Irish Parents and Gaelic- Medium Education in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSAA Secondary Schools' Cross-Country Championships Deans Comm. HS Livingston Sat. 4Th March 2017 Group D Girls 1 Anna Hedley Ma

SSAA Secondary Schools' Cross-Country Championships Deans Comm. HS Livingston Sat. 4th march 2017 Group D Girls 1 Anna Hedley Madras College 8:47 80 Whelan Harriet Milne's HS 2 Anya MacLean HS of Glasgow 9:07 81 Claudia Wight Dunbar Grammar School 3 Emma Johnson George Watson's College 9:11 82 Alex Tully Madras College 4 Valencia Wright Lenzie Academy 9:16 83 Zoe Dunn Deans Community HS 5 Bridget Harley North Berwick HS 9:39 84 Alix Donald Banff Academy 6 Zoe Flower Hutchesons' Grammar School 9:42 85 Esther Jamieson Eastwood HS 7 Zara Kennedy HS of Glasgow 9:44 86 Taylor McNamara St Andrew's and St Bride's HS 8 Julia Cash Hutchesons' Grammar School 9:45 87 C Campbell Hutchesons' Grammar School 9 Mairi Craig Stirling HS 9:46 88 Isla Booth Dollar Academy 10 Isla Ward St Ninian's HS (Giff.) 9:47 89 Tina Kelly Fortrose Academy 11 Abi Hammerman Port Glasgow HS 9:49 90 Olivia Schenini Hutchesons' Grammar School 12 Rachel Muir Renfrew HS 9:49 91 Sophie Henderson Williamwood HS 13 Molli Robb St Mungo's RC HS (Falkirk) 9:49 92 Millie Wilson Strathallan School 14 Isla Cooper Annan Academy 9:50 93 Eva Bell St Andrew's Academy (Paisley) 15 Rose Ryan HS of Dundee 9:50 94 Alice Fordyce Strathallan School 16 Adele Gillespie Alford Academy 9:59 95 Kara Reynolds St Ambrose HS 17 Abbie Kirwan St Andrew's and St Bride's HS 10:20 96 Katie MacDougall Banff Academy 18 Orla Doherty Douglas Academy 10:20 97 Akira West Dollar Academy 19 Esme Thoms Bell Baxter HS 10:22 98 Abbey Hart Glasgow Gaelic School 20 Grace MacLean Douglas Academy 10:24 99 Millie Shuttleworth -

Falkirk Wheel, Scotland

Falkirk Wheel, Scotland Jing Meng Xi Jing Fang Natasha Soriano Kendra Hanagami Overview Magnitudes & Costs Project Use and Social and Economic Benefits Technical Issues and Innovations Social Problems and Policy Challenges Magnitudes Location: Central Scotland Purpose: To connecting the Forth and Clyde canal with the Union canal. To lift boats from a lower canal to an upper canal Magnitudes Construction Began: March 12, 1999 Officially at Blairdardie Road in Glasgow Construction Completed: May 24, 2002 Part of the Millennium Link Project undertaken by British Waterways in Scotland To link the West and East coasts of Scotland with fully navigable waterways for the first time in 35 years Magnitudes The world’s first and only rotating boat wheel Two sets of axe shaped arms Two diametrically opposed waterwater-- filled caissons Magnitudes Overall diameter is 35 meters Wheel can take 4 boats up and 4 boats down Can overcome the 24m vertical drop in 15 minute( 600 tones) To operate the wheel consumes just 1.5 kilowattkilowatt--hourshours in rotation Costs and Prices Total Cost of the Millennium Link Project: $123 M $46.4 M of fund came from Nation Lottery Falkirk Wheel Cost: $38.5 M Financing Project was funded by: British Waterways Millennium Commission Scottish Enterprise European Union Canalside local authorities Fares for Wheel The Falkirk Wheel Experience Tour: Adults $11.60 Children $6.20 Senior $9.75 Family $31.20 Social Benefits Proud Scots Queen of Scotland supported the Falkirk Wheel revived an important -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Police Division.Dot

Safer Communities Directorate Police Powers Unit T: 0131-244-2355 E: [email protected] T Johnson Via email ___ Our ref: FOI/13/00538 26 April 2013 Dear T Johnson Thank you for your email dated 5 April, in which you make a request under the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 (FOISA) for: 1) Information about the make, model and muzzle energy of the gun used in the fatal shooting of a child in Easterhouse in 2005; 2) Details of the number of meetings, those involved in said meetings and the minutes of meetings regarding the Scottish Firearms Consultative Panel (SFCP); 3) Information regarding land that provides a safe shooting ground that is as accessible as a member of the public’s own garden, or clubs that offer open access to the general public; and 4) Details of any ranges that people can freely rent similar to other countries, in the central belt area of Scotland. In relation to your request number 1), I have assumed that you are referring specifically to the death of Andrew Morton. Following a search of our paper and electronic records, I have established that the information you have requested is not held by the Scottish Government. You may wish to contact either the police or Procurator Fiscal Service, who may be able to provide this information. Contact details for Police Scotland can be found online at www.scotland.police.uk/access-to-information/freedom-of-information/, and for the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service at www.crownoffice.gov.uk/FOI/Freedom-Information- and-Environmental-Information-Regulations. -

Scottish Register of Tartans Bill (SP Bill 76 ) As Introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 27 September 2006

This document relates to the Scottish Register of Tartans Bill (SP Bill 76 ) as introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 27 September 2006 SCOTTISH REGISTER OF TARTANS BILL —————————— POLICY MEMORANDUM INTRODUCTION 1. This document relates to the Scottish Register of Tartans Bill introduced in the S cottish Parliament on 27 September 2006 . It has been prepared by Jamie McGrigor MSP, the member in charge of the Bill with the assistance of the Parliament’s Non Executive Bills Unit to satisfy Rul e 9.3.3(c ) of the Parliament ’s Standing Orders. The contents are entirely the responsibility of the member and have not been endorsed by the Parliament. Explanatory Notes and other accompanying documents are published separately as SP Bill 76 –EN. POLICY OBJECTIVES OF THE BILL Overview 2. The Bill provides for the establishment of a Register of Tartans and for the appointment of a Keeper to administer and maintain the Register . 3. The stated purpose of the Bill is to create an archive of tartans for reference and information purposes. It is also hoped that the existence of the Register will help promote tartan generally by providing a central point of focus for those interested in tartan . Key objective of the Bill 4. The object ive of the Bill is to create a not for profit Scottish Registe r. While registration is voluntary the Register will function as both a current record and a national archive and will be accessible to the public. Registration does not interfere with existing rights in tartan or create any additional rights and the purpose of registration is purely to create, over time, a central, authoritative source of information on tartan designs. -

The$Irish$Language$And$Everyday$Life$ In#Derry!

The$Irish$language$and$everyday$life$ in#Derry! ! ! ! Rosa!Siobhan!O’Neill! ! A!thesis!submitted!in!partial!fulfilment!of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of! Doctor!of!Philosophy! The!University!of!Sheffield! Faculty!of!Social!Science! Department!of!Sociological!Studies! May!2019! ! ! i" " Abstract! This!thesis!explores!the!use!of!the!Irish!language!in!everyday!life!in!Derry!city.!I!argue!that! representations!of!the!Irish!language!in!media,!politics!and!academic!research!have! tended!to!overKidentify!it!with!social!division!and!antagonistic!cultures!or!identities,!and! have!drawn!too!heavily!on!political!rhetoric!and!a!priori!assumptions!about!language,! culture!and!groups!in!Northern!Ireland.!I!suggest!that!if!we!instead!look!at!the!mundane! and!the!everyday!moments!of!individual!lives,!and!listen!to!the!voices!of!those!who!are! rarely!heard!in!political!or!media!debate,!a!different!story!of!the!Irish!language!emerges.! Drawing!on!eighteen!months!of!ethnographic!research,!together!with!document!analysis! and!investigation!of!historical!statistics!and!other!secondary!data!sources,!I!argue!that! learning,!speaking,!using,!experiencing!and!relating!to!the!Irish!language!is!both!emotional! and!habitual.!It!is!intertwined!with!understandings!of!family,!memory,!history!and! community!that!cannot!be!reduced!to!simple!narratives!of!political!difference!and! constitutional!aspirations,!or!of!identity!as!emerging!from!conflict.!The!Irish!language!is! bound!up!in!everyday!experiences!of!fun,!interest,!achievement,!and!the!quotidian!ebbs! and!flows!of!daily!life,!of!getting!the!kids!to!school,!going!to!work,!having!a!social!life!and! -

Innovative Routes to Learning S@S Accelerate 2013 Programme

Innovative Routes to Learning S@S Accelerate 2013 Programme Report for Women’s Engineering Society Contents Executive Summary ………………....………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Programme Overview……………………………………………………………………………………………....... 6 Programme Aims..………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Summary of Programme Activity………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Programme Participants…………………………………………………………………………………………...... 8 WES-funded Participant Evaluation 11 Qualitative Data……………………………………………………………………………………. 11 Quantitative Data………………….………………………………………………………………. 14 Junior Mentor Evaluation…………………..….……………………………………………………………………. 21 2011 Programme Participants: Applications to Strathclyde…….…………………………………… 25 2012 Participants: Applications to Strathclyde Engineering Faculty…………………………….. 28 Appendix 1: Funders of the 2013 Programme…….……………………………………………………….. 30 Appendix 2: Contributors to the 2013 Programme…….……………………………………………….. 31 Appendix 3: 2013 Participating Schools by Local Authority…….…………………………………… 32 2 Executive Summary Programme Overview 2013 saw the 5th year of the S@S Accelerate programme, run by the Innovative Routes to Learning (IRL) Unit within the School of Education at the University of Strathclyde. The programme aims to provide S5 & S6 school pupils with a targeted focus on their chosen area of potential University study. Participants chose from 12 one-week subject-specific Challenge programmes and were led through these by undergraduate and postgraduate student mentors; 61 from the University of Strathclyde and five from the University -

Mapping Farmland Wader Distributions and Population Change to Identify Wader Priority Areas for Conservation and Management Action

Mapping farmland wader distributions and population change to identify wader priority areas for conservation and management action Scott Newey1*, Debbie Fielding1, and Mark Wilson2 1. The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, AB15 8QH 2. The British Trust for Ornithology Scotland, Stirling, FK9 4NF * [email protected] Introduction Many birds have declined across Scotland and the UK as a whole (Balmer et al. 2013, Eaton et al. 2015, Foster et al. 2013, Harris et al. 2017). These include five species of farmland wader; oystercatcher, lapwing, curlew, redshank and snipe. All of these have all been listed as either red or amber species on the UK list of birds of conservation concern (Harris et al. 2017, Eaton et al. 2015). Between 1995 and 2016 both lapwing and curlew declined by more than 40% in the UK (Harris et al. 2017). The UK harbours an estimated 19-27% of the curlew’s global breeding population, and the curlew is arguably the most pressing bird conservation challenge in the UK (Brown et al. 2015). However, the causes of wader declines likely include habitat loss, alteration and homogenisation (associated strongly with agricultural intensification), and predation by generalist predators (Brown et al. 2015, van der Wal & Palmer 2008, Ainsworth et al. 2016). There has been a concerted effort to reverse wader declines through habitat management, wader sensitive farming practices and predator control, all of which are likely to benefit waders at the local scale. However, the extent and severity of wader population declines means that large scale, landscape level, collaborative actions are needed if these trends are to be halted or reversed across much of these species’ current (and former) ranges. -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction. -

A Revitalization Study of the Irish Language

TAKING THE IRISH PULSE: A REVITALIZATION STUDY OF THE IRISH LANGUAGE Donna Cheryl Roloff Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2015 APPROVED: John Robert Ross, Committee Chair Kalaivahni Muthiah, Committee Member Willem de Reuse, Committee Member Patricia Cukor-Avila, Director of the Linguistics Program Greg Jones, Interim Dean of College of Information Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Roloff, Donna Cheryl. Taking the Irish Pulse: A Revitalization Study of the Irish Language. Master of Arts (Linguistics), December 2015, 60 pp., 22 tables, 3 figures, references, 120 titles. This thesis argues that Irish can and should be revitalized. Conducted as an observational case study, this thesis focuses on interviews with 72 participants during the summer of 2013. All participants live in the Republic of Ireland or Northern Ireland. This thesis investigates what has caused the Irish language to lose power and prestige over the centuries, and which Irish language revitalization efforts have been successful. Findings show that although, all-Irish schools have had a substantial growth rate since 1972, when the schools were founded, the majority of Irish students still get their education through English- medium schools. This study concludes that Irish will survive and grow in the numbers of fluent Irish speakers; however, the government will need to further support the growth of the all-Irish schools. In conclusion, the Irish communities must take control of the promotion of the Irish language, and intergenerational transmission must take place between parents and their children. Copyright 2015 by Donna Cheryl Roloff ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND THE DETERIORATION 13 OF THE IRISH LANGUAGE CHAPTER 3 IRISH SHOULD BE REVIVED 17 CHAPTER 4 IRISH CAN BE REVIVED 28 CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSION 44 REFERENCES 53 iii LIST OF TABLES Page 1. -

Scottish Re-Use Mapping and Sector Analysis Report

Scottish re-use mapping and sector analysis Zero Waste Scotland works with businesses, individuals, communities and local authorities to help them reduce waste, recycle more and use resources sustainably. Find out more at www.zerowastescotland.org.uk Written by: Billy Harris, Stuart Clouth, Coralline Guillon, Caroline Lee- Smith Executive summary The revised Waste Framework Directive requires all EU Member States to produce a National Waste Prevention Plan by December 2013. The Scottish Government has shown a strong commitment in this area, committing itself to a strategy that seeks to prevent waste and to channel products into re-use where possible. The Scottish Government is supported by Zero Waste Scotland, which is seeking to provide support to encourage the growth of the re-use economy in Scotland. Zero Waste Scotland commissioned Resource Futures to conduct a mapping study of re-use organisations across Scortland, with the aim of improving knowledge of the sector and establishing the baseline level of re-use activity. This will be used to inform any future programme of support. The key elements of of the research were: A mapping exercise, identifying re-use organisations in Scotland by type and location. Conduct a questionnaire survey to improve understanding of the activities and support needs of re-use organisations. A series of in-depth interviews with re-use organisations to gather more qualitative information on market conditions and strategic issues affecting re-use. Interviews with council representatives to assess local authority attitudes towards re-use and explore options for local authority involvement and partnership working to divert items from the municipal waste stream for re-use. -

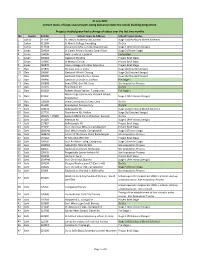

31 July 2021 Current Status of Large-Scale Projects Being Delivered Under the School Building Programme

31 July 2021 Current status of large-scale projects being delivered under the school building programme. Projects shaded green had a change of status over the last two months No. County Roll No School Name & Address School Project Status 1 Carlow 61120E St. Mary's Academy CBS, Carlow Stage 2a (Developed Sketch Scheme) 2 Carlow 61130H St Mary's College, Knockbeg On Site 3 Carlow 61150N Presentation/De La Salle, Bagnelstown Stage 1 (Preliminary Design) 4 Cavan 08490N St Clare's Primary School, Cavan Town Stage 3 (Tender Stage) 5 Cavan 19439B Holy Family SS, Cootehill Completed 6 Cavan 20026G Gaelscoil Bhreifne Project Brief Stage 7 Cavan 70360C St Mogues College Project Brief Stage 8 Cavan 76087R Cavan College of Further Education Project Brief Stage 9 Clare 17583V SN Cnoc an Ein, Ennis Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 10 Clare 19838P Gaelscoil Mhichil Chiosog Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 11 Clare 19849U Gaelscoil Donncha Rua, Sionna Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 12 Clare 19999Q Gaelscoil Ui Choimin, Cill Rois Pre Stage 1 13 Clare 20086B Ennis ETNS, Gort Rd, Ennis Site Acquisition Process 14 Clare 20245S Ennistymon NS On Site 15 Clare 20312H Raheen Wood Steiner, Tuamgraney Pre Stage 1 Mol an Óige Community National School, 16 Clare 20313J Stage 1 (Preliminary Design) Ennistymon 17 Clare 70830N Ennis Community College, Ennis On Site 18 Clare 91518F Ennistymon Post primary On Site 19 Cork 00467B Ballinspittle NS Stage 2a (Developed Sketch Scheme) 20 Cork 13779S Dromahane NS, Mallow Stage 2b (Detailed Design) 21 Cork 14052V / 17087J Kanturk BNS & SN