Romanian Literature for the World: a Matter of Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Woods and Water to the Gran Bazaar: Images of Romania in English Travelogues After Wwi

LINGUACULTURE 2, 2015 FROM WOODS AND WATER TO THE GRAN BAZAAR: IMAGES OF ROMANIA IN ENGLISH TRAVELOGUES AFTER WWI ANDI SÂSÂIAC Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi, Romania Abstract Although globalization brings different countries and cultures in closer and closer contact, people are still sensitive when it comes to aspects such as cultural specificity or ethnicity. The collapse of communism and the extension of the European Union have determined an increase of interest in Romania’s image, both on the part of foreigners and of Romanians themselves. The purpose of this paper is to follow the development of Romania’s image in English travelogues in the last hundred years, its evolution from a land of “woods and water” in the pre-communist era to a “grand bazaar” in the post- communist one, with clear attempts, in recent years, to re-discover a more idyllic picture of the country, one that should encourage ecological tourism. The article is also intended to illustrate the extra-textual (historical, economic, cultural) factors that have impacted, in different ways, on this image evolution. Key words: image, cliché, stereotype, travel writing, travelogue, history, power relations Introduction According to Latham jr. (25), immediately after WWI, Romania remained a subject of interest to the English-speaking world because of its war debts and because it was a member of the Little Entente (also comprising Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia). Both the cultural and political life of Romania and its relations with the Western countries took a rather paradoxical turn after the accomplishment of the long standing ideal of Romanian unity in 1918. -

The Discourse on Humour in the Romanian Press Between 1948-1965

SLOVO, VOL. 31, NO. 2 (SUMMER 2018), 17-47 DOI: 10.14324/111.0954-6839.081 The Discourse on Humour in the Romanian Press between 1948-1965 EUGEN CONSTANTIN IGNAT University of Bucharest INTRODUCTION Once the official proclamation of the Romanian People’s Republic takes place, on the 30th of December 1947, the process of imposing new cultural values on society gradually permeates all areas of Romanian social life. Humour also becomes part of this process of transforming the social and cultural life, often regarded as a powerful weapon with which to attack ‘old’ bourgeois mentalities. According to Hans Speier, the official type of humour promoted by an authoritarian regime is political humour, which contributes to maintain the existent social order, or plays its part in changing it – all depending on those holding the reins over mass- media.1 Taking the Soviet Union as a model, the Romanian new regime imposes an official kind of humour, created through mass-media: the press, the radio, literature, cinematography, and television. This paper analyses the Romanian discourse on humour, reflected in the press, between 1948-1965,2 in cultural magazines3 such as Contemporanul (1948-1965), Probleme de 1 Hans Speier, ‘Wit and politics. An essay on laughter and power,’ American Journal of Sociology, 103 (1998), p.1353. 2 This period represents the first phase in the history of the communist regime in Romania. After a transitional period (1944-1947), the year 1948 marks the establishment of the communist regime in Romania. Through a series of political, economic, social, and cultural measures, such as the adoption of a new Constitution, banning of opposition parties, nationalization of the means of production, radical transformation of the education system or ‘Sovietisation’ of culture, the new regime radically transforms Romanian society. -

Zamfir BĂLAN, 2018, Fals Jurnal De Călătorie: Spovedanie Pentru

Fals jurnal de călătorie: Spovedanie pentru învinși de Panait Istrati1 Zamfir BĂLAN⁎ „O flacără, după alte mii, tocmai s-a stins, pe un întins teritoriu, plin de speranțe” (Panait Istrati, Spovedanie pentru învinși) Keywords: Panait Istrati; Nikos Kazantzakis; diary; journey; Bolshevism În 1929, după o lungă și tumultuoasă călătorie în URSS, Panait Istrati își mărturisea cu amărăciune, resemnat, dezamăgirea, în cartea Spovedanie pentru învinși. Visul se risipise. Vălul căzuse și realitatea își arătase adevăratul chip, cu atât mai hidos, cu cât speranțele fuseseră mai înflăcărate. Aproape toată lumea cunoaște astăzi povestea: invitat la aniversarea a zece ani de la revoluția bolșevică, Panait Istrati pornise spre Moscova, în toamna anului 1927, cu așteptări atât de mari – iar propaganda sovietică știuse să i le facă să pară atât de îndreptățite și de veridice – încât nu i s-a părut cu nimic exagerat să anunțe că s-a hotărât să devină cetățean al URSS După aproape doi ani de la aceste declarații înflăcărate, ieșea de sub tipar, sub semnătura sa, o carte care avea să scuture din temelii imaginea creată de propaganda sovietică lumii noi de la răsărit – Spovedanie pentru învinși. După șaisprezece luni în URSS. Istrati se declara învins și recunoștea astfel că tot ceea ce susținuse în legătură cu „modelul de umanitate” înălțat peste ruinele Rusiei țariste fusese o iluzie ca multe altele. Cum s-a ajuns aici? Unde se înșelase Panait Istrati? Declarațiile sale de adeziune fuseseră expresia unei credințe profunde sau numai efectul unor influențe bine instrumentate? Se amăgise „Gorki al Balcanilor”, cuprins de „mirajul bolșevismului”? Care fusese drumul său de la implicarea în disputele sindicale, de la grevele din portul Brăila, până la admirația pentru Lenin, liderul care găsea în „reprimarea fără milă” izvorul puterii bolșevice? Să fi fost Panait Istrati victima unei imense confuzii între ideologia social- democrației și platforma teoretică a revoluției bolșevice? N-ar fi fost singurul ademenit de „lupta” pentru dreptate, pentru o lume lipsită de exploatare. -

Romanian Literature Intoday'sworld

Journal of World Literature 3 (2018) 1–9 brill.com/jwl Romanian Literature in Today’s World Introduction Delia Ungureanu University of Bucharest and Harvard University [email protected] Thomas Pavel University of Chicago [email protected] What remains of a literature written and published for nearly half a century under a dictatorial regime? Will it turn out to be just a “‘parenthesis’ in history, meaningless in the future and unintelligible to anyone who did not live it”? So asks a major Romanian comparatist who chose exile in 1973, Matei Călinescu, quoting literary critic Alexandru George’s open letter to another preeminent figure of Romanian exile, Norman Manea. “What will last, indeed, of so many works written precisely to last, to bypass the misery and shame of an immediate nightmarish history?” (247). And how will this totalitarian legacy affect the present-day literature and its circulation and reception on the international market today? Călinescu concludes his 1991 article by placing his bet on “the young gener- ation of Romanians, less affected by the Ceaușescu legacy than their parents,” a generation that is “spontaneously inclined toward Europe, democracy and pluralism,” and includes “the young writers who call themselves ‘postmodern.’” (248). Quoting The Levant, a major epic in verse by Mircea Cărtărescu, the lead- ing figure of this generation, Călinescu trusts that “It is on such trends—which might well coalesce into a major new style equaling in importance the phe- nomenon of magical realism of the last forty years or so—that one could base one’s fondest hopes for the cultural future of Romania and of the newly liber- ated Eastern Europe as a whole” (248). -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Romania Redivivus

alexander clapp ROMANIA REDIVIVUS nce the badlands of neoliberal Europe, Romania has become its bustling frontier. A post-communist mafia state that was cast to the bottom of the European heap by opinion- makers sixteen years ago is now billed as the success story Oof eu expansion.1 Its growth rate at nearly 6 per cent is the highest on the continent, albeit boosted by fiscal largesse.2 In Bucharest more politicians have been put in jail for corruption over the past decade than have been convicted in the rest of Eastern Europe put together. Romania causes Brussels and Berlin almost none of the headaches inflicted by the Visegrád Group—Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia— which in 1993 declined to accept Romania as a peer and collectively entered the European Union three years before it. Romanians con- sistently rank among the most Europhile people in the Union.3 An anti-eu party has never appeared on a Romanian ballot, much less in the parliament. Scattered political appeals to unsavoury interwar traditions—Legionnairism, Greater Romanianism—attract fewer voters than do far-right movements across most of Western Europe. The two million Magyars of Transylvania, one of Europe’s largest minorities, have become a model for inter-ethnic relations after a time when the park benches of Cluj were gilded in the Romanian tricolore to remind every- one where they were. Indeed, perhaps the aptest symbol of Romania’s place in Europe today is the man who sits in the Presidential Palace of Cotroceni in Bucharest. Klaus Iohannis—a former physics teacher at a high school in Sibiu, once Hermannstadt—is an ethnic German head- ing a state that, a generation ago, was shipping hundreds of thousands of its ‘Saxons’ ‘back’ to Bonn at 4,000–10,000 Deutschmarks a head. -

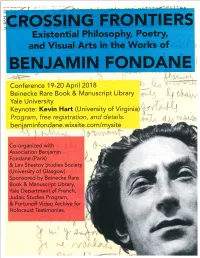

Download Programme PDF Format

CROSSING FRONTIERS EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY, POETRY, AND VISUAL ARTS IN THE WORKS OF BENJAMIN FONDANE BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY YALE UNIVERSITY APRIL 19-20, 2018 Keynote Speaker: Prof. Kevin Hart, Edwin B. Kyle Professor of Christian Studies, University of Virginia Organizing Committee: Michel Carassou, Thomas Connolly, Julia Elsky, Ramona Fotiade, Olivier Salazar-Ferrer Administration: Ann Manov, Graduate Student & Webmaster Agnes Bolton, Administrative Coordinator “Crossing Frontiers” has been made possible by generous donations from the following donors: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, Yale University Judaic Studies Program, Yale University Department of French, Yale University The conference has been organized in conjunction with the Association Benjamin Fondane (Paris) and the Lev Shestov Studies Society (University of Glasgow) https://benjaminfondane.wixsite.com/mysite THURSDAY, APRIL 19 Coffee 10.30-11:00 Panel 1: Philosophy and Poetry I 11.00-12.30 Room B 38-39 Chair: Alice Kaplan (Yale University) Bruce Baugh (Thompson Rivers University), “Benjamin Fondane: From Poetry to a Philosophy of Becoming” Olivier Salazar-Ferrer (University of Glasgow), “Revolt and Finitude in the Representation of Odyssey” Michel Carassou (Association Benjamin Fondane), “De Charlot à Isaac Laquedem. Figures de l’émigrant dans l’œuvre de Benjamin Fondane” [in French] Lunch in New Haven 12.30-14.30 Panel 2: Philosophy and Poetry II 14.30-16.00 Room B 38-39 Chair: Maurice Samuels (Yale University) Alexander Dickow (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University), “Rhetorical Impurity in Benjamin Fondane’s Poetic and Philosophical Works” Cosana Eram (University of the Pacific), “Consciousness in the Abyss: Benjamin Fondane and the Modern World” Chantal Ringuet (Brandeis University), “A World Upside Down: Marc Chagall’s Yiddish Paradise According to Benjamin Fondane” Keynote 16.15 Prof. -

Patterns of Violence in Greek and Romanian Rural Settings

JOURNAL OF ROMANIAN LITERARY STUDIES Issue no. 10/2017 PATTERNS OF VIOLENCE IN GREEK AND ROMANIAN RURAL SETTINGS Catalina Elena Prisacaru KU LEUVEN Research Assistant Intern Abstract: The following paper brings a contribution to researches carried out in the field of anthropology and social sciences on the issues of rural violence. The study focuses on the collective memory and imagery documents recorded and depicted in literature, seeking to uncover patterns of rural violence, taking as a case study two novellas representative for Greek and Romanian rural settings. The findings note the affinities and shared patterns between these two cultural settings and reveal the complexity of the Greek characters and the points of divergence between the patterns of violence of rural Greece and Romania. Keywords: rural violence, Karagatsis, balkanism, patterns of violence, homo balcanicus Introduction Research reveals (e.g. Asay, DeFrain, Metzger, Moyer, 2014; NationMaster 2014) both Greece and Romania stand high in terms of violence and anthropologists (e.g. Du Boulay 1986) stress particularly on rural violence. To this we bring our contribution in the following paper, resorting to collective memory and imagery documents as recorded and depicted in literature, to point out some patterns of behaviour that bring these two settings together regarding rural violence. It is not to say other cultural settings cannot be fitted in this frame, but for practical purposes, rigueur, and close ties between these cultural spaces, we have selected Greece and Romanian rural settings. The endeavour is theoretically compelling as much has been argued on the resemblances between Greek and Romanian cultures under the frame of Balkanism. -

Georgiana Galateanu CV

GEORGIANA GALATEANU, a.k.a. FARNOAGA UCLA Department of Slavic, East European and Eurasian Languages and Cultures 322 Kaplan Hall, Box 951502, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1502 [email protected], tel. 310-825-8123 EDUCATION 1999 TESOL/CLAD/TEFL Certificate, UCLA Extension, Lifelong Education Department 1984 Ph.D. in Foreign Language Pedagogy, Foreign Languages Department, University of Bucharest, Romania 1969 M.A., English Language and Literature and Romanian Language and Literature, Foreign Languages Department, University of Bucharest, Romania 1967 B.A., English Language and Literature and Romanian Language and Literature, Foreign Languages Department, University of Bucharest, Romania EMPLOYMENT 1997 to present Continuing Lecturer, Romanian Language, Literature, and Civilization Dept. of Slavic, East European and Eurasian Languages and Cultures, UCLA Courses taught - Romanian 90, Introduction to Romanian Civilization - Romanian 152, Survey of Romanian Literature - Romanian 101 A-B-C, Elementary Romanian - Romanian 103, Intensive Elementary Romanian (Summer Session A) - Romanian 102 A-B-C, Advanced Romanian - Romanian 187 A-M, Advanced Language Tutorial Instruction in Romanian New courses – proposed, developed & taught - C&EE ST 91 (General Education/Central and East European Studies pre-requisite): Culture and Society in Central and Eastern Europe - M120 (Multi-listed Upper Division seminar): Women and Literature in Southeastern Europe - Fiat Lux seminar: Slavic 19. Politics and Literature in Eastern Europe - Applied Linguistics 119/219: -

20 De Scriitori TIPAR.Qxp

20 ROMANIAN WRITERS 20 ROMANIAN WRITERS Translations from the Romanian by Alistair Ian Blyth Artwork by Dragoş Tudor © ROMANIAN CULTURAL INSTITUTE CONTENT Gabriela Adameşteanu 6 Daniel Bănulescu 12 M. Blecher 18 Mircea Cărtărescu 22 Petru Cimpoeşu 28 Lena Constante 34 Gheorghe Crăciun 38 Filip Florian 42 Ioan Groşan 46 Florina Ilis 50 Mircea Ivănescu 56 Nicolae Manolescu 62 Ion Mureşan 68 Constantin Noica 74 Răzvan Petrescu 80 Andrei Pleşu 86 Ioan Es. Pop 92 N. Steinhardt 98 Stelian Tănase 102 Ion Vartic 108 Gabriela Adameşteanu Born 1942. Writer and translator. Editor-in-chief of the Bucureştiul cultural supplement of 22 magazine. Published volumes: The Even way of Every Day (1975), Give Yourself a Holiday (1979), Wasted Morning (1983) (French translation, Éditions Gallimard, 2005), Summer-Spring (1989), The Obsession of Politics (1995), The Two Romanias (2000), The Encounter (2004) Romanian Writers’ Union Prize for Debut, Romanian Academy Prize (1975), Romanian Writers’ Union Prize for Novel (1983), Hellman Hammet Prize, awarded by Human Rights Watch (2002), Ateneu literary review and Ziarul de Iaşi Prize for the novel The Encounter (2004) 6 7 The starched bonnet of Madame Ana moves over Oh, our stable, mediocre familial sentiments, of the tea table, then into the middle of the room, which it would seem you are not worthy, as long next to the tall-legged tables. On each of them she as you cannot prevent yourself from seeing the places a five-armed candelabra and, after hesitating one close to you! From seeing him and, on seeing “Wasted Morning … is one of the best novels to have been published in recent him, from falling into the sin of judging years: rich, even dense, profound, ‘true’ in the most minute of details, modern in its him! construction, and written with finesse. -

74323965.Pdf

Per la riuscita del lavoro, ringrazio di cuore i professori Giovanna Motta e Antonello Biagini A loro, che mi guidano con sapienza e impegno, la mia riconoscenza e la mia ammirazione Niente sarebbe stato possibile senza il sostegno costante e prezioso di Alessandro A lui, che accompagna il mio percorso, i miei sentimenti più sinceri Incondizionato l’amore e la fiducia dei miei genitori Tutto lo devo a loro Indispensabili i consigli del professor Giorgos Freris e l’affetto degli amici Senza di loro la mia strada sarebbe stata incompleta Tante sono state le conoscenze che ho fatto attraverso la ricerca Ringrazio tutti per la loro essenziale collaborazione A Panait Istrati e alla sua incredibile personalità Tento di dare qui il mio piccolo contributo Innescando il suo spirito appassionato di libertà. Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza” L’emigrazione intellettuale dall’Europa centro-orientale Il caso di Panait Istrati Dottorato di Ricerca in Storia d’Europa - XXIV Ciclo Coordinatore Prof.ssa Giovanna Motta Tutor Prof.ssa Giovanna Motta Candidata Elena Dumitru Indice Introduzione 4 I. Un quadro storico. La Grande Romania e l’Europa di Versailles 16 I.1. Il consolidamento della Rivoluzione e il “cordon sanitaire” 22 I.2. Versailles e la nascita della Grande Romania 34 I.3. Stalin e il comunismo internazionale 54 I.4. La nuova destra europea tra fascismo e nazionalsocialismo 69 II. Il caso di Panait Istrati 81 II.1. Dalla Romania alla Francia. Gli inizi 83 II.2.L’incontro con Romain Rolland 90 II.3. L’anno 1927 94 III. In Unione Sovietica. -

Translation and Dissemination in Postcommunist Romanian Literature

CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2012 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 2 2012 Vol IX No 2 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages OLOGY the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are I judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- LOSOPHY OF I ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AX AND CULTURE ONAL JOURNAL OF PH I INTERNAT ISBN 978-3-631-62905-5 www.peterlang.de PETER LANG CULTURA 2012_262905_VOL_9_No2_GR_A5Br.indd 1 16.11.12 12:39:44 Uhr CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2014 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 1 2014 Vol XI No 1 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY CULTURE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY INTERNATIONAL www.peterlang.com CULTURA 2014_265846_VOL_11_No1_GR_A5Br.indd.indd 1 14.05.14 17:43 Cultura.