This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cytokine Nomenclature

RayBiotech, Inc. The protein array pioneer company Cytokine Nomenclature Cytokine Name Official Full Name Genbank Related Names Symbol 4-1BB TNFRSF Tumor necrosis factor NP_001552 CD137, ILA, 4-1BB ligand receptor 9 receptor superfamily .2. member 9 6Ckine CCL21 6-Cysteine Chemokine NM_002989 Small-inducible cytokine A21, Beta chemokine exodus-2, Secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine, SLC, SCYA21 ACE ACE Angiotensin-converting NP_000780 CD143, DCP, DCP1 enzyme .1. NP_690043 .1. ACE-2 ACE2 Angiotensin-converting NP_068576 ACE-related carboxypeptidase, enzyme 2 .1 Angiotensin-converting enzyme homolog ACTH ACTH Adrenocorticotropic NP_000930 POMC, Pro-opiomelanocortin, hormone .1. Corticotropin-lipotropin, NPP, NP_001030 Melanotropin gamma, Gamma- 333.1 MSH, Potential peptide, Corticotropin, Melanotropin alpha, Alpha-MSH, Corticotropin-like intermediary peptide, CLIP, Lipotropin beta, Beta-LPH, Lipotropin gamma, Gamma-LPH, Melanotropin beta, Beta-MSH, Beta-endorphin, Met-enkephalin ACTHR ACTHR Adrenocorticotropic NP_000520 Melanocortin receptor 2, MC2-R hormone receptor .1 Activin A INHBA Activin A NM_002192 Activin beta-A chain, Erythroid differentiation protein, EDF, INHBA Activin B INHBB Activin B NM_002193 Inhibin beta B chain, Activin beta-B chain Activin C INHBC Activin C NM005538 Inhibin, beta C Activin RIA ACVR1 Activin receptor type-1 NM_001105 Activin receptor type I, ACTR-I, Serine/threonine-protein kinase receptor R1, SKR1, Activin receptor-like kinase 2, ALK-2, TGF-B superfamily receptor type I, TSR-I, ACVRLK2 Activin RIB ACVR1B -

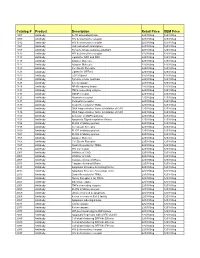

Comprehensive Product List

Catalog # Product Description Retail Price OEM Price 1007 Antibody IL-1R associated kinase 225/100ug 125/100ug 1009 Antibody HIV & chemokine receptor 225/100ug 125/100ug 1012 Antibody HIV & chemokine receptor 225/100ug 125/100ug 1021 Antibody JAK activated transcription 225/100ug 125/100ug 1107 Antibody Tyrosine kinase substrate p62DOK 225/100ug 125/100ug 1112 Antibody HIV & chemokine receptor 225/100ug 125/100ug 1113 Antibody Ligand for DR4 and DR5 225/100ug 125/100ug 1115 Antibody Adapter Molecule 225/100ug 125/100ug 1117 Antibody Adapter Molecule 225/100ug 125/100ug 1120 Antibody Cell Death Receptor 225/100ug 125/100ug 1121 Antibody Ligand for GFRa-2 225/100ug 125/100ug 1123 Antibody CCR3 ligand 225/100ug 125/100ug 1125 Antibody Tyrosine kinase substrate 225/100ug 125/100ug 1128 Antibody A new caspase 225/100ug 125/100ug 1129 Antibody NF-kB inducing kinase 225/100ug 125/100ug 1131 Antibody TNFa converting enzyme 225/100ug 125/100ug 1133 Antibody GDNF receptor 225/100ug 125/100ug 1135 Antibody Neurturin receptor 225/100ug 125/100ug 1137 Antibody Persephin receptor 225/100ug 125/100ug 1139 Antibody Death Receptor for TRAIL 225/100ug 125/100ug 1141 Antibody DNA fragmentation factor & Inhibitor of CAD 225/100ug 125/100ug 1148 Antibody DNA fragmentation factor & Inhibitor of CAD 225/100ug 125/100ug 1150 Antibody Activator of MAPK pathway 225/100ug 125/100ug 1151 Antibody Apoptosis Signal-regulation Kinase 225/100ug 125/100ug 1156 Antibody FLICE inhibitory protein 225/100ug 125/100ug 1158 Antibody Cell Death Receptor 225/100ug 125/100ug 1159 -

Development and Validation of a Protein-Based Risk Score for Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Patients with Stable Coronary Heart Disease

Supplementary Online Content Ganz P, Heidecker B, Hveem K, et al. Development and validation of a protein-based risk score for cardiovascular outcomes among patients with stable coronary heart disease. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5951 eTable 1. List of 1130 Proteins Measured by Somalogic’s Modified Aptamer-Based Proteomic Assay eTable 2. Coefficients for Weibull Recalibration Model Applied to 9-Protein Model eFigure 1. Median Protein Levels in Derivation and Validation Cohort eTable 3. Coefficients for the Recalibration Model Applied to Refit Framingham eFigure 2. Calibration Plots for the Refit Framingham Model eTable 4. List of 200 Proteins Associated With the Risk of MI, Stroke, Heart Failure, and Death eFigure 3. Hazard Ratios of Lasso Selected Proteins for Primary End Point of MI, Stroke, Heart Failure, and Death eFigure 4. 9-Protein Prognostic Model Hazard Ratios Adjusted for Framingham Variables eFigure 5. 9-Protein Risk Scores by Event Type This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/02/2021 Supplemental Material Table of Contents 1 Study Design and Data Processing ......................................................................................................... 3 2 Table of 1130 Proteins Measured .......................................................................................................... 4 3 Variable Selection and Statistical Modeling ........................................................................................ -

Defining Molecular Adjuvant Effects on Human B Cell Subsets

DEFINING MOLECULAR ADJUVANT EFFECTS ON HUMAN B CELL SUBSETS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES (TROPICAL MEDICINE) August 2019 By Jourdan Posner Dissertation Committee: Sandra P. Chang, Chairperson George Hui Saguna Verma William Gosnell Alan Katz ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my PhD advisor and mentor, Dr. Sandra Chang. Her passion for science, scientific rigor, and inquisitive nature have been an inspiration to me. I am very grateful for her continuous support and mentorship. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. George Hui, Dr. Saguna Verma, Dr. William Gosnell, and Dr. Alan Katz, for their advice and support on this dissertation work. To my parasitology “dads”, Dr. Kenton Kramer and Dr. William Gosnell, I am forever grateful for all of the opportunities you’ve given to me. Your mentorship has guided me through the doctoral process and helped me to maintain “homeostasis”. Last, but not least, I’d like to thank my parents and brother who have been so supportive throughout my entire graduate career. I greatly appreciate all of the encouraging words and for always believing in me. And to my future husband, Ian, I could not have completed this dissertation work without your endless support. You are my rock. ii ABSTRACT Recent advances in vaccine development include the incorporation of novel adjuvants to increase vaccine immunogenicity and efficacy. Pattern recognition receptor (PRR) ligands are of particular interest as vaccine adjuvants. -

A Comparison of the Cytoplasmic Domains of the Fas Receptor and the P75 Neurotrophin Receptor

Cell Death and Differentiation (1999) 6, 1133 ± 1142 ã 1999 Stockton Press All rights reserved 13509047/99 $15.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/cdd A comparison of the cytoplasmic domains of the Fas receptor and the p75 neurotrophin receptor 1,2 1,2 1 ,1 H Kong , AH Kim , JR Orlinick and MV Chao* Introduction 1 Molecular Neurobiology Program, Skirball Institute, New York University The p75 receptor is the founding member of the TNF Medical Center, 540 First Avenue, New York, NY 10016, USA receptor superfamily.1 Structural features shared by several 2 The ®rst two authors contributed equally to this study members of this family include a cysteine-rich extracellular * Corresponding author: MV Chao, Molecular Neurobiology Program, Skirball domain repeated two to six times and an intracellular motif Institute, New York University Medical Center, 540 First Avenue, New York, NY termed the `death domain'. The term `death domain' was 10016, USA. Tel: +1 212-263-0722; Fax: +1 212-263-0723; E-mail: [email protected] coined from its functional role in mediating apoptosis, particularly via the p55 TNF receptor and FasR.2,3 The Received 15.7.98; revised 20.8.99; accepted 23.8.99 death domain is a protein association motif4,5 that binds to Edited by C Thiele cytoplasmic proteins, which can trigger the caspase protease cascade or other signal transduction pathways. Multiple adaptor and death effector proteins that bind to the Abstract death domains of the p55 TNF and Fas receptors have The p75 neurotrophic receptor (p75) shares structural been identified. -

Cell Structure & Function

Cell Structure & Function Antibodies and Reagents BioLegend is ISO 13485:2016 Certified Toll-Free Tel: (US & Canada): 1.877.BIOLEGEND (246.5343) Tel: 858.768.5800 biolegend.com 02-0012-03 World-Class Quality | Superior Customer Support | Outstanding Value Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................................3 Cell Biology Antibody Validation .............................................................................................................................................4 Cell Structure/ Organelles ..........................................................................................................................................................8 Cell Development and Differentiation ................................................................................................................................10 Growth Factors and Receptors ...............................................................................................................................................12 Cell Proliferation, Growth, and Viability...............................................................................................................................14 Cell Cycle ........................................................................................................................................................................................16 Cell Signaling ................................................................................................................................................................................18 -

Death Receptor 6 Contributes to Autoimmunity in Lupus-Prone Mice

ARTICLE Received 25 Oct 2015 | Accepted 15 Nov 2016 | Published 3 Jan 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms13957 OPEN Death receptor 6 contributes to autoimmunity in lupus-prone mice Daisuke Fujikura1,2,3, Masahiro Ikesue2, Tsutomu Endo2, Satoko Chiba1,3, Hideaki Higashi1 & Toshimitsu Uede2 Expansion of autoreactive follicular helper T (Tfh) cells is tightly restricted to prevent induction of autoantibody-dependent immunological diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Here we show expression of an orphan immune regulator, death receptor 6 (DR6/TNFRSF21), on a population of Tfh cells that are highly expanded in lupus-like disease progression in mice. Genome-wide screening reveals an interaction between syndecan-1 and DR6 resulting in immunosuppressive functions. Importantly, syndecan-1 is expressed specifically on autoreactive germinal centre (GC) B cells that are critical for maintenance of Tfh cells. Syndecan-1 expression level on GC B cells is associated with Tfh cell expansion and disease progression in lupus-prone mouse strains. In addition, Tfh cell suppression by DR6-specific monoclonal antibody delays disease progression in lupus-prone mice. These findings suggest that the DR6/syndecan-1 axis regulates aberrant GC reactions and could be a therapeutic target for autoimmune diseases such as SLE. 1 Division of Infection and Immunity, Hokkaido University Research Center for Zoonosis Control, North-20, West-10, Kita-ku, Sapporo 001-0020, Japan. 2 Division of Molecular Immunology, Hokkaido University Institute for Genetic Medicine, North-15, West-7, Kita-ku, Sapporo 060-0815, Japan. 3 Division of Bioresources, Hokkaido University Research Center for Zoonosis Control, North-20, West-10, Kita-ku, Sapporo 001-0020, Japan. -

Apoptosis of Tumor-Infiltrating T Lymphocytes: a New Immune

Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy (2019) 68:835–847 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-018-2269-y FOCUSSED RESEARCH REVIEW Apoptosis of tumor‑infiltrating T lymphocytes: a new immune checkpoint mechanism Jingjing Zhu1,2,3 · Pierre‑Florent Petit1,2 · Benoit J. Van den Eynde1,2,3 Received: 17 July 2018 / Accepted: 29 October 2018 / Published online: 7 November 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Immunotherapy based on checkpoint inhibitors is providing substantial clinical benefit, but only to a minority of cancer patients. The current priority is to understand why the majority of patients fail to respond. Besides T-cell dysfunction, T-cell apoptosis was reported in several recent studies as a relevant mechanism of tumoral immune resistance. Several death receptors (Fas, DR3, DR4, DR5, TNFR1) can trigger apoptosis when activated by their respective ligands. In this review, we discuss the immunomodulatory role of the main death receptors and how these are shaping the tumor microenviron- ment, with a focus on Fas and its ligand. Fas-mediated apoptosis of T cells has long been known as a mechanism allowing the contraction of T-cell responses to prevent immunopathology, a phenomenon known as activation-induced cell death, which is triggered by induction of Fas ligand (FasL) expression on T cells themselves and qualifies as an immune checkpoint mechanism. Recent evidence indicates that other cells in the tumor microenvironment can express FasL and trigger apoptosis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), including endothelial cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. The resulting disappearance of TIL prevents anti-tumor immunity and may in fact contribute to the absence of TIL that is typical of “cold” tumors that fail to respond to immunotherapy. -

Characterization of Chicken TNFR Superfamily Decoy Receptors, Dcr3 and Osteoprotegerinq

BBRC Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 307 (2003) 956–961 www.elsevier.com/locate/ybbrc Characterization of chicken TNFR superfamily decoy receptors, DcR3 and osteoprotegerinq Jamie T. Bridgham and Alan L. Johnson* Department of Biological Sciences and the Walther Cancer Research Center, The University of Notre Dame, P.O. Box369, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA Received 31 May 2003 Abstract Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family ligands bind to death domain-containing TNF receptors (death receptors), which can subsequently activate intracellular signaling pathways to initiate caspase activity and apoptotic cell death. Decoy receptors, without intracellular death domains, have been reported to prevent cytotoxic effects by binding to and sequestering such ligands, or by interfering with death receptor trimerization. The chicken death receptors, Fas, TNFR1, DR6, and TVB, are constitutively ex- pressed in a relatively wide variety of hen tissues. In this study, two chicken receptors with sequence homology to the mammalian decoys, DcR3 and osteoprotegerin, were identified and their pattern of expression was characterized. Unlike the previously iden- tified chicken death receptors, the newly characterized decoy receptors show comparatively limited expression among tissues, suggesting a tissue-specific function. Finally, characterization of these chicken receptors further contributes to understanding the evolutionary divergence of TNFR superfamily members among vertebrate species. Ó 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily; TNF ligands; Death receptor; Decoy receptor; Ovary; Chicken; Apoptosis Death receptors (DRs) are characterized by the pres- Alternatively, many of the death receptors are capa- ence of a variable number of extracellular cysteine-rich ble of signaling through intracellular pathways that ac- motifs that comprise the ligand binding domain, a single- tually promote cell survival. -

Membrane Trafficking of Death Receptors: Implications on Signalling

Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 14475-14503; doi:10.3390/ijms140714475 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Molecular Sciences ISSN 1422-0067 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms Review Membrane Trafficking of Death Receptors: Implications on Signalling Wulf Schneider-Brachert, Ulrike Heigl and Martin Ehrenschwender * Institute for Clinical Microbiology and Hygiene, University of Regensburg, Franz-Josef-Strauss-Allee 11, Regensburg 93053, Germany; E-Mails: [email protected] (W.S.-B.); [email protected] (U.H.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-941-944-6440; Fax: +49-941-944-6415. Received: 9 May 2013; in revised form: 19 June 2013 / Accepted: 27 June 2013 / Published: 11 July 2013 Abstract: Death receptors were initially recognised as potent inducers of apoptotic cell death and soon ambitious attempts were made to exploit selective ignition of controlled cellular suicide as therapeutic strategy in malignant diseases. However, the complexity of death receptor signalling has increased substantially during recent years. Beyond activation of the apoptotic cascade, involvement in a variety of cellular processes including inflammation, proliferation and immune response was recognised. Mechanistically, these findings raised the question how multipurpose receptors can ensure selective activation of a particular pathway. A growing body of evidence points to an elegant spatiotemporal regulation of composition and assembly of the receptor-associated signalling complex. Upon ligand binding, receptor recruitment in specialized membrane compartments, formation of receptor-ligand clusters and internalisation processes constitute key regulatory elements. In this review, we will summarise the current concepts of death receptor trafficking and its implications on receptor-associated signalling events. -

The Tumor Necrosis Factor Family: Family Conventions and Private Idiosyncrasies

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on September 26, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The Tumor Necrosis Factor Family: Family Conventions and Private Idiosyncrasies David Wallach Department of Biomolecular Sciences, The Weizmann Institute of Science, 76100 Rehovot, Israel Correspondence: [email protected] The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) cytokine family and the TNF/nerve growth factor (NGF) family of their cognate receptors together control numerous immune functions, as well as tissue- homeostatic and embryonic-development processes. These diverse functions are dictated by both shared and distinct features of family members, and by interactions of some members with nonfamily ligands and coreceptors. The spectra of their activities are further expanded by the occurrence ofthe ligandsand receptorsinboth membrane-anchored andsoluble forms, by “re-anchoring” of soluble formsto extracellular matrix components, and bysignaling initiation via intracellular domains (IDs) of both receptors and ligands. Much has been learned about shared features of the receptors as well as of the ligands; however, we still have only limited knowledge of the mechanistic basis for their functional heterogeneity and for the differences between their functions and those of similarly acting cytokines of other families. he study of protein families and their indi- but whose occurrence raises the possibility that Tvidual members contribute cooperatively to other family members participate in similar the assembly of knowledge, providing insights associations. into the features shared by family members as well as their distinctive features. The benefitof such a cooperative endeavor is lavishly demon- THE WIDE RANGE OF FUNCTIONS OF THE TNF FAMILY strated by the huge advances in understanding the mechanisms of action of the tumor necrosis There are 18 known human genes for the TNF factor (TNF) ligand and TNF/nerve growth fac- ligand family and 29 for the TNF/NGFR fami- tor receptor (NGFR) families. -

5 Adaptor Proteins in Death Receptor Signaling

Chapter 5 / Death Signal Adaptors 93 5 Adaptor Proteins in Death Receptor Signaling Nien-Jung Chen, PhD and Wen-Chen Yeh, MD, PhD SUMMARY Signal transduction induced by death receptors belonging to the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily has been an area of intensive research for the past several years. The major advances arising from these studies have been the characterization of critical signal-transducing adaptor molecules and the delineation of parallel but opposing signaling pathways, some inducing apoptosis and others promoting cell survival. An imbalance in favor of either apoptosis or cell survival can have disastrous pathological consequences, including cancer, autoimmunity, or immune deficiency. Many adaptor proteins have been reported in the literature to be involved in death receptor signaling. In this chapter, we will focus on molecules whose functions have been investigated by multiple approaches, particularly gene targeting in mice and ex vivo biochemical studies. By validating or clarifying the function of each adaptor, we hope to construct a blueprint of the various signaling channels triggered by death receptors, providing a foundation for further scientific investigations and practical therapeutic designs. INTRODUCTION Cancer biologists and oncologists have struggled for years to devise ways of eradicat- ing cancer cells while sparing normal ones. One breakthrough that has emerged during the past decade has been the investigation of the molecular mechanisms of apoptosis (1). Apoptosis is a critical physiological process that is subject to intricate regulation. Indeed, many cancers arise from the dysregulation of apoptotic or antiapoptotic signals, and such dysregulation is often attributable to mutation or altered expression of specific molecules (1,2).