Hypothesis on Tararira, Benjamin Fondane's Lost Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

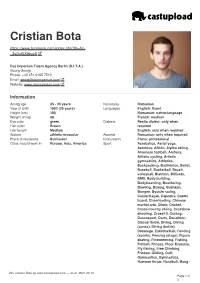

Cristian Bota 3Socf5x9eyz6

Cristian Bota https://www.facebook.com/index.php?lh=Ac- _3sOcf5X9eyz6 Das Imperium Talent Agency Berlin (D.I.T.A.) Georg Georgi Phone: +49 151 6195 7519 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dasimperium.com © b Information Acting age 25 - 35 years Nationality Romanian Year of birth 1992 (29 years) Languages English: fluent Height (cm) 180 Romanian: native-language Weight (in kg) 68 French: medium Eye color green Dialects Resita dialect: only when Hair color Brown required Hair length Medium English: only when required Stature athletic-muscular Accents Romanian: only when required Place of residence Bucharest Instruments Piano: professional Cities I could work in Europe, Asia, America Sport Acrobatics, Aerial yoga, Aerobics, Aikido, Alpine skiing, American football, Archery, Artistic cycling, Artistic gymnastics, Athletics, Backpacking, Badminton, Ballet, Baseball, Basketball, Beach volleyball, Biathlon, Billiards, BMX, Body building, Bodyboarding, Bouldering, Bowling, Boxing, Bujinkan, Bungee, Bycicle racing, Canoe/Kayak, Capoeira, Caster board, Cheerleading, Chinese martial arts, Climb, Cricket, Cross-country skiing, Crossbow shooting, CrossFit, Curling, Dancesport, Darts, Decathlon, Discus throw, Diving, Diving (apnea), Diving (bottle), Dressage, Eskrima/Kali, Fencing (sports), Fencing (stage), Figure skating, Finswimming, Fishing, Fistball, Fitness, Floor Exercise, Fly fishing, Free Climbing, Frisbee, Gliding, Golf, Gymnastics, Gymnastics, Hammer throw, Handball, Hang- Vita Cristian Bota by www.castupload.com — As of: 2021-05-10 -

Mihai Mărgineanu

Festivalul International Multicultural Callatis Fest 11 – 16 August 2015 Olimp - Mangalia Trafic: 100.000 participanti Membru FIDOF, International Federation of Festival Organizations Parteneri: Primaria Mangalia Asociatia de Turism Sudul Litoralului ICR Bucharest Fashion Week, Fashion TV Parteneri media: TVR, KISS FM, Adevarul, Evenimentul, Etiquette, Ring, Antena Stars, Spectator, Agentia de carte Trofeele Callatis 2015 by Patrick Mateescu • Trofeele CallatisFest oferite unor personalitati ale vietii culturale si sociale vor fi realizate de marele sculptor american de origine romana Patrick Mateescu. • Statueta va fi o replica de cca 30 de cm modelata din ceramica aurita, a statuii monumentale aflata pe malul marii, langa Hotel Paradiso, care il reprezinta pe Mihai Eminescu, poetul nepereche, de la a carui nastere aniversam 165 de ani. "Sudul litoralului este important pentru mine pentru că înseamnă mai mult decat mare. Inseamnă și aviație. Am speranța ca turismul in România se va dezvolta în anii ce vor veni, iar Festivalul Callatis trebuie sa continue și să devină un brand de țară." Mihai Mărgineanu “Am avut bucuria să-mi fie daruită o Stea pe Aleea Stelelor de Mare si trofeul, pe scena plutitoare. Festivalul aniversează 18 ani de existență stralucitoare, longevitate ce atestă efort, dăruire și muzică bună într-un decor feeric, natural.” Margareta Pâslaru "Suntem onorați că am fost invitati la Callatis Fest 2015. Abia asteptăm sa concertăm în fața publicului din Mangalia și să sărbătorim împreună cei 30 de ani de carieră." Cargo “În 2009 la Callatis am fost primită cu brațele deschise! Oamenii sunt speciali și calzi. Mangalia este orașul meu de suflet unde mi-am petrecut adolescența și anii de liceu! Abia aștept să mă reintorc! Mă leagă multe amintiri frumoase!” Inna Festival la majorat Un “tânăr” cu tradiție, multicultural, iubit național și de diaspora încă din 1997. -

Romanian Films

Coperta_RomFilm2020.pdf 2 07.02.2020 18:31:23 !"#$ % !"!" ROMANIAN FILMS !"#$ % !"!" ROMANIAN FILM PROMOTION !"#$ % & MINORITY CO'PRODUCTIONS !"#$ % #$ !"!" % !( MINORITY CO'PRODUCTIONS !"!" % )$ IN DEVELOPMENT * PRODUCTION * POST'PRODUCTION !"!" % ($ ROMANIAN FILMS INDEX % +& 2019 !GANG: ANOTHER KIND OF CHRISTMAS !GANG: UN ALTFEL DE CRĂCIUN Directed by: Matei Dima Screenplay: Radu Alexandru, Vali Dobrogeanu, Matei Dima Producers: Anca Truţă, Christmas is near and Selly, who has just Ştefan Lucian, Matei Dima met Corneliu Carafă, vanishes into thin air. Selly’s band colleagues first think that Cast: Selly, Diana Condurache, Gami, Pain, they should replace him with another Cosmin Nedelcu, Julia Marcan, Matei Dima singer, but soon it becomes apparent that Selly may very well be in danger. A great CONTACTS: Vertical Entertainment adventure begins! [email protected] $/ MIN NATIONAL RELEASE DATE: DECEMBER !+, !"#$ ARREST AREST Directed by: Andrei Cohn Screenplay: Andrei Cohn Producer: Anca Puiu Cast: Alexandru Papadopol, Iulian Postelnicu, András Hatházi, Sorin Cociș August, 1983. Architect Dinu Neagu, his wife and the two children spend a few Main Selection: Karlovy Vary IFF 2019 days on a nude beach near an industrial area. Dinu is arrested and taken to the Other films by the director: Bucharest police office, where he is put in Back Home (2015) a cell together with Vali, a collaborator of the Securitate. As days go by, things will CONTACTS: Mandragora get more and more absurd... [email protected] #!/ MIN NATIONAL RELEASE DATE: SEPTEMBER !", !"#$ PRODUCTION COMPANY: MANDRAGORA 4 BEING ROMANIAN: A FAMILY JOURNAL * JURNALUL FAMILIEI #ESCU Directed by: Şerban Georgescu Screenplay: Şerban Georgescu Producer: Şerban Georgescu The story of millions of Romanians who Cast: Ioana Pârvulescu, have ended up living between these Mihaela Miroiu, Sorin Ioniţă borders and having to stand each other: just the way things happen in every large Other films by the director: Cabbage, family. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

New Romanian Cinema

NOVEMBer 29–DECEMBer 3, 2013 Romanian Film Initiative NEW ROMANIAN CINEMA EMA N I C MAKING WAVES: New Romanian Cinema is MAKING WAVES 2013 is made possible with the N IA N co-presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center leading support of the Trust for Mutual Understand- and the Romanian Film Initiative, in partnership ing, Alexandre Almăjeanu and Gentica Foundation, OMA R with the Jacob Burns Film Center and Transilvania Adrian Porumboiu, HBO Romania, Adrian Giurgea, International Film Festival. Colgate University & Christian A. Johnson Founda- S: NEW Launched in 2006 at the initiative of Corina tion, Blue Heron Foundation, Mica Ertegun, Marie WAVE Șuteu, MAKING WAVES has become a fixture in France Ionesco, Lucian Pintilie, Dr. Daiana Voiculescu NG New York City’s cultural scene. The festival offers and Renzo Cianfanelli, and other generous sponsors I K every year the best selection of contemporary and donors, including visual artists Șerban Savu, Dan MA Romanian filmmaking, and introduces American Perjovschi, Adrian Ghenie, and Mircea Cantor. audiences to films and filmmakers who laid the Special support from ICON Production, Lark ground for the new Romanian cinema. Play Development Center, Șapte Seri, Dilema For the second consecutive year, MAKING veche, Radio Guerilla, and filmmaker Mona WAVES is now a fully independent festival of Nicoară, joined by more than 250 supporters. Romanian contemporary cinema and culture, made The “Creative Freedom through Cinema” spe- possible solely through the support of private funders cial program is presented in partnership with the and individual donations, including a large number of Romanian National Film Center, Czech Center New Romanian artists who believe that audiences at home York and the Slovak Film Institute. -

Download Programme PDF Format

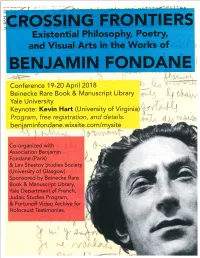

CROSSING FRONTIERS EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY, POETRY, AND VISUAL ARTS IN THE WORKS OF BENJAMIN FONDANE BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY YALE UNIVERSITY APRIL 19-20, 2018 Keynote Speaker: Prof. Kevin Hart, Edwin B. Kyle Professor of Christian Studies, University of Virginia Organizing Committee: Michel Carassou, Thomas Connolly, Julia Elsky, Ramona Fotiade, Olivier Salazar-Ferrer Administration: Ann Manov, Graduate Student & Webmaster Agnes Bolton, Administrative Coordinator “Crossing Frontiers” has been made possible by generous donations from the following donors: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, Yale University Judaic Studies Program, Yale University Department of French, Yale University The conference has been organized in conjunction with the Association Benjamin Fondane (Paris) and the Lev Shestov Studies Society (University of Glasgow) https://benjaminfondane.wixsite.com/mysite THURSDAY, APRIL 19 Coffee 10.30-11:00 Panel 1: Philosophy and Poetry I 11.00-12.30 Room B 38-39 Chair: Alice Kaplan (Yale University) Bruce Baugh (Thompson Rivers University), “Benjamin Fondane: From Poetry to a Philosophy of Becoming” Olivier Salazar-Ferrer (University of Glasgow), “Revolt and Finitude in the Representation of Odyssey” Michel Carassou (Association Benjamin Fondane), “De Charlot à Isaac Laquedem. Figures de l’émigrant dans l’œuvre de Benjamin Fondane” [in French] Lunch in New Haven 12.30-14.30 Panel 2: Philosophy and Poetry II 14.30-16.00 Room B 38-39 Chair: Maurice Samuels (Yale University) Alexander Dickow (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University), “Rhetorical Impurity in Benjamin Fondane’s Poetic and Philosophical Works” Cosana Eram (University of the Pacific), “Consciousness in the Abyss: Benjamin Fondane and the Modern World” Chantal Ringuet (Brandeis University), “A World Upside Down: Marc Chagall’s Yiddish Paradise According to Benjamin Fondane” Keynote 16.15 Prof. -

Presseheft (Pdf)

ONE FLOOR BELOW UN ETAJ MAI JOS von Radu Muntean Rumänien / Frankreich / Deutschland / Schweden 2015, 93 Minuten, cinemascope, OV/df KINOSTART: 21. April Verleih Presse Gasometerstrasse 9 – 8005 Zürich Prosa Film – Rosa Maino Tel: 044 440 25 44 [email protected] [email protected] – www.looknow.ch office 044 296 80 60 – mobile 079 409 46 04 Synopsis Als Pătrașcu nach Hause kommt, hört er hinter der Tür im zweiten Stock seines Wohnhauses einen heftigen Beziehungskrach. Ein paar Stunden später wird die Leiche einer Frau entdeckt. Sein Verdacht fällt auf Vali, den Nachbarn vom ersten Stock. Trotzdem geht Pătrașcu nicht zur Polizei... auch dann nicht, als Vali sich in sein und das Leben seiner Familie einzumischen beginnt. Ein höchst subtiles und gekonnt inszeniertes psychologisches Drama über einen Mann, der mit seinem Gewissen im Unreinen ist. Von spröder Poesie, spannend bis zur letzten Minute. Knapper packender Anti-Thriller. Variety ONE FLOOR BELOW oder die Hölle der Feigheit. Radu Muntean bringt einen intelligenten beinahe gleichmütigen Film heraus, in welchem die Kunst des Understatements auf die Spitze getrieben wird, eine moralische Geschichte, deren Pessimismus in ihrer Hellsichtigkeit Entsprechung findet. Le Monde Ein atemberaubender Psychothriller über die Schuldhaftigkeit - von einer der Schlüsselfiguren der rumänischen Nouvelle-Vague. Les Inrockuptibles Die Subtilität des Charakterzuges ist der Art geschuldet, mit welcher der Schauspieler Teodor Corban seiner Verkörperung der Figur Pătrașcus intime Schattierungen verleiht. Libération Einnehmendes Sozialdrama (...) starkes Kino der Digression, in dem sich die spannendsten Dinge ausserhalb der Leinwand ereignen. FRAME Radu Muntean, Meister des falschen Scheins, legt einen verstörenden und einzigartigen Krimi vor. Le Figaro Eine intensive, minimalistisch inszenierte Psychostudie der erstarrten und um ihre Besitzstände bangenden rumänischen Mittelschicht. -

“Closer to the Moon”, the Big Winner of the Gopo Awards 2015

“Closer to the Moon”, the big winner of the Gopo Awards 2015 Tuesday, March 31, 2015 Gopo Awards Gala, organised on Monday 30 March at the National Theatre in Bucharest, was dominated by director Nae Caranfil's film, "Closer to the Moon", which left the ceremony with 9 prizes. The prize for film direction, received by Nae Caranfil personally, was awarded by the chief executive officer of Dacia, Nicolas Maure. Another remarkable film which won no less than 5 prizes was “Quod Erat Demonstrandum (QED)”, directed by Andrei Gruzsniczki. “I am honoured to be here and to see many personalities stepping down on the red carpet from Dacia cars. I said in an interview for Ziarul Financiar that Romania also needs other image vectors in addition to Dacia. Film is a very good ambassador of Romania abroad, particularly in Europe, and I encourage you to make many good films to get as many awards as possible”, said Nicolas Maure. The award winners of the evening included: Florin Piersic jr (best actor in the leading role), Ofelia Popii (best actress in a leading role), Virgil Ogăşanu (best actor in a supporting role), Alina Berzunţeanu (best actress in a supporting role), film director Alexander Nanău (the best documentary film “Toto and his sisters”), Radu Jude (best fiction short film). The organisers also awarded two prizes for the entire career to actresses Coca Bloos and Eugenia Bosânceanu. The event, presented by Paul Ipate and Diana Cavaliotti, was broadcast live on TVR2 and attracted many participants from the cinema, theatre, media, television and the business environment. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Doru POP the “Trans National Turn”. New Urban Identities

The “Trans national Turn”. 9 New Urban Identities and theI. TransformationCreating of thethe Romanian Space Contemporary Cinema Doru POP The “Trans national Turn”. New Urban Identities and the Transformation of the Romanian Contemporary Cinema Abstract The pressure of globalization and the transformations of the international film markets are rapidly changing the recent Romanian cinema. In a period spanning from 2010 to 2014, the paper describes same of the most important transformations, visible early on in productions like Marţi după Crăciun (Tuesday after Christmas) and even more importantly in a film like Poziţia copilului (Child’s Pose). The process, called by the author “the transnational turn” of the Romanian film, is characterized by the fact that urban spaces become more and more neutral and generic and the stories are increasingly de-contextualized. Designed for international markets, these films are changing both the set- ting and the mise-en-scène, creating a non specific space which is more likely to be accepted by cinema goers around the world. The second argument is the present generation Romanian cinema makers are moving even further, they are choosing to abandon the national cinema. As Elisabeth Ezra and Terry Rowden noted in their introduction to the classical reader on “transnational cinema”, another major aspect is that the recent films are increasingly indicating a certain “Hollywoodization” of their storytelling, and, implicitly, of the respective urban contexts of their narratives. This impact goes beyond genrefication, and, as is the case with productions like Love building (2013), which are using both cosmopolitan behaviors and non-specific urban activities, are manifestations of deep transformations in the Romanian cinema. -

Biblioteca Naţională a României Centrul Naţional ISBN-ISSN-CIP Bd

BIBLIOTECA NAŢIONALĂ A ROMÂNIEI CENTRUL NAŢIONAL CIP BIBLIOGRAFIA CĂRŢILOR ÎN CURS DE APARIŢIE CIP Anul XVI, nr. 12 decembrie 2013 Editura Bibliotecii Naţionale a României Bucureşti 2013 Redacţia: Biblioteca Naţională a României Centrul Naţional ISBN-ISSN-CIP Bd. Unirii, nr. 22, sector 3 Bucureşti, cod 030833 Tel.: 021/311.26.35 Fax: 021/312.49.90 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.bibnat.ro ISSN = 2284 - 8401 ISSN-L = 1453 - 8008 Redactor responsabil: Nicoleta Corpaci Notă: Descrierile CIP sunt realizate exclusiv pe baza informaţiilor furnizate de către editori. Centrul Naţional CIP nu-şi asumă responsabilitatea pentru modificările ulterioare redactării descrierilor CIP şi a numărului de faţă. © 2013 Toate drepturile sunt rezervate Editurii Bibliotecii Naţionale a României. Nicio parte din aceasta lucrare nu poate fi reprodusă sub nicio formă, fără acordul prealabil, în scris, al redacţiei. 4 BIBLIOGRAFIA CĂRŢILOR ÎN CURS DE APARIŢIE CUPRINS 0 GENERALITĂŢI...............................................................................................8 004 Calculatoare. Prelucrarea datelor...............................................................8 006 Standardizare. Metrologie........................................................................15 008 Civilizaţie. Cultură...................................................................................16 01 Bibliografii. Cataloage...............................................................................20 02 Biblioteconomie. Biblioteci.......................................................................21 -

Cetate Nov 2006.Qxd

Reviistã de cullturã,, lliiteraturã ºii artã Seria a III-a An VII, Nr. 2 (59) noiembrie 2006 Cluj-Napoca CUPRINS Cristian W. SCHENK: Cultura în sec. XXI 3 Teofil RÃCHIÞEANU: Temeri 6 Ion ISTRATE: Italienistica româneascã (II) 7 Gheorghe CHIVU: Inedite 22 Miron SCOROBETE: Din jurnalul intim (II) 24 Dr. Ioan Marin MÃLINAª: Patriarhia Ecumenicã a Constantinopolului dupã 29 mai 1453 37 Tudor NEGOESCU: Poezii de întuneric 47 Vistian GOIA: Poezia floralã româneascã 49 Hanna BOTA: O cãlãtorie la Auschwitz-Birkenau 58 Ion MARIA: Poezia 64 Mircea GOGA: Laurenþiu Hodorog ºi tinereþea fãrã bãtrâneþe a Clujului cultural 65 Mihail DIACONESCU: ªtiinþa ºi arta portretului literar 70 Aurel PODARU: Zãluda 77 Ion CRISTOFOR: De la poetica la eticã: Claire Lejeune 82 Emanuel GIURGIUMAN: Cultura tracicã ºi semnificaþiile ei antropologice 85 Dan BRUDAªCU: Poeþi din Laos 95 Din lucr@rile ap@rute la Editura SEDAN din Cluj-Napoca 2 Criistiian W.. SCHENK CULTURA ÎN SECOLUL XXI „Globalizare” devenitã între timp lozincã, parolã, devizã cu iz de cuvânt de spirit sau efect, circulã fantomatic prin toate mediile, cu preponderenþã în cele electronice. Aici nu poate fi vorba doar de o raportare la culturã ci mai mult, cultura va fi implicatã în politicã, economie sau sociologie, o formã de cuplare transnaþionalã a tuturor sistemelor ºi a societãþilor. Statele reacþioneazã, privind globalizarea, prin mãrirea atractivitãþii teritoriului lor ca puncte de concentrare al capitalului, mãrirea exportului naþional, distribuþia mondialã a tuturor bunurilor individuale. Reducerea la o piaþã naþionalã ar sta în contradicþie cu ideea de globalizare. Doar prin implicarea politicii, a economiei ºi nu în cele din urmã a sociologiei se va putea vorbi ºi de ideea de globalizare a culturii sau mai exact efectele ce le va avea asupra culturii.