Fall of Xiong-Nu and Rise of Manchurian Nomad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From?

客家 My China Roots & CBA Jamaica An overview of Hakka Migration History: Where are you from? July, 2016 www.mychinaroots.com & www.cbajamaica.com 15 © My China Roots An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From? Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 3 Five Key Hakka Migration Waves............................................................................................. 3 Mapping the Waves ....................................................................................................................... 3 First Wave: 4th Century, “the Five Barbarians,” Jin Dynasty......................................................... 4 Second Wave: 10th Century, Fall of the Tang Dynasty ................................................................. 6 Third Wave: Late 12th & 13th Century, Fall Northern & Southern Song Dynasties ....................... 7 Fourth Wave: 2nd Half 17th Century, Ming-Qing Cataclysm .......................................................... 8 Fifth Wave: 19th – Early 20th Century ............................................................................................. 9 Case Study: Hakka Migration to Jamaica ............................................................................ 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 11 Context for Early Migration: The Coolie Trade........................................................................... -

Chronology of Chinese History

Chronology of Chinese History I. Prehistory Neolithic Period ca. 8000-2000 BCE Xia (Hsia)? Trad. 2200-1766 BCE II. The Classical Age (Ancient China) Shang Dynasty ca. 1600-1045 BCE (Trad. 1766-1122 BCE) Zhou (Chou) Dynasty ca. 1045-256 BCE (Trad. 1122-256 BCE) Western Zhou (Chou) ca. 1045-771 BCE Eastern Zhou (Chou) 770-256 BCE Spring and Autumn Period 722-468 BCE (770-404 BCE) Warring States Period 403-221 BCE III. The Imperial Era (Imperial China) Qin (Ch’in) Dynasty 221-207 BCE Han Dynasty 202 BCE-220 CE Western (or Former) Han Dynasty 202 BCE-9 CE Xin (Hsin) Dynasty 9-23 Eastern (or Later) Han Dynasty 25-220 1st Period of Division 220-589 The Three Kingdoms 220-265 Shu 221-263 Wei 220-265 Wu 222-280 Jin (Chin) Dynasty 265-420 Western Jin (Chin) 265-317 Eastern Jin (Chin) 317-420 Southern Dynasties 420-589 Former (or Liu) Song (Sung) 420-479 Southern Qi (Ch’i) 479-502 Southern Liang 502-557 Southern Chen (Ch’en) 557-589 Northern Dynasties 317-589 Sixteen Kingdoms 317-386 NW Dynasties Former Liang 314-376, Chinese/Gansu Later Liang 386-403, Di/Gansu S. Liang 397-414, Xianbei/Gansu W. Liang 400-422, Chinese/Gansu N. Liang 398-439, Xiongnu?/Gansu North Central Dynasties Chang Han 304-347, Di/Hebei Former Zhao (Chao) 304-329, Xiongnu/Shanxi Later Zhao (Chao) 319-351, Jie/Hebei W. Qin (Ch’in) 365-431, Xianbei/Gansu & Shaanxi Former Qin (Ch’in) 349-394, Di/Shaanxi Later Qin (Ch’in) 384-417, Qiang/Shaanxi Xia (Hsia) 407-431, Xiongnu/Shaanxi Northeast Dynasties Former Yan (Yen) 333-370, Xianbei/Hebei Later Yan (Yen) 384-409, Xianbei/Hebei S. -

China's Place in Philology: an Attempt to Show That the Languages of Europe and Asia Have a Common Origin

CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT Of CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF IB76 1918 Cornell University Library P 201.E23 China's place in phiiologyian attempt toI iPii 3 1924 023 345 758 CHmi'S PLACE m PHILOLOGY. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023345758 PLACE IN PHILOLOGY; AN ATTEMPT' TO SHOW THAT THE LANGUAGES OP EUROPE AND ASIA HAVE A COMMON OKIGIIS". BY JOSEPH EDKINS, B.A., of the London Missionary Society, Peking; Honorary Member of the Asiatic Societies of London and Shanghai, and of the Ethnological Society of France, LONDON: TRtJBNEE & CO., 8 aito 60, PATEENOSTER ROV. 1871. All rights reserved. ft WftSffVv PlOl "aitd the whole eaeth was op one langtta&e, and of ONE SPEECH."—Genesis xi. 1. "god hath made of one blood axl nations of men foe to dwell on all the face of the eaeth, and hath detee- MINED the ITMTIS BEFOEE APPOINTED, AND THE BOUNDS OP THEIS HABITATION." ^Acts Xvil. 26. *AW* & ju€V AiQionas fiereKlaOe tij\(J6* i6j/ras, AiOioiras, rol Si^^a SeSafarat effxarot av8p&Vf Ol fiiv ivffofievov Tireplovos, oi S' avdv-rof. Horn. Od. A. 22. TO THE DIRECTORS OF THE LONDON MISSIONAEY SOCIETY, IN EECOGNITION OP THE AID THEY HAVE RENDERED TO EELIGION AND USEFUL LEAENINO, BY THE RESEARCHES OP THEIR MISSIONARIES INTO THE LANGUAOES, PHILOSOPHY, CUSTOMS, AND RELIGIOUS BELIEFS, OP VARIOUS HEATHEN NATIONS, ESPECIALLY IN AFRICA, POLYNESIA, INDIA, AND CHINA, t THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. -

The Zhuan Xupeople Were the Founders of Sanxingdui Culture and Earliest Inhabitants of South Asia

E-Leader Bangkok 2018 The Zhuan XuPeople were the Founders of Sanxingdui Culture and Earliest Inhabitants of South Asia Soleilmavis Liu, Author, Board Member and Peace Sponsor Yantai, Shangdong, China Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people (or tribes) in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Zhuan Xu, Di Jun, Huang Di, Yan Di and Shao Hao.However, the Zhuan Xu People seemed to have disappeared when the Yellow and Chang-jiang river valleys developed into advanced Neolithic cultures. Where had the Zhuan Xu People gone? Abstract: Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Zhuan Xu, Di Jun, Huang Di, Yan Di and Shao Hao. These were not only the names of individuals, but also the names of groups who regarded them as common male ancestors. These groups used to live in the Pamirs Plateau, later spread to other places of China and built their unique ancient cultures during the Neolithic Age. Shanhaijing reveals Zhuan Xu’s offspring lived near the Tibetan Plateau in their early time. They were the first who entered the Tibetan Plateau, but almost perished due to the great environment changes, later moved to the south. Some of them entered the Sichuan Basin and became the founders of Sanxingdui Culture. Some of them even moved to the south of the Tibetan Plateau, living near the sea. Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed the authenticity of Shanhaijing ’s records. Keywords: Shanhaijing; Neolithic China, Zhuan Xu, Sanxingdui, Ancient Chinese Civilization Introduction Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan

THE HISTORY OF GYALTHANG UNDER CHINESE RULE: MEMORY, IDENTITY, AND CONTESTED CONTROL IN A TIBETAN REGION OF NORTHWEST YUNNAN Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Michael Tsin Michelle T. King Ralph A. Litzinger W. Miles Fletcher Donald M. Reid © 2016 Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii! ! ABSTRACT Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen: The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan (Under the direction of Michael Tsin) This dissertation analyzes how the Chinese Communist Party attempted to politically, economically, and culturally integrate Gyalthang (Zhongdian/Shangri-la), a predominately ethnically Tibetan county in Yunnan Province, into the People’s Republic of China. Drawing from county and prefectural gazetteers, unpublished Party histories of the area, and interviews conducted with Gyalthang residents, this study argues that Tibetans participated in Communist Party campaigns in Gyalthang in the 1950s and 1960s for a variety of ideological, social, and personal reasons. The ways that Tibetans responded to revolutionary activists’ calls for political action shed light on the difficult decisions they made under particularly complex and coercive conditions. Political calculations, revolutionary ideology, youthful enthusiasm, fear, and mob mentality all played roles in motivating Tibetan participants in Mao-era campaigns. The diversity of these Tibetan experiences and the extent of local involvement in state-sponsored attacks on religious leaders and institutions in Gyalthang during the Cultural Revolution have been largely left out of the historiographical record. -

The History of the History of the Yi, Part II

MODERNHarrell, Li CHINA/ HISTORY / JULY OF 2003THE YI, PART II REVIEW10.1177/0097700403253359 Review Essay The History of the History of the Yi, Part II STEVAN HARRELL LI YONGXIANG University of Washington MINORITY ETHNIC CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE 1980S AND 1990S The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is, according to its constitution, “a unified country of diverse nationalities” (tongyide duominzu guojia; see Wang Guodong, 1982: 9). The degree to which this admirable political ideal has actually been respected has varied throughout the history of the PRC: taken seriously in the early and mid-1950s, it was systematically ignored dur- ing the twenty years of High Socialism from the late 1950s to the early 1980s and then revived again with the Opening and Reform policies of the past two decades (Heberer, 1989: 23-29). The presence of minority “autonomous” ter- ritories, preferential policies in school admissions, and birth quotas (Sautman, 1998) and the extraordinary emphasis on developing “socialist” versions of minority visual and performing arts (Litzinger, 2000; Schein, 2000; Oakes, 1998) all testify to serious attention to multinationalism in the cultural and administrative realms, even if minority culture is promoted in a homogenized socialist version and even if everybody knows that “autono- mous” territories are far less autonomous, for example, than an American state or a Swiss canton. But although the party state now preaches multinationalism and allows limited expression of ethnonational autonomy, it also preaches and promotes progress—and thus runs straight into a paradox: progress is defined in objectivist, modernist terms, which relegate minority cultures to a more MODERN CHINA, Vol. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02077-1 — The Cambridge History of China Edited by Albert E. Dien , Keith N. Knapp Excerpt More Information INTRODUCTION Periods of disunity in Chinese history do not usually receive the attention they deserve, yet it is just in those years of apparent disorder and even chaos that important developments, social, cultural, artistic, and even institutional, often find their earliest expression. The Six Dynasties period (220–589 ce) was just such a time of momentous changes in many aspects of the society. But it is precisely the confusing tumult and disorder of the political events of those four centuries that create the strongest impression. We find this perception mir- rored in the reaction of the put-upon Gao Laoshi, the middle-school school- master described by Lu Xun in one of his stories, who was so dejected when he had been assigned to teach a course on the Six Dynasties. All he remembered about the subject was how very confusing it was, a time of much warfare and turmoil; no doubt what would have come to his mind was the common saying wu Hu luan Hua 五胡亂華 “the Five Barbarians brought disorder to China.” He felt that he could do a creditable job with the great Han and Three Kingdoms that came before or the glorious Tang after it, but what could he say about those miserable years in between?1 The very nomenclature reflects its apparent disjointed nature. Yet it was that very disorder, a collapse of central authority, that provided the conditions enabling such important advances which make the Six Dynasties period such a significant one in Chinese history. -

The Urban Mind Cultural and Environmental Dynamics

The Urban Mind Cultural and Environmental Dynamics Edited by Paul J.J. Sinclair, Gullög Nordquist, Frands Herschend and Christian Isendahl African and Comparative Archaeology Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 2010 Cover: NMH THC 9113 Artist: Cornelius Loos Panorama over the southern side of Istanbul facing north east. Produced in 1710. Pen and brush drawing with black ink, grey wash, water colour on paper. The illustration is composed of nine separate sheets joined together and glued on woven material. Original retouching glued along the whole length of the illustration. Dimensions (h x b) 28,7 x 316 cm Photograph © Erik Cornelius / Nationalmuseum English revised by Laura Wrang. References and technical coordination by Elisabet Green. Layout: Göran Wallby, Publishing and Graphic Services, Uppsala university. ISSN 1651-1255 ISBN 978-91-506-2175-4 Studies in Global Archaeology 15 Series editor: Paul J.J. Sinclair. Editors: Paul J.J. Sinclair, Gullög Nordquist, Frands Herschend and Christian Isendahl. Published and distributed by African and Comparative Archaeology, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Box 626, S-751 26 Uppsala. Printed in Sweden by Edita Västra Aros AB, Västerås 2010 – a climate neutral company. 341 009 Trycksak Table of Contents Preface ....................................................................................................... 9 The Urban Mind: A Thematic Introduction Paul J.J. Sinclair .......................................................................... -

The Reconstruction of the Name Yuezhi 月氏 / 月支

International Journal of Old Uyghur Studies, 1/2, 2019: 249-282 The Reconstruction of The Name Yuezhi 月氏 / 月支 Hakan Aydemir* (İstanbul - Türkiye) Dedicated to Prof. Dr. Dieter Michael Job Özet: Yuezhi Adının Yeniden Yapılandırılması Orta Asya tarihinin kuşkusuz en önemli problemlerinden biri Çin kaynaklarında Yuèzhī (月氏 / 月支) olarak geçen halkın kökenidir. Bugüne kadar tarihi veya arkeolojik araştırmalar Yüecilerin kökenini ikna edici bir biçimde açıklayamadılar. Bu çalışma, Yüecilerin kökenine ve Toharlarla ilişkilerine ilişkin çeşitli kuramları tanıtarak onları eleştirel bir yaklaşımla ele almaya çalışıyor. Bu sorunu çözebilmek için Uygur ve Çin yer adlarını inceleyerek Afganistan ve Doğu Türkistan’daki Yüeci boy adı kökenli yer adlarını tespit etmeye çalışıyor. Çalışmanın sonunda, Yüecilerin Afganistan ve Doğu Türkistan’daki eski coğrafi dağılımlarını göstermek için Yüeci boy adı kökenli yer adlarını gösteren iki de harita veriliyor. Boy adı kökenli bu yer adlarına ve tarihsel verilere dayanarak Yuèzhī adının asli biçiminin yeniden kurgulanması yönünde bir deneme de yapılıyor. Anahtar Sözcükler: Yuezhi, Toharlar, Tohar sorunu, Türkçe-Toharca ilişkileri Abstract One of the most important problems of Central Asian history is undoubtedly the origin of the people referred to as Yuèzhī (月氏 / 月支) in Chinese sources. So far, historical or archaeological research could not * Dr., Istanbul Medeniyet University, [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0002-2368-71030000-0002-2368-7103. 250 HAKAN AYDEMİR convincingly explain the origins of the Yuezhi. The study attempts to present and critically evaluate various theories concerning the origin of the Yuezhi and their relationship to the Tocharians. To address this problem, it investigates Uyghur and Chinese place names and tries to list Yuezhi ethnotoponyms in Afghanistan and Xinjiang. -

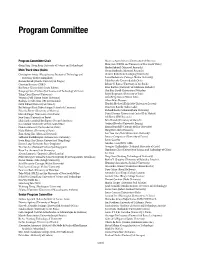

Program Committee

Program Committee Program Committee Chair Mauricio Ayala-Rincón (Universidade de Brasilia) Qiang Yang (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) Haris Aziz (NICTA and University of New South Wales) Moshe Babaioff (Microso Research) Main Track Area Chairs Yoram Bachrach (Microso Research) Christopher Amato (Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Christer Bäckström (Linköping University) University of New Hampshire) Laura Barbulescu (Carnegie Mellon University) Roman Bartak (Charles University in Prague) Pablo Barcelo (Universidad de Chile) Christian Bessiere (CNRS) Leliane N. Barros (University of Sao Paulo) Blai Bonet (Universidad Simón Bolívar) Peter Bartlett (University of California, Berkeley) Xiaoping Chen (University of Science and Technology of China) Shai Ben-David (University of Waterloo) Yiling Chen (Harvard University) Ralph Bergmann (University of Trier) Veronica Dahl (Simon Fraser University) Alina Beygelzimer (Yahoo! Labs) Rodrigo de Salvo Braz (SRI International) Albert Bifet (Huawei) Edith Elkind (University of Oxford) Hendrik Blockeel (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) Boi Faltings (Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne) Francesco Bonchi (Yahoo Labs) Eduardo Ferme (University of Madeira) Richard Booth (Mahasarakham University) Marcelo Finger (University of Sao Paulo) Daniel Borrajo (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid) Joao Gama (University of Porto) Adi Botea (IBM Research) Lluis Godo (Artificial Intelligence Research Institute) Felix Brandt (University of Munich) Jose Guivant (University of New South Wales) Gerhard -

Tang-Song Transition”

Journal of chinese humanities 6 (2020) 192-212 brill.com/joch A Discussion of Several Issues Concerning the “Tang-Song Transition” Mou Fasong 牟發松 Professor of Department of History, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China [email protected] Abstract Naitō Konan’s hypothesis on the “Tang-Song transition” was first expressed in lec- ture notes from his 1909 class on modern Chinese history at Kyoto University and, then, expounded in subsequent works such as “A General View of the Tang and Song Dynasties” and “Modern Chinese History.” The theory systematically outlines that an evolutionary medieval to modern transition occurred in Chinese society during the period between the Tang and the Song dynasties, focusing in particular on the areas of politics/government, the economy, and culture. Political change is regarded as the core metric, demonstrated in concentrated form by the government’s transformation from an aristocratic to a monarchical autocratic system alongside a rise in the status and position of the common people. The “Tang-Song transition theory,” underpinned theo- retically by a cultural-historical perspective, advocates for a periodization of Chinese history based on the stages and characteristics of China’s cultural development, which is also attributed to cultural shifts, downward to the commoner class from a culture monopolized by the aristocracy during the period between the Tang and Song, with concomitant changes in society. For over a century since it was first proposed, the “Tang-Song transition theory” has had far-reaching influence in Chinese, Japanese, and Western academic circles, continuing to be lively and vigorous even now. We might be able to find the cause in its originality and liberality, which leave significant room for later thinkers’ continued adherence and development or criticism and falsi- fication and continue to inspire new questions.