Why Are There So Few Fish in the Sea?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Global Assessment of Parasite Diversity in Galaxiid Fishes

diversity Article A Global Assessment of Parasite Diversity in Galaxiid Fishes Rachel A. Paterson 1,*, Gustavo P. Viozzi 2, Carlos A. Rauque 2, Verónica R. Flores 2 and Robert Poulin 3 1 The Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, P.O. Box 5685, Torgarden, 7485 Trondheim, Norway 2 Laboratorio de Parasitología, INIBIOMA, CONICET—Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Quintral 1250, San Carlos de Bariloche 8400, Argentina; [email protected] (G.P.V.); [email protected] (C.A.R.); veronicaroxanafl[email protected] (V.R.F.) 3 Department of Zoology, University of Otago, P.O. Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-481-37-867 Abstract: Free-living species often receive greater conservation attention than the parasites they support, with parasite conservation often being hindered by a lack of parasite biodiversity knowl- edge. This study aimed to determine the current state of knowledge regarding parasites of the Southern Hemisphere freshwater fish family Galaxiidae, in order to identify knowledge gaps to focus future research attention. Specifically, we assessed how galaxiid–parasite knowledge differs among geographic regions in relation to research effort (i.e., number of studies or fish individuals examined, extent of tissue examination, taxonomic resolution), in addition to ecological traits known to influ- ence parasite richness. To date, ~50% of galaxiid species have been examined for parasites, though the majority of studies have focused on single parasite taxa rather than assessing the full diversity of macro- and microparasites. The highest number of parasites were observed from Argentinean galaxiids, and studies in all geographic regions were biased towards the highly abundant and most widely distributed galaxiid species, Galaxias maculatus. -

BONY FISHES 602 Bony Fishes

click for previous page BONY FISHES 602 Bony Fishes GENERAL REMARKS by K.E. Carpenter, Old Dominion University, Virginia, USA ony fishes constitute the bulk, by far, of both the diversity and total landings of marine organisms encoun- Btered in fisheries of the Western Central Atlantic.They are found in all macrofaunal marine and estuarine habitats and exhibit a lavish array of adaptations to these environments. This extreme diversity of form and taxa presents an exceptional challenge for identification. There are 30 orders and 269 families of bony fishes presented in this guide, representing all families known from the area. Each order and family presents a unique suite of taxonomic problems and relevant characters. The purpose of this preliminary section on technical terms and guide to orders and families is to serve as an introduction and initial identification guide to this taxonomic diversity. It should also serve as a general reference for those features most commonly used in identification of bony fishes throughout the remaining volumes. However, I cannot begin to introduce the many facets of fish biology relevant to understanding the diversity of fishes in a few pages. For this, the reader is directed to one of the several general texts on fish biology such as the ones by Bond (1996), Moyle and Cech (1996), and Helfman et al.(1997) listed below. A general introduction to the fisheries of bony fishes in this region is given in the introduction to these volumes. Taxonomic details relevant to a specific family are explained under each of the appropriate family sections. The classification of bony fishes continues to transform as our knowledge of their evolutionary relationships improves. -

Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi

Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 (http://www.accessscience.com/) Article by: Boschung, Herbert Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Gardiner, Brian Linnean Society of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, United Kingdom. Publication year: 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400) Content Morphology Euteleostei Bibliography Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi The most recent group of actinopterygians (rayfin fishes), first appearing in the Upper Triassic (Fig. 1). About 26,840 species are contained within the Teleostei, accounting for more than half of all living vertebrates and over 96% of all living fishes. Teleosts comprise 517 families, of which 69 are extinct, leaving 448 extant families; of these, about 43% have no fossil record. See also: Actinopterygii (/content/actinopterygii/009100); Osteichthyes (/content/osteichthyes/478500) Fig. 1 Cladogram showing the relationships of the extant teleosts with the other extant actinopterygians. (J. S. Nelson, Fishes of the World, 4th ed., Wiley, New York, 2006) 1 of 9 10/7/2015 1:07 PM Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 Morphology Much of the evidence for teleost monophyly (evolving from a common ancestral form) and relationships comes from the caudal skeleton and concomitant acquisition of a homocercal tail (upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin are symmetrical). This type of tail primitively results from an ontogenetic fusion of centra (bodies of vertebrae) and the possession of paired bracing bones located bilaterally along the dorsal region of the caudal skeleton, derived ontogenetically from the neural arches (uroneurals) of the ural (tail) centra. -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

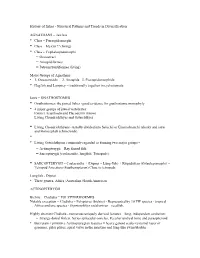

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

Fish-T1K (Transcriptomes of 1,000 Fishes) Project: Large-Scale Transcriptome Data for Fish Evolution Studies Ying Sun1,2*†, Yu Huang2†, Xiaofeng Li2†, Carole C

Sun et al. GigaScience (2016) 5:18 DOI 10.1186/s13742-016-0124-7 COMMENTARY Open Access Fish-T1K (Transcriptomes of 1,000 Fishes) Project: large-scale transcriptome data for fish evolution studies Ying Sun1,2*†, Yu Huang2†, Xiaofeng Li2†, Carole C. Baldwin3, Zhuocheng Zhou4, Zhixiang Yan5, Keith A. Crandall6, Yong Zhang2, Xiaomeng Zhao2, Min Wang2,7, Alex Wong8, Chao Fang2, Xinhui Zhang2, Hai Huang9, Jose V. Lopez10, Kirk Kilfoyle10, Yong Zhang1, Guillermo Ortí6*, Byrappa Venkatesh11* and Qiong Shi2,7,12* Abstract Ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) represent more than 50 % of extant vertebrates and are of great evolutionary, ecologic and economic significance, but they are relatively underrepresented in ‘omics studies. Increased availability of transcriptome data for these species will allow researchers to better understand changes in gene expression, and to carry out functional analyses. An international project known as the “Transcriptomes of 1,000 Fishes” (Fish-T1K) project has been established to generate RNA-seq transcriptome sequences for 1,000 diverse species of ray-finned fishes. The first phase of this project has produced transcriptomes from more than 180 ray-finned fishes, representing 142 species and covering 51 orders and 109 families. Here we provide an overview of the goals of this project and the work done so far. Keywords: Fish-T1K, Fish, Transcriptome, RNA, Database, Biodiversity Background whole genomes of only 38 fish species have been pub- Ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) are the most diverse lished (Additional file 1) and, although the number is and abundant group of extant vertebrates. Thus far, ap- growing (Additional file 2), searching the National Cen- proximately 32,900 fish species are recorded in FishBase ter for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)’s Sequence [1]. -

Euteleostei: Aulopiformes) and the Timing of Deep-Sea Adaptations ⇑ Matthew P

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 57 (2010) 1194–1208 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Estimating divergence times of lizardfishes and their allies (Euteleostei: Aulopiformes) and the timing of deep-sea adaptations ⇑ Matthew P. Davis a, , Christopher Fielitz b a Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, 119 Foster Hall, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA b Department of Biology, Emory & Henry College, Emory, VA 24327, USA article info abstract Article history: The divergence times of lizardfishes (Euteleostei: Aulopiformes) are estimated utilizing a Bayesian Received 18 May 2010 approach in combination with knowledge of the fossil record of teleosts and a taxonomic review of fossil Revised 1 September 2010 aulopiform taxa. These results are integrated with a study of character evolution regarding deep-sea evo- Accepted 7 September 2010 lutionary adaptations in the clade, including simultaneous hermaphroditism and tubular eyes. Diver- Available online 18 September 2010 gence time estimations recover that the stem species of the lizardfishes arose during the Early Cretaceous/Late Jurassic in a marine environment with separate sexes, and laterally directed, round eyes. Keywords: Tubular eyes have arisen independently at different times in three deep-sea pelagic predatory aulopiform Phylogenetics lineages. Simultaneous hermaphroditism evolved a single time in the stem species of the suborder Character evolution Deep-sea Alepisauroidei, the clade of deep-sea aulopiforms during the Early Cretaceous. This result indicates the Euteleostei oldest known evolutionary event of simultaneous hermaphroditism in vertebrates, with the Alepisauroidei Hermaphroditism being the largest vertebrate clade with this reproductive strategy. Divergence times Ó 2010 Elsevier Inc. -

SWFSC Archive

Stomiiformes Chapter 4 Order Stomiiformes Number of suborders (2) Gonostomatoidei; Phosichthyoidei (= Photichthyoidei, Stomioidei). Stomiiform monophyly was demonstrated by Fink and Weitzman (1982); relationships within the order are not settled, e.g., Harold and Weitzman (1996). Number of families 4 (or 5: Harold [1998] suggested that Diplophos, Manducus, and Triplophos do not belong in Gonostomatidae, and Nelson [2006] provi sionally placed them in a separate family, Diplophidae). Number of genera 53 Number of species approx. 391 GENERAL LIFE HISTORY REF Distribution All oceans. Relative abundance Rare to very abundant, depending on taxon. Adult habitat Small to medium size (to ca. 10-40 cm) inhabitants of epi-, meso-, and bathypelagic zones, some are vertical migrators. EARLY LIFE HISTORY Mode of reproduction All species known or assumed to be oviparous with planktonic eggs and larvae. Knowledge of ELH Eggs known for 9 genera, larvae known for 38 genera. ELH Characters: Eggs: spherical, ca. 0.6-3.6 mm in diameter, commonly with double membrane, yolk segmented, with 0-1 oil globule ca. 0.1-0.4 mm in di ameter, perivitelline space narrow to wide. Larvae: slender and elongate initially but some become deep-bodied (primarily some sternoptychids and stomiids); preanal length ranges from approx. 30%BL to > 70% BL, most commonly > about half BL, some taxa with trailing gut that can be > 100% BL; eyes strongly ellipti cal to round, most commonly elliptical, stalked in some species; spines lacking on head and pectoral girdle except in some sternoptychids; myo- meres range from 29-164, most commonly approx. mid-30's to mid- 60's; photophores form during postflexion and/or transformation stage; pigmentation absent to heavy, most commonly light. -

Field Identification Guide to the Living Marine Resources in Kenya

Guide to Orders and Families 81 lateral line scales above scales before dorsal fin outer margin smooth outer margin toothed (predorsal scales) lateral–line 114 scales cycloid ctenoidِّ scales circumpeduncular Schematic examples lateral line of typical scales scales below Common scale counts adipose fin finlets soft rays (segmented, spinyunbranched) rays or spines usually branched) (unsegmented, always Example of a continuous Accessory dorsal and anal dorsal fin of a spiny–rayed fish fins: adipose fin and finlets rounded truncate emarginate lunate side front side front from the dorsal and pointed and separated forked pointed soft rays (branched, spines (solid) segments, 2 halves) anal fins Construction Most common types of fin rays of caudal fins 82 Bony Fishes GUIDE TO ORDERS AND FAMILIES Order ELOPIFORMES – Tarpons and allies Fin spines absent; a single dorsal fin located above middle of body; pelvic fins in abdominal position; lateral line present; 23–25 branchiostegal rays; upper jaw extending past eye; tip of snout not overhanging mouth; colour silvery. ELOPIDAE Page 121 very small scales Ladyfishes To 90 cm. Coastal marine waters and estuaries; pelagic. A single species included in the Guide to Species.underside of head large mouth gular plate MEGALOPIDAE Page 121 last ray long Tarpons large scales To 55 cm. Coastal marine waters and estuaries; pelagic. A single species included in the Guide to Species.underside of head gular plate Order ALBULIFORMES – Bonefishes Fin spines absent; a single dorsal fin located above middle of body; pelvic fins in abdominal position; lateral line present; 6–16 branchiostegal rays; upper jaw not extending as far as front of eye; tip of snout overhanging mouth; colour silvery. -

DEEPFISHMAN Document 5 : Review of Parasites, Pathogens

DEEPFISHMAN Management And Monitoring Of Deep-sea Fisheries And Stocks Project number: 227390 Small or medium scale focused research action Topic: FP7-KBBE-2008-1-4-02 (Deepsea fisheries management) DEEPFISHMAN Document 5 Title: Review of parasites, pathogens and contaminants of deep sea fish with a focus on their role in population health and structure Due date: none Actual submission date: 10 June 2010 Start date of the project: April 1st, 2009 Duration : 36 months Organization Name of lead coordinator: Ifremer Dissemination Level: PU (Public) Date: 10 June 2010 Review of parasites, pathogens and contaminants of deep sea fish with a focus on their role in population health and structure. Matt Longshaw & Stephen Feist Cefas Weymouth Laboratory Barrack Road, The Nothe, Weymouth, Dorset DT4 8UB 1. Introduction This review provides a summary of the parasites, pathogens and contaminant related impacts on deep sea fish normally found at depths greater than about 200m There is a clear focus on worldwide commercial species but has an emphasis on records and reports from the north east Atlantic. In particular, the focus of species following discussion were as follows: deep-water squalid sharks (e.g. Centrophorus squamosus and Centroscymnus coelolepis), black scabbardfish (Aphanopus carbo) (except in ICES area IX – fielded by Portuguese), roundnose grenadier (Coryphaenoides rupestris), orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), blue ling (Molva dypterygia), torsk (Brosme brosme), greater silver smelt (Argentina silus), Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides), deep-sea redfish (Sebastes mentella), alfonsino (Beryx spp.), red blackspot seabream (Pagellus bogaraveo). However, it should be noted that in some cases no disease or contaminant data exists for these species. -

ESA Recovery Plan for the Southern DPS of Eulachon

Agenda Item I.3.a Supplemental NMFS Report 3 (Electronic Only) September 2018 Endangered Species Act Recovery Plan for the Southern Distinct Population Segment of Eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus) Prepared by: National Marine Fisheries Service, West Coast Region U.S. Department of Commerce | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | National Marine Fisheries Service ESA Recovery Plan: Southern DPS Eulachon | 2 This Page Intentionally Left Blank 2017 | National Marine Fisheries Service ESA Recovery Plan: Southern DPS Eulachon | 3 Recovery Plan for Southern Distinct Population Segment of Eulachon Thaleichthys pacificus 2017 | National Marine Fisheries Service ESA Recovery Plan: Southern DPS Eulachon | 4 This Page Intentionally Left Blank 2017 | National Marine Fisheries Service ESA Recovery Plan: Southern DPS E u l a c h o n | 5 Disclaimer Endangered Species Act (ESA) recovery plans delineate such reasonable actions as may be necessary, based upon the best available scientific and commercial data available, for the conservation and survival of listed species. Plans are published by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views, official positions, or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than NMFS. They represent the official position of NMFS only after they have been signed by the Assistant Administrator. ESA recovery plans are guidance and planning documents only; identification of an action to be implemented by any public or private party does not create a legal obligation beyond existing legal requirements. Nothing in this plan should be construed as a commitment or requirement that any Federal agency obligate or pay funds in any one fiscal year in excess of appropriations made by Congress for that fiscal year in contravention of the Anti-Deficiency Act, 31 U.S.C. -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences.