Increase Mather^S 'Catechismus Logkus^: a Translation and an Analysis of the Role of a Ramist Catechism at Harvard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ramist Style of John Udall: Audience and Pictorial Logic in Puritan Sermon and Controversy

Oral Tradition, 2/1 (1987): 188-213 The Ramist Style of John Udall: Audience and Pictorial Logic in Puritan Sermon and Controversy John G. Rechtien With Wilbur Samuel Howell’s Logic and Rhetoric in England, 1500-1700 (1956), Walter J. Ong’s Ramus, Method, and the Decay of Dialogue (1958) helped establish the common contemporary view that Ramism impoverished logic and rhetoric as arts of communication.1 For example, scholars agree that Ramism neglected audience accomodation; denied truth as an object of rhetoric by reserving it to logic; rejected persuasion about probabilities; and relegated rhetoric to ornamentation.2 Like Richard Hooker in Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity (I.vi.4), these scholars criticize Ramist logic as simplistic. Their objections identify the consequences of Ramus’ visual analogy of logic and rhetoric to “surfaces,” which are “apprehended by sight” and divorced from “voice and hearing” (Ong 1958:280). As a result of his analogy of knowledge and communication to vision rather than to sound, Ramus left rhetoric only two of its fi ve parts, ornamentation (fi gures of speech and tropes) and delivery (voice and gesture). He stripped three parts (inventio, dispositio, and memory) from rhetoric. Traditionally shared by logic and rhetoric, the recovery and derivation of ideas (inventio) and their organization (dispositio) were now reserved to logic. Finally, Ramus’ method of organizing according to dichotomies substituted “mental space” for memory (Ong 1958:280). In the context of this new logic and the rhetoric dependent on it, a statement was not recognized as a part of a conversation, but appeared to stand alone as a speech event fi xed in space. -

Antoine De Chandieu (1534-1591): One of the Fathers Of

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): ONE OF THE FATHERS OF REFORMED SCHOLASTICISM? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2013 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan • 49546-4301 800388-6034 fax: 616 957-8621 [email protected] www. calvinseminary. edu. This dissertation entitled ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): L'UN DES PERES DE LA SCHOLASTIQUE REFORMEE? written by THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: Richard A. Muller, Ph.D. I Date ~ 4 ,,?tJ/3 Dean of Academic Programs Copyright © 2013 by Theodore G. (Ted) Van Raalte All rights reserved For Christine CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1 Introduction: Historiography and Scholastic Method Introduction .............................................................................................................1 State of Research on Chandieu ...............................................................................6 Published Research on Chandieu’s Contemporary -

1 the Summa Theologiae and the Reformed Traditions Christoph Schwöbel 1. Luther and Thomas Aquinas

The Summa Theologiae and the Reformed Traditions Christoph Schwöbel 1. Luther and Thomas Aquinas: A Conflict over Authority? On 10 December 1520 at the Elster Gate of Wittenberg, Martin Luther burned his copy of the papal bull Exsurge domine, issued by pope Leo X on 15 June of that year, demanding of Luther to retract 41 errors from his writings. The time for Luther to react obediently within 60 days had expired on that date. The book burning was a response to the burning of Luther’s works which his adversary Johannes Eck had staged in a number of cities. Johann Agricola, Luther’s student and president of the Paedagogium of the University, who had organized the event at the Elster Gate, also got hold of a copy of the books of canon law which was similarly committed to the flames. Following contemporary testimonies it is probable that Agricola had also tried to collect copies of works of scholastic theology for the burning, most notably the Summa Theologiae. However, the search proved unsuccessful and the Summa was not burned alongside the papal bull since the Wittenberg theologians – Martin Luther arguably among them – did not want to relinquish their copies.1 The event seems paradigmatic of the attitude of the early Protestant Reformers to the Summa and its author. In Luther’s writings we find relatively frequent references to Thomas Aquinas, although not exact quotations.2 With regard to the person of Thomas Luther could gleefully report on the girth of Thomas Aquinas, including the much-repeated story that he could eat a whole goose in one go and that a hole had to be cut into his table to allow him to sit at the table at all.3 At the same time Luther could also relate several times and in different contexts in his table talks how Thomas at the time of his death experienced such grave spiritual temptations that he could not hold out against the devil until he confounded him by embracing his Bible, saying: “I believe what is written in this book.”4 At least on some occasions Luther 1 Cf. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

Ramism, Rhetoric and Reform an Intellectual Biography of Johan Skytte (1577–1645)

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Uppsala Studies in History of Ideas 42 Cover: Johan Skytte af Duderhof (1577–1645). Oil painting by Jan Kloppert (1670–1734). Uppsala universitets konstsamling. Jenny Ingemarsdotter Ramism, Rhetoric and Reform An Intellectual Biography of Johan Skytte (1577–1645) Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Auditorium Minus, Gustavianum, Akademigatan 3, Uppsala, Saturday, May 28, 2011 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in Swedish. Abstract Ingemarsdotter, J. 2011. Ramism, Rhetoric and Reform. An Intellectual Biography of Johan Skytte (1577–1645). Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Uppsala Studies in History of Ideas 42. 322 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-8071-4. This thesis is an intellectual biography of the Swedish statesman Johan Skytte (1577–1645), focusing on his educational ideals and his contributions to educational reform in the early Swedish Age of Greatness. Although born a commoner, Skytte rose to be one of the most powerful men in Sweden in the first half of the seventeenth century, serving three generations of regents. As a royal preceptor and subsequently a university chancellor, Skytte appears as an early educational politician at a time when the Swedish Vasa dynasty initiated a number of far-reaching reforms, including the revival of Sweden’s only university at the time (in Uppsala). The contextual approach of the thesis shows how Skytte’s educational reform agenda was shaped by nationally motivated arguments as well as by a Late Renaissance humanist heritage, celebrating education as the foundation of all prosperous civilizations. Utilizing a largely unexplored source material written mostly in Latin, the thesis analyzes how Skytte’s educational arguments were formed already at the University of Marburg in the 1590s, where he learned to embrace the utility-orientated ideals of the French humanist Petrus Ramus (1515–1572). -

Metaphysical Poetry Characteristics Pdf

Metaphysical poetry characteristics pdf Continue Welcome to Literature Heaven. The name is later attributed to the singers who dealt with questions regarding the abstract in concrete terms. They use logic to explain the inexplicable. Literally, metaphysical means to go beyond physical or specific. - is often used in the sense that we are talking about inconsequential and supernatural things - abstract, not physical. The era objects to the heroic and the sublime, and it objects to the simplification and separation of mental abilities. Metaphysical poetry was the product of popularization of the study of psychic phenomena. Ethics, overshadowed by psychology, we accept the belief that any state of mind is extremely complex, and mostly consists of chances and ends in a constant stream of manipulated desire and fear. Neither fiction nor cynical nor sensual occupies excessive significance with Donn; elements in his mind was order and congruence. The range of his feelings was great, but no more remarkable than his unity. He was generally present in every thought and in every sense. What is true for his mind is true, from another point of view, of his language and versification. Style, rhythm, to be significant, must embody a significant mind, must be produced the need for a new form for new content. T.S. Eliot. Maybe just a little pointless literary jargon. Characteristics: Intellectually strict, simple, dialectical, subtle. Argumentatively - using logic, sillogisms or paradox in persuasion. Concentrated complex and difficult thought Is Dramatic, with a sharp aggressive opening, but modulating tones. Style is a laconic, laconic, epigrammatic use of vanity; banal medieval themes with many comparisons with unusual, unexpected things or images called vanities or extended metaphors. -

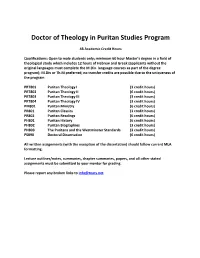

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Artificial Memory Systems and Early Modern England

‘Must I Remember?’ Artificial Memory Systems and Early Modern England Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Jonathan Joseph Michael Day. June 2014 Abstract My thesis traces the evolution of artificial memory systems from classical Greece to early modern England to explore memorial traumas and the complex nature of a very particular way of remembering. An artificial memory system is a methodology to improve natural memory. Classical artificial memory systems employ an architectural metaphor, emphasising regularity and striking imagery. Classical memory systems also frequently describe the memory as a blank page. This thesis follows the path of transmission of these ideas and the perennial relationship between memory and forgetting and memory and fiction, as well as the constant threat of memorial collapse. ii Contents Introduction: 1–6 Chapter One: 7–39 Creation and Destruction: Simonides and the Classical Art of Memory Chapter Two: 40–65 Neoplatonism: Memory, Forgetting and Theatres Chapter Three: 66–96 Medieval Memory: Dreams of Texts Chapter Four: 97–129 Cicero in the Early Modern School: Grammar, Rhetoric and Memory Chapter Five: 130–161 Traumas of Memory: The English Reformation Chapter Six: The 162–193 Materials of Early Modern Memory Chapter Seven: 194–224 Hamlet; ‘Rights of Memory’ and ‘Rites of Memory’ Coda 225–231 Figures: 232–238 Bibliography 239–256 iii List of Figures Figure 1. Ramon Lull, Ars Brevis ([Montpellier (?)], 1308), cited in Doctor Illuminatus: A Ramon Lull Reader, ed. by Anthony Bonner (Chichester: Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 300. Figure 2. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

Directions in the Study of Early Modern Reformed Thought

Perichoresis Volume 14. Issue 3 (2016): 3-16 DOI: 10.1515/perc-2016-0013 DIRECTIONS IN THE STUDY OF EARLY MODERN REFORMED THOUGHT RICHARD A. MULLER * Calvin Theological Seminary ABSTRACT. Given both the advances in understanding of early modern Reformed theology made in the last thirty years, the massive multiplication of available sources, the significant liter- ature that has appeared in collateral fields, there is a series of highly promising directions for further study. These include archival research into the life, work, and interrelationships of var- ious thinkers, contextual examination of larger numbers of thinkers, study of academic faculties, the interrelationships between theology, philosophy, science, and law, and the interactions pos- itive as well as negative between different confessionalities. KEY WORDS: Reformed orthodoxy, post-Reformation Reformed thought, early modernity, ex- egesis, philosophy Recent Advances in Research The study of early modern Reformed thought has altered dramatically in the last several decades. The once dominant picture of Calvin as the prime mover of the Reformed tradition and sole index to its theological integrity has largely disappeared from view, as has the coordinate view of ‘Calvinism ’ as a monolithic theology and the worry over whether later Reformed thought re- mained ‘true ’ to Calvin. The relatively neglected field of seventeenth-century Reformed thought has expanded and developed both in the number of di- verse thinkers examined and in the variety of approaches to the materials. (Given the number of recent published studies of early modern Reformed thought, the following essay makes no attempt to offer a full bibliography, but only to provide examples of various types of research. -

William Perkins (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 Pm 1602) Earned a Bachelor’S Plenary Session # 1 Degree in 1581 and a Mas- Dr

MaY 19 (FrIDaY eVeNING) William perkinS (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 pm 1602) earned a bachelor’s plenary Session # 1 degree in 1581 and a mas- Dr. Sinclair Ferguson, ter’s degree in 1584 from WILLIAM William Perkins—A Plain Preacher Christ’s College in Cam- bridge. During those stu- dent years he joined up PERKINS MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY MOrNING) with Laurence Chaderton, CONFereNCe 9:00 - 10:15 am who became his personal plenary Session # 2 tutor and lifelong friend. IN THE ROUND CHURCH Dr. Joel Beeke Perkins and Chaderton met William Perkins’s Largest Case of Conscience with Richard Greenham, Richard Rogers, and others in a spiritual brotherhood 10:30 – 11:45 am at Cambridge that espoused Puritan convictions. plenary Session # 3 Dr. Geoff Thomas From 1584 until his death, Perkins served as lectur- The Pursuit of Godliness in the er, or preacher, at Great St. Andrew’s Church, Cam- Ministry of William Perkins bridge, a most influential pulpit across the street from Christ’s College. He also served as a teaching fellow 12:00 – 6:45 pm at Christ’s College, catechized students at Corpus Free Time Christi College on Thursday afternoons, and worked as a spiritual counselor on Sunday afternoons. In MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY eVeNING) these roles Perkins influenced a generation of young 7:00 – 8:15 pm students, including Richard Sibbes, John Cotton, John plenary Session # 4 Preston, and William Ames. Thomas Goodwin wrote Dr. Stephen Yuille that when he entered Cambridge, six of his instruc- Contending for the Faith: Faith and Love in Perkins’s tors who had sat under Perkins were still passing on Defense of the Protestant Religion his teaching.