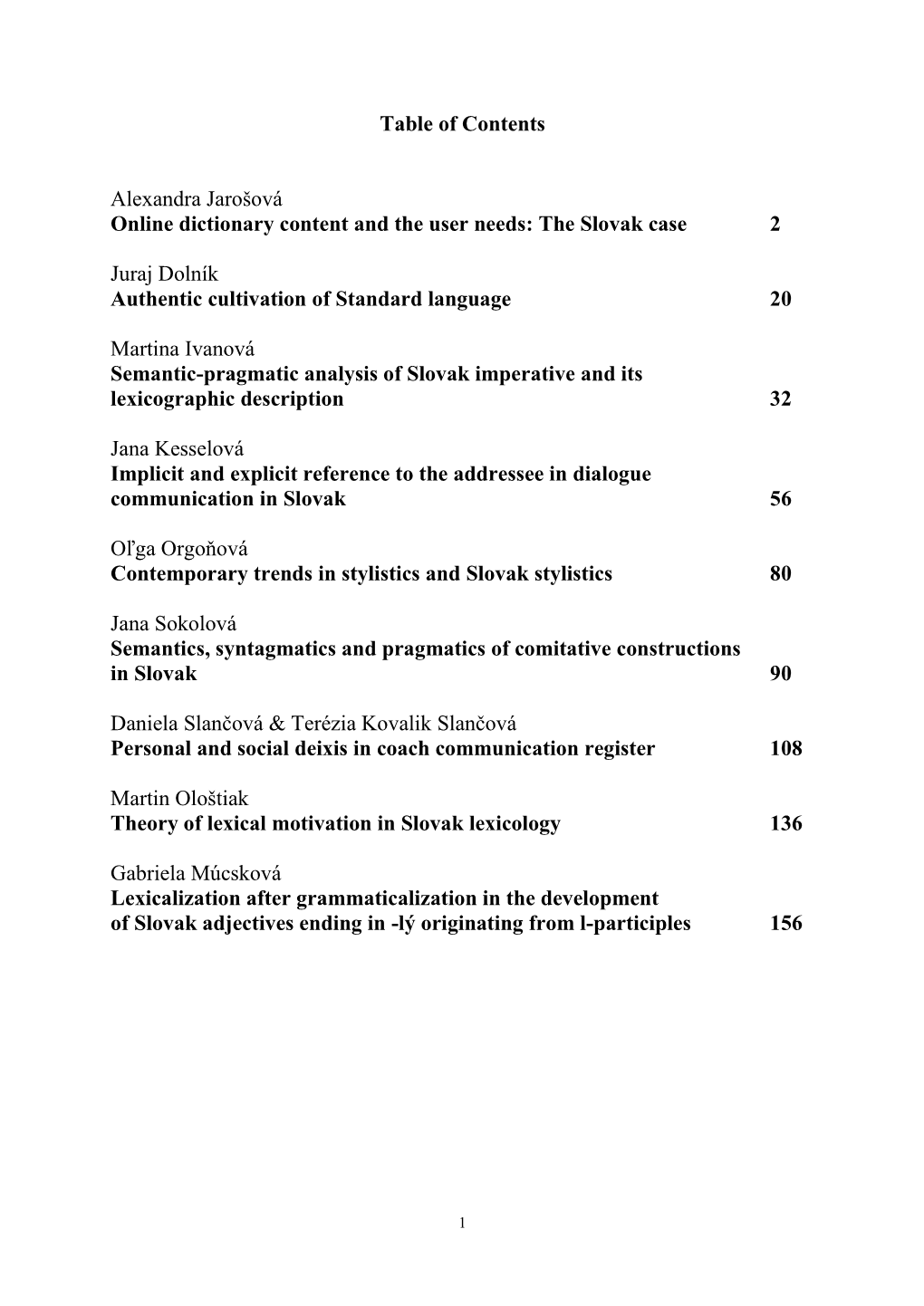

Table of Contents Alexandra Jarošová Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nostratic Grammar: Synthetic Or Analytic?

Nostratic grammar: synthetic or analytic? A. Dolgopolsky Haifa University § 1. The criteria determining the original analytic status of a gram- matical morpheme can be defined as follows. [1] Mobility: in the daughter languages the same morpheme some- times precedes autosemantic words and sometimes follows them (e. g. the pN *mA that forms participles and other deverbal nominals in daugh- ter-languages is found both before and after the verbal root). [2] In some daughter languages the morpheme is still analytic or has phonological evidence for its former analytic status [e. g. the N morpheme *bA (that forms animal names and other nouns of quality bearers) sur- vives in proto-Uralic *-pa; since the N intervocalic *-b- yields pFU *-w-, while the word-initial *b- yields U *p-, the Uralic suffix *pa must go back to a separate word]. [3] A grammatical morpheme of daughter-languages is etymologically identical with a separate word (e. g. the 1st person ending *-mi of the IE verb is identical with the N pronoun *mi that is preserved as a pronoun in daughter-languages). Sometimes other typological features (position in the word) may be taken into account. For instance, if in Semitic and Cushitic (Beja) verbs the feminine marker (*-ī) is used in the 2nd person only and is separated (as a suffix) from the person marker (prefix *t-), it is natural to suppose that it goes back to an address word (Hebrew tiħyī 'you' [f. sg.] will live' < N *t{u} 'thou' + *Хay{u} 'live' + *ʔ{a}yV 'mother'), which is typologically compara- ble with the gender distinction of a yes-word in spoken English: [yesз:] (< yes, sir) vs. -

Comitative Adjuncts: Appositives and Non- Appositives1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Comitative adjuncts: appositives and non- appositives1 Dékány Éva 1. Introduction Expressions involving a comitative adverbial and a plural pronoun as its host DP are ambiguous in Hungarian. In the exclusive reading the comitative is added to the reference of the pronoun, thus in total at least three persons are referred to.2 In the inclusive reading, on the other hand, the referent of the comitative is not added to the referent of the pronoun, but included in it. Under this reading we with John, for instance, refers to two persons: John and me.3 (1) (Mi) Jánossal kisétáltunk a tóhoz.4 we.NOM John-COM PREV-walk-PAST-1PL the lake-ALLAT ‘We walked to the lake with John.’ (exclusive reading) ‘I walked to the lake with John.’ (inclusive reading) In the inclusive reading the most prominent member of the group denoted by the pronoun, whose person feature is the same as that of the pronoun, is termed focal referent. The focal referent in (1) is I. The group denoted by the plural pronoun comprises the focal referent and the referent of the comitative phrase (and nobody else), therefore the comitative is also known as completer phrase (Vassilieva 2005). The aim of this paper is to investigate whether the exclusive and inclusive readings in Hungarian display a strutural difference (cf. Skrabalova 2003 for Czech and Vassilieva 2005 for Russian) or whether non-structural phenomena contribute to their different interpretations (cf. -

Pronouns / Simple Sentences Pronouns

Thamil Paadanool (Draft Version) by Elango Cheran Pronouns / Simple Sentences Pronouns Singluar Plural 1st ehk; we (listener included) I Person ehd; ehq;fs; we (listener not included) 2nd eP you you Person ePq;fs; ePq;fs; you (with respect) mtd; he 3rd mts; she mtu;fs; they Person mtu; he/she (respect) mJ it mit they ("those things") Singular / Plural Singular means that a word refers to only 1 thing. Plural means that a word refers to more than 1 thing. 1st, 2nd, & 3rd Person First person speech means the person speaking is talking about him/herself as an individual ("I...") or in a group ("we..."). In Thamil, ehk; is used when the person who is being spoken to is included in the group. ("Are we there yet?") ehq;fs; is used when the person who is being spoken to is not included. ("We saw a bear! You missed it.") Second person speech means that the person being spoken to is being spoken about. ("Who are you?") ePq;fs; is used for a group of people, as well as for just one person who receives respect. http://www.unc.edu/~echeran/paadanool 1 January 2, 2004 Thamil Paadanool (Draft Version) by Elango Cheran Third person speech means that the speaker is talking with someone about someone else. ("He is good." "They are smart.") mtu; is used when talking about a person who receives respect. mJ refers to anything that is not a person (place, thing, idea). mit is used to refer to more than 1 place, thing, or idea, such as 9 dogs or 5 tables. -

Mixed Languages: YARON MATRAS University of Manchester a Functional±Communicative Approach

Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3 (2), 2000, 79±99 # 2000 Cambridge University Press 79 Mixed languages: YARON MATRAS University of Manchester a functional±communicative approach It has been suggested that the structural composition of mixed languages and the linguistic processes through which they emerge are to some extent predictable, and that they therefore constitute a language ``type'' (e.g. Bakker and Mous, 1994b; Bakker and Muysken, 1995). This view is challenged here. Instead, it is argued that the compartmentalisation of structures observed in mixed languages (i.e. the fact that certain structural categories are derived from one ``parent'' language, others from another) is the result of the cumulative effect of different contact mechanisms. These mechanisms are de®ned in terms of the cognitive and communicative motivations that lead speakers to model certain functions of language on an alternative linguistic system; each mechanism will typically affect particular functional categories. Four relevant processes are identi®ed: lexical re-orientation, selective replication, convergence, and categorial fusion. Different combinations of processes will render different outcomes, hence the diversity of mixed languages as regards their structure, function, and development. terest for a theory of grammar is therefore in de®ning Introduction and explaining qualitative and quantitative differ- Recent collections by Bakker and Mous (1994a) and ences between the effects of contact in mixed lan- by Thomason (1997a) highlight growing interest in guages, as opposed to more conventional linguistic what have been termed ``mixed languages'' or ``bilin- systems. gual mixtures''. Examples of mixed languages that It appears however that few structural properties have received considerable attention in recent litera- are shared by a majority of the languages classi®ed as ture are Michif, the Cree±French mixture spoken by mixed in the literature. -

A Grammar of Wutun

University of Helsinki A Grammar of Wutun PhD Thesis Department of World Cultures Erika Sandman ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV (Main Building), on the 26th of November, 2016 at 10 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 Cover image: A thangka painter in Wutun ISBN 978-951-51-2633-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-2634-4 (PDF) Printed by Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract This study is a grammatical description of Wutun (ISO 639-3 WUH), a distinct local form of Northwest Mandarin spoken by approximately 4000 people in Upper Wutun, Lower Wutun and Jiacangma villages in Tongren County, Huangnan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province, People’s Republic of China. While the Wutun language is genealogically a Sinitic language, it has adapted phonologically and structurally to is current linguistic environment where varieties of Amdo Tibetan are dominant regional languages and lingua francas. The Tibetan influence manifests itself in all domains of Wutun grammatical structure, including phonology, morphology, syntax and lexicon. This has yielded some phonological and grammatical properties that are unusual for a Sintic language and cross-linguistically rare, including the size of a phoneme inventory, multiple aspect marking and egophoricity. The present study is based on first-hand field data collected during three field trips to Qinghai province in June-August 2007, June-August 2010 and June-July 2013. My data includes descriptive and narrative texts, conversations, as well as elicited sentences and grammaticality judgements. The theoretical framework used for language description is based on an informal descriptive theory referred in the literature as Basic Linguistic Theory (BLT) (Dixon 1997, 2010; Dryer 2006). -

Case Theory with the Subject and Object Or Indirect Object of the Hindi Sentences Given Below

4/3/2020 Morphological case • In many Languages, Noun Phrases appear with morphological case in sentences as witnessed Case Theory with the Subject and object or indirect object of the Hindi sentences given below Prof. K. Srikumar • 1. raam ne mohan ko Daraaya Department of Linguistics University of Lucknow • 2. raam ne mohan se baat kii (For MA. Sem II, Paper II) Case in English Morphological case in English • In English, however, NPs realized by proper • But pronouns in English are morphologically names or Full NPs are not marked overtly for distinguished, depending on the position they morphological case. They appear with the hold within the sentence same form irrespective of the position they • He/*Him likes her/*she are in • She/*her spoke about him/*he to everyone John saw Bill • • The asterisked items above signify • Bill gave John some money unacceptability or ungrammaticality. Cont… Case assigner • Further if they are possessive in NPs as in John’s Book they have the forms His,Her, Their etc. said • So pronouns in English have different forms to be Genetive in case. • Their form in the Subject position of sentences • Eventhough proper nouns in English are not is said to be Nominative in case marked for case overtly they do show case effects • And in the Object position of verbs and as pronouns. prepositions, Accusative. • If verbs and prepositions assign accusative case to their complement NPs , Adjectives and nouns in English do not appear to assign case to their complement NPs 1 4/3/2020 Complements of Adj/Noun Of-insertion • *John is [fond/proud Bill/him] • The above examples show that adjectives and • John is [fond/proud of Bill/him] nouns disallow an NP as complement, irrespective of whether they are realized as a full • *John’s [drawings natural landscapes] drew NP or pronoun. -

Case Assignment in Tamil

CASE ASSIGNMENT IN TAMIL Dr. K. Umaraj Lakshmi Pathipakam 374, V.G.R. Puram Alagesan Road, Coimbatore, India Dr. K. Umaraj Case Assignment in Tamil Case Assignment in Tamil Dr. K.Umaraj @ Author First published in : 2007 Page : 92 Size : Demy Copies : 1000 Publishers Lakshmi Pathipakam 374, V.G.R. Puram Alagesan Road Coimbatore Road India Price : 100.00 Printed by THE PARKAR 293, Ahemed Comples, 2 nd Floor Royapettah High Road Chennai – 600 014 Phone : 044 - 65904058 Dr. K. Umaraj Case Assignment in Tamil Dedicated to : MY PARENTS, WIFE AND CHILDERN’S Dr. K. Umaraj Case Assignment in Tamil CONTENT Preface Forward Introduction 9 G B Theory 32 Nominative Case Assignment 52 Objective and Dative Case Assignment 57 Genitive Case Assignment 65 Case and Empty Category pro 69 Conclusion 78 Bibliography 81 Dr. K. Umaraj Case Assignment in Tamil 1. INTRODUCTION 1.11.11.1 Case Case is grammatical category which indicates the syntactic and semantic relationship existing between a noun and a verb or a noun and a noun in a sentence. In Tamil grammatical tradition, the word vēṟṟumai ‘difference’ is used as a technical term to refer to case. According to Tamil grammarians, case differentiates the relationships found between a noun and a verb or a noun and another noun in a sentence and it changes the function of the noun in the syntactic structure or a sentence. The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) descries case as follows: “In inflected languages, one of the varied forms of a substantive adjective or pronoun, which expresses the varied relations in which it may stand to some other word in a sentence (e.g.) a subject or a sub object or a verb, attribute to another ‘noun, object of preposition, etc”. -

A Grammar of Wutun

University of Helsinki A Grammar of Wutun PhD Thesis Department of World Cultures Erika Sandman ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV (Main Building), on the 26th of November, 2016 at 10 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 Cover image: A thangka painter in Wutun ISBN 978-951-51-2633-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-2634-4 (PDF) Printed by Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract This study is a grammatical description of Wutun (ISO 639-3 WUH), a distinct local form of Northwest Mandarin spoken by approximately 4000 people in Upper Wutun, Lower Wutun and Jiacangma villages in Tongren County, Huangnan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province, People’s Republic of China. While the Wutun language is genealogically a Sinitic language, it has adapted phonologically and structurally to is current linguistic environment where varieties of Amdo Tibetan are dominant regional languages and lingua francas. The Tibetan influence manifests itself in all domains of Wutun grammatical structure, including phonology, morphology, syntax and lexicon. This has yielded some phonological and grammatical properties that are unusual for a Sintic language and cross-linguistically rare, including the size of a phoneme inventory, multiple aspect marking and egophoricity. The present study is based on first-hand field data collected during three field trips to Qinghai province in June-August 2007, June-August 2010 and June-July 2013. My data includes descriptive and narrative texts, conversations, as well as elicited sentences and grammaticality judgements. The theoretical framework used for language description is based on an informal descriptive theory referred in the literature as Basic Linguistic Theory (BLT) (Dixon 1997, 2010; Dryer 2006). -

Case Markers in Liangmai

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 14:7 July 2014 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. C. Subburaman, Ph.D. (Economics) Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Case Markers in Liangmai Widinibou Charengna, Ph.D. ==================================================================== Abstract This research paper is intended to explore the nature of case marker in Liangmai language. Case is a grammatical category which expresses the semantic relation between a noun phrase and predicate. Case is a feature that expresses a syntactic and semantic function of the element that carries the particular case value. The case in Liangmai is affected by using suffixes. Liangmai case markers which indicates the suffixes and post positions are added to the nouns and pronouns or to the number affixes to denote case relations. While in English, the major constituents of a sentence can usually be identified by their position in the sentence, Liangmai is a relatively free word-order language. Therefore, the constituents can be moved in the sentence Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 14:7 July 2014 Widinibou Charengna, Ph.D. Case Markers in Liangmai 396 without impacting the core meaning. For example, the following sentence pair conveys the same meaning- Wiraibou saw Akimliu, albeit with different emphases. 1. Wiraibou niu Akimliu tu ngou ye. -

Unimorph Schema)

The Composition and Use of the Universal Morphological Feature Schema (UniMorph Schema) John Sylak-Glassman Center for Language and Speech Processing Johns Hopkins University [email protected] June 2, 2016 c John Sylak-Glassman ** Working Draft, v. 2 ** Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Overview 4 3 Construction Methodology 5 3.1 Guiding Principles . .5 3.2 Constructing the Schema . .6 4 Annotation Formatting Guidelines 7 5 Dimensions of Meaning and Features 8 5.1 Aktionsart . .8 5.2 Animacy . 10 5.3 Argument Marking . 12 5.4 Aspect . 13 5.5 Case . 15 5.5.1 Core Case . 15 5.5.2 Non-Core, Non-Local Case . 16 5.5.3 Local Case . 18 5.6 Comparison . 20 5.7 Definiteness . 21 5.8 Deixis . 22 5.8.1 Distance . 22 5.8.2 Reference Point . 22 5.8.3 Visibility . 23 5.8.4 Verticality . 23 5.8.5 Summary . 24 1 5.9 Evidentiality . 24 5.10 Finiteness . 26 5.11 Gender and Noun Class . 27 5.12 Information Structure . 28 5.13 Interrogativity . 29 5.14 Language-Specific Features . 29 5.15Mood ............................................ 30 5.16 Number . 34 5.17 Part of Speech . 36 5.18 Person . 40 5.19 Polarity . 42 5.20 Politeness . 42 5.20.1 Speaker-Referent Axis . 43 5.20.2 Speaker-Addressee Axis . 44 5.20.3 Speaker-Bystander Axis . 44 5.20.4 Speaker-Setting Axis . 45 5.20.5 Politeness Features . 45 5.21 Possession . 46 5.22 Switch-Reference . 49 5.23 Tense . 53 5.24 Valency . 55 5.25 Voice . -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover next page > title: Lexeme-morpheme Base Morphology : A General Theory of Inflection and Word Formation SUNY Series in Linguistics author: Beard, Robert. publisher: State University of New York Press isbn10 | asin: 0791424715 print isbn13: 9780791424711 ebook isbn13: 9780585045719 language: English subject Grammar, Comparative and general--Morphology. publication date: 1995 lcc: P241.B43 1995eb ddc: 415 subject: Grammar, Comparative and general--Morphology. cover next page > If you like this book, buy it! < previous page page_i next page > Page i Lexeme-Morpheme Base Morphology < previous page page_i next page > If you like this book, buy it! < previous page page_ii next page > Page ii SUNY Series in Linguistics Mark Aronoff, Editor < previous page page_ii next page > If you like this book, buy it! < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii Lexeme-Morpheme Base Morphology A General Theory of Inflection and Word Formation Robert Beard STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS < previous page page_iii next page > If you like this book, buy it! < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv Disclaimer: This book contains characters with diacritics. When the characters can be represented using the ISO 8859-1 character set (http://www.w3.org/TR/images/latin1.gif), netLibrary will represent them as they appear in the original text, and most computers will be able to show the full characters correctly. In order to keep the text searchable and readable on most computers, characters with diacritics that are not part of the ISO 8859-1 list will be represented without their diacritical marks. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 1995 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. -

Malayalam Morphosyntax: Inflectional Features and Their Acquisition

Malayalam Morphosyntax: Inflectional Features and their Acquisition Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Gayathri G Roll No. 134083003 Supervisor: Prof. Vaijayanthi M Sarma Department of Humanities & Social Sciences INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY BOMBAY 2019 For Priya … Abstract Malayalam, which belongs to the SouthDravidian language family, is an agglutinative language with rich inflectional morphology. The aim of the thesis is to analyse the grammar and acqui sition of Malayalam verbal inflections (tense, aspect and mood) and nominal inflections (case, number, and gender). Within the larger discussion of inflectional morphology and its acqui sition, particular attention is paid to two complex morphological processes, a) the past tense formation of verbs and b) case assignment of subjects and objects. In particular, the thesis will show the following: a) that the past tense marker selection is determined by different grammatical principles in underived and derived stems; specifically, phonotactics in the former and the lexical feature of transitivity in the latter; b) that the da tive nominals of a class of predicates (variously labelled experiencer or dative subject or psych predicates) are in fact subjects using an array of empirical tests involving binding, control, ac cusative marking, and predicate alternation; and c) that inflections for number and object case rest on lexical features of the noun (stem) and the allomorphy is governed by these featural requirements. In looking at the developing grammar in the two subjects, the thesis will show that Malayalam inflectional grammar has quite direct consequences for the acquisition of inflec tional morphology.