involves a consideration of its origins, amid the demands for further reform of the established church, and the growth of those forerunners of Congregationalism, the English separatists. NEWS AND VIEWS We were saddened to learn of the death of John Taylor, for many years the editor of the Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society and, after 1972, of its successor and our sister journal, the Journal of the United Reformed Church History Society . -

The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

FALL 2019 volume 6 issue 1 3 FROM RUTHERFORD HALL Dr. Barry J. York 4 FOUR CENTURIES AGO: AN HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE SYNOD OF DORT Dr. David G. Whitla 16 THE FIRST HEADING: DIVINE ELECTION AND REPROBATION Rev. Thomas G. Reid, Jr. 25 THE SECOND HEADING - CHRIST’S DEATH AND HUMAN REDEMPTION THROUGH IT: LIMITED ATONEMENT AT THE SYNOD OF DORDT AND SOME CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGICAL DEBATES Dr. Richard C. Gamble 33 THE THIRD HEADING: HUMAN CORRUPTION Rev. Keith A. Evans 39 THE FOURTH HEADING: “BOTH DELIGHTFUL AND POWERFUL” THE DOCTRINE OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE IN THE CANONS OF DORT Dr. C. J. Williams 47 THE FIFTH HEADING: THE PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS Dr. Barry J. York STUDY UNDER PASTORS The theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary Description Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is provided freely by RPTS faculty and other scholars to encourage the theological growth of the church in the historic, creedal, Reformed faith. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is published biannually online at the RPTS website in html and pdf. Readers are free to use the journal and circulate articles in written, visual, or digital form, but we respectfully request that the content be unaltered and the source be acknowledged by the following statement. “Used by permission. Article first appeared in Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal, the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (rpts.edu).” e d i t o r s General Editor: Senior Editor: Assistant Editor: Contributing Editors: Barry York Richard Gamble Jay Dharan Tom Reid [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] C. -

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and . -

THE SYNOD of DORT Many Reformed Churches Around the World Commemorate the Great Protestant Reformation Which Begun in Germany on October 31St 1517

THE SYNOD OF DORT Many Reformed Churches around the world commemorate the Great Protestant Reformation which begun in Germany on October 31st 1517. On that providential day, Martin Luther nailed his famed 95 Theses on the door of the castle church of Wittenberg. In no time, without Luther's knowledge, this paper was copied, and reproduced in great numbers with the recently invented printing machine. It was then distributed throughout Europe. This paper was to be used by our Sovereign Lord to ignite the Reformation which saw the release of the true Church of Christ from the yoke and bondage of Rome. Almost five hundred years have gone by since then. Today, there are countless technically Protestant churches (i.e. can trace back to the Reformation in terms of historical links) around the world. But there are few which still remember the rich heritage of the Reformers. In fact, a great number of churches which claim to be Protestant have, in fact, gone back to Rome by way of doctrine and practice, and some even make it their business to oppose the Reformers and their heirs. I am convinced that one of the chief reasons for this state of affair in the Protestant Church is a contemptuous attitude towards past creeds and confessions and the historical battles against heresies. When, for example, there are fundamentalistic defenders of the faith teaching in Bible Colleges, who have not so much as heard of the Canons of Dort or the Synod of Dort, but would lash out at hyper-Calvinism, then you know that something is seriously wrong within the camp. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The Eucharistic liturgy in the English independent, or congregational, tradition: a study of its changing structure and content 1550 - 1974 Spinks, Bryan D. How to cite: Spinks, Bryan D. (1978) The Eucharistic liturgy in the English independent, or congregational, tradition: a study of its changing structure and content 1550 - 1974, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9577/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 BRYAN D. SPINKS THE EUCHARISTIC LITURGY. IN THE ENGLISH INDEPENDENT. OR CONGREGATIONAL,. TRADITION: A STUDY OF ITS CHANGING- STRUCTURE AND CONTENT 1550 - 1974 B.D.-THESIS 1978' The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Chapter .17 of this thesis is based upon part of an unpublished essay 1 The 1'apact of the Liturgical Movement on ii'ucharistic Liturgy of too Congregational Church in Jiu gland and Wales ', successfully presented for the degree of Master of Theology of the University of London, 1972. -

Scholastic Discourse Johannes Maccovius (1588–1644) on Theological and Philosophical Distinctions and Rules

Scholastic Discourse Johannes Maccovius (1588–1644) on Theological and Philosophical Distinctions and Rules Publicaties van het Instituut voor Reformatieonderzoek Publications of the Institute for Reformation Research Editor William den Boer PIRef 4 Instituut voor Reformatieonderzoek Apeldoorn 2009 Scholastic Discourse Johannes Maccovius (1588–1644) on Theological and Philosophical Distinctions and Rules Willem J. van Asselt Michael D. Bell Gert van den Brink Rein Ferwerda Instituut voor Reformatieonderzoek Apeldoorn 2009 © Instituut voor Reformatieonderzoek Apeldoorn 2009 (Theologische Universiteit Apeldoorn) ISBN 978-90-79771-05-9 NUR 704 On the cover: University of Franeker, ca. 1700, in: Andries Schoemaker, ‘Be- schrijving van Friesland’. Ms 998 Tresoar, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands Printed by: Drukkerij Verloop, Alblasserdam, The Netherlands Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen, of enige andere manier, zonder vooraf- gaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recor- ding or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Preface One of the best ways to acquaint oneself with an unfamiliar (or even suppos- edly familiar) view is to allow its advocates to speak for themselves. This book by Johannes Maccovius (1588-1644) does just that; it presents a new critical Latin edition and an English translation of his seminal work on theological and philosophical distinctions. During most of the seventeenth century it was used as a classroom book at Reformed universities and academies from England to Transylvania. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

Home of Rev. Thomas Parker and Rev. James Noyes

HOME OF REV. THOMAS PARKER AND REV. JAMES NOYES THE FIRST PARISH Newbury, Massachusetts 1635 - 1935 Editors ELIZA ADAMS LITTLE LUCRETIA LITTLE ILSLEY Contributors MARION STACKPOLE BAILEY HARRIOT WITHINGTON COLMAN ELIZABETH HALE LITTLE ILSLEY RUSSELL LEIGH JACKSON MARGARET ILSLEY PRITCHARD WORTHEN HUDSON TAYLOR ROLA.i~D HORTON WOODWELL Newburyport 1935 NEWS PuBLISHING Co., INC. PRINTERS 1935 PREFACE The committee for the celebration of the tercentenary of the First Parish, Newbury, felt that its first duty was to awaken in the minds of the younger members of the parish an appreciation of three hundred years of community life and worship, and its second duty, to arrange for the preservation in suitable form of hitherto scattered records and traditions. Both of these purposes are, it is hoped, ac complished in the publication of this vo]ume. Publication has been made possible through the co-operation of the editors and contributors listed on the title page and of the fol lowing guarantors: Caroline L. Colman, Harriot W. Colman, Florence E. Dibble, C. Stanley Harrison, Maria P. Humphreys, William Ilsley, Agnes L. Little, Eliza A. Little., Hallet W. Noyes, Walter R. Noyes, Arthur S. Page, Joseph D. Rolfe, Roland H. W oodwell. The committee wishes to express its gratitude to Mrs. Annie K. Rarnett and to Mr. Gordon Hutchins fo.r making available the manu script diary of Miss Alice Tucker, and to Miss Agnes L. Little and Mr. Roland H. W oodwell for assistance in details of publication. Eliza A. Little, Chairman Rev. Charles S. Holton, ex officio Deacon Ed,vin Ilsley Elizabeth H. -

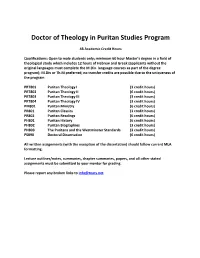

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

April 2016 Issue of the Protestant Re- Formed Theological Journal

Editor’s Notes You hold in your hand the April 2016 issue of the Protestant Re- formed Theological Journal. Included in this issue are three articles and a number of book reviews, some of them rather extensive. We are confident that you will find the contents of this issue worth the time you spend in reading—well worth the time. Few doctrines of the faith are more precious to the Reformed be- liever than the doctrine of God’s everlasting covenant of grace. Few books of the Bible are dearer to the saints than the book of Psalms. Prof. Dykstra puts those two together in the first of two articles on “God’s Covenant of Grace in the Psalms.” You will find his article both instructive and edifying. The Reverend Joshua Engelsma, pastor of the Protestant Reformed Church in Doon, Iowa contributes a very worthwhile article on Jo- hannes Bogerman. Bogerman was the man chosen to be president of the great Synod of Dordt, 1618-’19. The article not only traces the life and public ministry of Bogerman, but demonstrates clearly the direct influence that he had on the formulation of the articles in the First Head of doctrine in the Canons of Dordt. This is an especially appropriate article as the Reformed churches around the world prepare to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Synod of Dordt in 2018-’19. The Protestant Reformed Seminary is planning to hold a conference to commemorate this very significant anniversary. We will keep our readers informed of the specifics of the conference as they are arranged.