DRAM Memory Controller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benchmarking the Intel FPGA SDK for Opencl Memory Interface

The Memory Controller Wall: Benchmarking the Intel FPGA SDK for OpenCL Memory Interface Hamid Reza Zohouri*†1, Satoshi Matsuoka*‡ *Tokyo Institute of Technology, †Edgecortix Inc. Japan, ‡RIKEN Center for Computational Science (R-CCS) {zohour.h.aa@m, matsu@is}.titech.ac.jp Abstract—Supported by their high power efficiency and efficiency on Intel FPGAs with different configurations recent advancements in High Level Synthesis (HLS), FPGAs are for input/output arrays, vector size, interleaving, kernel quickly finding their way into HPC and cloud systems. Large programming model, on-chip channels, operating amounts of work have been done so far on loop and area frequency, padding, and multiple types of blocking. optimizations for different applications on FPGAs using HLS. However, a comprehensive analysis of the behavior and • We outline one performance bug in Intel’s compiler, and efficiency of the memory controller of FPGAs is missing in multiple deficiencies in the memory controller, leading literature, which becomes even more crucial when the limited to significant loss of memory performance for typical memory bandwidth of modern FPGAs compared to their GPU applications. In some of these cases, we provide work- counterparts is taken into account. In this work, we will analyze arounds to improve the memory performance. the memory interface generated by Intel FPGA SDK for OpenCL with different configurations for input/output arrays, II. METHODOLOGY vector size, interleaving, kernel programming model, on-chip channels, operating frequency, padding, and multiple types of A. Memory Benchmark Suite overlapped blocking. Our results point to multiple shortcomings For our evaluation, we develop an open-source benchmark in the memory controller of Intel FPGAs, especially with respect suite called FPGAMemBench, available at https://github.com/ to memory access alignment, that can hinder the programmer’s zohourih/FPGAMemBench. -

A Modern Primer on Processing in Memory

A Modern Primer on Processing in Memory Onur Mutlua,b, Saugata Ghoseb,c, Juan Gomez-Luna´ a, Rachata Ausavarungnirund SAFARI Research Group aETH Z¨urich bCarnegie Mellon University cUniversity of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign dKing Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok Abstract Modern computing systems are overwhelmingly designed to move data to computation. This design choice goes directly against at least three key trends in computing that cause performance, scalability and energy bottlenecks: (1) data access is a key bottleneck as many important applications are increasingly data-intensive, and memory bandwidth and energy do not scale well, (2) energy consumption is a key limiter in almost all computing platforms, especially server and mobile systems, (3) data movement, especially off-chip to on-chip, is very expensive in terms of bandwidth, energy and latency, much more so than computation. These trends are especially severely-felt in the data-intensive server and energy-constrained mobile systems of today. At the same time, conventional memory technology is facing many technology scaling challenges in terms of reliability, energy, and performance. As a result, memory system architects are open to organizing memory in different ways and making it more intelligent, at the expense of higher cost. The emergence of 3D-stacked memory plus logic, the adoption of error correcting codes inside the latest DRAM chips, proliferation of different main memory standards and chips, specialized for different purposes (e.g., graphics, low-power, high bandwidth, low latency), and the necessity of designing new solutions to serious reliability and security issues, such as the RowHammer phenomenon, are an evidence of this trend. -

Advanced X86

Advanced x86: BIOS and System Management Mode Internals Input/Output Xeno Kovah && Corey Kallenberg LegbaCore, LLC All materials are licensed under a Creative Commons “Share Alike” license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ ABribuEon condiEon: You must indicate that derivave work "Is derived from John BuBerworth & Xeno Kovah’s ’Advanced Intel x86: BIOS and SMM’ class posted at hBp://opensecuritytraining.info/IntroBIOS.html” 2 Input/Output (I/O) I/O, I/O, it’s off to work we go… 2 Types of I/O 1. Memory-Mapped I/O (MMIO) 2. Port I/O (PIO) – Also called Isolated I/O or port-mapped IO (PMIO) • X86 systems employ both-types of I/O • Both methods map peripheral devices • Address space of each is accessed using instructions – typically requires Ring 0 privileges – Real-Addressing mode has no implementation of rings, so no privilege escalation needed • I/O ports can be mapped so that they appear in the I/O address space or the physical-memory address space (memory mapped I/O) or both – Example: PCI configuration space in a PCIe system – both memory-mapped and accessible via port I/O. We’ll learn about that in the next section • The I/O Controller Hub contains the registers that are located in both the I/O Address Space and the Memory-Mapped address space 4 Memory-Mapped I/O • Devices can also be mapped to the physical address space instead of (or in addition to) the I/O address space • Even though it is a hardware device on the other end of that access request, you can operate on it like it's memory: – Any of the processor’s instructions -

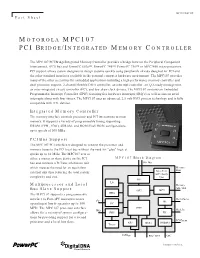

Motorola Mpc107 Pci Bridge/Integrated Memory Controller

MPC107FACT/D Fact Sheet MOTOROLA MPC107 PCI BRIDGE/INTEGRATED MEMORY CONTROLLER The MPC107 PCI Bridge/Integrated Memory Controller provides a bridge between the Peripheral Component Interconnect, (PCI) bus and PowerPC 603e™, PowerPC 740™, PowerPC 750™ or MPC7400 microprocessors. PCI support allows system designers to design systems quickly using peripherals already designed for PCI and the other standard interfaces available in the personal computer hardware environment. The MPC107 provides many of the other necessities for embedded applications including a high-performance memory controller and dual processor support, 2-channel flexible DMA controller, an interrupt controller, an I2O-ready message unit, an inter-integrated circuit controller (I2C), and low skew clock drivers. The MPC107 contains an Embedded Programmable Interrupt Controller (EPIC) featuring five hardware interrupts (IRQ’s) as well as sixteen serial interrupts along with four timers. The MPC107 uses an advanced, 2.5-volt HiP3 process technology and is fully compatible with TTL devices. Integrated Memory Controller The memory interface controls processor and PCI interactions to main memory. It supports a variety of programmable timing supporting DRAM (FPM, EDO), SDRAM, and ROM/Flash ROM configurations, up to speeds of 100 MHz. PCI Bus Support The MPC107 PCI interface is designed to connect the processor and memory buses to the PCI local bus without the need for "glue" logic at speeds up to 66 MHz. The MPC107 acts as either a master or slave device on the PCI MPC107 Block Diagram bus and contains a PCI bus arbitration unit 60x Bus which reduces the need for an equivalent Memory Data external unit thus reducing the total system Data Path ECC / Parity complexity and cost. -

The Impulse Memory Controller

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTERS, VOL. 50, NO. 11, NOVEMBER 2001 1 The Impulse Memory Controller John B. Carter, Member, IEEE, Zhen Fang, Student Member, IEEE, Wilson C. Hsieh, Sally A. McKee, Member, IEEE, and Lixin Zhang, Student Member, IEEE AbstractÐImpulse is a memory system architecture that adds an optional level of address indirection at the memory controller. Applications can use this level of indirection to remap their data structures in memory. As a result, they can control how their data is accessed and cached, which can improve cache and bus utilization. The Impuse design does not require any modification to processor, cache, or bus designs since all the functionality resides at the memory controller. As a result, Impulse can be adopted in conventional systems without major system changes. We describe the design of the Impulse architecture and how an Impulse memory system can be used in a variety of ways to improve the performance of memory-bound applications. Impulse can be used to dynamically create superpages cheaply, to dynamically recolor physical pages, to perform strided fetches, and to perform gathers and scatters through indirection vectors. Our performance results demonstrate the effectiveness of these optimizations in a variety of scenarios. Using Impulse can speed up a range of applications from 20 percent to over a factor of 5. Alternatively, Impulse can be used by the OS for dynamic superpage creation; the best policy for creating superpages using Impulse outperforms previously known superpage creation policies. Index TermsÐComputer architecture, memory systems. æ 1 INTRODUCTION INCE 1987, microprocessor performance has improved at memory. By giving applications control (mediated by the Sa rate of 55 percent per year; in contrast, DRAM latencies OS) over the use of shadow addresses, Impulse supports have improved by only 7 percent per year and DRAM application-specific optimizations that restructure data. -

Optimizing Thread Throughput for Multithreaded Workloads on Memory Constrained Cmps

Optimizing Thread Throughput for Multithreaded Workloads on Memory Constrained CMPs Major Bhadauria and Sally A. Mckee Computer Systems Lab Cornell University Ithaca, NY, USA [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION Multi-core designs have become the industry imperative, Power and thermal constraints have begun to limit the replacing our reliance on increasingly complicated micro- maximum operating frequency of high performance proces- architectural designs and VLSI improvements to deliver in- sors. The cubic increase in power from increases in fre- creased performance at lower power budgets. Performance quency and higher voltages required to attain those frequen- of these multi-core chips will be limited by the DRAM mem- cies has reached a plateau. By leveraging increasing die ory system: we demonstrate this by modeling a cycle-accurate space for more processing cores (creating chip multiproces- DDR2 memory controller with SPLASH-2 workloads. Sur- sors, or CMPs) and larger caches, designers hope that multi- prisingly, benchmarks that appear to scale well with the threaded programs can exploit shrinking transistor sizes to number of processors fail to do so when memory is accurately deliver equal or higher throughput as single-threaded, single- modeled. We frequently find that the most efficient config- core predecessors. The current software paradigm is based uration is not the one with the most threads. By choosing on the assumption that multi-threaded programs with little the most efficient number of threads for each benchmark, contention for shared data scale (nearly) linearly with the average energy delay efficiency improves by a factor of 3.39, number of processors, yielding power-efficient data through- and performance improves by 19.7%, on average. -

COSC 6385 Computer Architecture - Multi-Processors (IV) Simultaneous Multi-Threading and Multi-Core Processors Edgar Gabriel Spring 2011

COSC 6385 Computer Architecture - Multi-Processors (IV) Simultaneous multi-threading and multi-core processors Edgar Gabriel Spring 2011 Edgar Gabriel Moore’s Law • Long-term trend on the number of transistor per integrated circuit • Number of transistors double every ~18 month Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wki/Images:Moores_law.svg COSC 6385 – Computer Architecture Edgar Gabriel 1 What do we do with that many transistors? • Optimizing the execution of a single instruction stream through – Pipelining • Overlap the execution of multiple instructions • Example: all RISC architectures; Intel x86 underneath the hood – Out-of-order execution: • Allow instructions to overtake each other in accordance with code dependencies (RAW, WAW, WAR) • Example: all commercial processors (Intel, AMD, IBM, SUN) – Branch prediction and speculative execution: • Reduce the number of stall cycles due to unresolved branches • Example: (nearly) all commercial processors COSC 6385 – Computer Architecture Edgar Gabriel What do we do with that many transistors? (II) – Multi-issue processors: • Allow multiple instructions to start execution per clock cycle • Superscalar (Intel x86, AMD, …) vs. VLIW architectures – VLIW/EPIC architectures: • Allow compilers to indicate independent instructions per issue packet • Example: Intel Itanium series – Vector units: • Allow for the efficient expression and execution of vector operations • Example: SSE, SSE2, SSE3, SSE4 instructions COSC 6385 – Computer Architecture Edgar Gabriel 2 Limitations of optimizing a single instruction -

WP127: "Embedded System Design Considerations" V1.0 (03/06/2002)

White Paper: Virtex-II Series R WP127 (v1.0) March 6, 2002 Embedded System Design Considerations By: David Naylor Embedded systems see a steadily increasing bandwidth mismatch between raw processor MIPS and surrounding components. System performance is not solely dependent upon processor capability. While a processor with a higher MIPS specification can provide incremental system performance improvement, eventually the lagging surrounding components become a system performance bottleneck. This white paper examines some of the factors contributing to this. The analysis of bus and component performance leads to the conclusion that matching of processor and component performance provides a good cost-performance trade-off. © 2002 Xilinx, Inc. All rights reserved. All Xilinx trademarks, registered trademarks, patents, and disclaimers are as listed at http://www.xilinx.com/legal.htm. All other trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners. All specifications are subject to change without notice. WP127 (v1.0) March 6, 2002 www.xilinx.com 1 1-800-255-7778 R White Paper: Embedded System Design Considerations Introduction Today’s systems are composed of a hierarchy, or layers, of subsystems with varying access times. Figure 1 depicts a layered performance pyramid with slower system components in the wider, lower layers and faster components nearer the top. The upper six layers represent an embedded system. In descending order of speed, the layers in this pyramid are as follows: 1. CPU 2. Cache memory 3. Processor Local Bus (PLB) 4. Fast and small Static Random Access Memory (SRAM) subsystem 5. Slow and large Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) subsystem 6. -

Computer Architecture Lecture 12: Memory Interference and Quality of Service

Computer Architecture Lecture 12: Memory Interference and Quality of Service Prof. Onur Mutlu ETH Zürich Fall 2017 1 November 2017 Summary of Last Week’s Lectures n Control Dependence Handling q Problem q Six solutions n Branch Prediction n Trace Caches n Other Methods of Control Dependence Handling q Fine-Grained Multithreading q Predicated Execution q Multi-path Execution 2 Agenda for Today n Shared vs. private resources in multi-core systems n Memory interference and the QoS problem n Memory scheduling n Other approaches to mitigate and control memory interference 3 Quick Summary Papers n "Parallelism-Aware Batch Scheduling: Enhancing both Performance and Fairness of Shared DRAM Systems” n "The Blacklisting Memory Scheduler: Achieving High Performance and Fairness at Low Cost" n "Staged Memory Scheduling: Achieving High Performance and Scalability in Heterogeneous Systems” n "Parallel Application Memory Scheduling” n "Reducing Memory Interference in Multicore Systems via Application-Aware Memory Channel Partitioning" 4 Shared Resource Design for Multi-Core Systems 5 Memory System: A Shared Resource View Storage 6 Resource Sharing Concept n Idea: Instead of dedicating a hardware resource to a hardware context, allow multiple contexts to use it q Example resources: functional units, pipeline, caches, buses, memory n Why? + Resource sharing improves utilization/efficiency à throughput q When a resource is left idle by one thread, another thread can use it; no need to replicate shared data + Reduces communication latency q For example, -

Memory Controller SC White Paper

DEVELOPING HIGH-SPEED MEMORY INTERFACES: THE LatticeSCM FPGA ADVANTAGE A Lattice Semiconductor White Paper February 2006 Lattice Semiconductor 5555 Northeast Moore Ct. Hillsboro, Oregon 97124 USA Telephone: (503) 268-8000 www.latticesemi.com Developing High-Speed Memory Interfaces A Lattice Semiconductor White Paper Introduction A common problem for today’s system designers is to reliably interface to their next generation high- speed memory devices. As system bandwidths continue to increase, memory technologies have been optimized for higher speeds and performance. As a result, these next generation memory interfaces are also increasingly challenging to design to. Implementing high-speed, high-efficiency memory interfaces in programmable logic devices such as FPGAs has always been a major challenge for designers. Lattice Semiconductor offers customers a high performance FPGA platform in the LatticeSC to design high-speed memory interface solutions. The LatticeSC family implements various features on- chip that facilitate designing high-speed memory controllers to interface to the next generation high- speed, high performance DDR SDRAM, QDR SRAM, and emerging RLDRAM memory devices. The PURESPEED I/O structures on the LatticeSC, combined with the clock management resources and a high-speed FPGA fabric help customers reduce design risk and time-to-market for high-speed memory based designs. Additionally, the LatticeSCM family implements full-featured embedded high-speed memory controllers on-chip to interface smoothly to the next generation high-speed, high performance DDR I/II SDRAM, QDR II SRAM, and RLDRAM I/II memory devices. The embedded memory controllers, coupled with the I/O structures and clock management resources, are fully verified controllers for customers to use as off-the-shelf solutions. -

Intel Xeon Scalable Family Balanced Memory Configurations

Front cover Intel Xeon Scalable Family Balanced Memory Configurations Last Update: 20 November 2017 Demonstrates three balanced Compares the performance of memory guidelines for Intel Xeon balanced and unbalanced memory Scalable processors configurations Explains memory interleaving and Provides tips on how to balance its importance memory and maximize performance Dan Colglazier Joseph Jakubowski Jamal Ayoubi Abstract Configuring a server with balanced memory is important for maximizing its memory bandwidth and overall performance. Lenovo® ThinkSystem™ servers running Intel Xeon Scalable Family processors have six memory channels per processor and up to two DIMMs per channel, so it is important to understand what is considered a balanced configuration and what is not. This paper defines three balanced memory guidelines that will guide you to select a balanced memory configuration. Balanced and unbalanced memory configurations are presented along with their relative measured memory bandwidths to show the effect of unbalanced memory. Suggestions are also provided on how to produce balanced memory configurations. This paper is for ThinkSystem customers and for business partners and sellers wishing to understand how to maximize the performance of Lenovo servers. At Lenovo Press, we bring together experts to produce technical publications around topics of importance to you, providing information and best practices for using Lenovo products and solutions to solve IT challenges. See a list of our most recent publications at the Lenovo Press web site: http://lenovopress.com Do you have the latest version? We update our papers from time to time, so check whether you have the latest version of this document by clicking the Check for Updates button on the front page of the PDF. -

10Th Gen Intel® Core™ Processor Families Datasheet, Vol. 1

10th Generation Intel® Core™ Processor Families Datasheet, Volume 1 of 2 Supporting 10th Generation Intel® Core™ Processor Families, Intel® Pentium® Processors, Intel® Celeron® Processors for U/Y Platforms, formerly known as Ice Lake July 2020 Revision 005 Document Number: 341077-005 Legal Lines and Disclaimers You may not use or facilitate the use of this document in connection with any infringement or other legal analysis concerning Intel products described herein. You agree to grant Intel a non-exclusive, royalty-free license to any patent claim thereafter drafted which includes subject matter disclosed herein. No license (express or implied, by estoppel or otherwise) to any intellectual property rights is granted by this document. Intel technologies' features and benefits depend on system configuration and may require enabled hardware, software or service activation. Performance varies depending on system configuration. No computer system can be absolutely secure. Check with your system manufacturer or retailer or learn more at intel.com. Intel technologies may require enabled hardware, specific software, or services activation. Check with your system manufacturer or retailer. The products described may contain design defects or errors known as errata which may cause the product to deviate from published specifications. Current characterized errata are available on request. Intel disclaims all express and implied warranties, including without limitation, the implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and non-infringement, as well as any warranty arising from course of performance, course of dealing, or usage in trade. All information provided here is subject to change without notice. Contact your Intel representative to obtain the latest Intel product specifications and roadmaps Copies of documents which have an order number and are referenced in this document may be obtained by calling 1-800-548- 4725 or visit www.intel.com/design/literature.htm.