Inventory of Language Certification in Europe a Report to the European

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unaided Awareness of Language & Cultural Centers

Awareness, Attitudes & Usage Study 2018 Baseline Wave Étude sur la Notoriété de la Marque: L’Alliance Française de Chicago. - 1 Background information Last year’s presentation: ❑ Summarized about 4 years of research: ◆ Student satisfaction surveys. ◆ Focus groups: web site & brochure. ◆ Simmons data: activity profiles for target consumers. ◆ Student engagement survey. ❑ Results: ◆ New, smaller brochure ◆ New, responsive website ◆ Advertising on public transportation (CTA Red Line) ◆ Advertising on the building ◆ Importance of cell phones! - 2 Where we are today: The new responsive AF-Chicago website AF-Chicago 2018 Marketing Program 22-Jan-18 - 3 This year… AA&U Study - measures: ❑ Brand awareness. ❑ Attitudes about the brand. ❑ Usage (patronage). Purpose: ❑ Assess effectiveness of marketing campaign (over time)… ❑ Increase brand awareness? ❑ Improve attitudes & usage? Frequency: ❑ Usually once a year; ❑ More often if there is a major expenditure in marketing. - 4 Survey sample characteristics Our sample composition: ❑ 999 respondents ❑ Residents of “Greater Chicago Metro Area” ◆ Counties immediately surrounding Chicago & Cook County. ◆ Including Lake & Porter in NW Indiana. ◆ Excluding Lake and Gundy in IL. ❑ Roughly even balance of men and women. ❑ Age range: 25-75. ❑ Education: HS Diploma + ❑ Income: $50k+ annual HHI. - 5 Why the large sample? 999 Respondents… ❑ We anticipated that our target group would be small. ❑ Need a large sample to find them in sufficient numbers to obtain reliable descriptive statistics. - 6 Brand Awareness – Notoriété de la Marque • Unaided Brand Awareness • Aided Brand Awareness - 7 Why is “unaided brand awareness” important? Direct correlation with market dominance ❑ “Unaided brand awareness” is the key predictor of market dominance. ❑ The top three brands in almost any category are those that are recalled immediately and spontaneously by the members of the target audience. -

“Proyecto Conectados Y Seguros”: Una Nueva Línea De Trabajo En La RBIC

IX JORNADA PROFESIONAL DE LA RED DE BIBLIOTECAS DEL INSTITUTO CERVANTES: Bibliotecas y empoderamiento digital. MADRID, 14 de diciembre 2016 “Proyecto Conectados y seguros”: una nueva línea de trabajo en la RBIC. Ana Roca Gadea1 (Instituto Cervantes) Spanish abstract Consideradas por los ciudadanos como lugares seguros y confiables, las bibliotecas no cesan de ampliar el rol que desempeñan en el seno de sus comunidades. Fomentar el empoderamiento digital (la capacidad de utilizar la tecnología para introducir cambios positivos en las vidas de personas y colectivos) se ha convertido en un aspecto central dentro de la labor de las bibliotecas de apoyar la educación a lo largo de la vida. La biblioteca del Instituto Cervantes de Atenas organizó entre 2013 y 2016 algunas iniciativas de capacitación digital, entre ellas, el Proyecto Conectados y Seguros, en colaboración con la Fundación Cibervoluntarios. La Red de Bibliotecas Cervantes se enfrenta actualmente al reto de integrar esta línea de trabajo en el seno de su principal ámbito de actuación, esto es, con la difusión de la lengua y la cultura de los países de habla española. English abstratc Considered by citizens as trusted and safe places, libraries are continuously widening their role within their communities. Promoting digital empowerment (the capacity of using technology to introduce positive changes in the lives of individuals and groups) has become a key aspect in libraries’ role in supporting life-long learning. Between 2013 and 2016, the Instituto Cervantes Library in Athens organized several digital training iniciatives, such as “Safe and Connected Project”, in collaboration with Cibervoluntarios Foundation. Nowadays the Network of Instituto Cervantes Libraries faces the challenge of integrating this line of work within its main course of action, that is the promotion of the language and culture of Spanish speaking countries. -

External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish

東京外国語大学論集 第 100 号(2020) TOKYO UNIVERSITY OF FOREIGN STUDIES, AREA AND CULTURE STUDIES 100 (2020) 43 External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish 「少数言語」の対外普及 ̶̶ バスク語とカタルーニャ語 の事例をスペイン語の事例と比較しつつ HAGIO Sho W o r l d L a n g u a g e a n d S o c i e t y E d u c a t i o n C e n t r e , T o k y o U n i v e r s i t y o f F o r e i g n S t u d i e s 萩尾 生 東京外国語大学 世界言語社会教育センター 1. The Historical Background of Language Dissemina on Overseas 2. Theore cal Frameworks 2.1. Implemen ng the Basis of External Diff usion 2.2. Demarca on of “Internal” and “External” 2.3. The Mo ves and Aims of External Projec on of a Language 3. The Case of Spain 3.1. The Overall View of Language Policy in Spain 3.2. The Cervantes Ins tute 3.3. The Ramon Llull Ins tute 3.4. The Etxepare Basque Ins tute 4. Transforma on of Discourse 4.1. The Ra onale for External Projec on and Added Value 4.2. Toward Deterritorializa on and Individualiza on? 5. Hypothe cal Conclusion Keywords: Language spread, language dissemination abroad, minority language, Basque, Catalan, Spanish, linguistic value, linguistic market キーワード:言語普及、言語の対外普及、少数言語、バスク語、カタルーニャ語、スペイン語、言語価値、 言語市場 ᮏ✏䛾ⴭసᶒ䛿ⴭ⪅䛜ᡤᣢ䛧䚸 䜽䝸䜶䜲䝔䜱䝤䞉 䝁䝰䞁䝈⾲♧㻠㻚㻜ᅜ㝿䝷䜲䝉䞁䝇䠄㻯㻯㻙㻮㼅㻕ୗ䛻ᥦ౪䛧䜎䛩䚹 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja 萩尾 生 Hagio Sho External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish 「少数言語」 の対外普及 —— バスク語とカタルーニャ語 の 事 例をスペイン語の事例と比較しつつ 44 Abstract This paper explores the value of the external projection of a minority language overseas, taking into account the cases of Basque and Catalan in comparison with Spanish. -

11, Avenue Marceau 75116 Paris Tél. 01 47 20 70 79

LIENS INTERNET Visite nuestra página en Internet / Visitez notre site web : www.paris.cervantes.es Acceda al catálogo en línea y a Mi biblioteca / Accédez à notre catalogue en ligne et à la rubrique Mi biblioteca : http://absysnet.cervantes.es/abnetopac02/abnetcl. exe?SUBC=PARI Participe en nuestro blog / Participez à notre blog : http://biblioteca-paris.blogs.cervantes.es/ HORAIRES Lundi et jeudi de 14h00 à 19h00 Mardi, mercredi et vendredi de 11h00 à 17h00 11, Avenue Marceau [email protected] 75116 Paris http://biblioteca-paris.blogs.cervantes.es/ Tél. 01 47 20 70 79 Fax 01 47 20 27 49 www.paris.cervantes.es Biblioteca Octavio Paz Bibliothèque Octavio Paz La Biblioteca Octavio Paz, situada en el centro de París, alberga una La Bibliothèque Octavio Paz, située en centre-ville, propose une collection colección especializada en España e Hispanoamérica de más de 60.000 spécialisée d’environ 60.000 volumes (livres, périodiques, films et documentos (libros, publicaciones periódicas, películas y documentales documentaires en DVD, audiolivres et livres électroniques, musique sur en DVD, audiolibros, libros electrónicos, música en CD, etc.). Desde el CD, etc.). Le catalogue disponible sur Internet permet la consultation des catálogo en Internet se pueden consultar los fondos, renovar préstamos, fonds ainsi que le renouvellement des prêts, la réservation des articles et hacer reservas y descargar audiolibros y libros electrónicos. le téléchargement de livres audio et électroniques. SERVICIOS SERVICES . Consulta y préstamo (presencial y en línea) . Consultation et prêt (présentiel et en ligne) . Información bibliográfica . Informations bibliographiques . Servicio de documentación . Service de documentation . Préstamo interbibliotecario y obtención de documentos . -

Academic Programme 2014 20

Mario Vargas Llosa with Seamus Heaney at Instituto Cervantes in Dublin TABLE OF CONTENTS Instituto Cervantes 3-4 10 reasons to study at Instituto Cervantes 3 Frequently Asked Questions 4 Why study now? 4 Spanish language courses 5 General language courses 6 Special and online courses 7 Galician, Basque and Catalan 7 Special courses 7 Teacher training programme - formación de profesores de ELE 7 Online Spanish Course (AVE) 7 Registration and fees 8-9 Assessment tests 8 Enrolment 8 Registration office hours 8 Course materials 8 Class size and course cancellations 9 Refunds 9 Attendace 9 DELE Official Certification of Spanish Language Proficiency 10 Autumn examination 10 Spring examination 10 Examination centres in Ireland 10 Dámaso Alonso Library 11 Collections 11 Services 11 Cultural events 12 Academic calendar 2014-2015 13-15 2 Table© Cover of design contents supplied by María Alejandra Gonaldi. Instituto Cervantes Instituto Cervantes, the only official Spanish Government Language Centre, is a public body founded in 1991 to promote Spanish language teaching and knowledge of the cultures of Spanish-speaking countries throughout the world. It is the largest worldwide Spanish teaching organisation, with over 86 branches in five continents. Instituto Cervantes is a non-profit organisation. 10 REASONS TO STUDY AT INSTITUTO CERVANTES 1. Teachers are qualified at University 8. Free assessment tests to ensure that level. They are native Spanish students are in the class that suits speakers and have considerable their needs. experience teaching Spanish as a foreign language. They are periodically 9. Convenient location in the city centre: retrained in the most up-to-date between Trinity College and The teaching methods. -

The Politics of Spanish in the World

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2014 The Politics of Spanish in the World José del Valle CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/84 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Part V Social and Political Contexts for Spanish 6241-0436-PV-032.indd 569 6/4/2014 10:09:40 PM 6241-0436-PV-032.indd 570 6/4/2014 10:09:40 PM 32 The Politics of Spanish in the World Laura Villa and José del Valle Introduction This chapter offers an overview of the spread of Spanish as a global language, focusing on the policies and institutions that have worked toward its promotion in the last two decades. The actions of institutions, as well as those of corporate and cultural agencies involved in this sort of language policy, are to be understood as part of a wider movement of internationalization of financial activities and political influence (Blommaert 2010; Coupland 2003, 2010; Fairclough 2006; Heller 2011b; Maurais and Morris 2003; Wright 2004). Our approach to globalization (Appadurai 2001; Steger 2003) emphasizes agency and the dominance of a few nations and economic groups within the neo-imperialist order of the global village (Del Valle 2011b; Hamel 2005). In line with this framework, our analysis of language and (the discourse of) globalization focuses on the geostrategic dimension of the politics of Spanish in the world (Del Valle 2007b, 2011a; Del Valle and Gabriel-Stheeman 2004; Mar-Molinero and Stewart 2006; Paffey 2012). -

Spanish-British Culture Figures Analyse the Bilateral Cultural Relationship After Brexit

Instituto Cervantes in London 15-19 Devereux Ct, Temple London WC2R 3JJ 020 7201 0750 www.londres.cervantes.es London, February 27th, 2020 Spanish-British culture figures analyse the bilateral cultural relationship after Brexit Outstanding figures of British Hispanic culture have participated in the round table Future: English & Hispanic Culture After Brexit, in which they highlighted the necessity of unifying both countries to face the challenges and seize the opportunities after Brexit. One of the main issues discussed focused on the relevance of Spanish as a relevant language for everyday life and its incredible growth in British schools. The event took place at the Cervantes Theatre under the auspices of the Instituto Cervantes in London and with support from the Spanish Embassy. The round table was introduced by the Ambassador of Spain to the United Kingdom, Carlos Bastarreche as well as the Ambassador of Honduras to the United Kingdom and Dean of the Latin American Ambassador Group, Iván Romero. Subsequently, the director of Instituto Cervantes, Luis García Montero, paid a tribute to British Hispanism, praising the work of great historians and academics such as Sir John Elliott, Sir Paul Preston and the recently deceased, Trevor Dadson. The round table was moderated by the correspondent of El País in the United Kingdom, Rafa de Miguel, and had the following speakers: the director of the English National Ballet (ENB), Tamara Rojo; the Ambassador of Ecuador to the United Kingdom and novelist, Jaime Marchán; former United Kingdom ambassador to Spain, Simon Manley; the director of the Institute for Modern Languages Research (IMLR), Catherine Davies; the president of the Society of Spanish Scientists in the United Kingdom (CERU), Rocio Gaudioso; and the researcher of the Elcano Royal Institute, Ignacio Molina. -

Instituto Cervantes Leeds Spring 2021 Spanish Courses

03 TRAVELLE Learn Spanish at the Instituto Cervantes in Leeds Welcome to the Instituto Cervantes centre Before enrolling, you might find useful to in Leeds, running nonstop since 1993. We read the following information (click to are part of the world's largest and most follow links): important institution dedicated to the teaching of Spanish language and the About the Instituto Cervantes in Leeds promotion of the cultures of the Spanish- Why study Spanish with us speaking countries. Academic curriculum & levels Enrolment & cancellations policy Following health & safety guidelines, in the Technical requirements for the online Spring 2021 term all our courses and classes activities will again be all-online. How to enrol online Enrol and get one year access to our library Students who enrol to one of our courses will get a library card -valid for 1 year- for the Jorge Edwards library of the Instituto Cervantes in Leeds and Manchester. Its catalogue includes textbooks and grammar books, but also the best Spanish and Latin American literature (novels, poetry books and plays), films, music and more. This card will also grant you access to our Online Library, which includes thousands of bibliographic references. There is an Instituto Cervantes free app for Windows, iOs and Google Play. Once enrolled, send an email to [email protected] to apply for your library card. How to enrol to a Spanish course Check your level of Spanish STEP01 If you already know some Spanish but you are a new student at the IC Leeds, get an assessment of your current knowledge in order to be assigned to the most appropiate course for you. -

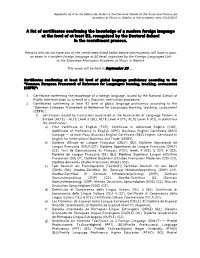

A List of Certificates Confirming the Knowledge of a Modern Foreign Language at the Level of at Least B2, Recognized by the Doctoral School in the Recruitment Process

Appendix no 4 to the Admission Rules to the Doctoral School of the Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music in Gdańsk in the academic year 2020/2021 A list of certificates confirming the knowledge of a modern foreign language at the level of at least B2, recognized by the Doctoral School in the recruitment process. Persons who do not have any of the certificates listed below before matriculation will have to pass an exam in a modern foreign language at B2 level, organized by the Foreign Languages Unit of the Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music in Gdańsk. This exam will be held in September 20..... Certificates confirming at least B2 level of global language proficiency according to the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)": 1. Certificate confirming the knowledge of a foreign language, issued by the National School of Public Administration as a result of a linguistic verification procedure. 2. Certificates confirming at least B2 level of global language proficiency according to the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)": 1) certificates issued by institutions associated in the Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) - ALTE Level 3 (B2), ALTE Level 4 (C1), ALTE Level 5 (C2), in particular the certificates: a) First Certificate in English (FCE), Certificate in Advanced English (CAE), Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE), Business English Certificate (BEC) Vantage — at least Pass, Business English Certificate (BEC) -

Instituto Cervantes De París Cours D'espagnol Adultes Février — Juillet

Instituto Cervantes de París Cours d’espagnol Adultes Février — Juillet 2020 NOTRE OFFRE DE COURS, SELON LE CONTENU INSCRIPTIONS ET MODES DE PAIEMENT Cours généraux d’espagnol, organisés selon En ligne : clicparis.cervantes.es, les niveaux du CECRL, en présentiel et en ligne en sélectionnant le cours avec son code. ( AVE Global ). Cours individuels, d’entreprise Au secrétariat : espèces, chèque ou et packs CPF pour professionnels. carte bancaire. Cours spécialisés : conversation, RÉDUCTIONS perfectionnement, civilisation, préparation Anciens élèves : 10% du DELE et autres. Cours de catalan, galicien Etudiants : 10 %, sur présentation et basque ( contactez-nous ). Cours de français d’une photocopie d’un justificatif pour hispanophones. Demandeurs d’emploi : 10 % sur présentation Cours et stages pour jeunes adultes d’une photocopie d’un justificatif et adolescents ( demandez le dépliant ). Réduction maximale : 20 % OBJECTIFS ET CONTENUS DE NOS COURS GÉNÉRAUX TEST DE PLACEMENT Le curriculum des cours généraux de l’Instituto Test oral et écrit, d’une durée approximative Cervantes de Paris est organisé en cours de 30 minutes. Sans rendez-vous. 25€ de 30 heures académiques ( h.a. ), selon déductibles dès la première inscription. les niveaux du Cadre Européen Commun Pour les horaires, consultez notre page web : de Référence pour les Langues ( CECRL ), paris.cervantes.es/fr/cours/test_niveau.htm . document publié par le Conseil de l’Europe Pas de test les jours sans cours. qui définit des niveaux de maîtrise d’une langue étrangère en fonction de savoir-faire CONDITIONS GÉNÉRALES dans différents domaines de compétence. L’inscription à toute action de formation implique Le document Niveles de referencia para el l’acceptation sans réserve par le participant et español, de l’Instituto Cervantes, définie les son adhésion pleine et entière aux conditions contenus de chaque niveau CECRL pour générales de vente de l’Instituto Cervantes, la langue espagnole. -

Language Requirements

Language Policy NB: This Language Policy applies to applicants of the 20J and 20D MBA Classes. For all other MBA Classes, please use this document as a reference only and be sure to contact the MBA Admissions Office for confirmation. Last revised in October 2018. Please note that this Language Policy document is subject to change regularly and without prior notice. 1 Contents Page 3 INSEAD Language Proficiency Measurement Scale Page 4 Summary of INSEAD Language Requirements Page 5 English Proficiency Certification Page 6 Entry Language Requirement Page 7 Exit Language Requirement Page 8 FL&C contact details Page 9 FL&C Language courses available Page 12 FL&C Language tests available Page 13 Language Tuition Prior to starting the MBA Programme Page 15 List of Official Language Tests recognised by INSEAD Page 22 Frequently Asked Questions 2 INSEAD Language Proficiency Measurement Scale INSEAD uses a four-level scale which measures language competency. This is in line with the Common European Framework of Reference for language levels (CEFR). Below is a table which indicates the proficiency needed to fulfil INSEAD language requirement. To be admitted to the MBA Programme, a candidate must be fluent level in English and have at least a practical level of knowledge of a second language. These two languages are referred to as your “Entry languages”. A candidate must also have at least a basic level of understanding of a third language. This will be referred to as “Exit language”. LEVEL DESCRIPTION INSEAD REQUIREMENTS Ability to communicate spontaneously, very fluently and precisely in more complex situations. -

Fremdsprachenzertifikate in Der Schule

FREMDSPRACHENZERTIFIKATE IN DER SCHULE Handreichung März 2014 Referat 522 Fremdsprachen, Bilingualer Unterricht und Internationale Abschlüsse Redaktion: Henny Rönneper 2 Vorwort Fremdsprachenzertifikate in den Schulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen Sprachen öffnen Türen, diese Botschaft des Europäischen Jahres der Sprachen gilt ganz besonders für junge Menschen. Das Zusammenwachsen Europas und die In- ternationalisierung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft verlangen die Fähigkeit, sich in mehreren Sprachen auszukennen. Fremdsprachenkenntnisse und interkulturelle Er- fahrungen werden in der Ausbildung und im Studium zunehmend vorausgesetzt. Sie bieten die Gewähr dafür, dass Jugendliche die Chancen nutzen können, die ihnen das vereinte Europa für Mobilität, Begegnungen, Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung bietet. Um die fremdsprachliche Bildung in den allgemein- und berufsbildenden Schulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen weiter zu stärken, finden in Nordrhein-Westfalen internationale Zertifikatsprüfungen in vielen Sprachen statt, an denen jährlich mehrere tausend Schülerinnen und Schüler teilnehmen. Sie erwerben internationale Fremdsprachen- zertifikate als Ergänzung zu schulischen Abschlusszeugnissen und zum Europäi- schen Portfolio der Sprachen und erreichen damit eine wichtige Zusatzqualifikation für Berufsausbildungen und Studium im In- und Ausland. Die vorliegende Informationsschrift soll Lernende und Lehrende zu fremdsprachli- chen Zertifikatsprüfungen ermutigen und ihnen angesichts der wachsenden Zahl an- gebotener Zertifikate eine Orientierungshilfe geben.