The Tamil Case System Harold F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

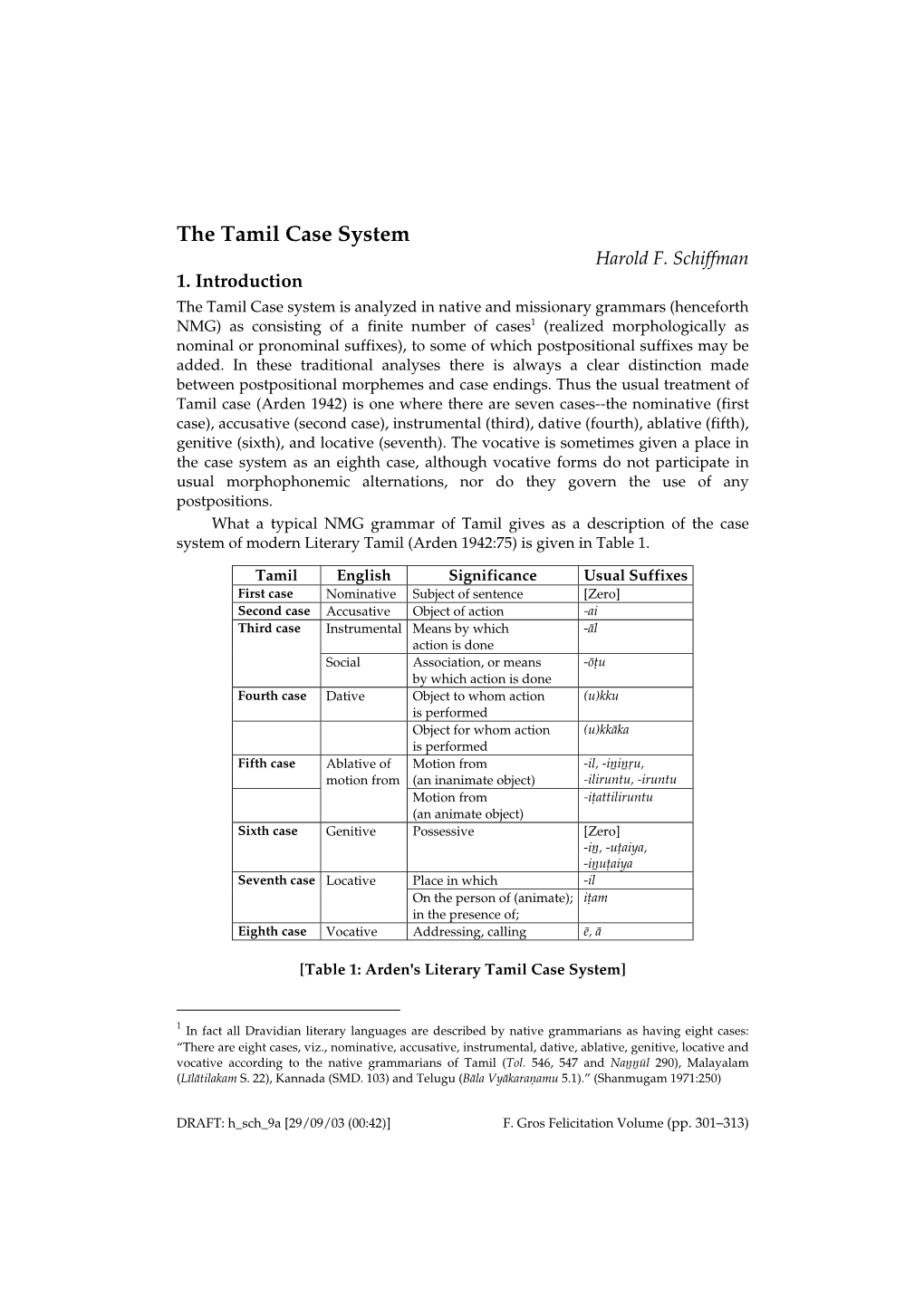

Recommended publications

-

The Strategy of Case-Marking

Case marking strategies Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov1 Radboud University Nijmegen DRAFT January 2006 Abstract Two strategies of case marking in natural languages are discussed. These are defined as two violable constraints whose effects are shown to converge in the case of differential object marking but diverge in the case of differential subject marking. The strength of the case bearing arguments will be shown to be of utmost importance for case marking as well as voice alternations. The strength of arguments can be viewed as a function of their discourse prominence. The analysis of the case marking patterns we find cross-linguistically is couched in a bidirectional OT analysis. 1. Assumptions In this section we wish to put forward our three basic assumptions: (1) In ergative-absolutive systems ergative case is assigned to the first argument x of a two-place relation R(x,y). (2) In nominative-accusative systems accusative case is assigned to the second argument y of a two-place relation R(x,y). (3) Morphologically unmarked case can be the absence of case. The first two assumptions deal with the linking between the first (highest) and second (lowest) argument in a transitive sentence and the type of case marking. For reasons of convenience, we will refer to these arguments quite sloppily as the subject and the object respectively, although we are aware of the fact that the labels subject and object may not be appropriate in all contexts, dependent on how they are actually defined. In many languages, ergative and accusative case are assigned only or mainly in transitive sentences, while in intransitive sentences ergative and accusative case are usually not assigned. -

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

Sinitic Languages of Northwest China: Where Did Their Case Marking Come From?* Dan Xu

Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?* Dan Xu To cite this version: Dan Xu. Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?*. Cao, Djamouri and Peyraube. Languages in contact in Northwestern China, 2015. hal-01386250 HAL Id: hal-01386250 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01386250 Submitted on 31 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?* XU DAN 1. Introduction In the early 1950s, Weinreich (1953) published a monograph on language contact. Although this subject drew the attention of a few scholars, at the time it remained marginal. Over two decades, several scholars including Moravcsik (1978), Thomason and Kaufman (1988), Aikhenvald (2002), Johanson (2002), Heine and Kuteva (2005) and others began to pay more attention to language contact. As Thomason and Kaufman (1988: 23) pointed out, language is a system, or even a system of systems. Perhaps this is why previous studies (Sapir, 1921: 203; Meillet 1921: 87) indicated that grammatical categories are not easily borrowed, since grammar is a system. -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

The Case of Restricted Locatives Ora Matushansky

The case of restricted locatives Ora Matushansky To cite this version: Ora Matushansky. The case of restricted locatives. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung , 2019, 23 (2), 10.18148/sub/2019.v23i2.604. halshs-02431372 HAL Id: halshs-02431372 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02431372 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The case of restricted locatives1 Ora MATUSHANSKY — SFL (CNRS/Université Paris-8)/UiL OTS/Utrecht University Abstract. This paper examines the cross-linguistic phenomenon of locative case restricted to a closed class of items (L-nouns). Starting with Latin, I suggest that the restriction is semantic in nature: L-nouns denote in the spatial domain and hence can be used as locatives without further material. I show how the independently motivated hypothesis that directional PPs consist of two layers, Path and Place, explains the directional uses of L-nouns and the cases that are assigned then, and locate the source of the locative case itself in p0, for which I then provide a clear semantic contribution: a type-shift from the domain of loci to the object domain. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

Oksana's BU Paper

ACQUISITION of GENDER in RUSSIAN * Oksana Tarasenkova University of Connecticut 1 The Background In adult Russian grammar the gender feature of nouns is closely related to their declension class. Their relationship was a controversial question that evoked two opposing views regarding the way gender is represented in adult Russian grammar. The representatives of one view argue for gender to be derived from the noun declension class (Declension-to Gender account, Corbett 1982), while proponents of the opposite account argue for the reversed pattern, where the inflectional morphology can be predicted from the information on the noun gender along with a phonological cue (Gender-to-Declension account, Vinogradov 1960, Thelin 1975, Crockett 1976 among others). My goal is to focus on children’s acquisition of gender in Russian in order to compare these two major divisions of research. They provide different morphological analyses of gender forms in Russian; therefore this debate makes different predictions about the acquisition of gender by children. I tested these opposing predictions using children’s data gathered from an experiment to identify what exactly children rely on when assigning gender to nouns. The experiment results support the Declension-to-Gender view and provide evidence that children are significantly more successful at assigning gender to the novel nouns relying on the nominal declension paradigm rather than on the adjectival agreement. The way gender is represented in adults’ competence grammar might not necessarily be the correct model of children’s acquisition of gender. The child has to learn the gender of a significant number of nouns and extract the declensional paradigms first in order to then be able to learn and apply these redundancy rules for novel nouns. -

GRAMMAR of OLD TAMIL for STUDENTS 1 St Edition Eva Wilden

GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1 st Edition Eva Wilden To cite this version: Eva Wilden. GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1 st Edition. Eva Wilden. Institut français de Pondichéry; École française d’Extrême-Orient, 137, 2018, Collection Indologie. halshs- 01892342v2 HAL Id: halshs-01892342 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01892342v2 Submitted on 24 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1st Edition L’Institut Français de Pondichéry (IFP), UMIFRE 21 CNRS-MAE, est un établissement à autonomie financière sous la double tutelle du Ministère des Affaires Etrangères (MAE) et du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS). Il est partie intégrante du réseau des 27 centres de recherche de ce Ministère. Avec le Centre de Sciences Humaines (CSH) à New Delhi, il forme l’USR 3330 du CNRS « Savoirs et Mondes Indiens ». Il remplit des missions de recherche, d’expertise et de formation en Sciences Humaines et Sociales et en Écologie dans le Sud et le Sud- est asiatiques. Il s’intéresse particulièrement aux savoirs et patrimoines culturels indiens (langue et littérature sanskrites, histoire des religions, études tamoules…), aux dynamiques sociales contemporaines, et aux ecosystèmes naturels de l’Inde du Sud. -

From Latin to Romance: Case Loss and Preservation in Pronominal Systems

FLORE Repository istituzionale dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze From Latin to Romance: case loss and preservation in pronominal systems Questa è la Versione finale referata (Post print/Accepted manuscript) della seguente pubblicazione: Original Citation: From Latin to Romance: case loss and preservation in pronominal systems / Manzini, MARIA RITA; Savoia, LEONARDO MARIA. - In: PROBUS. - ISSN 1613-4079. - STAMPA. - 26, 2(2014), pp. 217-248. Availability: This version is available at: 2158/891750 since: 2016-01-20T16:23:29Z Terms of use: Open Access La pubblicazione è resa disponibile sotto le norme e i termini della licenza di deposito, secondo quanto stabilito dalla Policy per l'accesso aperto dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze (https://www.sba.unifi.it/upload/policy-oa-2016-1.pdf) Publisher copyright claim: (Article begins on next page) 27 September 2021 Probus 2014; 26(2): 217 – 248 M. Rita Manzini* and Leonardo M. Savoia From Latin to Romance: case loss and preservation in pronominal systems Abstract: The evolution from Latin into Romance is marked by the loss of case in nominal declensions. In most Romance varieties, however, pronouns, specifi- cally in the 1st/2nd person singular, keep case differentiations. In some varieties 1st/2nd singular pronouns present a three-way case split, essentially the same re- constructed for proto-Romance (De Dardel and Gaeng 1992, Zamboni 1998). We document and analyze the current situation of Romance in the first part of the article (section 1). In the second part of the article we argue that the Dative Shifted distribution of loro in modern Italian, accounted for by means of the category of weak pronoun in Cardinaletti and Starke (1999), is best construed as a survival of oblique case in the 3rd person system (section 2). -

Nostratic Grammar: Synthetic Or Analytic?

Nostratic grammar: synthetic or analytic? A. Dolgopolsky Haifa University § 1. The criteria determining the original analytic status of a gram- matical morpheme can be defined as follows. [1] Mobility: in the daughter languages the same morpheme some- times precedes autosemantic words and sometimes follows them (e. g. the pN *mA that forms participles and other deverbal nominals in daugh- ter-languages is found both before and after the verbal root). [2] In some daughter languages the morpheme is still analytic or has phonological evidence for its former analytic status [e. g. the N morpheme *bA (that forms animal names and other nouns of quality bearers) sur- vives in proto-Uralic *-pa; since the N intervocalic *-b- yields pFU *-w-, while the word-initial *b- yields U *p-, the Uralic suffix *pa must go back to a separate word]. [3] A grammatical morpheme of daughter-languages is etymologically identical with a separate word (e. g. the 1st person ending *-mi of the IE verb is identical with the N pronoun *mi that is preserved as a pronoun in daughter-languages). Sometimes other typological features (position in the word) may be taken into account. For instance, if in Semitic and Cushitic (Beja) verbs the feminine marker (*-ī) is used in the 2nd person only and is separated (as a suffix) from the person marker (prefix *t-), it is natural to suppose that it goes back to an address word (Hebrew tiħyī 'you' [f. sg.] will live' < N *t{u} 'thou' + *Хay{u} 'live' + *ʔ{a}yV 'mother'), which is typologically compara- ble with the gender distinction of a yes-word in spoken English: [yesз:] (< yes, sir) vs. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP.