Building Urban Resilience Through Spatial Planning Following Disasters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JR EAST GROUP CSR REPORT 2015 Safety

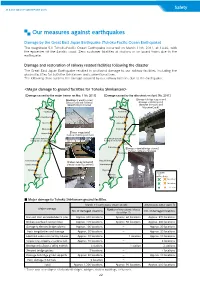

JR EAST GROUP CSR REPORT 2015 Safety Our measures against earthquakes Damage by the Great East Japan Earthquake (Tohoku-Pacific Ocean Earthquake) The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-Pacific Ocean Earthquake occurred on March 11th, 2011, at 14:46, with the epicenter off the Sanriku coast. Zero customer fatalities at stations or on board trains due to the earthquake. Damage and restoration of railway related facilities following the disaster The Great East Japan Earthquake resulted in profound damage to our railway facilities, including the ground facilities for both the Shinkansen and conventional lines. The following chart outlines the damage incurred by our railway facilities due to the earthquake. <Major damage to ground facilities for Tohoku Shinkansen> 【Damage caused by the major tremor on Mar. 11th, 2011】 【Damage caused by the aftershock on April 7th, 2011】 【Breakage of electric poles】 【Damage to bridge supports and (Between Sendai and Shinkansen breakage of electric poles】 General Rolling Stock Center) (Between Ichinoseki and Mizusawa-Esashi) Shin-Aomori Shin-Aomori Hachinohe Hachinohe Iwate-Numakunai Iwate-Numakunai Morioka Morioka Kitakami Kitakami Ichinoseki 【Track irregularity】 (Sendai Station premises) Ichinoseki Shinkansen General Shinkansen General Rolling Stock Center Rolling Stock Center Sendai Sendai Fukushima Fukushima 【Damage to elevated bridge columns】 (Between Sendai and Furukawa) Kōriyama Kōriyama Nasushiobara Nasushiobara 【Fallen ceiling material】 Utsunomiya (Sendai Station platform) Utsunomiya Oyama Oyama 【Legend】 Ōmiya Ōmiya Civil engineering Tōkyō Tōkyō Electricity 50 locations 10 locations 1 location ■ Major damage to Tohoku Shinkansen ground facilities March 11 earthquake (main shock) Aftershocks (after April 7) Major damage Number of not restored places No. of damaged locations No. -

Report on Rebuilding Flood-Conscious Societies in Small

Report on Rebuilding Flood-Conscious Societies in Small and Medium River Basins January 2017 Council for Social Infrastructure Development 1 Contents 1. Introduction - Accelerate Rebuilding Flood-Conscious Societies ............................... 3 2. Typhoons in the Hokkaido and Tohoku regions in August 2016 .................................. 5 2.1 Outline of Torrential Rains ........................................................................................ 5 2.2 Outline of Disaster Damage ....................................................................................... 6 2.3 Features of the Disasters ............................................................................................ 7 3. Small and Medium River Basins under Changing Climate and Declining Populations ................................................................................................................................................ 9 4. Key Activities Based on the Report of December 2015 ................................................ 11 5. Key Challenges to be addressed..................................................................................... 13 6. Measures Needed in Small and Medium River Basins ................................................ 15 6.1 Basic Policy ................................................................................................................ 15 6.2 Measures to be taken ................................................................................................ 17 7. Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... -

Iwate Aomori Iwate Experience 8 Cuisine 10 Festival 11

ENGLISH EDITION TOHOKU TOURIST INFORMATION CENTER NETWORK TOHOKU Round Trip Guide Majestic Nature Historic Landmark Excellent Cuisine Indigenous Festival TOHOKU TOURIST INFORMATION CENTER NETWORK The 42 tourist information centers in the Tohoku region are all connected with an online video chat service. We provide information to you in real time. Shiroishi River and 1000 Cherry Trees, Miyagi Tohoku Regional Collaboraion Promotion Office,Culture and Tourism Bureau, City of Sendai Hokkaido TOHOKU TOURIST INFORMATION CENTER NETWORK INDEX Tohoku, an area surrounded by beautiful nature with four seasons. Aomori Architectures with rich Japanese history, Experience 4 various local cuisine, unique indigenous festivals. Cuisine 6 Experiences only possible in Tohoku await. Festival 7 Iwate Aomori Iwate Experience 8 Cuisine 10 Festival 11 Miyagi Experience 12 Cuisine 14 Aomori Festival 15 Akita Experience 16 Cuisine 18 Tanesashi Coast Jodogahama Beach Festival 19 Miyagi Akita Yamagata Experience 20 Akita Cuisine 22 Iwate Festival 23 Fukushima Experience 24 Cuisine 26 Festival 27 Tourist Information Center 28 Railway 34 Yamagata Miyagi Matsushima Godzilla Rock Yamagata Fukushima Fukushima Mt. Haguro Higashiyama Onsen (Hot Spring) 2 3 Experience Superb View of 2,600 Cherry Trees (Sakura) Aomori and a White-walled Castle Hirosaki Castle Hirosaki Castle in Hirosaki Park, built in the Edo period, has the northernmost castle tower*1 in Japan and is designated as an important national cultural property. Its extensive castle walls in their original form being opened as a park is rare in Japan. There Aomori are about 2,600 Sakura in the park, and many people come for Aomori the blossoms in the spring. -

Japan: Tokai Heavy Rain (September 2000)

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION THE ASSOCIATED PROGRAMME ON FLOOD MANAGEMENT INTEGRATED FLOOD MANAGEMENT CASE STUDY1 JAPAN: TOKAI HEAVY RAIN (SEPTEMBER 2000) January 2004 Edited by TECHNICAL SUPPORT UNIT Note: Opinions expressed in the case study are those of author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the WMO/GWP Associated Programme on Flood Management (APFM). Designations employed and presentations of material in the case study do not imply the expression of any opinion whatever on the part of the Technical Support Unit (TSU), APFM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. WMO/GWP Associated Programme on Flood Management JAPAN: TOKAI HEAVY RAIN (SEPTEMBER 2000) Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Japan 1. Place 1.1 Location Positions in the flood inundation area caused by the Tokai heavy rain: Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture is located at 35° – 35° 15’ north latitude, 136° 45’ - 137° east longitude. The studied area is Shonai and Shin river basin- hereinafter referred to as the Shonai river system. It locates about the center of Japan including Nagoya city area, 5th largest city in Japan with the population about 3millions. Therefore, two rivers flow through densely populated area and into the Pacific Ocean and are typical city-type rivers in Japan. Shin Riv. Border of basin Shonai Riv. Flooding area Point of breach ●Peak flow rate in major points on Sept. 12 (app. m3/s) ← Nagoya City, ← ← ino ino Aichi Prefecture j Ku ← 1,100 Shin Riv. ← 720 ← → ← ima Detention j Basin Shinkawa Araizeki Shidami Biwa (Fixed dam) Shin Riv. -

Handbook for Foreigners Living in Misato English

Handbook for Foreigners Living in Misato English 美里町に暮らす外国人のためのハンドブック ~ 英語版 July 2009 みさとまち Welcome to Misato 美里町へようこそ I would like to welcome you to the Town of Misato – a community dedicated to world peace. If you have this handbook, you no doubt have many hopes and worries about life in Misato. Has leaving you home country, native language and customs created any problems for you? This handbook contains a lot of important information to help make your life easier, even if just a little. Please use this book to help improve your experience here whether at home, for work or study. I pray that you will be able to make many happy memories during your time with us. ひかく へいわ とし みやぎけん みさとまち 非核・平和都市 宮城県美里町へようこそいらっしゃいました。 みな はじ みさとまち せいかつ きたい ふあん おも 皆さんは、これから始まる美里町での生活 への期待と不安でいっぱいのことと思います。 はな ことば しゅうかん ちが にっぽん こま ふるさとを離れ、言葉や習 慣の違う日本で困っていることはありませんか? みな ひつよう じょうほう あつ このハンドブックはそんな皆さんのために、必 要な情 報を集めたものです。 みな まいにち しごと べんきょう かてい せいかつ いとな うえ ごかつよう みさとまち 皆さんの毎日 の仕事や勉強 、そして家庭生活 を営む上で御活用ください。そして美里町 えがお おも で つく こころ いの もう あ でたくさんの笑顔と思い出 を作ってください。心からお祈り申し上げます。 Koetsu Sasaki Mayor of Misato もく じ Table of Contents 目 次 Page 1. About Misato 1 1. 美里町について ① Introduction to Misato 2 ① 美里町の紹介 ② Brief History of Misato 4 ② 美里町の歴史 ③ Important Contacts 5 ③ 主な連絡先 2. Using the Trains 7 2. 鉄道 ① Kanji for Area 8 ① 地名 ② Train Fares 9 ② 電車運賃 ③ Reading a Train Schedule 10 ③ 電車の時刻表 3. Facilities In Misato 11 3. 施設など ① Misato Libraries 12 ① 図書館 ② Community Center 15 ② 公民館 ③ International Groups 16 ③ 国際交流団体 ④ Things to do in Misato 18 ④ 美里で遊ぶ ⑤ Other Facilities and Offices 19 ⑤ その他のお問い合わせ ⑥ Garbage & Recycling 21 ⑥ ゴミの分別 4. -

A Prosperous Future Starts Here

A prosperous future starts here 100% of this paper was made using recycled paper 2018.4 (involved in railway construction) Table of Lines Constructed by the JRTT Contents Tsukuba Tokyo Area Lines Constructed by JRTT… ……………………… 2 Sassho Line Tsukuba Express Line Asahikawa Uchijuku JRTT Main Railway Construction Projects……4 Musashi-Ranzan Signal Station Saitama Railway Line Maruyama Hokkaido Shinkansen Saitama New Urban Musashino Line Tobu Tojo Line Urawa-Misono Kita-Koshigaya (between Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto Transit Ina Line Omiya Nemuro Line Shinrin-Koen and Sapporo) ■ Comprehensive Technical Capacity for Railway Sapporo Construction/Research and Plans for Railway Tobu Isesaki Line Narita SKY ACCESS Line Construction… ………………………………………………6 Hatogaya (Narita Rapid Rail Acess Line) Shiki Shin-Matsudo Hokuso Railway Hokuso Line ■ Railway Construction Process… …………………………7 Takenotsuka Tobu Tojo Line Shin-Kamagaya Komuro Shin-Hakodatehokuto Seibu Wako-shi Akabane Ikebukuro Line Imba Nihon-Idai Sekisho Line Higashi-Matsudo Narita Airport Hakodate …… Kotake-Mukaihara Toyo Rapid Construction of Projected Shinkansen Lines 8 Shakujii-Koen Keisei-Takasago Hokkaido Shinkansen Aoto Nerima- Railway Line Nerima Takanodai Ikebukuro Keisei Main Line (between Shin-Aomori and Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto) Hikifune Toyo- Tsugaru-Kaikyo Line Seibu Yurakucho Line Tobu Katsutadai ■ Kyushu Shinkansen… ………………………………………9 Tachikawa Oshiage Ueno Isesaki Line Keio Line Akihabara Nishi-Funabashi Shinjuku … ………………………………… Odakyu Odawara Line Sasazuka ■ Hokuriku Shinkansen 10 Yoyogi-Uehara -

Rethinking the Safety Philosophy: Yasutake Kojima

Rethinking the Safety Philosophy Yasutake Kojima | Director | June 12, 2017 Copyright 2017 East Japan Railway Company. All rights reserved. One: Overview of JR EAST Two: JR EAST Safety Plan 2018 Three: Establish Safety Cultures TABLE OF CONTENTS Four: Improve Safety Management System Five: Steadily Reducing Risks Six: Prioritize Safety Equipment Planning Seven: Conclusion Copyright 2017 East Japan Railway Company. All rights reserved. 2 OVERVIEW OF JR EAST – Japan is a land of railroads Copyright 2017 East Japan Railway Company. All rights reserved. 3 OVERVIEW OF JR EAST Japanese National Railways Passenger Transport Companies (JNR) 1) JR Hokkaido 2) JR East Transferred in April 1987 3) JR Central 4) JR West 5) JR Shikoku 6) JR Kyushu JNR Settlement Corporation JR Hokkaido Japan Freight Railway Company Territorial division Railway Information System Company JR West Railway Technical Research Institute JR East JR Kyushu JR Central Telecomunication,etc JR Shikoku Copyright 2017 East Japan Railway Company. All rights reserved. 4 OVERVIEW OF JR EAST We own all the infrastructure of railway, operate and maintain as full integration railway model. Infrastructure Operation and Maintenance Tokyo Copyright 2017 East Japan Railway Company. All rights reserved. Titre de la présentation | Prénom NOM, fonction 5 OVERVIEW OF JR EAST We own and operate and High-speed all categories of passenger railway transport. About 7,500 km Integrated Railway Network 57,000 employees Passengers: 17 mil. /day Tokyo Metropolitan Area Copyright 2017 East Japan Railway Company. All rights reserved. Metropolitan Regional6 OVERVIEW OF JR EAST Tokyo Takasaki Line Utsunomiya Utsunomiya Takasaki Oyama Metropolitan Area Kumagaya Line Koga Konosu Kawagoe Tsuchiura Network Line Tohoku Kawagoe freight Line Komagawa Joban Line Toride Omiya Musashino Saikyo Line Ome Line Line Abiko Hachiko Narita Line Minami-Urawa ☆ No. -

We Start Distribution of Train Operation Information Via Twitter Account in English

December 19th, 2019 EAST JAPAN RAILWAY COMPANY We start distribution of train operation information via Twitter account in English ○ JR East provides train operation information via website, JR East app, Twitter, etc., when train delays occur or are expected. ○ Up to now, Twitter train operation information has been distributed only in Japanese. In addition to this, we will start distributing information in English via Twitter account. 1.Scheduled service starting date From around 10:00 on December 24th (Tue), 2019 2.Distribution information If a delay of more than 30 minutes occurs or is expected in the JR East area between 4 o'clock and 2 o'clock on the next day, we will inform the train operation status. In the case of normal train operation, the operation status will be distributed every day at 7am and 5pm. In addition, we will inform BRT service information only when the operation will be suspended for a long time. Screen image of Tokaido area Screen image of Shinkansen 3.Distribution train line The accounts to be distributed and target lines etc., are as follows. Account name Account Target line Tōkaidō Line, Keihin-Tōhoku Line, Yokosuka Line, Nambu Line, Yokohama Line, Itō Line, JREast【Tokaido area】 JRE_Tokaido_E Sagami Line, Tsurumi Line, Yamanote Line, Kanto info(official) Ueno-Tōkyō Line, Shōnan-Shinjuku Line, Through service to Sotetsu Line Utsunomiya Line, Takasaki Line, Keihin-Tōhoku Line, Saikyō Line, Kawagoe Line, Musashino Line, Jōetsu Line(※1), Shin-etsu Line(※1), JREast【Tohoku・Takasaki area】 JRE_Toho_Taka_E Agatsuma -

Damage to the Railway System Along the Coast Due to the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Tsunami

Journal of Natural Disaster Science, Volume 34, Number 1, 2012, pp105-113 Damage to the Railway System along the Coast Due to the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Tsunami Soichiro SHIMAMURA* Fumihiko IMAMURA** Ikuo ABE*** *Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Tohoku University 6-6-11-1106, Aoba, Sendai, 980-8579, JAPAN **International Research Institute of Disaster Science, Tohoku University ***Department of Social Environment, Fuji Tokoha University (Received May 2, 2012 Accepted November 2, 2012) ABSTRACT The enormous Mw 9.0 earthquake with a hypocenter off Sanriku-oki that occurred at approximately 14:46 (JST) on March 11, 2011, and the subsequent tsunami, caused serious damage along the Pacific coast of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima. The damage to infrastructure was remarkable, and the damage to the railway caused by the tsunami was the greatest damage ever to occur to the railway. JR-East reported that they checked the damage caused by only the tsunami along seven lines, which had a total distance of 325 km, and the form of damage varied by line. This paper summarizes the damage to the railway (including damage to vehicles) and the evacuation guidance situation for each line and investigates how the trains were damaged based on the numerical analysis of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Tsunami. Keyword: The 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Tsunami, Train, Numerical Analysis 1. Introduction was checked along 7 provincial routes over a total of approximately 325 km. On 2011 March 11th 14:46 (JST), an enormous Mw This paper presents an outline of the 2011 Tohoku 9.0 earthquake occurred with a seismic center on the Earthquake Tsunami, and, because the degree and coast of Sanriku. -

High-Resolution Mapping of Japanese Microplastic and Macroplastic Emissions from the Land Into the Sea

water Article High-Resolution Mapping of Japanese Microplastic and Macroplastic Emissions from the Land into the Sea Yasuo Nihei 1,*, Takushi Yoshida 2, Tomoya Kataoka 1 and Riku Ogata 2 1 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science, Chiba 278-8510, Japan; [email protected] 2 Business Planning and Development Division, Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd., Tokyo 111-8648, Japan; [email protected] (T.Y.); [email protected] (R.O.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-4-7124-1501; Fax: +81-4-7123-9766 Received: 22 February 2020; Accepted: 25 March 2020; Published: 27 March 2020 Abstract: Plastic debris presents a serious hazard to marine ecosystems worldwide. In this study, we developed a method to evaluate high-resolution maps of plastic emissions from the land into the sea offshore of Japan without using mismanaged plastic waste. Plastics were divided into microplastics (MicPs) and macroplastics (MacPs), and correlations between the observed MicP concentrations in rivers and basin characteristics, such as the urban area ratio and population density, were used to evaluate nationwide MicP concentration maps. A simple water balance analysis was used to calculate the annual outflow for each 1 km mesh to obtain the final MicP emissions, and the MacP input was evaluated based on the MicP emissions and the ratio of MacP/MicP obtained according to previous studies. Concentration data revealed that the MicP concentrations and basin characteristics were significantly and positively correlated. Water balance analyses demonstrated that our methods performed well for evaluating the annual flow rate, while reducing the computational load. -

On Integrated Urban Flood Risk Management April 18-21, 2016

Public Disclosure Authorized TECHNICAL DEEP DIVE ON INTEGRATED URBAN Public Disclosure Authorized RISK MANAGEMENT SUMMARY REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized TECHNICAL DEEP DIVE (TDD) ON INTEGRATED URBAN FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT APRIL 18-21, 2016 Co-organized by the World Bank Disaster Risk Management Hub, Tokyo, and the World Bank Tokyo Development Learning Center in partnership with the government of Japan (Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism), the Urban Floods Community of Practice, and Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery This report was prepared by World Bank staff. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions: The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to the work is given. The material in this work is subject to copyright. © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / International Development Association or The World Bank 1818 -

Jr East Group Csr Report 2017

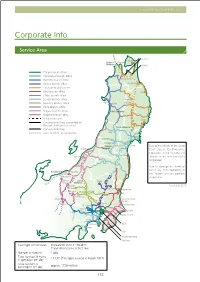

JR EAST GROUP CSR REPORT 2017 Corporate Info Service Area Aomori Ominato Hokkaido Mimmaya Shinkansen Noheji Tokyo branch office Yokohama branch office Hachioji branch office Shin-Aomori Omiya branch office Hachinohe Takasaki branch office Mito branch office Kuji Chiba branch office Sendai branch office Koma Oga Morioka branch office Akita Morioka Akita branch office Niigata branch office Akita Shinkansen Nagano branch office Shinkansen lines Sakari Conventional lines converted for through Shinkansen service Tohoku Shinkansen Conventional lines Lines of other JR companies Shinjo Onagawa Aterazawa Yamagata Yamagata Aobadori Sendai Due to the effects of the Great Niigata Shinkansen East Japan Earthquake, operations of the Yamada and Fukushima Yahiko Joban Lines are partially suspended. Due to damage by torrential rain in July 2011, operations of Hokuriku Shinkansen Naoetsu the Tadami Line are partially Joetsumyoko suspended. Minami- Joetsu Nikko Otari Shinkansen Nagano As of July 2017 Omae Karasuyama Hitachi-ota Komoro Takasaki Mito Yokokawa Shiojiri Kashima-Soccer Stadium Tatsuno Omiya Oku-Tama Kashimajingu Musashi- Choshi Kofu Itsukaichi Hachioji Narita Airport Kozu Kurihama Chiba Atami Ito Tokyo Kazusa-Kameyama Yokohama Passenger line network Shinkansen lines: 1,194.2km Conventional lines: 6,263.1km Number of stations 1,666 Total number of trains 12,227 (Timetable revised in March 2017) in operation per day Total number of approx. 17.50 million passengers per day 132 JR EAST GROUP CSR REPORT 2017 Businesses Outline of the JR East Group (as of July, 2017) Our company and our affiliated companies are engaged in transportation business, distribution and services business, real estate and hotel business, and other businesses.