World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Establishing a Holocene Tephrochronology for Western Samoa and Its Implication for the Re-Evaluation of Volcanic Hazards

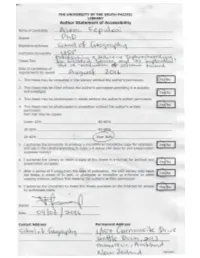

ESTABLISHING A HOLOCENE TEPHROCHRONOLOGY FOR WESTERN SAMOA AND ITS IMPLICATION FOR THE RE-EVALUATION OF VOLCANIC HAZARDS by Aleni Fepuleai A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright © 2016 by Aleni Fepuleai School of Geography, Earth Science and Environment Faculty of Science, Technology and Environment The University of the South Pacific August 2016 DECLARATION Statement by Author I, Aleni Fepuleai, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledge is made in the next. Signature: Date: 01/07/15 Name: Aleni Fepuleai Student ID: s11075361 Statement by Supervisor The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mr Aleni Fepuleai. Signature Date: 01/07/15 Name: Dr Eleanor John Designation: Principal Supervisor ABSTRACT Samoan volcanism is tectonically controlled and is generated by tension-stress activities associated with the sharp bend in the Pacific Plate (Northern Terminus) at the Tonga Trench. The Samoan island chain dominated by a mixture of shield and post-erosional volcanism activities. The closed basin structures of volcanoes such as the Crater Lake Lanoto enable the entrapment and retention of a near-complete sedimentary record, itself recording its eruptive history. Crater Lanoto is characterised as a compound monogenetic and short-term volcano. A high proportion of primary tephra components were found in a core extracted from Crater Lake Lanoto show that Crater Lanoto erupted four times (tephra bed-1, 2, 3, and 4). -

Samoa Socio-Economic Atlas 2011

SAMOA SOCIO-ECONOMIC ATLAS 2011 Copyright (c) Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS) 2011 CONTACTS Telephone: (685) 62000/21373 Samoa Socio Economic ATLAS 2011 Facsimile: (685) 24675 Email: [email protected] by Website: www.sbs.gov.ws Postal Address: Samoa Bureau of Statistics The Census-Surveys and Demography Division of Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS) PO BOX 1151 Apia Samoa National University of Samoa Library CIP entry Samoa socio economic ATLAS 2011 / by The Census-Surveys and Demography Division of Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS). -- Apia, Samoa : Samoa Bureau of Statistics, Government of Samoa, 2011. 76 p. : ill. ; 29 cm. Disclaimer: This publication is a product of the Division of Census-Surveys & Demography, ISBN 978 982 9003 66 9 Samoa Bureau of Statistics. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions 1. Census districts – Samoa – maps. 2. Election districts – Samoa – expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of any funding or census. 3. Election districts – Samoa – statistics. 4. Samoa – census. technical agencies involved in the census. The boundaries and other information I. Census-Surveys and Demography Division of SBS. shown on the maps are only imaginary census boundaries but do not imply any legal status of traditional village and district boundaries. Sam 912.9614 Sam DDC 22. Published by The Samoa Bureau of Statistics, Govt. of Samoa, Apia, Samoa, 2015. Overview Map SAMOA 1 Table of Contents Map 3.4: Tertiary level qualification (Post-secondary certificate, diploma, Overview Map ................................................................................................... 1 degree/higher) by district, 2011 ................................................................... 26 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 3 Map 3.5: Population 15 years and over with knowledge in traditional tattooing by district, 2011 ........................................................................... -

Aufaigaluega Ofisa I Lalovaea: 1

FAATULAGAGA AUFAIGALUEGA MISIONA SAMOA & TOKELAU MO LE 2021: AUFAIGALUEGA OFISA I LALOVAEA: 1. Pr Sione Ausage Peresetene, Galuega a Faifeau, Tausimea, Saolotoga o Tapuaiga, Faatonu Faatutuina Lotu Fou 2. Pr Neru Nuuialii Failautusi, Faatonu Auaunaga mo Aiga, Fesootaiga, TV & Leitio, Faamautuina o Fanua & Eleele o le Ekalesia 3. Mr Benjamin Tofilau Teutupe, Faatonu Soifua Maloloina, Meatotino Ekalesia, Atinae ma Faatoaga o le Ekalesia 4. Pr Tino Okesene Faatonu Autalavou, Kalapu Suela & Kalapu Suesueala 5. Pr David Afamasaga Faatonu Aoga Sapati & Galuega Faamisionare 6. Mrs Pelenatete Siaki Faatonu Tinā & Tamaitai & Aoga Sapati Fanau 7. Mrs Su”a Julia Wallwork Faatonu ADRA Samoa 8. Mrs I’o Lindsay Faatonu Fale Tusi & Fale Lomitusi 9. Mrs Soonafai Toeaso Faatonu Evagelia o Lomiga & Taitai Talosaga Misiona 10. __________________ Failautusi Taitaiga, Fesootaiga, Ofisa Femalagaiga 11. Peleiupu Key Failautusi o Matagaluega & Tali Telefoni 12. Maryanne Suisala Tausi Tusi Sinia & Fesoasoani Fale Tusi 13. Emmanuel Kalau Tausi Tusi Lagolago & IT 14. _________________ Tausi Tusi Lagolago 15. Mizpa Soloa Tali Tupe UPOLU – FAIFEAU MO EKALESIA: SUAFA NUU/EKALESIA 1. Pr Olive Tivalu Dean Apia, Taitai Motu Upolu, Faaliliu & Pepa o le Tala Moni 2. Bro Evander Tuaifaiva Immanuel, Faifeau Aoga SAC & Faifeau TV 3. Pr David Afamasaga Vaitele-uta & Vaitele-fou 4. Pr Tino Okesene Alafua & Vaiusu 5. Pr Taei Siaki Siusega, Falelauniu & Nuu 6. Pr Neru Nuuialii Tiapapata 7. Pr Sione Ausage Magiagi 8. Pr. Mose Hurrell Vailele, Laulii, Fagalii 9. Pr Orion Savea Vailoa & Fusi 10. Bro Esera Luteru Saleaaumua & Aufaga 11. Pr Sagele Moi Tipasa Kosena, Saleapaga & Faifeau mo Faatalaiga 12. Pr Lasi Nai Sapunaoa & Togitogiga 13. -

Sāmoa’S Development As a ‘Nation’

Folauga mo A’oa’oga: Migration for education and its impact on Sāmoa’s development as a ‘nation’ The stories of 18 Samoan research participants who migrated for education, and the impact their journeys have made on the development of Sāmoa. BY Avataeao Junior Ulu A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2018 Acknowledgements E mamalu oe le Ali’i, maualuga le mea e te afio ai. Ia fa’ane’ene’eina oe le tolu tasi paia. O oe o le Atua fai vavega, le Atua o fa’amalologa, le Atua tali mana’o. Fa’afetai mo lau ta’ita’iga i lenei folauga. Ia fa’aaogaina lo’u tagata e fa’alauteleina ai lou Suafa mamana i le lalolagi. This research would not have been possible without the contributions of my 18 research participants: Aloali’i Viliamu, Aida Sāvea, Cam Wendt, Falefata Hele Ei Matatia & Phillippa Te Hira - Matatia, HE Hinauri Petana, Honiara Salanoa (aka Queen Victoria), Ps Latu Sauluitoga Kupa & Ps Temukisa Kupa, Ps Laumata Pauline Mulitalo, Maiava Iosefa Maiava & Aopapa Maiava, Malae Aloali’i, Papali’i Momoe Malietoa – von Reiche, Nynette Sass, Onosefulu Fuata’i, Sa’ilele Pomare, and Saui’a Dr Louise Marie Tuiomanuolo Mataia-Milo. Each of your respective stories of the challenges you faced while undertaking studies abroad is inspirational. I am humbled that you entrusted me with these rich stories and the generosity with your time. Sāmoa as a ‘nation’ is stronger because of you, continue doing great things for the pearl of Polynesia. -

WT/TPR/S/386/Rev.1 21 June 2019 (19-4218) Page

WT/TPR/S/386/Rev.1 21 June 2019 (19-4218) Page: 1/83 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT SAMOA Revision This report, prepared for the first Trade Policy Review of Samoa, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from Samoa on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Masahiro Hayafuji (Tel: 022 739 5873); Thomas Friedheim (Tel: 022 739 5083) and Michael Kolie (Tel: 022 739 5931). Document WT/TPR/G/386 contains the policy statement submitted by Samoa. Note: This report was drafted in English. WT/TPR/S/386/Rev.1 • Samoa - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 6 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ....................................................................................... 10 1.1 Main Features of the Economy ................................................................................... 10 1.2 Recent Economic Developments ................................................................................. 12 1.3 Developments in Trade and Investment ...................................................................... 15 1.3.1 Trends and patterns in merchandise and services trade ............................................. -

The Case of Samoa

GeoHazards Article Multiscale Quantification of Tsunami Hazard Exposure in a Pacific Small Island Developing State: The Case of Samoa Shaun Williams 1,* , Ryan Paulik 1 , Rebecca Weaving 2,3, Cyprien Bosserelle 1 , Josephina Chan Ting 4, Kieron Wall 1 , Titimanu Simi 5 and Finn Scheele 6 1 National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), Christchurch 8011, New Zealand; [email protected] (R.P.); [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (K.W.) 2 School of Geography, Environment and Geosciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire PO1 2UP, UK; [email protected] 3 Ascot Underwriting Ltd., London EC3M 3BY, UK 4 Disaster Management Office, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Apia WS1339, Western Samoa; [email protected] 5 Project Unit, Samoa Green Climate Fund Project, Ministry of Finance, Apia WS1339, Western Samoa; [email protected] 6 GNS Science, Lower Hutt 5011, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study presents a scenario-based approach for identifying and comparing tsunami exposure across different sociopolitical scales. In Samoa, a country with a high threat to local tsunamis, we apply scenarios for the 2009 South Pacific tsunami inundation at different grid resolutions (50 and 10 m) to quantify building and road exposure at the national, district and village levels. We Citation: Williams, S.; Paulik, R.; show that while the coarser 50 m model is adequate for use in the rapid identification of exposure Weaving, R.; Bosserelle, C.; Chan at the national and district levels, it can overestimate exposure by up to three times more at the Ting, J.; Wall, K.; Simi, T.; Scheele, F. -

O Le Fa'afanua O Le Itumalo O Lepā I

NUMERA O LE PUSAMELI-1151 NUMERA O LE TELEFONI Fogafale 1 & 2 FMFM II, (685)62000/21373 Matagialalua NUMERA O LE FAX (685)24675 MAOTA O LE MALO [email protected] APIA Upega tafailagi-www.sbs.gov.ws SAMOA O le fa’afanua o le Itumalo o Lepā i totonu o Upolu FA’AMAUMAUGA MA FA’AMATALAGA O LE ITUMALO O LEPĀ 17 Tesema, 2018 Fa’amaumauga ma Fa’amatalaga o le Itumalo o Lepa 1 Fa’amaumauga ma Fa’amatalaga o le Itumalo o Lepa 2 FA’ATOMUAGA O le līpoti muamua lenei ua tu’ufa’atasia ai nisi o fa’amatalaga ma fa’amaumauga ua filifilia mo Itumalo e 47 i totonu o Sāmoa. O nei fa’amaumauga na mafai ona aoina mai le Tusigāigoa o Tagata ma Fale 2016. O fa’amatalaga olo’o i totonu o lenei līpoti e aofia ai le Vaega 1: Fa’amaumauga i le Faitau Aofa’i o tagata e pei ona taua i lalo Faitau aofa’i o tagata mai tusigāigoa e fā talu ai, Fa’amaumauga o ali’i ma tama’ita’i, Tausaga o tagata, Tulaga tau a’oa’oga, Galuega fa’atino ma Tulaga Tau Tapuaiga. Vaega 2: Fa’amaumauga o Auāiga ma au’au’naga na ‘ausia e pei ona tāua atu i lalo Aofa’iga o Auāiga, Auaunaga o moli eletise, Auaunaga o suāvai, Fa’avelaina o mea’ai taumafa, Auāiga ua maua pusa ‘aisa Feso’ota’iga i telefoni, leitiō ma televise Auāiga ua maua ta’avale afi Auaunaga o lapisi lafoa’i Ituaiga faleui Vaega 3: Siata mo fa’amaumauga o afio’aga ta’itasi i totonu o Itumalo Vaega 4: Pepa fesili o le Tusigaigoa o Tagata ma Fale 2016 Fa’amoemoe o lea aoga lenei līpoti mo le atina’e o Itumalo ma afioaga uma o le atunu’u. -

Samoa Tourism Sector Plan 2014

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 SECTION 2. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 2 • Government Development Policy • Review of STDP 2009 - 13 • STSP Development Process SECTION 3. SITUATION ANALYSIS ........................................................................................ 4 • Samoa and Sustainable Tourism • The Economic Value of Tourism • The Tourism Market • Cruise Sector Tourism • Tourism Supply and Products • Growth Prospects • Visitor Targets • Tourism Institutional Context SECTION 4. STRATEGIC DIRECTION, GOALS AND OBJECTIVES .............................................19 • Tourism Sector Vision • Development Principles • Strategic Policy Outcomes and Goals • Tourism Sector Indicators SECTION 5. SECTOR CONSTRAINTS, KEY STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS ..................................22 • Introduction • Marketing and Research • Investment and Business Enabling Environment • Product Development • HRD and Training • Infrastructure and Access SECTION 6. IMPLEMENTATION STRUCTURE ......................................................................63 • Tourism Sector Management and Coordinating Mechanisms SECTION 7. MONITORING AND EVALUATION ....................................................................66 • Logframe and STSP Action Plans • Performance and Monitoring • Tourism Forum and Annual Review • CDC Progress Report -

BUS and TAXI FARE RATE Faamamaluina : 28 Aperila 2014 Effective : 28Th April 2014

TOTOGI FAAPOLOAIGA O PASESE O PASI MA TAAVALE LAITI LA’UPASESE BUS AND TAXI FARE RATE Faamamaluina : 28 Aperila 2014 Effective : 28th April 2014 PULEGA O FELAUAIGA I LE LAUELEELE LAND TRANSPORT AUTHORITY TOTOGI O PASESE O PASI LAUPASESE UPOLU MA SAVAII TULAFONO FAAPOLOAIGA O TAAVALE AFI 2014 FAAMAMALUINA 28 APERILA 2014 PASSENGER FARE RATES FOR MOTOROMNIBUSES UPOLU AND SAVAII ROAD TRAFFIC ORDER 2014 EFFECTIVE 28 APRIL 2014 E tusa ai ma le Tulafono Autu o Taavale Afi 1960 i fuaiaupu vaega “73”, o le Komiti Faatonu o le Pulega o Felauaiga i le Laueleele faatasi ai ma le ioega a le Afioga i le Minisita o le Pulega o Felauaiga i le Laueleele e faapea; Ua Faasilasila Aloaia Atu Nei,o le totogi o pasese aupito maualuga mo malaga uma a pasi laupasese ua laisene mo femalagaina i Upolu ma Savaii, o le a taua i lalo. [Pursuant to the Road Traffic Ordinance 1960,section “73” requirements that the Land Transport Authority Board of Directors within the concur- rence of the Honourable Minister of Land Transport Authority, Do hereby Declare that the following maximum fares scale rates shall to be charged in respect of passenger transportation in motor omnibuses in Upolu and Savaii.] UPOLU Amata mai le Fale Faatali pasi i Sogi/Siitaga o totogi o Pasese[15%] [Sogi Bus Terminal Towards and fare increased 15%] SAVAII Amata mai le Uafu i Salelologa, Siitaga o totogi o Pasese [15%] [Salelologa Wharf towards and fare increase 15] SIITAGA O PASESE O PASI 15% UPOLU 2014 15% BUS FARE INCREASE - UPOLU 2014 Eastern Cost (Itumalo I Sasae) from Sogi Bus Terminal. -

Early Childhood Development in Samoa Baseline Results from the Samoan Early Human Capability Index

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT IN SAMOA BASELINE RESULTS FROM THE SAMOAN EARLY HUMAN CAPABILITY INDEX Sally Brinkman Alanna Sincovich Public Disclosure Authorized Binh Thanh Vu 2017 EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT IN SAMOA BASELINE RESULTS FROM THE SAMOAN EARLY HUMAN CAPABILITY INDEX Sally Brinkman Alanna Sincovich Binh Thanh Vu 2017 Report No: AUS0000129 © 2017 The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: “World Bank. 2017. Early Childhood Development in Samoa: Baseline results from the Samoan Early Human Capability Index. © World Bank.” All queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. -

Community Integrated Management Plan Implementation Guidelines

Fuafuaga mo le Si’itia o le Malupuipuia o Nu’u ma Afio’aga mai Suiga o le Tau Itumalo Lepa Ta’iala o Galuega 2018 COMMUNITY INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PLAN IMPLEMENTATION GUIDELINES ‘Upu Tomua E iā te a'u le ava tele e fa’ailoa atu ai Fuafuaga mo le Siitia o le Malupuipuia o Nuu ma Afioaga mai Suiga o le Tau (Fuafuaga o le CIM) lea sā uluai fa’aigoaina o Fuafuaga mo le Vaaia Lelei o Aseta Tulata i le Sami. ‘O le toe iloiloina o nei fuafuaga na suia ai le faatinoina talu le uluai seti o fuafuaga na tapenaina mo itumalo e 15 i le tausaga 2002 – 2003 i lalo o le polokalame na faatupeina e le Faletupe o le Lalolagi ma le 26 itumalo mulimuli na faamaeaina i le tausaga 2004-2007 i le polokalame a Samoa mo le Vaaia lelei o Aseta Tulata i le Samoa na faatupeina e le Faletupe o le Lalolagi. O le taimi nei ua lautele atu le fa’ata’atiaga o le polokalame ua iai nei ma ua aofia le atunuu atoa mai i tuasivi se’ia o’o i le ā'au (ridge to reef approach). Ua le gata i atinae tetele ae ua aofia nei totonu ma le siosiomaga ma punaoa faalenatura ae fapea foi ma alamanuia mo nuu ma afioaga aemaise a latou pulega lelei. O le Taiala o le CIM lea na afua mai ai fuafuaga o le CIM(CIM Plan) na toe teuteuina ia Aukuso 2015 ‘ina ‘ia atagia ai le faataatiaga fou mo le faatinoina o lenei fuafuaga e le Malo ma ua iai le fuafuaga o le a faatinoina nei CIM I le vaitau e tai 10 tausaga ma toe iloilo nai lo le 5 tausaga na uluai fuafuaina ai. -

TSUNAMI Samoa, 29 September, 2009

TSUNAMI Samoa, 29 September, 2009 Sunset Lalomanu Beach 2009 An account of the tsunami disaster, the response, its aftermath, acknowledgement and the trek to recovery. Prepared by: The Government of Samoa 1 NOTE! This is not intended to be a comprehensive account of the tsunami disaster. Such an account would require more in depth research, interviews with victims and survivors as well as aid and relief workers and volunteers, both public and private, in order to do justice to such a task and to the memory of those who lost their lives, those who survived, and those who worked tirelessly and selflessly to try to alleviate the suffering of the thousands of people affected. The tsunami was well covered and documented by the media and hopefully those records shall suffice to preserve the story of this disaster for posterity. This therefore is only an overview of the disaster, the response to it and the coordination role of the Government through the National Disaster Management Council, and the implementation of the Recovery Plan. Above all, this is the best opportunity to publicly acknowledge all that was given so willingly and generously for Samoa and its people in probably its darkest moments in history. 2 Faafetai! Thank You! In addition to all messages of gratitude and appreciation we had conveyed either publicly or privately and individually in the past, this report serves to iterate acknowledgement of the contributions of governments, International organizations, non government organizations, private sector, as well as individuals, both in Samoa and abroad, rendered in so many different ways, towards the relief and recovery operations in the wake of the earthquake and tsunami which hit Samoa in late September 2009.