William B. Hunter Argues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTEGRITY a Lournøl of Christiøn Thought

INTEGRITY A lournøl of Christiøn Thought PLTBLISHED BY THE COMMISSION FOR THEOLOGICAL INTEGRITY OF THE NAIIONALASSOCIATION OF FREE WILLBAPTISTS Editor Paul V. Harrison Pastoq Cross Timbers Free Will Baptist Church Assistønt Editor Robert E. Picirilli Professor Emeritus, Free Will Baptist Bible College Editorøl Board Tim Eatoru Vice-President, Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College Daryl W Ellis, Pastor, Butterfield Free Wilt Baptist Church, Aurora, Illinois Keith Fletcheq Editor-in-Chief Randall House Publications F. Leroy Forlines, Professor Emeritus, Free Will Baptist Bible College Jeff Manning, Pastor, Unity Free Will Baptist Church, Greenville, North Carolina Garnett Reid, Professo¡, Free Will Baptist Bible College Integrity: A Journøl of Chrístian Thought is published in cooperation with Randall House Publications, Free Will Baptist Bible College, and Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College. It is partially funded by those institutions and a number of interested churches and individuals. Integrity exists to stimulate and provide a forum for Christian scholarship among Free Will Baptists and to fulfill the purposes of the Commission for Theological Integrity. The Commission for Theological Integrity consists of the following members: F. Leroy Forlines (chairman), Dãryl W. Ellis, Paul V. Harisory Jeff Manning, and J. Matthew Pinson. Manuscripts for publication and communications on editorial matters should be directed to the attention of the editor at the following address: 866 Highland Crest Drive, Nashville, Tennessee 37205. E-rnall inquiries should be addressed to: [email protected]. Additional copies of the journal can be requested for $6.00 (cost includes shipping). Typeset by Henrietta Brozon Printed by Randøll House Publications, Nashaille, Tennessee 37217 OCopyright 2003 by the Comrnission for Theological Integrity, National Association of Free Will Baptists Printed in the United States of America Contents Introduction .......7-9 PAULV. -

Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20Th and 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto ASPECTS OF ARMINIAN SOTERIOLOGY IN METHODIST-LUTHERAN ECUMENICAL DIALOGUES IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY Mikko Satama Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology Department of Systematic Theology Ecumenical Studies 18th January 2009 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO − HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto − Fakultet/Sektion Laitos − Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Systemaattisen teologian laitos Tekijä − Författare Mikko Satama Työn nimi − Arbetets title Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20th and 21st Century Oppiaine − Läroämne Ekumeniikka Työn laji − Arbetets art Aika − Datum Sivumäärä − Sidoantal Pro Gradu -tutkielma 18.1.2009 94 Tiivistelmä − Referat The aim of this thesis is to analyse the key ecumenical dialogues between Methodists and Lutherans from the perspective of Arminian soteriology and Methodist theology in general. The primary research question is defined as: “To what extent do the dialogues under analysis relate to Arminian soteriology?” By seeking an answer to this question, new knowledge is sought on the current soteriological position of the Methodist-Lutheran dialogues, the contemporary Methodist theology and the commonalities between the Lutheran and Arminian understanding of soteriology. This way the soteriological picture of the Methodist-Lutheran discussions is clarified. The dialogues under analysis were selected on the basis of versatility. Firstly, the sole world organisation level dialogue was chosen: The Church – Community of Grace. Additionally, the document World Methodist Council and the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification is analysed as a supporting document. Secondly, a document concerning the discussions between two main-line churches in the United States of America was selected: Confessing Our Faith Together. -

The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

FALL 2019 volume 6 issue 1 3 FROM RUTHERFORD HALL Dr. Barry J. York 4 FOUR CENTURIES AGO: AN HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE SYNOD OF DORT Dr. David G. Whitla 16 THE FIRST HEADING: DIVINE ELECTION AND REPROBATION Rev. Thomas G. Reid, Jr. 25 THE SECOND HEADING - CHRIST’S DEATH AND HUMAN REDEMPTION THROUGH IT: LIMITED ATONEMENT AT THE SYNOD OF DORDT AND SOME CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGICAL DEBATES Dr. Richard C. Gamble 33 THE THIRD HEADING: HUMAN CORRUPTION Rev. Keith A. Evans 39 THE FOURTH HEADING: “BOTH DELIGHTFUL AND POWERFUL” THE DOCTRINE OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE IN THE CANONS OF DORT Dr. C. J. Williams 47 THE FIFTH HEADING: THE PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS Dr. Barry J. York STUDY UNDER PASTORS The theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary Description Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is provided freely by RPTS faculty and other scholars to encourage the theological growth of the church in the historic, creedal, Reformed faith. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is published biannually online at the RPTS website in html and pdf. Readers are free to use the journal and circulate articles in written, visual, or digital form, but we respectfully request that the content be unaltered and the source be acknowledged by the following statement. “Used by permission. Article first appeared in Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal, the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (rpts.edu).” e d i t o r s General Editor: Senior Editor: Assistant Editor: Contributing Editors: Barry York Richard Gamble Jay Dharan Tom Reid [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] C. -

Justifying Religious Freedom: the Western Tradition

Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition E. Gregory Wallace* Table of Contents I. THESIS: REDISCOVERING THE RELIGIOUS JUSTIFICATIONS FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM.......................................................... 488 II. THE ORIGINS OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN EARLY CHRISTIAN THOUGHT ................................................................................... 495 A. Early Christian Views on Religious Toleration and Freedom.............................................................................. 495 1. Early Christian Teaching on Church and State............. 496 2. Persecution in the Early Roman Empire....................... 499 3. Tertullian’s Call for Religious Freedom ....................... 502 B. Christianity and Religious Freedom in the Constantinian Empire ................................................................................ 504 C. The Rise of Intolerance in Christendom ............................. 510 1. The Beginnings of Christian Intolerance ...................... 510 2. The Causes of Christian Intolerance ............................. 512 D. Opposition to State Persecution in Early Christendom...... 516 E. Augustine’s Theory of Persecution..................................... 518 F. Church-State Boundaries in Early Christendom................ 526 G. Emerging Principles of Religious Freedom........................ 528 III. THE PRESERVATION OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION EUROPE...................................................... 530 A. Persecution and Opposition in the Medieval -

The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip Van Limborch: a Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism

The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip van Limborch: A Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism By John Mark Hicks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Westminster Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy 1985 Faculty Advisor: Dr. Richard C. Gamble Second Faculty Reader: Mr. David W. Clowney Chairman, Field Committee: Dr. D. Claire Davis External Reader: Dr. Carl W. Bangs 2 Dissertation Abstract The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip van Limborch: A Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism By John Mark Hicks The dissertation addresses the problem of the theological relationship between the theology of Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609) and the theology of Philip van Limborch (1633-1712). Arminius is taken as a representative of original Arminianism and Limborch is viewed as a representative of developed Remonstrantism. The problem of the dissertation is the nature of the relationship between Arminianism and Remonstrantism. Some argue that the two systems are the fundamentally the same, others argue that Arminianism logically entails Remonstrantism and others argue that they ought to be radically distinguished. The thesis of the dissertation is that the presuppositions of Arminianism and Remonstrantism are radically different. The thesis is limited to the doctrine of grace. There is no discussion of predestination. Rather, the thesis is based upon four categories of grace: (1) its need; (2) its nature; (3) its ground; and (4) its appropriation. The method of the dissertation is a careful, separate analysis of the two theologians. -

Calvin Theological Seminary Covenant In

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY COVENANT IN CONFLICT: THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CHURCH COVENANT BETWEEN SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND THOMAS HOOKER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY SANG HYUCK AHN GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2011 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan. 49546-4301 800388-6034 Jax: 616957-8621 [email protected] www.calvinserninary.edu This dissertation entitled COVENANT IN CONFLICT: THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CHURCH COVENANT BETWEEN SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND THOMAS HOOKER written by SANG HYUCK AHN and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation ofthe undersigned readers: Carl R Trueman, Ph.D. David M. Rylaarsda h.D. Date Acting Vice President for Academic Affairs Copyright © 2011 by Sang Hyuck Ahn All rights reserved To my Lord, the Head of the Church Soli Deo Gloria! CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 I. Statement of the Thesis 1 II. Statement of the Problem 2 III. Survey of Scholarship 6 IV. Sources and Outline 10 CHAPTER 2. THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE RUTHERFORD-HOOKER DISPUTE ABOUT CHURCH COVENANT 15 I. The Church Covenant in New England 15 1. Definitions 15 1) Church Covenant as a Document 15 2) Church Covenant as a Ceremony 20 3) Church Covenant as a Doctrine 22 2. Secondary Scholarship on the Church Covenant 24 II. Thomas Hooker and New England Congregationalism 31 1. A Short Biography 31 2. Thomas Hooker’s Life and His Congregationalism 33 1) The England Period, 1586-1630 33 2) The Holland Period, 1630-1633: Paget, Forbes, and Ames 34 3) The New England Period, 1633-1647 37 III. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

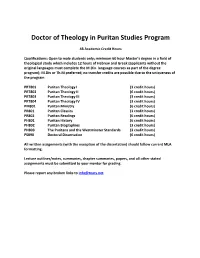

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

William Perkins (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 Pm 1602) Earned a Bachelor’S Plenary Session # 1 Degree in 1581 and a Mas- Dr

MaY 19 (FrIDaY eVeNING) William perkinS (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 pm 1602) earned a bachelor’s plenary Session # 1 degree in 1581 and a mas- Dr. Sinclair Ferguson, ter’s degree in 1584 from WILLIAM William Perkins—A Plain Preacher Christ’s College in Cam- bridge. During those stu- dent years he joined up PERKINS MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY MOrNING) with Laurence Chaderton, CONFereNCe 9:00 - 10:15 am who became his personal plenary Session # 2 tutor and lifelong friend. IN THE ROUND CHURCH Dr. Joel Beeke Perkins and Chaderton met William Perkins’s Largest Case of Conscience with Richard Greenham, Richard Rogers, and others in a spiritual brotherhood 10:30 – 11:45 am at Cambridge that espoused Puritan convictions. plenary Session # 3 Dr. Geoff Thomas From 1584 until his death, Perkins served as lectur- The Pursuit of Godliness in the er, or preacher, at Great St. Andrew’s Church, Cam- Ministry of William Perkins bridge, a most influential pulpit across the street from Christ’s College. He also served as a teaching fellow 12:00 – 6:45 pm at Christ’s College, catechized students at Corpus Free Time Christi College on Thursday afternoons, and worked as a spiritual counselor on Sunday afternoons. In MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY eVeNING) these roles Perkins influenced a generation of young 7:00 – 8:15 pm students, including Richard Sibbes, John Cotton, John plenary Session # 4 Preston, and William Ames. Thomas Goodwin wrote Dr. Stephen Yuille that when he entered Cambridge, six of his instruc- Contending for the Faith: Faith and Love in Perkins’s tors who had sat under Perkins were still passing on Defense of the Protestant Religion his teaching. -

The Role of Wesley in American Methodist Theology Randy L

Methodist History 37 (1999): 71–88 (This .pdf version reproduces pagination of printed form) Respected Founder / Neglected Guide: The Role of Wesley in American Methodist Theology Randy L. Maddox Methodists in North America struggled from nearly the beginning with the question of how they should understand their relationship to John Wesley. There was always a deep appreciation for him as the founder of the movement in which they stood. However there was also a clear hesitance to grant Wesley unquestioned authority on a span of practical and theological issues such as the legitimacy of the American Revolution, the structure for the newly independent Methodist church, and the preferred form for regular Sunday worship. One of the surprising areas where such hesitance about the role of Wesley’s precedent for American Methodist developments emerged was in theology. While Wesley clearly understood himself to be a theologian for his movement, American Methodists increasingly concluded that—whatever his other attributes—Wesley was not a theologian! The purpose of this paper is to investigate the dynamics that led to this revised estimate of Wesley’s status as a theologian and to note the implications that it has had for American Methodist theology. In particular I will consider progressive changes in assumptions about what characterized a theological position or work as “Wesleyan,” when American Methodists acquiesced to the judgment that Wesley himself was not a theologian. I As background to the North American story it is helpful to make clear the sense in which Wesley considered himself a theologian (or a “divine” as eighteenth-century Anglicans were prone to call them).