A Revitalization Study of the Irish Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The$Irish$Language$And$Everyday$Life$ In#Derry!

The$Irish$language$and$everyday$life$ in#Derry! ! ! ! Rosa!Siobhan!O’Neill! ! A!thesis!submitted!in!partial!fulfilment!of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of! Doctor!of!Philosophy! The!University!of!Sheffield! Faculty!of!Social!Science! Department!of!Sociological!Studies! May!2019! ! ! i" " Abstract! This!thesis!explores!the!use!of!the!Irish!language!in!everyday!life!in!Derry!city.!I!argue!that! representations!of!the!Irish!language!in!media,!politics!and!academic!research!have! tended!to!overKidentify!it!with!social!division!and!antagonistic!cultures!or!identities,!and! have!drawn!too!heavily!on!political!rhetoric!and!a!priori!assumptions!about!language,! culture!and!groups!in!Northern!Ireland.!I!suggest!that!if!we!instead!look!at!the!mundane! and!the!everyday!moments!of!individual!lives,!and!listen!to!the!voices!of!those!who!are! rarely!heard!in!political!or!media!debate,!a!different!story!of!the!Irish!language!emerges.! Drawing!on!eighteen!months!of!ethnographic!research,!together!with!document!analysis! and!investigation!of!historical!statistics!and!other!secondary!data!sources,!I!argue!that! learning,!speaking,!using,!experiencing!and!relating!to!the!Irish!language!is!both!emotional! and!habitual.!It!is!intertwined!with!understandings!of!family,!memory,!history!and! community!that!cannot!be!reduced!to!simple!narratives!of!political!difference!and! constitutional!aspirations,!or!of!identity!as!emerging!from!conflict.!The!Irish!language!is! bound!up!in!everyday!experiences!of!fun,!interest,!achievement,!and!the!quotidian!ebbs! and!flows!of!daily!life,!of!getting!the!kids!to!school,!going!to!work,!having!a!social!life!and! -

NOYEK (1873-1932) and ELIZA (BESSIE GERTRUDE) PRICE (1880-1961)

Presented by the KehilaLinks site for Užventis, Lithuania, Hosted by JewishGen My paternal grandparents DANIEL ZVI (HARRIS DANIEL) NOYEK (1873-1932) and ELIZA (BESSIE GERTRUDE) PRICE (1880-1961) ...by Davida Noyek Handler DANIEL ZVI (HARRIS DANIEL) NOYEK - 2nd child of Aaron Hillel NOIECK) – youngest of eight children - was born September 3, 1873, in Užventis, Lithuania. The severity and frequency of pogroms against the Jews of the Russian Empire had intensified following the promulgation of the May Laws of 1881, and it had become increasingly dangerous for the Noyek family to remain in Lithuania, even though they had lived there since the 1700s. Most of our Jewish ancestors left their shtetlach (small villages) within the “Pale of Settlement” in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1897, about 300 Jews still lived in Uzventis. Many had already left for the United States, South Africa, England, and Ireland. In the autumn of 1894, about a year after the birth of their youngest sibling, Harris Daniel and his older brother Abraham left Uzventis, eventually ending up in Dublin, Ireland. Their journey took more than three years! It had encompassed over 1500 miles, much of it on foot, through Poland, Germany, Holland, and England. Neither one at that time spoke any English - only Yiddish and Russian. They arrived in Dublin in February 1897, having completed a large part of their travels walking, by train, and in steerage on Lithuanian grain ships. An endearing story handed down (which may never be verified) tells of one family member (possibly Abraham) who financed their exit by creeping up to the Russian Soldiers camps at night. -

Irish Parents and Gaelic- Medium Education in Scotland

Irish parents and Gaelic- medium education in Scotland A Report for Soillse 2015 Wilson McLeod Bernadette O’Rourke Table of content 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 2 2. Setting the scene ................................................................................................................... 3 3. Previous research .................................................................................................................. 4 4. Profile of Irish parent group ................................................................................................... 5 5. Relationship to Irish: socialisation, acquisition and use ......................................................... 6 6. Moving to Scotland: when and why? ................................................................................... 12 7. GME: awareness, motivations and experiences .................................................................. 14 8. The Gaelic language learning experience and use of Gaelic .............................................. 27 9. Sociolinguistic perceptions of Gaelic ................................................................................... 32 10. Current connections with Ireland ...................................................................................... 35 11. Conclusions ...................................................................................................................... 38 Acknowledgements -

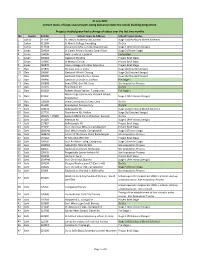

31 July 2021 Current Status of Large-Scale Projects Being Delivered Under the School Building Programme

31 July 2021 Current status of large-scale projects being delivered under the school building programme. Projects shaded green had a change of status over the last two months No. County Roll No School Name & Address School Project Status 1 Carlow 61120E St. Mary's Academy CBS, Carlow Stage 2a (Developed Sketch Scheme) 2 Carlow 61130H St Mary's College, Knockbeg On Site 3 Carlow 61150N Presentation/De La Salle, Bagnelstown Stage 1 (Preliminary Design) 4 Cavan 08490N St Clare's Primary School, Cavan Town Stage 3 (Tender Stage) 5 Cavan 19439B Holy Family SS, Cootehill Completed 6 Cavan 20026G Gaelscoil Bhreifne Project Brief Stage 7 Cavan 70360C St Mogues College Project Brief Stage 8 Cavan 76087R Cavan College of Further Education Project Brief Stage 9 Clare 17583V SN Cnoc an Ein, Ennis Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 10 Clare 19838P Gaelscoil Mhichil Chiosog Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 11 Clare 19849U Gaelscoil Donncha Rua, Sionna Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 12 Clare 19999Q Gaelscoil Ui Choimin, Cill Rois Pre Stage 1 13 Clare 20086B Ennis ETNS, Gort Rd, Ennis Site Acquisition Process 14 Clare 20245S Ennistymon NS On Site 15 Clare 20312H Raheen Wood Steiner, Tuamgraney Pre Stage 1 Mol an Óige Community National School, 16 Clare 20313J Stage 1 (Preliminary Design) Ennistymon 17 Clare 70830N Ennis Community College, Ennis On Site 18 Clare 91518F Ennistymon Post primary On Site 19 Cork 00467B Ballinspittle NS Stage 2a (Developed Sketch Scheme) 20 Cork 13779S Dromahane NS, Mallow Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 21 Cork 14052V / 17087J Kanturk BNS & SN -

Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Pages 1–9, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, July 27–31, 2011

EMNLP 2011 DIALECTS2011 Proceedings of the First Workshop on Algorithms and Resources for Modelling of Dialects and Language Varieties July 31, 2011 Edinburgh, Scotland, UK c 2011 The Association for Computational Linguistics Order copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ISBN 978-1-937284-17-6 / 1-937284-17-4 ii Introduction Language varieties (and specifically dialects) are a primary means of expressing a person’s social affiliation and identity. Hence, computer systems that can adapt to the user by displaying a familiar socio-cultural identity are expected to raise the acceptance within certain contexts and target groups dramatically. Although the currently prevailing statistical paradigm has made possible major achievements in many areas of natural language processing, the applicability of the available methods is generally limited to major languages / standard varieties, to the exclusion of dialects or varieties that substantially differ from the standard. While there are considerable initiatives dealing with the development of language resources for minor languages, and also reliable methods to handle accents of a given language, i.e., for applications like speech synthesis or recognition, the situation for dialects still calls for novel approaches, methods and techniques to overcome or circumvent the problem of data scarcity, but also to enhance and strengthen the standing that language varieties and dialects have in natural language processing technologies, as well as in interaction technologies that build upon the former. What made us think that a such a workshop would be a fruitful enterprise was our conviction that only joint efforts of researchers with expertise in various disciplines can bring about progress in this field. -

Defining the Archaeological Resource on the Isle of Harris

Colls and Hunter: Archaeological Resource on Harris DEFINING THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCE ON THE ISLE OF HARRIS An assessment of the impact of environmental factors and topography on the identification of buried remains KEVIN COLLS University of Birmingham <[email protected]> and JOHN HUNTER University of Birmingham <[email protected]> The modern itch after the knowledge of foreign places is so prevalent that the generality of mankind bestow little thought or time upon the place of their nativity. It is become customary in those of quality to travel young into foreign countries, whilst they are absolute strangers at home. (Martin Martin, 1707 - in Monro, D [ed] 2002: 2) Abstract Recognition of the richness and diversity of Scottish coastal archaeology has been one of the most important developments in the study of the archaeology of Scotland during recent times. The Isle of Harris, however, has been left behind. Perhaps due to its lack of upstanding archaeological monuments, or because of its harsh terrain – steep mountains, secluded valleys and deep machair (blown sand) dunes – little research has been undertaken to characterise the archaeological resource of the island and how this might be integrated into the wider trends of past human activity in the Western Isles. This paper introduces some of the preliminary results from a long-standing archaeological research project on Harris and offers a new insight into the archaeological and cultural resource of this island. The unique geological, topographical and geomorphological characteristics will be outlined and explored, with particular reference to how these factors have impacted upon the recognition of buried archaeological remains. -

Shopkindly That Has Been Missed, Notify the Business and Give Them the Opportunity to Remedy It Rather Than Posting on Social Media

SPECIAL FEATURE: Life Less Ordinary Living in a pandemic People from around West Cork share their experiences. www.westcorkpeople.ie & www.westcorkfridayad.ie October 2 – October 30, 2020, Vol XVI, Edition 218 FREE Old Town Hall, McCurtain Hill, Clonakilty, Co. Cork. E: [email protected] P: 023 8835698 SILENCE IS GOLDEN. NEW PEUGEOT e-208 FULL ELECTRIC From Direct Provision to Cork Persons of the Month: Izzeddeen and wife Eman Alkarajeh left direct provision in Cork and, together with their four children, overcame all odds to build a new life and successful Palestinian food business in Cork. They are pictured at their Cork Persons of Month award presentation with (l-r) Manus O’Callaghan and award organiser, George Duggan, Cork Crystal. Picture: Tony O’Connell Photography. *Offer valid until the end of August. CLARKE BROS LTD Main Peugeot Dealer, Clonakilty Road, Bandon, Co. Cork. Clune calls on Government to “mind our air routes” Tel: 023-8841923CLARKE BROS Web: www.clarkebrosgroup.ie ction is needed on the Avia- Irish Aviation Sector to recover from but also to onward flights through the to Ireland’s economy and its economic (BANDON) LTD tion Recovery Taskforce Re- the impact of Covid 19. One of the international airline hubs as well as recovery. Main Peugeot Dealers port to ensure we have strong recommendations of the Aviation excellent train access across Europe. The report said that a stimulus Clonakilty Road, Aregional airports post-Covid. This Recovery Taskforce Report was to MEP Clune added: “This is a very package should be put in place con- is according to Ireland South MEP provide a subvention per passenger difficult time for our airlines and air- currently for each of Cork, Shannon, Bandon Deirdre Clune who said it should be at Cork, Shannon and other Regional ports but we must ensure that they get Ireland West, Kerry and Donegal Co. -

The Irish Language and the Irish Legal System:- 1922 to Present

The Irish Language and The Irish Legal System:- 1922 to Present By Seán Ó Conaill, BCL, LLM Submitted for the Award of PhD at the School of Welsh at Cardiff University, 2013 Head of School: Professor Sioned Davies Supervisor: Professor Diarmait Mac Giolla Chríost Professor Colin Williams 1 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… 2 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… -

Murtagh, Lelia Teaching and Learning Irish in Primary School

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 432 150 FL 025 909 AUTHOR Harris, John; Murtagh, Lelia TITLE Teaching and Learning Irish in Primary School: A Review of Research and Development. INSTITUTION Institiuid Teangeolaiochta Eireann (Ireland). ISBN ISBN-0-946452-96-2 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 533p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Reports - Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC22 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Art Education; Change Strategies; Classroom Observation Techniques; Communicative Competence (Languages) ;Curriculum Design; Curriculum Development; Educational Change; Elementary Education; Foreign Countries; *Heritage Education; Instructional Materials; *Irish; *Language of Instruction; *Language Research; *Native Language Instruction; Oral Language; Science Instruction; Second Language Instruction; *Second Languages; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Content Area Teaching; *Ireland ABSTRACT Three studies concerning the-teaching of Irish in elementary schools in Ireland are presented and the implications of their findings for Irish instruction are examined. The first study described the range of conditions under which spoken Irish is taught and learned by studying a number of diverse classes, describe the teaching and learning of Irish in greater detail and from more perspectives, and develop instruments and observation procedures for collecting this new data. The second study was intended to produce guidelines and sample instructional materials for an elementary school Irish language program usiag a communicative approach. The third project involved researchers working regularly with 50 third- and fourth-grade teachers over a two-year period to develop full courses in science and art taught through the medium of Irish. Substantial documentation of the three studies is appended. (Contains 307 references.) (MSE) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

I IRISH MEDIUM EDUCATION

IRISH MEDIUM EDUCATION: COGNITIVE SKILLS, LINGUISTIC SKILLS, AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS IRISH. IVAN ANTHONY KENNEDY PhD COLLEGE OF EDUCATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING, BANGOR UNIVERSITY 2012 i In memory of Tony. No one speaks English, and everything's broken, and my Stacys are soaking wet. ~Tom Waits, Tom Traubert's Blues ii There’s a ghost of another language shadow-dancing under my words. A phantom tongue that unravels like liquor, inspires like song. ~Sharanya Manivannann, First Language Education is simply the soul of a society as it passes from one generation to another. ~G.K. Chesterton iii Acknowledgements First, and foremost, I thank my supervisor, Dr. Enlli Thomas, for all the guidance over the years. Thank you Enlli for all your constructive and friendly support and for helping me to find and embark upon the right paths throughout this project. Your immense diligence, encouragement, and support went beyond measure and I will be forever grateful for the opportunities that you gave me. From start to finish, working with you on this project was an absolute pleasure. I also thank An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta & Gaelscolaíochta for their financial support in funding this project which made its undertaking possible. Thank you Pól Ó Cainin and Muireann Ní Mhóráin for your help. I thank Siân Wyn Lloyd-Williams for all the moral and academic support throughout the project. Your input is truly valued, helped to keep me grounded, and made the project more fun and less stressful than it might otherwise have been. Additionally, I thank Dave Lane for his expertise in creating the Flanker tasks and the Sustained Attention to Response Task computer programs, Gwyn Lewis and Jean Ware for academic assistance and feedback, Beth Lye and Mirain Rhys for scoring children’s written tests, and Raymond Byrne and Ross Byrne for helping to create and pilot the Irish vocabulary tests. -

A'chleit (Argyll), A' Chleit

Iain Mac an Tàilleir 2003 1 A'Chleit (Argyll), A' Chleit. "The mouth of the Lednock", an obscure "The cliff or rock", from Norse. name. Abban (Inverness), An t-Àban. Aberlemno (Angus), Obar Leamhnach. “The backwater” or “small stream”. "The mouth of the elm stream". Abbey St Bathans (Berwick). Aberlour (Banff), Obar Lobhair. "The abbey of Baoithean". The surname "The mouth of the noisy or talkative stream". MacGylboythin, "son of the devotee of Aberlour Church and parish respectively are Baoithean", appeared in Dumfries in the 13th Cill Drostain and Sgìre Dhrostain, "the century, but has since died out. church and parish of Drostan". Abbotsinch (Renfrew). Abernethy (Inverness, Perth), Obar Neithich. "The abbot's meadow", from English/Gaelic, "The mouth of the Nethy", a river name on lands once belonging to Paisley Abbey. suggesting cleanliness. Aberarder (Inverness), Obar Àrdair. Aberscross (Sutherland), Abarsgaig. "The mouth of the Arder", from àrd and "Muddy strip of land". dobhar. Abersky (Inverness), Abairsgigh. Aberargie (Perth), Obar Fhargaidh. "Muddy place". "The mouth of the angry river", from fearg. Abertarff (Inverness), Obar Thairbh. Aberbothrie (Perth). "The mouth of the bull river". Rivers and "The mouth of the deaf stream", from bodhar, stream were often named after animals. “deaf”, suggesting a silent stream. Aberuchill (Perth), Obar Rùchaill. Abercairney (Perth). Although local Gaelic speakers understood "The mouth of the Cairney", a river name this name to mean "mouth of the red flood", from càrnach, meaning “stony”. from Obar Ruadh Thuil, older evidence Aberchalder (Inverness), Obar Chaladair. points to this name containing coille, "The mouth of the hard water", from caled "wood", with similarities to Orchill. -

Irish in Primary Schools Long Term National Trends in Achievement

IPST Cover by DOE 6/19/06 9:35 AM Page 1 Long-Term National Trends in Achievement National Trends Long-Term Irish in Primary Schools: Irish in Primary Schools Long-Term National Trends in Achievement by JOHN HARRIS TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN Patrick Forde Educational Research Centre Peter Archer Educational Research Centre Siobhán Nic Fhearaile Institiúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann Mary O’Gorman Educational Research Centre J. HARRIS S. Nic Fhearaile • M. O’Gorman • P. Forde • P. Archer • P. Forde • P. ISBN 0-0000-0000-X Irish in Primary Schools Long-Term National Trends in Achievement by JOHN HARRIS TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN Patrick Forde Educational Research Centre Peter Archer Educational Research Centre Siobhán Nic Fhearaile Institiúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann Mary O’Gorman Educational Research Centre © 2006 Department of Education and Science Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Harris, John Irish in Primary Schools : Long-term National Trends in Achievement / John Harris . [et al.] xiv, 208p; 30 cm Includes bibliographical references. 1. Irish Language – Study and Teaching (Primary) – Ireland 2. Irish Language – Spoken Irish 2006 I Harris, John. II Title 375.415 Designed by TOTAL PD Printed by Brunswick Press Published by the Stationery Office, Dublin To be purchased directly from the Government Publications Sales Office, Sun Alliance House, Molesworth Street, Dublin 2 or by mail order from Government Publications, Postal Trade Section, 51 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2 Tel: 01-647 6834 Fax: 01-647 6843 €20.00 ISBN: Number Here iii Contents List of Tables and Figures v Acknowledgements xiv Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Achievement in Irish in ordinary schools . 3 Factors associated with achievement in Irish in ordinary schools .