'Dimittimini, Exite'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dutch in the Early Modern World David Onnekink , Gijs Rommelse Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-12581-0 — The Dutch in the Early Modern World David Onnekink , Gijs Rommelse Frontmatter More Information The Dutch in the Early Modern World Emerging at the turn of the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic rose to become a powerhouse of economic growth, artistic creativity, military innovation, religious tolerance and intellectual development. This is the first textbook to present this period of early modern Dutch history in a global context. It makes an active use of illustrations, objects, personal stories and anecdotes to present a lively overview of Dutch global history that is solidly grounded in sources and literature. Focusing on themes that resonate with contemporary concerns, such as overseas exploration, war, slavery, migration, identity and racism, this volume charts the multiple ways in which the Dutch were connected with the outside world. It serves as an engaging and accessible intro- duction to Dutch history, as well as a case study in early modern global expansion. david onnekink is Assistant Professor in Early Modern International Relations at Utrecht University. He has previously held a position at Leiden University, and was a visiting professor at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, and the University of California, Los Angeles. He has been a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Humanities at Edinburgh (2004), Het Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam (2016–2017) and the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study (2016). He is the author of Reinterpreting the Dutch Forty Years War (2016), and edited volumes on War and Religion after Westphalia, 1648–1713 (2009) and Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650–1750) (2011), also with Gijs Rommelse. -

The Theology of Dort

Program The Theology of Dort (1618–1619) Confessional Consolidation, Conflictual Contexts, and Continuing Consequences Groningen, May 8–9, 2019 Dutch theological faculties.at the Synod (painting Museum of Dordrecht) Confessional Consolidation and Conflictual Contexts (Wednesday) Time Wednesday morning (plenary) ~ Zittingszaal 10.00 Welcome by the dean of the faculty, prof.dr. Mladen Popovic and Brief introduction by Henk van den Belt 10.15 Dr. Dolf te Velde, Theological University of Kampen, Justified by Faith? Franciscus Gomarus on the Crucial Issue with Jacob Arminius 11.00 Coffeebreak 11.15 Prof.dr. Volker Leppin, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, A disliked doctrine: Predestination, Dort and the Lutherans 12.00 Dr. Harm Goris, Tilburg School of Catholic Theology, Total depravity or relapse into natural state? Roman Catholic views on the effects of the Fall 12.45 Lunch Wednesday afternoon ~ Zittingszaal Zaal 130 14.00 Jacob van Sluis, Groningen University Library and Jeannette Kreijkes, PhD Groningen, Did the Tresoar Leeuwarden, The Franeker Academy and the Synod of Dort Consider Chrysostom a Semi- Synod of Dort Pelagian? Continuity and Discontinuity of Early Christian Views in the Reformed Tradition 14.30 Bert Koopman, independent scholar, Preparatory work, Prof.dr. Wim van Vlastuin, Vrije Universiteit rejected by the front door, stealthily admitted by the back Amsterdam, Retrieving the doctrine of the door apostasy of the saints in the ‘Remonstrantie 15.00 Coffee / Tea 15.30 Prof.dr. Wim Moehn, Protestant Theological University, Dr. Pieter L. Rouwendal, independent scholar, Debating regeneration – from baptismal water to seed of A Slight Modification in a Classic Formula: regeneration. the Reformed Theologians at the Synod of Dort on the Extent of the Atonement 16.00 Prof.dr. -

4 Reformed Orthodoxy

Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology Belt, H. van der Citation Belt, H. van der. (2006, October 4). Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). id7775687 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com 4 Reformed Orthodoxy The period of Reformed orthodoxy extends from the Reformation to the time that liberal theology became predominant in the European churches and universities. During the period the Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican churches were the official churches in Protestant countries and religious polemics between Catholicism and Protestantism formed an integral part of the intense political strife that gave birth to modern Europe. Reformed orthodoxy is usually divided into three periods that represent three different stages; there is no watershed between these periods and it is difficult to “ ” determine exact dates. During the period of early orthodoxy the confessional and doctrinal codifications of Reformed theology took place. This period is characterized by polemics against the Counter-Reformation; it starts with the death of the second- generation Reformers (around 1565) and ends in the first decades of the seventeenth century.1 The international Reformed Synod of Dort (1618-1619) is a useful milestone, 2 “ because this synod codified Reformed soteriology. -

Finding Certainty in an Age of Uncertainty the Early Eighteenth-Century Cocceian Turn Towards Natural Theology

Finding certainty in an age of uncertainty The early eighteenth-century Cocceian turn towards natural theology Masterthesis by: Niels Visscher – 3237494 Primary reader: Prof.dr. M. Mostert Secondary reader: Prof.dr. W. Mijnhardt Medieval Studies University Utrecht 19-07-2013 1 Content Preface 3 Introduction 4 Chapter I: The crisis of the Reformed mind 9 The Reformed theological system 9 Scripture and the Reformed articles of faith 10 The intellectual foundations of Reformed theology 12 Reformed theology and the challenge of Cartesianism 13 The challenge of Cartesian philosophy 14 The Voetian response to the new philosophy 15 The Cartesian philosophers 16 The Cocceian theologians 18 The rise of philosophical radicalism 20 Chapter II: Living during the crisis of the Reformed mind 24 A child prodigy 24 The University of Franeker 25 Education at the University of Franeker 27 The status of reason and the divinity of Scripture 28 Minister of the Divine Word 29 Professor of at the University of Franeker 31 The last of the Cartesians 32 Chapter III: Vindicating the divinity of Scripture 34 The Reformed view on natural theology 35 The characteristics of natural theology 36 The new approach to natural theology 37 Prolegomena 38 The doctrine of God 40 Natural religion 41 The necessity and divinity of supernatural revelation 42 Ruardus Andala on natural theology 44 Prolegomena 45 The doctrine of God 46 Natural religion 47 The necessity and divinity of supernatural revelation 48 A turn towards rationalism? 49 Conclusion 51 Bibliography 53 2 Preface Trying to obtain a master’s degree in Medieval Studies by writing a thesis on seventeenth- and eight- eenth-century developments in theology and philosophy – this turn of events will probably amaze many readers. -

'Elke Daad Is Een Werk'

‘Elke daad is een werk’ Alexander Comrie (1706-1774) over de verschillen tussen de remonstrantse en de gereformeerde rechtvaardigingsleer G.A. van den Brink Abstract The Dutch theologian Alexander Comrie (1706-1774) opposed Amyraldism vehemently. He downplayed the role of the act of faith in justification, for ‘every act is a work of man.’ However, Comrie offended many of his colleagues by suggesting that anyone who regarded the act of faith as the instrument involved in justification, was dogmatically speaking to be considered an amyraldian or even an arminian. Comrie was, in turn, accused of antinomianism. In this article the dogmatic position of Comrie is analyzed. His view on the material cause and especially on the formal cause of justification is compared with the views by Arminius, Lubbertus and others. It is concluded that Comrie mistakenly regarded the immediacy of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness as fundamental for the Reformed doctrine of justification. 1 Inleiding Toen de Schots-Nederlandse theoloog Alexander Comrie (1706-1774)1 in 1753 zijn verklaring van Zondag 1-7 van de Heidelbergse Catechismus publi- ceerde, brak er een storm van protest los. Geheel onbegrijpelijk was de verbol- genheid niet: Comrie schroomde niet om velen van zijn collega’s te bestempe- len als mensen die, al of niet bewust, een arminiaanse en semipelagiaanse opvatting huldigden ten aanzien van de leer van de rechtvaardiging. De bezorgdheid van Comrie werd ingegeven door de controverse rondom de Zwolse predikant Antonius van der Os (1722-1807).2 Deze was aangeklaagd 1 A.G. Honig, Alexander Comrie, Utrecht 1892; R.A. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Righteous Citizens: The Lynching of Johan and Cornelis DeWitt,The Hague, Collective Violens, and the Myth of Tolerance in the Dutch Golden Age, 1650-1672 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2636q95m Author DeSanto, Ingrid Frederika Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Righteous Citizens: The Lynching of Johan and Cornelis DeWitt, The Hague, Collective Violence, and the Myth of Tolerance in the Dutch Golden Age, 1650-1672. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Ingrid Frederika DeSanto 2018 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Righteous Citizens: The Lynching of Johan and Cornelis DeWitt, The Hague, Collective Violence, and the Myth of Tolerance in the Dutch Golden Age, 1650-1672 by Ingrid Frederika DeSanto Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles Professor Margaret C Jacob, Chair In The Hague, on August 20 th , 1672, the Grand Pensionary of Holland, Johan DeWitt and his brother Cornelis DeWitt were publicly killed, their bodies mutilated and hanged by the populace of the city. This dissertation argues that this massacre remains such an unique event in Dutch history, that it needs thorough investigation. Historians have focused on short-term political causes for the eruption of violence on the brothers’ fatal day. This work contributes to the existing historiography by uncovering more long-term political and social undercurrents in Dutch society. In doing so, issues that may have been overlooked previously are taken into consideration as well. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. JOHANNES SWARTENHENGST (1644-1711): A DUTCH CARTESIAN IN THE HEAT OF BATTLE ESTER BERTRAND PHD THESIS UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH & FREE UNIVERSITY OF BRUSSELS 2014 2 JOHANNES SWARTENHENGST (1644-1711): A DUTCH CARTESIAN IN THE HEAT OF BATTLE ESTER BERTRAND The painting on the title page, entitled The Stallion, is by the accomplished Dutch painter of equestrian scenes, Philips Wouwerman (1619-1668). In agreement with the Creative Commons Licence this copy was retrieved from the following website: http://www.wouwerman.org/ PHD THESIS UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH & FREE UNIVERSITY OF BRUSSELS JUNE 2014 Funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), the Free University of Brussels, and the University of Edinburgh I, Ester Bertrand, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 95.000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. -

The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

FALL 2019 volume 6 issue 1 3 FROM RUTHERFORD HALL Dr. Barry J. York 4 FOUR CENTURIES AGO: AN HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE SYNOD OF DORT Dr. David G. Whitla 16 THE FIRST HEADING: DIVINE ELECTION AND REPROBATION Rev. Thomas G. Reid, Jr. 25 THE SECOND HEADING - CHRIST’S DEATH AND HUMAN REDEMPTION THROUGH IT: LIMITED ATONEMENT AT THE SYNOD OF DORDT AND SOME CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGICAL DEBATES Dr. Richard C. Gamble 33 THE THIRD HEADING: HUMAN CORRUPTION Rev. Keith A. Evans 39 THE FOURTH HEADING: “BOTH DELIGHTFUL AND POWERFUL” THE DOCTRINE OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE IN THE CANONS OF DORT Dr. C. J. Williams 47 THE FIFTH HEADING: THE PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS Dr. Barry J. York STUDY UNDER PASTORS The theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary Description Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is provided freely by RPTS faculty and other scholars to encourage the theological growth of the church in the historic, creedal, Reformed faith. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is published biannually online at the RPTS website in html and pdf. Readers are free to use the journal and circulate articles in written, visual, or digital form, but we respectfully request that the content be unaltered and the source be acknowledged by the following statement. “Used by permission. Article first appeared in Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal, the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (rpts.edu).” e d i t o r s General Editor: Senior Editor: Assistant Editor: Contributing Editors: Barry York Richard Gamble Jay Dharan Tom Reid [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] C. -

Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2-24-2014 Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672 David Beeler University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Beeler, David, "Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4983 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672 by David Beeler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Annette Cozzi, Ph.D. Cornelis “Kees” Boterbloem, Ph.D. Brendan Cook, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 24, 2014 Keywords: colonialism, foreign, otherness, maidservant, Burgher, mercenary Copyright © 2014, David Beeler Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................................ii -

University of Groningen Developments in Structuring Of

University of Groningen Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology van den Belt, Hendrik Published in: Reformation und Rationalität IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Final author's version (accepted by publisher, after peer review) Publication date: 2015 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H. (2015). Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology: The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625) as Example. In H. J. Selderhuis, & E-J. Waschke (Eds.), Reformation und Rationalität (pp. 289-311). (Refo500 Academic Studies; Vol. 17). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 11-02-2018 1 Henk van den Belt 2 3 4 Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology: 5 6 The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625) as Example. 7 8 9 10 11 12 Abstract 13 14 The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625), an influential handbook of Reformed 15 dogmatics, began as a cycle of disputations. -

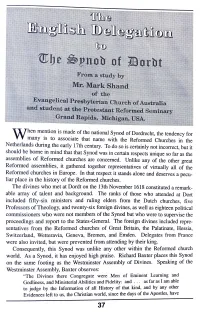

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and . -

The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip Van Limborch: a Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism

The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip van Limborch: A Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism By John Mark Hicks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Westminster Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy 1985 Faculty Advisor: Dr. Richard C. Gamble Second Faculty Reader: Mr. David W. Clowney Chairman, Field Committee: Dr. D. Claire Davis External Reader: Dr. Carl W. Bangs 2 Dissertation Abstract The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip van Limborch: A Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism By John Mark Hicks The dissertation addresses the problem of the theological relationship between the theology of Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609) and the theology of Philip van Limborch (1633-1712). Arminius is taken as a representative of original Arminianism and Limborch is viewed as a representative of developed Remonstrantism. The problem of the dissertation is the nature of the relationship between Arminianism and Remonstrantism. Some argue that the two systems are the fundamentally the same, others argue that Arminianism logically entails Remonstrantism and others argue that they ought to be radically distinguished. The thesis of the dissertation is that the presuppositions of Arminianism and Remonstrantism are radically different. The thesis is limited to the doctrine of grace. There is no discussion of predestination. Rather, the thesis is based upon four categories of grace: (1) its need; (2) its nature; (3) its ground; and (4) its appropriation. The method of the dissertation is a careful, separate analysis of the two theologians.