April 2016 Issue of the Protestant Re- Formed Theological Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 11 29#2.Indd

Volume XXIX • Number 2 • 2011 Historical Magazine of The Archives Calvin College and Calvin Theological Seminary 1855 Knollcrest Circle SE Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546 pagepage 7 page 21 (616) 526-6313 Origins is designed to publicize 2 From the Editor 12 Brother Ploeg: A Searching Saint and advance the objectives of or a Burr under the Saddle? 4 Herbert J. Brinks The Archives. These goals Janet Sjaarda Sheeres 1935-2011 include the gathering, 20 “Now I will tell you children . .” organization, and study of 5 Harmannus “Harry” Westers: historical materials produced by Hendrik De Kruif’s Account Aquaculturist of His Immigration the day-to-day activities of the Harold and Nancy Gazan Christian Reformed Church, Jan Peter Verhave its institutions, communities, and people. Richard H. Harms Editor Hendrina Van Spronsen Circulation Manager Tracey L. Gebbia Designer H.J. Brinks Harry Boonstra Janet Sheeres Associate Editors James C. Schaap Robert P. Swierenga Contributing Editors HeuleGordon Inc. ppageage 37 page 40 Printer 27 “When I Was a Kid,” part IV 42 Book Reviews Meindert De Jong, Harry Boonstra and with Judith Hartzell Eunice Vanderlaan Cover photo: 40 Rev. Albertus Christiaan 45 Book Notes Herbert J. Brinks, 1935-2011 Van Raalte 1811–1876 46 For the Future upcoming Origins articles 47 Contributors from the editor . raising of fi sh under controlled condi- your family history that we can share tions to restock commercially over- with others. fi shed waters. Janet Sjaarda Sheeres, a contributing editor, writes of a News from the Archives nineteenth-century immigrant to West During the summer we received the Michigan who had trouble settling in a extensive collection of the papers religious home, while Jan Peter Verhave of Vernon Ehlers, who served as a Time to Renew Your Subscription introduces and translated the account representative in Kent County, ten It is time to remind you, as we do of Hendrik De Kruif’s emigration years in Lansing, and eighteen years in in every fall issue, that it is time to from Zeeland to Zeeland, Michigan. -

4 Reformed Orthodoxy

Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology Belt, H. van der Citation Belt, H. van der. (2006, October 4). Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). id7775687 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com 4 Reformed Orthodoxy The period of Reformed orthodoxy extends from the Reformation to the time that liberal theology became predominant in the European churches and universities. During the period the Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican churches were the official churches in Protestant countries and religious polemics between Catholicism and Protestantism formed an integral part of the intense political strife that gave birth to modern Europe. Reformed orthodoxy is usually divided into three periods that represent three different stages; there is no watershed between these periods and it is difficult to “ ” determine exact dates. During the period of early orthodoxy the confessional and doctrinal codifications of Reformed theology took place. This period is characterized by polemics against the Counter-Reformation; it starts with the death of the second- generation Reformers (around 1565) and ends in the first decades of the seventeenth century.1 The international Reformed Synod of Dort (1618-1619) is a useful milestone, 2 “ because this synod codified Reformed soteriology. -

The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

FALL 2019 volume 6 issue 1 3 FROM RUTHERFORD HALL Dr. Barry J. York 4 FOUR CENTURIES AGO: AN HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE SYNOD OF DORT Dr. David G. Whitla 16 THE FIRST HEADING: DIVINE ELECTION AND REPROBATION Rev. Thomas G. Reid, Jr. 25 THE SECOND HEADING - CHRIST’S DEATH AND HUMAN REDEMPTION THROUGH IT: LIMITED ATONEMENT AT THE SYNOD OF DORDT AND SOME CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGICAL DEBATES Dr. Richard C. Gamble 33 THE THIRD HEADING: HUMAN CORRUPTION Rev. Keith A. Evans 39 THE FOURTH HEADING: “BOTH DELIGHTFUL AND POWERFUL” THE DOCTRINE OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE IN THE CANONS OF DORT Dr. C. J. Williams 47 THE FIFTH HEADING: THE PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS Dr. Barry J. York STUDY UNDER PASTORS The theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary Description Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is provided freely by RPTS faculty and other scholars to encourage the theological growth of the church in the historic, creedal, Reformed faith. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is published biannually online at the RPTS website in html and pdf. Readers are free to use the journal and circulate articles in written, visual, or digital form, but we respectfully request that the content be unaltered and the source be acknowledged by the following statement. “Used by permission. Article first appeared in Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal, the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (rpts.edu).” e d i t o r s General Editor: Senior Editor: Assistant Editor: Contributing Editors: Barry York Richard Gamble Jay Dharan Tom Reid [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] C. -

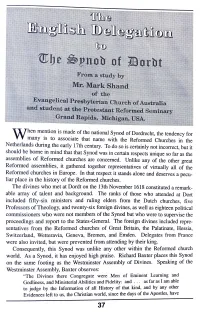

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and . -

THE SYNOD of DORT Many Reformed Churches Around the World Commemorate the Great Protestant Reformation Which Begun in Germany on October 31St 1517

THE SYNOD OF DORT Many Reformed Churches around the world commemorate the Great Protestant Reformation which begun in Germany on October 31st 1517. On that providential day, Martin Luther nailed his famed 95 Theses on the door of the castle church of Wittenberg. In no time, without Luther's knowledge, this paper was copied, and reproduced in great numbers with the recently invented printing machine. It was then distributed throughout Europe. This paper was to be used by our Sovereign Lord to ignite the Reformation which saw the release of the true Church of Christ from the yoke and bondage of Rome. Almost five hundred years have gone by since then. Today, there are countless technically Protestant churches (i.e. can trace back to the Reformation in terms of historical links) around the world. But there are few which still remember the rich heritage of the Reformers. In fact, a great number of churches which claim to be Protestant have, in fact, gone back to Rome by way of doctrine and practice, and some even make it their business to oppose the Reformers and their heirs. I am convinced that one of the chief reasons for this state of affair in the Protestant Church is a contemptuous attitude towards past creeds and confessions and the historical battles against heresies. When, for example, there are fundamentalistic defenders of the faith teaching in Bible Colleges, who have not so much as heard of the Canons of Dort or the Synod of Dort, but would lash out at hyper-Calvinism, then you know that something is seriously wrong within the camp. -

Understanding Calvinism: B

Introduction A. Special Terminology I. The Persons Understanding Calvinism: B. Distinctive Traits A. John Calvin 1. Governance Formative Years in France: 1509-1533 An Overview Study 2. Doctrine Ministry Years in Switzerland: 1533-1564 by 3. Worship and Sacraments Calvin’s Legacy III. Psycology and Sociology of the Movement Lorin L Cranford IV. Biblical Assessment B. Influencial Interpreters of Calvin Publication of C&L Publications. II. The Ideology All rights reserved. © Conclusion INTRODUCTION1 Understanding the movement and the ideology la- belled Calvinism is a rather challenging topic. But none- theless it is an important topic to tackle. As important as any part of such an endeavour is deciding on a “plan of attack” in getting into the topic. The movement covered by this label “Calvinism” has spread out its tentacles all over the place and in many different, sometimes in conflicting directions. The logical starting place is with the person whose name has been attached to the label, although I’m quite sure he would be most uncomfortable with most of the content bearing his name.2 After exploring the history of John Calvin, we will take a look at a few of the more influential interpreters of Calvin over the subsequent centuries into the present day. This will open the door to attempt to explain the ideology of Calvinism with some of the distinctive terms and concepts associated exclusively with it. I. The Persons From the digging into the history of Calvinism, I have discovered one clear fact: Calvinism is a religious thinking in the 1500s of Switzerland when he lived and movement that goes well beyond John Calvin, in some worked. -

WILLIAM VAN DOODEWAARD, HUNTINGTON UNIVERSITY a Transplanted Church: the Netherlandic Roots and Development of the Free Reformed Churches of North America

WILLIAM VAN DOODEWAARD, HUNTINGTON UNIVERSITY A Transplanted Church: the Netherlandic Roots and Development of the Free Reformed Churches of North America Introduction and denominational development only came two hundred years later. These later arriv The history of Dutch Reformed denomina als reflected the intervening development of tions in North America dates back almost the church in the Netherlands, many now 400 years to the time when The Netherlands having a varied history of secession from was a maJor sea-power with colonial ambi the state church and ensuing union with tion. In 1609 the explorer Henry Hudson or separation from other secession groups. was sent out by the Dutch to examine pos Most of these immigrants settled into already sibilities for a colony in the New World. established Christian Reformed Church con Dutch colonization began soon afterwards gregations, some joined congregations of the with the formation of New Netherland Reformed Church in America, some chose under the banner of the Dutch West India existing Canadian Protestant denominations, Company. The colony at its peak consisted and the remainder established new denomi of what today makes up the states of New nations corresponding to other Dutch Re York, New Jersey, and parts of Delaware and formed denominations in the Netherlands.4 Connecticut.] With the colony came the establishment of the first Dutch Reformed One of the new presences in the late 1940s church in 1628 in the wilderness village of and early 1950s was a qUickly developing New Amsterdam. This small beginning of a association of independent Dutch Reformed viable Dutch community set in motion cen congregations sharing similar theological turies of Dutch migration to North America, convictions and seceder roots. -

'Dimittimini, Exite'

Seite 1 von 13 ‘Dimittimini, exite’ Debating Civil and Ecclesiastical Power in the Dutch Republic 1. Dordrecht, Monday 14 January 1619. ‘You are cast away, go! You have started with lies, you have ended with lies. Dimittimini, exite’. The end was bitter and dramatic. The chairman of the Synod of Dort, Johannes Bogerman, lost his patience. Roaring, as some reports put it, he ordered Simon Episcopius, who had just, in equally outspoken terms, accused Bogerman of committing acts of slavery, to leave. Episcopius and his fellow Arminians left. As usual the two great --indeed massive-- seventeenth century accounts of the Synod, those of Johannes Uytenbogaert on the Arminian and of Jacobus Trigland on the orthodox Calvinist side, differ strongly in their account and appreciation of what happened at the Synod of Dort1. But they agreed Dort marked a schism; Dutch Reformed Protestantism had split apart. In almost all 57 fateful sessions of the synod which had started on 13 November 1618 the debate had been bitter, though invariably participants asked for moderation, temperance and sobriety. The Synod vacillated between the bitterness of intense theological dispute and a longing for religious peace, between the relentless quest for truth and the thirst for toleration. For over ten years Dutch Reformed Protestants had been arguing, with increasing intensity and rancour. Divisions and issues were manifold with those, such as Simon 1 See Johannes Uytenbogaert, Kerckelicke Historie, Rotterdam, 1647, pp. 1135-1136 and Jacobus Trigland, Kerckelycke Geschiedenissen, begrypende de swaere en Bekommerlijcke Geschillen, in de Vereenigde Nederlanden voorgevallen met derselver Beslissinge, Leiden, 1650, p 1137. -

Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State

MWP – 2014/05 Max Weber Programme Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State AuthorStephan Author Leibfried and and Author Wolfgang Author Winter European University Institute Max Weber Programme Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State Stephan Leibfried and Wolfgang Winter Max Weber Lecture No. 2014/05 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1830-7736 © Stephan Leibfried and Wolfgang Winter, 2014 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract Depictions of ships of church and state have a long-standing religious and political tradition. Noah’s Ark or the Barque of St. Peter represent the community of the saved and redeemed. However, since Plato at least, the ship also symbolizes the Greek polis and later the Roman Empire. From the fourth century ‒ the Constantinian era ‒ on, these traditions merged. Christianity was made the state religion. Over the course of a millennium, church and state united in a religiously homogeneous, yet not always harmonious, Corpus Christianum. In the sixteenth century, the Reformation led to disenchantment with the sacred character of both church and state as mediators indispensible for religious and secular salvation. -

“Calvinism” and “Arminianism”

“Calvinism” and “Arminianism” The “Low Countries” Early Phases of Dutch Reformation • The Netherlands had early been influenced by Lutheranism, then Anabaptism grew rapidly there. • 30 Luther works in Dutch by 1530 • Dutch Anabaptist “Uproar”, 1535 Very little Calvinist influence before 1566 The priest brought the oil, but there‟s no salad in the house. • In 1566 the congregations 1,000s at Calvinist Field began to worship in the open fields, sometimes Revivals! under armed guard and with barricaded approaches. A congregation of seven or eight thousand met in a field near Ghent; fifteen thousand outside Antwerp; twenty thousand at a bridge near Tournai. – Owen Chadwick, The Reformation, p.169. 1561, Belgic Confession • "Belgic Confession" 37 articles written by Guido de Brès, a Reformer in the southern Low Countries (now Belgium) – Patterned after a Beza confession – Predestination – Infant baptism – Spiritual presence in Lord‟s Supper – Discipline a mark of the true church 1566, “Wonder Year": Waves of Iconoclasm • “Stained glass was smashed, missals ripped, monasteries plundered; images were desecrated with blood and beer; and letters of indulgence used as lavatory paper.” – Brian Moynahan, The Faith, A History of Christianity. Literally hundreds and Hundreds of Churches Forcibly Cleansed by Mobs “Soon, the iconoclasm swelled into a character and a scale unmatched in the history of the European Reformation.” Philip Benedict, Christ‟s Churches Purely Reformed Aftermath of Iconoclasm King Philip II of Spain I will not be a King of Heretics! • During the time of Philip II, all the Dutch Protestants were severely persecuted. • There is no accurate record of the number of Protestant martyrs in the Netherlands during this time. -

Prairie Premillennialism: Dutch Calvinist Chiliasm in Iowa 1847-1900, Or the Long Shadow of Hendrik Pieter Scholte

Prairie Premillennialism: Dutch Calvinist Chiliasm in Iowa 1847-1900, or the Long Shadow of Hendrik Pieter Scholte Earl Wm. Kennedy Local history as an academic discipline has gained considerable respectability lately, as has the study of American ethnic groups. I am writing a book which compares the Reformed Church in America (RCA) and the Christian Reformed Church in North America (CRC) in the Midwest in the last decades of the nineteenth century and first decades of the twentieth century, with special reference to the churches of Orange City (and the surrounding area of Sioux County and Northwestern Iowa), against their background in the Netherlands and the larger church situation in the United States. My study will, I hope, contribute to knowledge of the life and thought of immigrant ethnic churches in our country about a century ago by examining the Orange City-area microcosm of the mini-macrocosm of the Dutch Reformed immigration to the American Midwest. Little has been published comparing the RCA and the CRC. One of my aims is to see how, when, and to what extent these denominations became "Americanized. " I also see this work as a contribution to mutual understanding between the RCA and the CRC. The present article is largely the forerunner of a proposed chapter on premillennialism, which will show that the midwestern, immigrant RCA, especially in Iowa, was receptive to premillenarian teaching, whereas the CRC was closed to it. This divergence reflects the fact that the two groups were formatively influenced by different branches of the 1834 pietist, Calvinist Afscheiding (Secession) in the Netherlands. -

Joel R. Beeke 2917 Leonard, N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49525 Office: 616-432-3403 • Home: 616-285-8102 E-Mail: [email protected] • Website

Joel R. Beeke 2917 Leonard, N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49525 Office: 616-432-3403 • Home: 616-285-8102 e-mail: [email protected] • website: www.heritagebooks.org EDUCATION: Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan (1971-73) Thomas A. Edison College (B.A. with specialization in religion) Netherlands Reformed Theological School, St. Catharines, Ontario (1974-78, equiv. to M. Div. & Licentiate in Ministry) Westminster Theological Seminary (1982-1988; Ph.D. in Reformation and Post-Reformation Theology) EXPERIENCE: 1978-1981: Pastor, Netherlands Reformed Congregation, Sioux Center, Iowa. As sole minister, in charge of the full scope of pastoral duties for the church membership of 687 (1978) to 729 (1981) persons. Additionally, appointed to serve as moderator for the following vacant churches: Neth. Reformed Congregation, Rock Valley, Iowa (membership: 900) Neth. Reformed Congregation, Corsica, South Dakota (membership: 150) Neth. Reformed Congregation, Sioux Falls, South Dakota (membership: 100) Instrumental in establishing and commencing the Netherlands Reformed Christian School, Rock Valley, Iowa, as board president (K-8, 225 students) Denominational appointments: Clerk of the Netherlands Reformed Synod, 1980-92. Clerk of Classes, 1978-79. President of Classes, 1979-81. Vice-president of the Neth. Reformed General Mission, 1980-82. President of Neth. Reformed Book and Publishing Committee, 1980-93. Denominational Appointee to Government for Netherlands Reformed Congregations, 1980-86. Office-bearer Conference Speaker and Committee Member (clerk), 1980-93. 1981-1986: Pastor, Ebenezer Netherlands Reformed Church, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey As sole minister, in charge of the full scope of pastoral duties for the church membership of 689 (1981) to 840 (1986) persons. Additionally, appointed to serve as moderator for the following vacant churches: Neth.