Commagenian Funerary Monuments: Ancestry and Identity in the Roman East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Terracotta Figurines of Amisos. 14 I

The Terracotta figurines of Amisos School of Humanities MA in Black Sea Cultural Studies The Terracotta Figurines of Amisos . Name: Eleni Mentesidou Student ID: 221100015 Name of Supervisor: Pr. Styliani Drougou Submission Date: 18 November 2011 0 The Terracotta figurines of Amisos Abstract. The subject of the present dissertation is the terracotta figurines of Amisos’ workshop which is in its most productive period during Mithridates Eupator kingship. The study has been focused on the figurines in relation with the economic, political and religious life of Amisos. Aim of our research was to find out in what extent the city’s economy and culture as the political circumstances, during the period of its activity, affected the production of the amisian terracotta workshop. Before dealing with the main subject has been considered necessary an introduction concerning the location, the geography, the foundation and the history of Amisos in order to be understood the general historical and cultural context that effected the evolvement and the activity of the terracotta workshop. Moreover, the following analysis of Amisos’ economy as the description of the occupations and the products of the amisians demonstrate on the one hand that the production and the exportation of the terracotta figurines were part of Amisos’ economy and on the other hand that the coroplasts of the amisian workshop represent through the selection of their subjects the city’s economical life. The forth chapter deals with the figurines as products of the amisian workshop. However, the lack of scientific treatment coupled with the fact that the figurines are partly preserved and have been diffused all over the world, impedes their study. -

Addenda Et Corrigenda

Christian Settipani CONTINUITE GENTILICE ET CONTINUITE FAMILIALE DANS LES FAMILLES SENATORIALES ROMAINES A L’EPOQUE IMPERIALE MYTHE ET REALITE Addenda I - III (juillet 2000- octobre 2002) P & G Prosopographica et Genealogica 2002 ADDENDA I (juillet 2000 - août 2001) Introduction Un an après la publication de mon livre, il apparaît opportun de donner un premier état des compléments et des corrections que l’on peut y apporter1. Je ne dirais qu’un mot des erreurs de forme, bien trop nombreuses hélas, mais qu’il reste toujours possible d’éliminer. J’ai répertorié ici celles que j’ai relevées au hasard des lectures. En revanche, les corrections de fond s’avèrent un mal rédhibitoire. La mise à jour de nouveaux documents (et on verra que plusieurs inscriptions importantes doivent être ajoutées au dossier), la prise en compte de publications qui m’avaient échappées ou simplement une réflexion différente rendront toujours l’œuvre mouvante et inachevée. Il m’a semblé que pour garder au livre son caractère d’actualité il fallait impérativement tenir à jour des addenda. Une publication traditionnelle aurait pour conséquence que ces addenda seraient eux-mêmes rapidement rendus insuffisants voire obsolètes dans un temps très court, à peine publiés sans doute2. La meilleure solution s’impose donc naturellement : une publication en ligne avec une remise à niveau régulière que l’on trouvera, pour l’instant, sur : http://www.linacre.ox.ac.uk/research/prosop/addrome.doc Il est bien entendu que cet état reste provisoire et ne s’assimile pas encore à une publication formelle et que je reste à l’écoute des suggestions, critiques ou corrections que l’on voudra bien me faire, et que j’essaierai d’en tenir compte du mieux possible3. -

Building Materials and Techniqu63 in the Eastern

BUILDING MATERIALS AND TECHNIQU63 IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN FRUM THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD TO THE FOURTH CENTURY AD by Hazel Dodgeq BA Thesis submitted for the Degree of'PhD at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne Decembert 1984 "When we buildq let us thinjc that we build for ever". John Ruskin (1819 - 1900) To MY FAMILY AND TU THE MEMORY OF J. B. WARD-PERKINS (1912 - 1981) i ABSTRACT This thesis deals primarily with the materials and techniques found in the Eastern Empire up to the 4th century AD, putting them into their proper historical and developmental context. The first chapter examines the development of architecture in general from the very earliest times until the beginnin .g of the Roman Empire, with particular attention to the architecture in Roman Italy. This provides the background for the study of East Roman architecture in detail. Chapter II is a short exposition of the basic engineering principles and terms upon which to base subsequent despriptions. The third chapter is concerned with the main materials in use in the Eastern Mediterranean - mudbrick, timber, stone, mortar and mortar rubble, concrete and fired brick. Each one is discussed with regard to manufacture/quarrying, general physical properties and building uses. Chapter IV deals with marble and granite in a similar way but the main marble types are described individually and distribution maps are provided for each in Appendix I. The marble trade and the use of marble in Late Antiquity are also examined. Chapter V is concerned with the different methods pf wall construction and with the associated materials. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

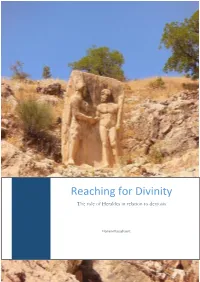

Reaching for Divinity the Role of Herakles in Relation to Dexiosis

Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht University RMA ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL, AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES thesis under the supervision of dr. R. Strootman | prof. L.V. Rutgers Cover Photo: Dexiosis relief of Antiochos I of Kommagene with Herakles at Arsameia on the Nymphaion. Photograph by Stefano Caneva, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license. 1 Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht 2017 2 Acknowledgements The completion of this master thesis would not have been possible were not it for the advice, input and support of several individuals. First of all, I owe a lot of gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Rolf Strootman, whose lectures not only inspired the subject for this thesis, but whose door was always open in case I needed advice or felt the need to discuss complex topics. With his incredible amount of knowledge on the Hellenistic Period provided me with valuable insights, yet always encouraged me to follow my own view on things. Over the course of this study, there were several people along the way who helped immensely by providing information, even if it was not yet published. Firstly, Prof. Dr. Miguel John Versluys, who was kind enough to send his forthcoming book on Nemrud Dagh, an important contribution to the information on Antiochos I of Kommagene. Secondly, Prof. Dr. Panagiotis Iossif who even managed to send several articles in the nick of time to help my thesis. Lastly, the National Numismatic Collection department of the Nederlandse Bank, to whom I own gratitude for sending several scans of Hellenistic coins. -

Mortem Et Gloriam Army Lists Use the Army Lists to Create Your Own Customised Armies Using the Mortem Et Gloriam Army Builder

Army Lists Syria and Asia Minor Contents Asiatic Greek 670 to 129 BCE Lycian 525 to 300 BCE Bithynian 434 to 74 BCE Armenian 330 BCE to 627 CE Asiatic Successor 323 to 280 BCE Cappadocian 300 BCE to 17 CE Attalid Pergamene 282 to 129 BCE Galatian 280 to 62 BCE Early Seleucid 279 to 167 BCE Seleucid 166 to 129 BCE Commagene 163 BCE to 72 CE Late Seleucid 128 to 56 BCE Pontic 110 to 47 BCE Palmyran 258 CE to 273 CE Version 2020.02: 1st January 2020 © Simon Hall Creating an army with the Mortem et Gloriam Army Lists Use the army lists to create your own customised armies using the Mortem et Gloriam Army Builder. There are few general rules to follow: 1. An army must have at least 2 generals and can have no more than 4. 2. You must take at least the minimum of any troops noted and may not go beyond the maximum of any. 3. No army may have more than two generals who are Talented or better. 4. Unless specified otherwise, all elements in a UG must be classified identically. Unless specified otherwise, if an optional characteristic is taken, it must be taken by all the elements in the UG for which that optional characteristic is available. 5. Any UGs can be downgraded by one quality grade and/or by one shooting skill representing less strong, tired or understrength troops. If any bases are downgraded all in the UG must be downgraded. So Average-Experienced skirmishers can always be downgraded to Poor-Unskilled. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Scout Uniform, Scout Sign, Salute and Handshake

In this Topic: Participation Promise and Law Scout Uniform, Scout Salute and Scout Handshake Scouts and Flags Scouting History Discussion with the Scout Leader Introducing Tenderfoot Level The Journey Life in the Troop is a journey. As in any journey one embarks on, there needs to be proper preparation for the adventure ahead. This is important so as to steer clear of obstacles and perils, which, with good foresight, can often be avoided. As Scouts we follow our simple motto: Be Prepared! With this in mind you can start your preparations for the journey ahead… The Tenderfoot This level offers a starting point for a new member in the troop. For those Cubs whose time has come to move up from the pack, the Tenderfoot level is a stepping stone linking the pack with the troop. For those scouts who have joined from outside the group, this will be the beginning of their scouting life. How do I achieve this level? The five sections in this level can be done in any order. If you are a Cub Scout moving up from the pack, you will have already started the Cub Scout link badge. The Tenderfoot level is started at the same time. As you can see some of the requirements are the same for both awards. If you have just joined the scouting movement as part of the troop, this level will provide you with all the basic information to help you learn what scouting is all about. Look at the sheet on the next page so that you are able to keep track of your progress. -

Hand Gestures

L2/16-308 More hand gestures To: UTC From: Peter Edberg, Emoji Subcommittee Date: 2016-10-31 Proposed characters Tier 1: Two often-requested signs (ILY, Shaka, ILY), and three to complete the finger-counting sets for 1-3 (North American and European system). None of these are known to have offensive connotations. HAND SIGN SHAKA ● Shaka sign ● ASL sign for letter ‘Y’ ● Can signify “Aloha spirit”, surfing, “hang loose” ● On Emojipedia top requests list, but requests have dropped off ● 90°-rotated version of CALL ME HAND, but EmojiXpress has received requests for SHAKA specifically, noting that CALL ME HAND does not fulfill need HAND SIGN ILY ● ASL sign for “I love you” (combines signs for I, L, Y), has moved into mainstream use ● On Emojipedia top requests list HAND WITH THUMB AND INDEX FINGER EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 2, European style ● ASL sign for letter ‘L’ ● Sign for “loser” ● In Montenegro, sign for the Liberal party ● In Philippines, sign used by supporters of Corazon Aquino ● See Wikipedia entry HAND WITH THUMB AND FIRST TWO FINGERS EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 3, European style ● UAE: Win, victory, love = work ethic, success, love of nation (see separate proposal L2/16-071, which is the source of the information below about this gesture, and also the source of the images at left) ● Representation for Ctrl-Alt-Del on Windows systems ● Serbian “три прста” (tri prsta), symbol of Serbian identity ● Germanic “Schwurhand”, sign for swearing an oath ● Indication in sports of successful 3-point shot (basketball), 3 successive goals (soccer), etc. HAND WITH FIRST THREE FINGERS EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 3, North American style ● ASL sign for letter ‘W’ ● Scout sign (Boy/Girl Scouts) is similar, has fingers together Tier 2: Complete the finger-counting sets for 4-5, plus some less-requested hand signs. -

La Storia Della Mentalità Delle Élites Dell'impero Romano Come Viaggio

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PISA Scuola di Dottorato in Storia, Orientalistica e Storia delle Arti XXV Ciclo Tesi di Dottorato in Storia Antica LA STORIA DELLA MENTALITÀ DELLE ÉLITES DELL’IMPERO ROMANO COME VIAGGIO PER ISOLE LESSICALI Relatore Candidata Prof. Giovanni Salmeri Francesca Zaccaro Sommario Introduzione. La storia della mentalità delle 1 élites dell’impero romano come viaggio per isole lessicali I. L’isola dell’affettività: eunoia tra spazio 16 civico e spazio domestico II. L’isola della praotēs: l’elogio della mitezza 59 III. L’isola dell’epieikeia: il corredo etico 84 dell’impero IV. L’isola del kosmos: gli ornamenti 121 dell’impero V. L’arcipelago latino tra isole minori e atolli 142 VI. Si può parlare di mentalità delle élites 174 femminili sotto l’impero romano? VII. La paideia nella pratica: i maîtres à penser 211 della mentalità Bibliografia 233 Index 265 Introduzione La storia della mentalità delle élites dell’impero romano come viaggio per isole lessicali Questa ricerca si pone l’obiettivo di ricostruire la mentalità delle élites dirigenti ed intellettuali dell’impero romano nei primi due secoli dopo Cristo. Il principale strumento con cui ho portato avanti l’indagine è stata un’analisi di tipo lessicale con cui ho individuato, sulla base dei documenti letterari ed epigrafici, dei nuclei ‒ delle isole come vedremo meglio in seguito ‒ che contengono i codici comportamentali sia pubblici sia privati, sia politici sia familiari, delle élites. Queste isole dell’arcipelago lessicale1 sono presenti dei termini e delle espressioni che prima del periodo preso in considerazione avevano un significato diverso, lontano dall’aura di continenza e temperanza che agita le correnti dell’arcipelago lessicale. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it.