The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Five Points of Calvinism

• TULIP The Five Points of Calvinism instructor’s guide Bethlehem College & Seminary 720 13th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55415 612.455.3420 [email protected] | bcsmn.edu Copyright © 2007, 2012, 2017 by Bethlehem College & Seminary All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, modified, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Scripture taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Copyright © 2007 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. • TULIP The Five Points of Calvinism instructor’s guide Table of Contents Instructor’s Introduction Course Syllabus 1 Introduction from John Piper 3 Lesson 1 Introduction to the Doctrines of Grace 5 Lesson 2 Total Depravity 27 Lesson 3 Irresistible Grace 57 Lesson 4 Limited Atonement 85 Lesson 5 Unconditional Election 115 Lesson 6 Perseverance of the Saints 141 Appendices Appendix A Historical Information 173 Appendix B Testimonies from Church History 175 Appendix C Ten Effects of Believing in the Five Points of Calvinism 183 Instructor’s Introduction It is our hope and prayer that God would be pleased to use this curriculum for his glory. Thus, the intention of this curriculum is to spread a passion for the supremacy of God in all things for the joy of all peoples through Jesus Christ. This curriculum is guided by the vision and values of Bethlehem College & Seminary which are more fully explained at bcsmn.edu. At the Bethlehem College & Semianry website, you will find the God-centered philosophy that undergirds and motivates everything we do. -

Calvinism and Limited Atonement Isaiah 53:6; Hebrews 2:9 and Others

CALVINISM AND LIMITED ATONEMENT ISAIAH 53:6; HEBREWS 2:9 AND OTHERS Text: Isaiah 53:6; Hebrews 2:9 Isaiah 53:6 6 All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the LORD hath laid on him the iniquity of us all. Hebrews 2:9 9 But we see Jesus, who was made a little lower than the angels for the suffering of death, crowned with glory and honour; that he by the grace of God should taste death for every man. Introduction: Of the five points of Calvin’s philosophy, (and I call it "philosophy" instead of "theology" because in this particular point, it is 100% contrary to the revealed will of God as given to us in the Bible, therefore, it cannot properly be called "theology") the weakest link is his so-called false teaching on the "LIMITED ATONEMENT," or the "L" of the T.U.L.I.P. acronym of Calvinism. - 1 - It is interesting to me that this point is the center of this deadly flower. We will consider the Basic Definition, Blatant Distortion, and the Biblical Dispute, of Limited Atonement. 1. BASIC DEFINITION OF LIMITED ATONEMENT By “Limited Atonement” we refer to the belief which states that Christ did not die for “all or everyone” but rather died only for the elect. While it is true that only the saved benefit from Christ’s death on the cross, Christ died for all people. 1 John 2:1-2 1 My little children, these things write I unto you, that ye sin not. -

Total Depravity

TULIP: A FREE GRACE PERSPECTIVE PART 1: TOTAL DEPRAVITY ANTHONY B. BADGER Associate Professor of Bible and Theology Grace Evangelical School of Theology Lancaster, Pennsylvania I. INTRODUCTION The evolution of doctrine due to continued hybridization has pro- duced a myriad of theological persuasions. The only way to purify our- selves from the possible defects of such “theological genetics” is, first, to recognize that we have them and then, as much as possible, to set them aside and disassociate ourselves from the systems which have come to dominate our thinking. In other words, we should simply strive for truth and an objective understanding of biblical teaching. This series of articles is intended to do just that. We will carefully consider the truth claims of both Calvinists and Arminians and arrive at some conclusions that may not suit either.1 Our purpose here is not to defend a system, but to understand the truth. The conflicting “isms” in this study (Calvinism and Arminianism) are often considered “sacred cows” and, as a result, seem to be solidified and in need of defense. They have become impediments in the search for truth and “barriers to learn- ing.” Perhaps the emphatic dogmatism and defense of the paradoxical views of Calvinism and Arminianism have impeded the theological search for truth much more than we realize. Bauman reflects, I doubt that theology, as God sees it, entails unresolvable paradox. That is another way of saying that any theology that sees it [paradox] or includes it is mistaken. If God does not see theological endeavor as innately or irremediably paradoxical, 1 For this reason the author declines to be called a Calvinist, a moderate Calvinist, an Arminian, an Augustinian, a Thomist, a Pelagian, or a Semi- Pelagian. -

4 Reformed Orthodoxy

Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology Belt, H. van der Citation Belt, H. van der. (2006, October 4). Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). id7775687 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com 4 Reformed Orthodoxy The period of Reformed orthodoxy extends from the Reformation to the time that liberal theology became predominant in the European churches and universities. During the period the Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican churches were the official churches in Protestant countries and religious polemics between Catholicism and Protestantism formed an integral part of the intense political strife that gave birth to modern Europe. Reformed orthodoxy is usually divided into three periods that represent three different stages; there is no watershed between these periods and it is difficult to “ ” determine exact dates. During the period of early orthodoxy the confessional and doctrinal codifications of Reformed theology took place. This period is characterized by polemics against the Counter-Reformation; it starts with the death of the second- generation Reformers (around 1565) and ends in the first decades of the seventeenth century.1 The international Reformed Synod of Dort (1618-1619) is a useful milestone, 2 “ because this synod codified Reformed soteriology. -

The Nature and Extent of the Atonement in Lutheran

THE N A T U R E A N D E X T E N T O F T H E ATONEMENT I N L U T H E R A N T H E O L O G Y DAVID SCAER, TH.D. I. The Problem The· conflict concerning the nature and extent of the atonement arose in Christian theology because of attempts to reconcile rationally apparently conflicting statements in the Holy Scriptures on the atone- ment and election. Briefly put, passages relating to the atonement are universal in scope including all men and those relating to election apply only to a limited number. Basically there have been three approaches to this tension between a universal atonement and a limited election. One approach is to understand the atonement in light of the election. Since obviously there are many who are not eventually saved, the atonement offered by Christ really applied not to them but only to those who are finally saved, i.e., the elect. This is the Calvinistic or Reformed view. The second approach understands the election in light of the atonement. This view credits each individual with the ability to make a choice of his own free will to believe in Christ. Since Christ died for all men and since man is responsible for his own damnation, therefore he at least cooperates with the Holy Spirit in coming to faith. This is the Arminian or synergistic view, also widely held in Methodism. The third view* is that of classical Lutheran theology. This position as set down in the Formula of Concord (1580) does not attempt to resolve what the Holy Scriptures state con- cerning atonement and election. -

INTEGRITY a Lournøl of Christiøn Thought

INTEGRITY A lournøl of Christiøn Thought PLTBLISHED BY THE COMMISSION FOR THEOLOGICAL INTEGRITY OF THE NAIIONALASSOCIATION OF FREE WILLBAPTISTS Editor Paul V. Harrison Pastoq Cross Timbers Free Will Baptist Church Assistønt Editor Robert E. Picirilli Professor Emeritus, Free Will Baptist Bible College Editorøl Board Tim Eatoru Vice-President, Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College Daryl W Ellis, Pastor, Butterfield Free Wilt Baptist Church, Aurora, Illinois Keith Fletcheq Editor-in-Chief Randall House Publications F. Leroy Forlines, Professor Emeritus, Free Will Baptist Bible College Jeff Manning, Pastor, Unity Free Will Baptist Church, Greenville, North Carolina Garnett Reid, Professo¡, Free Will Baptist Bible College Integrity: A Journøl of Chrístian Thought is published in cooperation with Randall House Publications, Free Will Baptist Bible College, and Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College. It is partially funded by those institutions and a number of interested churches and individuals. Integrity exists to stimulate and provide a forum for Christian scholarship among Free Will Baptists and to fulfill the purposes of the Commission for Theological Integrity. The Commission for Theological Integrity consists of the following members: F. Leroy Forlines (chairman), Dãryl W. Ellis, Paul V. Harisory Jeff Manning, and J. Matthew Pinson. Manuscripts for publication and communications on editorial matters should be directed to the attention of the editor at the following address: 866 Highland Crest Drive, Nashville, Tennessee 37205. E-rnall inquiries should be addressed to: [email protected]. Additional copies of the journal can be requested for $6.00 (cost includes shipping). Typeset by Henrietta Brozon Printed by Randøll House Publications, Nashaille, Tennessee 37217 OCopyright 2003 by the Comrnission for Theological Integrity, National Association of Free Will Baptists Printed in the United States of America Contents Introduction .......7-9 PAULV. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner.KDM\My

The Free Presbyterian Magazine Vol 110 April 2005 No 4 Which Version?1 he shelves of today’s bookshops carry an almost endless variety of Bible Tversions. But how should we assess them? And should we assume that the newer the translation the better? The book under review should give considerable help to those who are asking these and similar questions. In his Preface, Mr Macgregor gives his own experience: “As a young Christian I went to a church that used the Authorised Version (AV). However, on moving with my wife and family to a different area, we went to a church that used the Good News Bible (GNB) and the New International Version (NIV). This enticed me away from the AV for a while. At first these new versions appeared to be easier to read and understand. However, soon I began to notice serious discrepancies (that is, Old Testament references to Christ veiled or missing) in the GNB. This troubled me greatly. I stopped using it, but continued with the NIV, which seemed more reliable. However, as I studied it and compared it with the AV I had first used, I began to feel concerned. The NIV had verses missing, and later I found it had many words missing. Its rendering of some parts gave a completely different meaning. The more I read and compared, the more concerned I became. Also, like the GNB, the NIV was more difficult to commit to memory. I bought a Revised Authorised Version (called in the USA, and now here, the New King James Version (NKJV)). -

Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20Th and 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto ASPECTS OF ARMINIAN SOTERIOLOGY IN METHODIST-LUTHERAN ECUMENICAL DIALOGUES IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY Mikko Satama Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology Department of Systematic Theology Ecumenical Studies 18th January 2009 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO − HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto − Fakultet/Sektion Laitos − Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Systemaattisen teologian laitos Tekijä − Författare Mikko Satama Työn nimi − Arbetets title Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20th and 21st Century Oppiaine − Läroämne Ekumeniikka Työn laji − Arbetets art Aika − Datum Sivumäärä − Sidoantal Pro Gradu -tutkielma 18.1.2009 94 Tiivistelmä − Referat The aim of this thesis is to analyse the key ecumenical dialogues between Methodists and Lutherans from the perspective of Arminian soteriology and Methodist theology in general. The primary research question is defined as: “To what extent do the dialogues under analysis relate to Arminian soteriology?” By seeking an answer to this question, new knowledge is sought on the current soteriological position of the Methodist-Lutheran dialogues, the contemporary Methodist theology and the commonalities between the Lutheran and Arminian understanding of soteriology. This way the soteriological picture of the Methodist-Lutheran discussions is clarified. The dialogues under analysis were selected on the basis of versatility. Firstly, the sole world organisation level dialogue was chosen: The Church – Community of Grace. Additionally, the document World Methodist Council and the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification is analysed as a supporting document. Secondly, a document concerning the discussions between two main-line churches in the United States of America was selected: Confessing Our Faith Together. -

Anglo-Dutch Relations, a Political and Diplomatic Analysis of the Years

1 ANGLO-DUTCH RELATIONS A Political and Diplomatic Analysis of the years 1625-1642 ’’Nations have no permanent friends or allies, they only have permanent interests’’ Lord Palmerston Britain’s Prime Minister 1855 and 1859-65 Anton Poot, M.A. Royal Holloway University of London March 2013 Supervised by Professor Pauline Croft, MA (Oxon) DPhil. FSA FRHistS, to be submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Declaration: I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis, ANGLO-DUTCH RELATIONS A Political and Diplomatic Analysis of the years 1625-1642 is my own. Signed: Name: Anton Poot Date: 2013 For my wife Jesmond 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to analyse Anglo-Dutch relations in this highly volatile period, as perceived and interpreted by both sides, and it also closes the gap between the notable theses of Grayson1 and Groenveld2. On 23 August 1625 Charles I and the Dutch Republic concluded a partnership agreement for joint warfare at sea and a month later a treaty for war against Spain. In December 1625 England, Denmark and the Republic signed treaties to establish the nucleus of an alliance against the Austrian Habsburgs. Charles wanted an active role in continental politics. Also to compel Spain to support his aim to restore his exiled sister Elizabeth and husband Count Elector Frederick V to their Palatinate estates and Frederick to his Electoral dignities in the Empire. The Dutch wanted England as an active partner in their war with Spain. It was a partnership of convenience, with different objectives but with the intention that success would serve the interests of both. -

The Synod of Dort, the Westminster Assembly, and the French Reformed Church, 1618-431 MICHAEL DEWAR

The Synod of Dort, the Westminster Assembly, and the French Reformed Church, 1618-431 MICHAEL DEWAR The European Background In an age of ecumenical councils, from 'Edinburgh, 1910' and 'Amsterdam, 1948' to 'Vatican II', and beyond, it is often forgotten that the Reformers, insular and continental, were no less 'ecumenically' minded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Richard Baxter wrote, 'The Christian world, since the days of the Apostles, had never a Synod of more excellent divines, taking one thing with another, than this [of Westminster] and the Synod of Dort. '2 These were the nearest to the Council of Trent that Protes tantism was to see. Yet earlier correspondence between Geneva and Canterbury shows that closer union might have been possible three generations before. Calvin had written to Cranmer, 'if I can be of any service, I shall not shrink from crossing ten seas, if need be for that object' ,3 (that is, of uniting the Reformed Churches). This was in 1552, the 'high tide' of Anglican Reformation, with Melanchthon and Bull inger for Cranmer's 'Lambeth Confere~e· also. It is tragic that this ideal, so broadly based on international and eirenic lines, came to nothing until Protestantism at home and abroad was hopelessly divided. For it cannot be urged that the 'Dordrace nists' and the Westminster Fathers were other than polemical in their intentions, and divisive in their results. The sixteenth century left the Reformed Churches inclusive and international. The seventeenth century left them enfeebled but embattled, exclusive and nationalistic. The Synod of Dort, 1618 Inevitably Calvinism was closely equated with Netherlands National ism. -

Calvinism #Not Fatalism Calvinism: Argued in Outline

Study guide for Calvinism #not_fatalism Calvinism: Argued in Outline I. CALVINISM B. B. Warfield defines Calvinism as theism and evangelicalism come to their own. That is to say, quite simply, that God saves sinners. He does not merely provide the possibility or opportunity for them to be saved. He does not “do His part” and leave man to do his part to accomplish salvation. No, God actually saves sinners, and that salvation is all of Him. Cornelius Van Til says that Calvinism’s only system is to be open to the Scriptures. He adds, “The doctrines of Calvinism are not deduced in a priori fashion from one major principle such as the sovereignty of God.” This has been one of the most frequent arguments against Calvinism. The charge is that it fastens on to one Scripture principle, God’s sovereignty, and proceeds to develop a logical system based on that principle, with little or no regard to Scripture. As Van Til indicates, such a charge is groundless. Here is a fair statement of the Calvinistic position. We may here note the following Clarifications in particular: 1. The Five Points. What has just been said will make it clear that Calvinism is more than “five points.” The five points were actually answers to five points made by Arminians. Five-point Calvinism is frequently referred to as TULIP theology, using the T-U-L-I-P as an acrostic: Total Depravity; Unconditional Election; Limited Atonement (though Calvinists believe that Arminians, not they, limit the atonement; they prefer such terms as particular redemption or definite atonement); Irresistible Grace; Perseverance of the saints. -

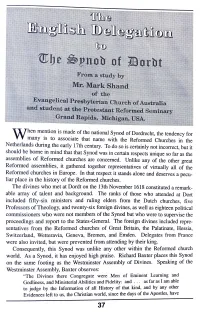

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and .