Dochas Is Duchas, Hope and Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The$Irish$Language$And$Everyday$Life$ In#Derry!

The$Irish$language$and$everyday$life$ in#Derry! ! ! ! Rosa!Siobhan!O’Neill! ! A!thesis!submitted!in!partial!fulfilment!of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of! Doctor!of!Philosophy! The!University!of!Sheffield! Faculty!of!Social!Science! Department!of!Sociological!Studies! May!2019! ! ! i" " Abstract! This!thesis!explores!the!use!of!the!Irish!language!in!everyday!life!in!Derry!city.!I!argue!that! representations!of!the!Irish!language!in!media,!politics!and!academic!research!have! tended!to!overKidentify!it!with!social!division!and!antagonistic!cultures!or!identities,!and! have!drawn!too!heavily!on!political!rhetoric!and!a!priori!assumptions!about!language,! culture!and!groups!in!Northern!Ireland.!I!suggest!that!if!we!instead!look!at!the!mundane! and!the!everyday!moments!of!individual!lives,!and!listen!to!the!voices!of!those!who!are! rarely!heard!in!political!or!media!debate,!a!different!story!of!the!Irish!language!emerges.! Drawing!on!eighteen!months!of!ethnographic!research,!together!with!document!analysis! and!investigation!of!historical!statistics!and!other!secondary!data!sources,!I!argue!that! learning,!speaking,!using,!experiencing!and!relating!to!the!Irish!language!is!both!emotional! and!habitual.!It!is!intertwined!with!understandings!of!family,!memory,!history!and! community!that!cannot!be!reduced!to!simple!narratives!of!political!difference!and! constitutional!aspirations,!or!of!identity!as!emerging!from!conflict.!The!Irish!language!is! bound!up!in!everyday!experiences!of!fun,!interest,!achievement,!and!the!quotidian!ebbs! and!flows!of!daily!life,!of!getting!the!kids!to!school,!going!to!work,!having!a!social!life!and! -

Irish Parents and Gaelic- Medium Education in Scotland

Irish parents and Gaelic- medium education in Scotland A Report for Soillse 2015 Wilson McLeod Bernadette O’Rourke Table of content 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 2 2. Setting the scene ................................................................................................................... 3 3. Previous research .................................................................................................................. 4 4. Profile of Irish parent group ................................................................................................... 5 5. Relationship to Irish: socialisation, acquisition and use ......................................................... 6 6. Moving to Scotland: when and why? ................................................................................... 12 7. GME: awareness, motivations and experiences .................................................................. 14 8. The Gaelic language learning experience and use of Gaelic .............................................. 27 9. Sociolinguistic perceptions of Gaelic ................................................................................... 32 10. Current connections with Ireland ...................................................................................... 35 11. Conclusions ...................................................................................................................... 38 Acknowledgements -

A Revitalization Study of the Irish Language

TAKING THE IRISH PULSE: A REVITALIZATION STUDY OF THE IRISH LANGUAGE Donna Cheryl Roloff Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2015 APPROVED: John Robert Ross, Committee Chair Kalaivahni Muthiah, Committee Member Willem de Reuse, Committee Member Patricia Cukor-Avila, Director of the Linguistics Program Greg Jones, Interim Dean of College of Information Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Roloff, Donna Cheryl. Taking the Irish Pulse: A Revitalization Study of the Irish Language. Master of Arts (Linguistics), December 2015, 60 pp., 22 tables, 3 figures, references, 120 titles. This thesis argues that Irish can and should be revitalized. Conducted as an observational case study, this thesis focuses on interviews with 72 participants during the summer of 2013. All participants live in the Republic of Ireland or Northern Ireland. This thesis investigates what has caused the Irish language to lose power and prestige over the centuries, and which Irish language revitalization efforts have been successful. Findings show that although, all-Irish schools have had a substantial growth rate since 1972, when the schools were founded, the majority of Irish students still get their education through English- medium schools. This study concludes that Irish will survive and grow in the numbers of fluent Irish speakers; however, the government will need to further support the growth of the all-Irish schools. In conclusion, the Irish communities must take control of the promotion of the Irish language, and intergenerational transmission must take place between parents and their children. Copyright 2015 by Donna Cheryl Roloff ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND THE DETERIORATION 13 OF THE IRISH LANGUAGE CHAPTER 3 IRISH SHOULD BE REVIVED 17 CHAPTER 4 IRISH CAN BE REVIVED 28 CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSION 44 REFERENCES 53 iii LIST OF TABLES Page 1. -

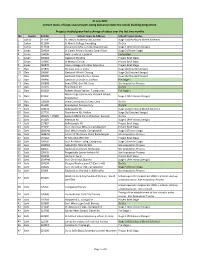

31 July 2021 Current Status of Large-Scale Projects Being Delivered Under the School Building Programme

31 July 2021 Current status of large-scale projects being delivered under the school building programme. Projects shaded green had a change of status over the last two months No. County Roll No School Name & Address School Project Status 1 Carlow 61120E St. Mary's Academy CBS, Carlow Stage 2a (Developed Sketch Scheme) 2 Carlow 61130H St Mary's College, Knockbeg On Site 3 Carlow 61150N Presentation/De La Salle, Bagnelstown Stage 1 (Preliminary Design) 4 Cavan 08490N St Clare's Primary School, Cavan Town Stage 3 (Tender Stage) 5 Cavan 19439B Holy Family SS, Cootehill Completed 6 Cavan 20026G Gaelscoil Bhreifne Project Brief Stage 7 Cavan 70360C St Mogues College Project Brief Stage 8 Cavan 76087R Cavan College of Further Education Project Brief Stage 9 Clare 17583V SN Cnoc an Ein, Ennis Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 10 Clare 19838P Gaelscoil Mhichil Chiosog Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 11 Clare 19849U Gaelscoil Donncha Rua, Sionna Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 12 Clare 19999Q Gaelscoil Ui Choimin, Cill Rois Pre Stage 1 13 Clare 20086B Ennis ETNS, Gort Rd, Ennis Site Acquisition Process 14 Clare 20245S Ennistymon NS On Site 15 Clare 20312H Raheen Wood Steiner, Tuamgraney Pre Stage 1 Mol an Óige Community National School, 16 Clare 20313J Stage 1 (Preliminary Design) Ennistymon 17 Clare 70830N Ennis Community College, Ennis On Site 18 Clare 91518F Ennistymon Post primary On Site 19 Cork 00467B Ballinspittle NS Stage 2a (Developed Sketch Scheme) 20 Cork 13779S Dromahane NS, Mallow Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 21 Cork 14052V / 17087J Kanturk BNS & SN -

Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Pages 1–9, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, July 27–31, 2011

EMNLP 2011 DIALECTS2011 Proceedings of the First Workshop on Algorithms and Resources for Modelling of Dialects and Language Varieties July 31, 2011 Edinburgh, Scotland, UK c 2011 The Association for Computational Linguistics Order copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ISBN 978-1-937284-17-6 / 1-937284-17-4 ii Introduction Language varieties (and specifically dialects) are a primary means of expressing a person’s social affiliation and identity. Hence, computer systems that can adapt to the user by displaying a familiar socio-cultural identity are expected to raise the acceptance within certain contexts and target groups dramatically. Although the currently prevailing statistical paradigm has made possible major achievements in many areas of natural language processing, the applicability of the available methods is generally limited to major languages / standard varieties, to the exclusion of dialects or varieties that substantially differ from the standard. While there are considerable initiatives dealing with the development of language resources for minor languages, and also reliable methods to handle accents of a given language, i.e., for applications like speech synthesis or recognition, the situation for dialects still calls for novel approaches, methods and techniques to overcome or circumvent the problem of data scarcity, but also to enhance and strengthen the standing that language varieties and dialects have in natural language processing technologies, as well as in interaction technologies that build upon the former. What made us think that a such a workshop would be a fruitful enterprise was our conviction that only joint efforts of researchers with expertise in various disciplines can bring about progress in this field. -

Shopkindly That Has Been Missed, Notify the Business and Give Them the Opportunity to Remedy It Rather Than Posting on Social Media

SPECIAL FEATURE: Life Less Ordinary Living in a pandemic People from around West Cork share their experiences. www.westcorkpeople.ie & www.westcorkfridayad.ie October 2 – October 30, 2020, Vol XVI, Edition 218 FREE Old Town Hall, McCurtain Hill, Clonakilty, Co. Cork. E: [email protected] P: 023 8835698 SILENCE IS GOLDEN. NEW PEUGEOT e-208 FULL ELECTRIC From Direct Provision to Cork Persons of the Month: Izzeddeen and wife Eman Alkarajeh left direct provision in Cork and, together with their four children, overcame all odds to build a new life and successful Palestinian food business in Cork. They are pictured at their Cork Persons of Month award presentation with (l-r) Manus O’Callaghan and award organiser, George Duggan, Cork Crystal. Picture: Tony O’Connell Photography. *Offer valid until the end of August. CLARKE BROS LTD Main Peugeot Dealer, Clonakilty Road, Bandon, Co. Cork. Clune calls on Government to “mind our air routes” Tel: 023-8841923CLARKE BROS Web: www.clarkebrosgroup.ie ction is needed on the Avia- Irish Aviation Sector to recover from but also to onward flights through the to Ireland’s economy and its economic (BANDON) LTD tion Recovery Taskforce Re- the impact of Covid 19. One of the international airline hubs as well as recovery. Main Peugeot Dealers port to ensure we have strong recommendations of the Aviation excellent train access across Europe. The report said that a stimulus Clonakilty Road, Aregional airports post-Covid. This Recovery Taskforce Report was to MEP Clune added: “This is a very package should be put in place con- is according to Ireland South MEP provide a subvention per passenger difficult time for our airlines and air- currently for each of Cork, Shannon, Bandon Deirdre Clune who said it should be at Cork, Shannon and other Regional ports but we must ensure that they get Ireland West, Kerry and Donegal Co. -

The Irish Language and the Irish Legal System:- 1922 to Present

The Irish Language and The Irish Legal System:- 1922 to Present By Seán Ó Conaill, BCL, LLM Submitted for the Award of PhD at the School of Welsh at Cardiff University, 2013 Head of School: Professor Sioned Davies Supervisor: Professor Diarmait Mac Giolla Chríost Professor Colin Williams 1 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… 2 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… -

I IRISH MEDIUM EDUCATION

IRISH MEDIUM EDUCATION: COGNITIVE SKILLS, LINGUISTIC SKILLS, AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS IRISH. IVAN ANTHONY KENNEDY PhD COLLEGE OF EDUCATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING, BANGOR UNIVERSITY 2012 i In memory of Tony. No one speaks English, and everything's broken, and my Stacys are soaking wet. ~Tom Waits, Tom Traubert's Blues ii There’s a ghost of another language shadow-dancing under my words. A phantom tongue that unravels like liquor, inspires like song. ~Sharanya Manivannann, First Language Education is simply the soul of a society as it passes from one generation to another. ~G.K. Chesterton iii Acknowledgements First, and foremost, I thank my supervisor, Dr. Enlli Thomas, for all the guidance over the years. Thank you Enlli for all your constructive and friendly support and for helping me to find and embark upon the right paths throughout this project. Your immense diligence, encouragement, and support went beyond measure and I will be forever grateful for the opportunities that you gave me. From start to finish, working with you on this project was an absolute pleasure. I also thank An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta & Gaelscolaíochta for their financial support in funding this project which made its undertaking possible. Thank you Pól Ó Cainin and Muireann Ní Mhóráin for your help. I thank Siân Wyn Lloyd-Williams for all the moral and academic support throughout the project. Your input is truly valued, helped to keep me grounded, and made the project more fun and less stressful than it might otherwise have been. Additionally, I thank Dave Lane for his expertise in creating the Flanker tasks and the Sustained Attention to Response Task computer programs, Gwyn Lewis and Jean Ware for academic assistance and feedback, Beth Lye and Mirain Rhys for scoring children’s written tests, and Raymond Byrne and Ross Byrne for helping to create and pilot the Irish vocabulary tests. -

A Social Network Analysis of Irish Language Use in Social Media

A SOCIAL NETWORK ANALYSIS OF IRISH LANGUAGE USE IN SOCIAL MEDIA JOHN CAULFIELD School of Welsh Cardiff University 2013 This thesis is submitted to the School of Welsh, Cardiff University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………….. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………….. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………….. STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………….. STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date …………………. 2 ABSTRACT A Social Network Analysis of Irish Language Use in Social Media Statistics show that the world wide web is dominated by a few widely spoken languages. However, in quieter corners of the web, clusters of minority language speakers can be found interacting and sharing content. -

Region Focus: Ireland Core Focus

Language | Technology | Business April/May 2013 Region Focus: Ireland The changing Irish language demographic Software localization into the Irish language Localization industry in Ireland Internationalization of small Irish businesses Core Focus: Translation Using macros to improve translation efficiency Translation trends: Interviews from the ATA conference Online resources as a tool for the technical translator 01CoverIrishTombLandscape#135.indd 1 3/29/13 8:49 AM Beautifully Finished Transform your translation process and double your throughput. Combine the power of secure and customizable SDL machine translation with the expertise of your translators. Are you ready to join the post-editing revolution? SDL, the world leaders in Translation Technology brings you- 3 easy steps to transform your localization process: Choose SDL BeGlobal, SDL’s Connect to the market leading Add the unique skills of your secure and customizable translation software, SDL translators to create a beautifully 1 machine translation tool 2 Trados Studio 3 finished job… Double your productivity with SDL BeGlobal. What’s your strategy for Machine Translation? Talk to us about your plans. Contact us on +44 (0)1628 417227 sdl.com | translationzone.com/beglobal 2-3 MLC.com #135.indd 2 3/29/13 8:50 AM on the web at www.multilingual.com MultiLingual What does that word mean? #135 Volume 24 Issue 3 Ever run across April/May 2013 a word in MultiLingual and you aren’t sure of its Editor-in-Chief, Publisher: Donna Parrish meaning? Perhaps it is a Managing Editor: Katie Botkin word that has been around Editorial Assistant: Jim Healey for a long time, but now in Proofreaders: Bonnie Hagan, Bernie Nova News: Kendra Gray our technical jargon it has Production: Darlene Dibble, Doug Jones taken on a new meaning. -

Colmcille 2019/20

Colmcille 2019/20 Bha Bòrd na Gàidhlig toilichte taic-airgid a thoirt dha na 17 pròiseactan seo tro sgeama Cholmcille 2019/20: Bòrd na Gàidhlig was delighted to award funding to the following 17 projects through the 2019/20 Colmcille fund: Còd / Code Buidheann / Organisation Pròiseact / Project Tabhartas / Award 1920/201 1920/208 5 dhaoine fa leth Cùrsaichean Gaeilge £1,334 1920/211 5 individuals Gaeilge Courses 1920/221 A’ toirt taic do chòignear airson cùrsaichean Gaeilge a dhèanamh ann an Supporting five people to take part in Irish courses in Ireland Èirinn 1920/202 Irish Pages Crossways 2019 £4,000 A’ cur air dòigh fèis litreachais ann an Glaschu a tha a’ toirt còmhla Organising a literary festival in Glasgow bringing together writers and sgrìobhadairean agus luchd-ealain bho Èirinn agus Alba artists from Ireland and Scotland Turas dhan Phloc 1920/203 Gairmscoil Chu Ulaidh £5,400 Trip to Plockton A’ cur ri na ceanglaichean eadar Gairmscoil Chu Ulaidh agus Àrd-sgoil a’ Strengthening the ties between Gairmscoil Chu Ulaidh and Plockton High Phluic tro thuras fad seachdain School through a week-long trip Crìosdachd Thràth Uibhist 1920/204 Ceòlas Uibhist £5,000 Early Christianity in Uist Pròiseact a tha a’ gleidheadh agus a’ clàradh beul-aithris bho mhuinntir A project preserving and recording folklore from the people of Uist on Uibhist co-cheangailte ris na ciad naoimh agus sgeulachdan a bhuineas the first saints and the stories associated with them riutha 1920/205 Iomain Cholmchille Iomain Cholmchille XII £10,000 Tachartas le geamaichean -

A Letter from Ireland: Volume 2

A Letter from Ireland: Volume 2 Mike Collins lives in County Cork, Ireland. He travels around the island of Ireland with his wife, Carina, taking pictures and listening to stories about families, names and places. He and Carina share these pictures and stories at: www.YourIrishHeritage.com He also writes a weekly Letter from Ireland, which is sent out to people of Irish ancestry all over the world. This volume is the second collection of those letters. A Letter from Ireland: Volume 2 Irish Surnames, Counties, Culture and Travel Mike Collins Your Irish Heritage. First published 2014 by Your Irish Heritage Email: [email protected] Website: www.youririshheritage.com © Mike Collins 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. All quotations have been reproduced with original spelling and punctuation. All errors are the author’s own. CREDITS All photographs and illustrative materials are the author’s own. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the many individuals who granted A Letter from Ireland permission to reprint the cited material. ISBN: DESIGN Cover design by Ian Armstrong, Onevision Media Your Irish Heritage, Old Abbey, Cork, Ireland PRAISE FOR ‘A LETTER FROM IRELAND’ It's a great book for those, like myself, who have read a great deal about the history in which my ancestors live but still scratch their heads feeling like there's something missing. Mike fills in many of those gaps in interesting and thought provoking ways, making you crave more.