Benjamin Fondane Was a Poet, a Literary Critic, and a Disciple of the Philosopher Lev Shestov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Download Programme PDF Format

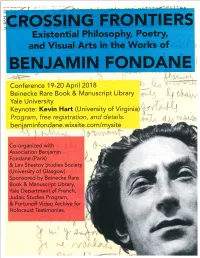

CROSSING FRONTIERS EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY, POETRY, AND VISUAL ARTS IN THE WORKS OF BENJAMIN FONDANE BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY YALE UNIVERSITY APRIL 19-20, 2018 Keynote Speaker: Prof. Kevin Hart, Edwin B. Kyle Professor of Christian Studies, University of Virginia Organizing Committee: Michel Carassou, Thomas Connolly, Julia Elsky, Ramona Fotiade, Olivier Salazar-Ferrer Administration: Ann Manov, Graduate Student & Webmaster Agnes Bolton, Administrative Coordinator “Crossing Frontiers” has been made possible by generous donations from the following donors: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, Yale University Judaic Studies Program, Yale University Department of French, Yale University The conference has been organized in conjunction with the Association Benjamin Fondane (Paris) and the Lev Shestov Studies Society (University of Glasgow) https://benjaminfondane.wixsite.com/mysite THURSDAY, APRIL 19 Coffee 10.30-11:00 Panel 1: Philosophy and Poetry I 11.00-12.30 Room B 38-39 Chair: Alice Kaplan (Yale University) Bruce Baugh (Thompson Rivers University), “Benjamin Fondane: From Poetry to a Philosophy of Becoming” Olivier Salazar-Ferrer (University of Glasgow), “Revolt and Finitude in the Representation of Odyssey” Michel Carassou (Association Benjamin Fondane), “De Charlot à Isaac Laquedem. Figures de l’émigrant dans l’œuvre de Benjamin Fondane” [in French] Lunch in New Haven 12.30-14.30 Panel 2: Philosophy and Poetry II 14.30-16.00 Room B 38-39 Chair: Maurice Samuels (Yale University) Alexander Dickow (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University), “Rhetorical Impurity in Benjamin Fondane’s Poetic and Philosophical Works” Cosana Eram (University of the Pacific), “Consciousness in the Abyss: Benjamin Fondane and the Modern World” Chantal Ringuet (Brandeis University), “A World Upside Down: Marc Chagall’s Yiddish Paradise According to Benjamin Fondane” Keynote 16.15 Prof. -

Hypothesis on Tararira, Benjamin Fondane's Lost Film

www.unatc.ro Academic Journal of National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale” – Vol. 2, No. 1, 2018 UNATC PRESS UNATC The academic journal of the National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale“ publishes original papers aimed to analyzing in-depth different aspects of cinema, film, television and new media, written in English. You can find information about the way to submit papers on cover no 3 and at the Internet address: www.unatc.ro Editor in chief: Dana Duma Deputy editor: Andrei Gorzo [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Managing Editor: Anca Ioniţă [email protected] Copy Editor: Andrei Gorzo, Anca Ioniță Editorial Board: Laurenţiu Damian, Dana Duma, Andrei Gorzo, Ovidiu Georgescu, Marius Nedelcu, Radu Nicoară Advisory Board: Dominique Nasta (Université Libre de Bruxelles) Christina Stojanova (Regina University, Canada) Tereza Barta (York University, Toronto, Canada) UNATC PRESS ISSN: 2343 – 7286 ISSN-L: 2286 – 4466 Art Director: Alexandru Oriean Photo cover: Vlad Ivanov in Dogs by Bogdan Mirică Printing House: Net Print This issue is published with the support of The Romanian Filmmakers’ Union (UCIN) National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale” Close Up: Film and Media Studies Vol. 2, No. 1, 2018 UNATC PRESS BUCUREȘTI CONTENTS Close Up: Film and Media Studies • Vol. 2, No. 1, 2018 Christina Stojanova Some Notes on the Phenomenology of Evil in New Romanian Cinema 7 Dana Duma Hypothesis on Tararira, Benjamin Fondane’s Lost Film 19 Andrei Gorzo Making Sense of the New Romanian Cinema: Three Perspectives 27 Ana Agopian For a New Novel. -

Dialog 20.Indd

GÈNEVIÈVE FONDANE O viaţă închinată misterului lui Israel P. Michel CAGIN Abbaye Saint-Pierre din Solesmes, Franţa „… Trebuie să fi fost Israel sau să se fi dedicat cu o iubire specială Israelului, pentru a-i pătrunde imensitatea, atât misterul, cât și sfâșierea”. Gèneviève Fondane către Jacques Maritain, 19 octombrie 1945 Nu se va căuta în aceste pagini nimic nou1. Doar scrisoarea pe care o vom publica la sfârșitul lor este inedită. Am încercat doar să trasăm din nou adevă- rul, puritatea și densitatea mărturiei pe care Gèneviève a lăsat-o despre voca- ţia sa și despre itinerarul său, pe parcursul scrisorilor către prietenii săi (în special către Jacques și Raissa Maritain) și câteva note intime.2 Această schiţă nu are altă ambiţie decât de a dori să facă cunoscută această mărturie discretă și captivantă, știind bine că ea se va îndrepta fără zgomot către cei care vor ști să o recunoască și să o înţeleagă. * 1 Articolul a fost preluat din revista Nova et Vetera (Geneva), numărul din ianuarie-iunie 2003, 102-122. Titlul original al articolului: „Gèneviève Fondaine, une vie vouée au mystère d’Israël”. Părintele Michel Cagin, OSB, s-a născut în 1954; a studiat Literatura modernă la École Normale Supérieure din Paris; este călugăr la Solesmes, unde predă teologia. 2 Pasajele citate aici sunt în mare parte extrase din cartea Fondane-Maritain, corespon- denţa dintre Benjamin și Geneviève Fondane cu Jacques și Raissa Maritain, editată de Michel Carassou și René Mougel la Editura „Paris-Mediteranee”, 1997, 216 pag. Câteva scrisori la alţi corespondenţi au apărut în Buletinul Societăţii de Studii Benjamin Fondane, publicat în Israel. -

Deschide Cartea

1 2 de colecție Nr. 4 3 4 Benjamin Fundoianu Herța și alte priveliști P OEME ALESE DE D an Coman Fotografii de Vitalie Coroban 5 6 Despre autor Benjamin Fundoianu (pseud. lui Benjamin Wexler), 14 noiembrie 1898, Iași – 2 octombrie 1944, Auschwitz (Polo- nia), poet și eseist, luîndu-și numele literar de la moșia Fun- doaia (jud. Dorohoi), unde bunicul dinspre tată fusese arendaș. Studii la Liceul Național și la Facultatea de Drept a Universității din Iași. Debutul poetic în revista Valuri, Iași, 1914. Debutul editorial are loc în 1918, cu o povestire de inspirație biblică, Tăgăduința lui Petru. Colaborează cu po- eme și foiletoane pe teme diverse la Viața nouă, Rampa, Adevărul literar și artistic, Contimporanul, Integral etc. O parte din eseuri vor fi adunate în volumul Imagini și cărți din Franța (1922). Împreună cu regizorul Armand Pascal întemeiază teatrul de avangardă Insula, pe care, din lipsă de mijloace materiale, sunt nevoiți să-l desființeze în 1923, anul în care Fundoianu se și expatriază. De la Paris, cu ajutorul prietenilor din țară și al lui Ion Minulescu în mod deosebit, face să apară volumul Priveliști (1930). 7 În decembrie 1923, emigrează în Franţa, unde, cîteva luni mai tîrziu, îl va întîlni pe Lev Şestov, filosoful de origine rusă a cărui gîndire îl va marca pentru totdeauna. În 1931, se căsătoreşte cu Geneviève Tissier (1904-1954), iar în 1938 obține cetățenia franceză. Este o perioadă de intensă creativitate, în care autorul, devenit Benjamin Fondane, îşi concepe opera în limba franceză, doar parţial publicată în timpul vieţii. După o perioadă de privațiuni, publică în prestigioase re- viste de profil din Franța, iar, mai tîrziu, și în reviste de peste Ocean, continuînd să trimită colaborări la revistele din țară. -

Romanian Literature for the World: a Matter of Property

World Literature Studies 2 . vol. 7 . 2015 (3–14) ŠTÚDIE / ARTIclEs Romanian literature for the world: a matter of property AndRei TeRiAn For many Romanian intellectuals of the 19th–20th centuries, the relation of their national literature to world literature(s) was not only a pressing question to consider, but also a real obsession which has led to two extreme attitudes in modern Romanian intellectual culture. On the one hand, a number of Romanian writers and scholars (some of whom deliberately left for the West) have described the situation of their own culture from a pamphlet and/or self-victimizing position, which confirmed a foreign researcher’s observation that “self-denigration is an essential component of the Romanian self-image and is deeply rooted in the matrix of the national culture” (Deletant 2007, 224). On the other hand, the inferiority complexes of Romanian lit- erature in relation to world literature have been translated, starting from the middle of the 19th century, by attempts to euphemize, exorcize, sublimate and even attempt their imaginary conversion into superiority complexes (see Goldiş 2014). ROMANIAN LITERATURE AND THE WORLD Despite this radical antinomy present in Romanian cultural discourse, we can still note that most of the time its representatives agreed on three matters for discussion that call for a more careful analysis. The first aspect relates to the concept of Romanian literature as such. With the exception of the protochronists,1 in Romanian literary historians’ opinion, Roma- nian literature was -

ASTRA SALVENSIS -Revistã De Istorie Şi Culturã

ASTRA SALVENSIS -Revistã de istorie şi culturã- YEAR V NUMBER 9 Salva 2017 Proceedings of the International Conference Education, Religion, Family in Contemporary Society, 1st Edition, Beclean, 10-11th of November, 2016, Romania Astra Salvensis - review of history and culture, year V, No. 9, 2017 Review edited by ASTRA EDITORIAL BOARD: Nãsãud Department, Salva Circle and ,,Vasile Moga” Department from Sebeş Mihai-Octavian Groza (Cluj- Napoca), Iuliu-Marius Morariu Director: Ana Filip (Cluj-Napoca), Diana-Maria Dãian (Cluj-Napoca), Andrei Deputy director: Iuliu-Marius Morariu Pãvãlean (Cluj-Napoca), Adrian Editor-in-chief: Mihai-Octavian Groza Iuşan (Cluj-Napoca), Grigore- Toma Someşan (Cluj-Napoca), FOUNDERS: Andrei Faur (Cluj-Napoca), Ioan Seni, Ana Filip, Romana Fetti, Vasilica Augusta Gãzdac, Gabriela-Margareta Nisipeanu Luminia Cuceu, Iuliu-Marius Morariu (Cluj-Napoca), Daria Otto (Wien), Petro Darmoris (Liov), Flavius Cristian Mãrcãu (Târgu- SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE: Jiu), Olha Soroka (Liov), Tijana Petkovic (Belgrade), Robert PhD. Lecturer Daniel Aron Alic, ,,Eftimie Murgu" University, Reşia; Mieczkokwski (Warsaw), PhD. Emil Arbonie, ,,Vasile Goldiş” University, Arad; Melissa Trull (Seattle) PhD. Assist. Prof. Ludmila Bãlat, ,,B. P. Haşdeu” University, Cahul; PhD. Lecturer Maria Barbã, ,,B. P. Ha deu University, Cahul; ş ” PhD. Assoc. Prof. Alex Bãlaş, New York State University from Cortland; PhD. Assoc. Prof. Ioan Cârja, ,,Babeş-Bolyai” University, Cluj-Napoca; Translation of abstracts: PhD. Luminia Cornea, Independent Researcher, Sfântu Gheorghe; Melissa Trull Phd. Lecturer Mihai Croitor, ,,Babeş-Bolyai” University, Cluj-Napoca; Iuliu-Marius Morariu PhD. Prof. Theodor Damian, The Romanian Institute of Orthodox Theology and Anca-Ioana Rus Spirituality/Metropolitan College, New York; Covers: PhD. Dorin Dologa, National Archives of Romania, Bistri a-Nãsãud Districtual Service; PhD. -

RUMANIAN AVANT-GARDE 1916 – 1947 Books, Collage, Drawings, Graphic Design, Paintings, Periodicals, Photography, Posters

RUMANIAN AVANT-GARDE 1916 – 1947 Books, Collage, Drawings, Graphic Design, Paintings, Periodicals, Photography, Posters October 24 – December 5, 1998 In Association with Michael Ilk and Antiquariaat J.A. Vloemans, The Hague “Brancusi, Tzara und die Rumänsche Avantgarde,” an illustrated, softcover catalogue (127 pages) by Michael Ilk is available. A numbered, hardbound edition of 50 examples each containing a lithograph by S. Perahim (1997) is also available. FRONT ROOM East Wall 1. Attributed to Tristan Tzara Untitled (maquette for the cover of “The Little Review,” Autumn/Winter 1923 – 1924) 1923 Halftone cut-outs and gouache on board 9 1/2” x 7 1/2” (framed) Accompanied by an example of “The Little Review,” Quarterly Journal of Arts & Letters, New York, Autumn/Winter 1923 – 1924 Marc Dachy, the noted Dada scholar, has made the attribution of this work to Tzara. See text on page 128 of “Poesure et Peintrie,” Musée de Marselle, 1993. The work was included in this exhibition and is reproduced on page 118. 2. Marcel Janco “Don Quixote” (drawing for “Exercitii pentru mana dreapta si Don Quichotte” by Jacques Costin) 1931 India ink and pencil on paper 10 1/8” x 7 3/4” (Ilk – page 93, K96) 3. Marcel Janco “Ire Exposition Dada” 1917 Lithograph on paper (backed) 16 5/8” x 10 1/4” (Ilk – page 100, K100) Poster for the first Dada exhibition, which was held at the Galerie Corray UBU GALLERY 416 EAST 59 STREET NEW YORK NY 10022 TEL: 212 753 4444 FAX: 212 753 4470 [email protected] WWW.UBUGALLERY.COM Rumanian Avant-Garde, 1916 – 1947 October 24 – December 5, 1998 Page 2 of 15 North Wall 4. -

A Scenery – B. Fondane's Stages of Creation

DISCOURSE AS A FORM OF MULTICULTURALISM IN LITERATURE AND COMMUNICATION SECTION: HISTORY AND CULTURAL MENTALITIES ARHIPELAG XXI PRESS, TÎRGU MUREȘ, 2015, ISBN: 978-606-8624-21-1 A SCENERY – B. FONDANE’S STAGES OF CREATION Sorin Suciu Assist. Prof., PhD, ”Sapientia” University of Tîrgu Mureș Abstract: Our paper tries to mark Benjamin Wechslerřs way into the world, as he became B. Fundoianu, the poet, and ended as B. Fondane, the philosopher and poet, exploring the inside of one of the Naziřs crematories, carrying all the way to the end the legacy of his mentor, Leo Chestov. We are trying to sketch a scenery of Fondaneřs stages of creation by refreshing the most relevant criticism on the poetřs work, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, by enlightening the reasons which made Fondane to quit on poetry, for a long period of time, and even to quit on Romanian language. Keywords: poetry, criticism, language, destiny, fracture. Vom porni la drum pe urmele evreului rătăcitor, „leprosul‖ ce nu-şi găsea locul nici printre străini, dar nici printre ai săi. Născut în 1898, Benjamin Wechsler a fost fiul mijlociu al unui agent de asigurare din ţinutul Herţei, Isac, şi al Adelei, născută Schwartzfeld, fiica lui Benjamin Schwartzfeld, venit din Galiţia şi fondator al primei şcoli evreieşti din Iaşi. Pe Tânărul poet este fermecat de ţinutul în care s-a născut dar, pe de altă parte, este rupt între tradiţia evreiască insuflată de către bunic şi trăirile sale interioare potenţate de condiţia aleasă de „lepros‖, unul atins, totuși, de orgoliul luciferic, -

Reseña De" Francophonie Et Multiculturalisme Dans Les Balkans

Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Sistema de Información Científica Estrella de la Torre Giménez Reseña de "Francophonie et multiculturalisme dans les Balkans" de Efstratia Oktapoda Lu (dir.) Francofonía, núm. 15, 2006, pp. 277-279, Universidad de Cádiz España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=29501526 Francofonía, ISSN (Version imprimée): 1132-3310 [email protected] Universidad de Cádiz España ¿Comment citer? Compléter l'article Plus d'informations de cet article Site Web du journal www.redalyc.org Le Projet Académique à but non lucratif, développé sous l'Acces Initiative Ouverte Francofonía 15.qxd 4/10/06 13:40 Página 276 Comptes rendus Comptes rendus diation par un mari imbu de sa personne qui contrôle toute sa vie: “Ma dans leurs rapports. Pour sortir de l’enfer dans lequel la honte a jeté la mère n’était pas censée posséder de l’argent, elle n’allait pas chez le coif- famille, nulle autre solution que celle de la marier malgré elle à un fils feur ni au hammam, et encore moins aux mariages, mon père lui inter- d’un notable de la ville ne lui paraît possible. Pour ses parents le jeune disait tout” (35-36). prétendant qui souffre d’une tare rédhibitoire a sauvé leur honneur en L’adolescente accepte difficilement l’état de soumission de sa mère acceptant d’épouser celle qui est désormais considérée aux yeux de tous et vit avec un certain détachement cette réalité aliénante et étouffante. comme une traînée. Mais entre la mère et la fille une grande déchirure Mais le jour où son père la surprend dans un parc, nue, s’offrant à un s’installe et leur relation se détériore totalement. -

STUDII EMINESCOLOGICE Vol. 3

STUDII EMINESCOLOGICE 3 Volumul Studii Eminescologice este publicaţia anuală a Bibliotecii Judeţene „Mihai Eminescu” Botoşani. Apare în colaborare cu Catedra de Literatură Comparată şi Teoria Literaturii / Estetică a Universităţii „Al. I. Cuza” din Iaşi ISBN 973–555–315–5 STUDII EMINESCOLOGICE 3 Coordonatori: Ioan CONSTANTINESCU Cornelia VIZITEU CLUSIUM 2001 Lector: Corina Mărgineanu Coperta: Lucian Andrei Culegere & Tehnoredactare: Marius GLASBERG, Iulian MOLDOVAN Corectura a fost asigurată de către Biblioteca Judeţeană „Mihai Eminescu” Botoşani Cuvânt înainte Bilanţul „Anului Eminescu” Cornelia VIZITEU Probabil că pentru destui cititori, în mod cert, pentru unii specialişti, încheierea anului Eminescu a putut însemna ceva important. Cât oare de important? Şi oare cât timp au avut ei să consacre festivalurilor, simpozioanelor, spectacolelor ce au avut loc, articolelor, cuvântărilor, cărţilor dedicate celor 150 de ani de la naşterea marelui poet? Dar bibliotecarii? Le adresăm şi lor aceleaşi întrebări şi o facem cu toată deferenţa pe care ştim că o merită şi chiar cu toată dragostea noastră… nelivrescă; pentru că ei au fost cei care au dus greul îndelungului An Eminescu şi au respirat praful vechi al cărţilor de acum 60, 80, 100 sau chiar peste 130 de ani (întrucât poezii ale sale, cum ne spune eruditul german Klaus Heitmann, au fost traduse încă în 1878), ca şi praful nou ce se depune şi pe cele mai noi cărţi eminesco- logice. Noi, bibliotecarii, am fost, probabil, cei mai interesaţi să surprindem, să înregistrăm, să catalogăm, pe de o parte totul, pe de alta – noutatea, cartea de excepţie sau măcar cea care atrage atenţia printr-o interpretare diferită de cele de 5 până acum a unei opere sau a alteia. -

Revista „Vitraliu", Editată La Centrul De Cultură George Apostu Din Bacău

PERIODIC AL CENTRULUI CULTURAL INTERNAŢIONAL ,GEORGE APOSTU"- BACAU ANUL XVIII, NR. 1-2 (34) APRILIE 2010 LEI3,50 e e "Ce caută aceste elemente nesănătoase în viaţa publică a statului? Ce caută aceşti oameni cari pe calea statului voiesc să câştige avere şi onori, pe când statul nu este nicăieri altceva decât organizarea cea mai simplă a nevoilor omeneşti? Ce sunt aceste păpuşi cari doresc a trăi fără muncă, fără ştiinţă, fără avere moştenită._.?" Mihai EMINESCU, Icoane vechi şi icoane nouă (decembrie 1877) www.cimec.ro ;... ..... ,/'..{ ..:...,; �. � .--.__...: � -_.,_ _...... � ,. ·-r, � ... f"""-t-r� � l:'X /fe.lit; � Doina Mihai EMINESCU ne la Nistru pân'1a Tisa Tot Românul plânsu-mi:S-a €ă nu mai poate străbate De-atâta străinătate. Din Hotin şi pân' la Mare Vin Muscalii de-a călare, De la Mare la Hotin 1 Mereu calea ne-o aţin; ' Din Boiau la Vatra-Dornii Atrumplut omida cornii Şi străinul ne tot paşte .. p � ·� De nu te mai poţi cunoaşte; . ........__ ..� Sus la munte, jos pe vale, .... Şi-au făcut duşmanii cale, r Din Sătrnar pân 'în Săcele ...., • tit-.. Numai vaduri ca ace\e . ·--*+ �- .. � -J<.c Vai de biet Român săracul, �t. / Îndărăt tot dă ca racul, Nici îi merge, nici se-ndeamnă, ...... Niciîi este toamna toamnă, ici e vară vara lui Şi-i străinîn ţara lui. ... De la Turnu-n Dorohoi Curg duşmanii în puhoi Şi s-aşează pe la noi; 1 Şi cum vin cu drum de fier, Toate cântecele pier, Sboară păsările toate De neagra străinătate; Numai umbra spinului � La uşa creştinului. "' Îşi desbracă-ţara sânul, Codrul - frate cu Românul De săcure se tot pleacă Şi izvoarele îi.seacă - Sărac în ţară săracă! Cine-auîndrăgit străînii Mânca-i-ar inima cânii, Mânca-i-ar casa pustia Şi neamul nemernicia! '- Ştefane, Măria Ta, Tu la Putna nu mai sta, Las' Archimandritului Toată grija schitului, La�ă grija Sfinţilor În sama părinţilor, 1 Clopotele să le tragă .......• t.