Tohoku Earthquake & Tsunami Event Recap Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Urban Resilience Through Spatial Planning Following Disasters

BUILDING URBAN RESILIENCE THROUGH SPATIAL PLANNING FOLLOWING DISASTERS THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI DISSERTATION BY NADINE MÄGDEFRAU SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ENGINEERING (DR.-ING.) AT THE FACULTY OF SPATIAL PLANING OF THE TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF DORTMUND DECEMBER 2016 Front Cover: Own illustration | Photo by author (October 2015) Doctoral Committee Supervisors PROF. DR. STEFAN GREIVING Technical University of Dortmund, Germany Faculty of Spatial Planning Institute of Spatial Planning PROF. DR. MICHIO UBAURA Tohoku University Department of Architecture and Building Science Urban and Regional Planning System Lab Examiner PROF. DR. SABINE BAUMGART Technical University of Dortmund, Germany Faculty of Spatial Planning Department of Urban and Regional Planning Dissertation at the Faculty of Spatial Planning of the Technical University of Dortmund, Dortmund. BUILDING URBAN RESILIENCE THROUGH SPATIAL PLANNING FOLLOWING DISASTERS THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI DISSERTATION BY NADINE MÄGDEFRAU SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ENGINEERING (DR.-ING.) AT THE FACULTY OF SPATIAL PLANING OF THE TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF DORTMUND DECEMBER 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENT “It is complicated.” This is one of the phrases that I heard most frequently throughout my research in Tohoku Region. It referred to the reconstruction process, but can equally be applied to the endeavor of writing a dissertation. It was complicated to find an appropriate research topic. It was complicated to collect and understand the required data (mainly written in a foreign language) and to comprehend the complex processes that took and take place in Tohoku Region to recover from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. -

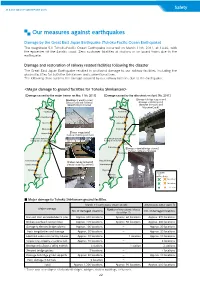

JR EAST GROUP CSR REPORT 2015 Safety

JR EAST GROUP CSR REPORT 2015 Safety Our measures against earthquakes Damage by the Great East Japan Earthquake (Tohoku-Pacific Ocean Earthquake) The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-Pacific Ocean Earthquake occurred on March 11th, 2011, at 14:46, with the epicenter off the Sanriku coast. Zero customer fatalities at stations or on board trains due to the earthquake. Damage and restoration of railway related facilities following the disaster The Great East Japan Earthquake resulted in profound damage to our railway facilities, including the ground facilities for both the Shinkansen and conventional lines. The following chart outlines the damage incurred by our railway facilities due to the earthquake. <Major damage to ground facilities for Tohoku Shinkansen> 【Damage caused by the major tremor on Mar. 11th, 2011】 【Damage caused by the aftershock on April 7th, 2011】 【Breakage of electric poles】 【Damage to bridge supports and (Between Sendai and Shinkansen breakage of electric poles】 General Rolling Stock Center) (Between Ichinoseki and Mizusawa-Esashi) Shin-Aomori Shin-Aomori Hachinohe Hachinohe Iwate-Numakunai Iwate-Numakunai Morioka Morioka Kitakami Kitakami Ichinoseki 【Track irregularity】 (Sendai Station premises) Ichinoseki Shinkansen General Shinkansen General Rolling Stock Center Rolling Stock Center Sendai Sendai Fukushima Fukushima 【Damage to elevated bridge columns】 (Between Sendai and Furukawa) Kōriyama Kōriyama Nasushiobara Nasushiobara 【Fallen ceiling material】 Utsunomiya (Sendai Station platform) Utsunomiya Oyama Oyama 【Legend】 Ōmiya Ōmiya Civil engineering Tōkyō Tōkyō Electricity 50 locations 10 locations 1 location ■ Major damage to Tohoku Shinkansen ground facilities March 11 earthquake (main shock) Aftershocks (after April 7) Major damage Number of not restored places No. of damaged locations No. -

Guideline for Extraction of Ground Motion Parameters for Scientific Hydraulic Fracturing Review Panel

Guideline for Extraction of Ground Motion Parameters for Scientific Hydraulic Fracturing Review Panel Alireza Babaie Mahani Ph.D. P.Geo. Mahan Geophysical Consulting Inc. Victoria, BC Email: [email protected] Website: www.mahangeo.com Executive Summary The Scientific Review of Hydraulic Fracturing in British Columbia (2019) provides the key findings of a scientific panel on the topic of hydraulic fracturing in British Columbia and the associated environmental risks. As indicated in the report, the panel recommends preparation of guidelines for standard calculation of earthquake magnitude and ground motion parameters. Since Babaie Mahani and Kao (2019 and 2020) have addressed the methodology for calculation of local magnitude in two publications, this report deals with standard methodologies for extraction of ground motion parameters from recorded earthquake waveforms. The guidelines include data from both types of seismic sensors that are used for induced seismicity monitoring; seismometers that record ground motion velocities and accelerometers that are designed to record strong ground accelerations at short distances. Waveforms from the November 30, 2018 induced earthquake with moment magnitude (Mw) of 4.6 that occurred in northeast British Columbia within the Montney unconventional resource play are presented for better understanding of the processing steps. Data Formats The standard format that is used to archive earthquake data is called the SEED format (Standard for the Exchange of Earthquake Data; https://ds.iris.edu/ds/nodes/dmc/data/formats/seed/). When both the time series data and metadata are archived in one file, the name full-SEED is also used. miniSEED is the stripped down version of SEED that only includes waveform data (https://ds.iris.edu/ds/nodes/dmc/data/formats/miniseed/). -

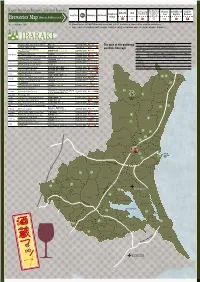

Ibaraki (PDF/6429KB)

Tax Free Shop Kanto-Shinetsu Regional Taxation Bureau Tax Free Shop Brewery available for English website shop consumption tax telephone consumption tax tour English Brochure Location No. Breweries Mainbrand & liquor tax (Wineries,Distilleries,et al.) number As of December, 2017 ※ Please refer to SAKE Brewery when you visit it, because a reservation may be necessary. ※ A product of type besides the main brand is being sometimes also produced at each brewery. ❶ Domaine MITO Corp. Izumi-cho Winery MITO Wine 029-210-2076 Shochu (C) Shochu (Continuous Distillation) Mito The type of the mainbrand ❷ MEIRI SHURUI CO.,LTD MANYUKI Shochu (S) 029-247-6111 alcoholic beverage Shochu (S) Shochu (Simple system Distillation) Isakashuzouten Limited Shochu (S) Sweet sake ❸ Partnership KAMENOTOSHI 0294-82-2006 Beer Beer, Sparkling liquor New genre(Beer-like liqueur) Hitachiota ❹ Okabe Goumeigaisha YOKAPPE Shochu (S) 0294-74-2171 ❺ Gouretsutominagashuzouten Limited Partnership Kanasagou Shochu (S) 0294-76-2007 Wine Wine, Fruit wine, Sweet fruit wine ❻ Hiyamashuzou Corporation SHOKOUSHI Wine 0294-78-0611 Whisky ❼ Asakawashuzou Corporation KURABIRAKI Shochu (S) 0295-52-0151 Liqueurs Hitachiomiya ❽ Nemotoshuzou Corporation Shochu (S) Doburoku ❾ Kiuchi Kounosu Brewery HITACHINO NEST BEER Beer 029-298-0105 Naka Other brewed liquors ❿ Kiuchi Nukata Brewery HITACHINO NEST BEER Beer 029-212-5111 ⓫ Kakuchohonten Corporation KAKUSEN Shochu (S) 0295-72-0076 Daigo ⓬ Daigo Brewery YAMIZO MORINO BEER Beer 0295-72-8888 ⓭ Kowa Inc. Hitachi Sake Brewery KOUSAI Shochu (S) -

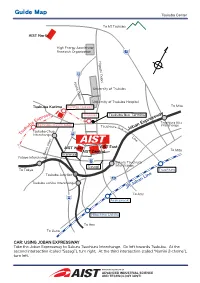

Guide Map Tsukuba AIST

Guide Map Tsukuba Center To Mt.Tsukuba AIST North High Energy Accelerator Research Organization 125 Higashi Odori 408 Nishii Odori University of Tsukuba University of Tsukuba Hospital Tsukuba Karima Kenkyu Gakuen To Mito Tsukuba Bus Terminal ess Tsukuba pr Ex a Tsuchiura Kita b Interchange u Bampaku Kinen Koen Tsuchiura k Ga u ku Joban Expressway s Tsukuba-Chuo en 408 T Interchange L in e AIST West AIST East To Mito AIST Central Sience Odori Inarimae Yatabe Interchange 354 Sakura Tsuchiura Sasagi Interchange To Tokyo Tsuchiura Tsukuba Junction 6 Tsukuba ushiku Interchange JR Joban Line To Ami 408 Arakawaoki Hitachino Ushiku To Ami To Ueno CAR: USING JOBAN EXPRESSWAY Take the Joban Expressway to Sakura Tsuchiura Interchange. Go left towards Tsukuba. At the second intersection (called “Sasagi”), turn right. At the third intersection (called “Namiki 2-chome”), turn left. Guide Map Tsukuba Center TRAIN: USING TSUKUBA EXRESS Take the express train from Akihabara (45 min) and get off at Tsukuba Station. Take exit A3. (1) Take the Kanto Tetsudo bus going to “Arakawaoki (West Entrance) via Namiki”, “South Loop-line via Tsukuba Uchu Center” or “Sakura New Town” from platform #4 at Tsukuba Bus Terminal. Get off at Namiki 2-chome. Walk for approximately 3 minutes to AIST Tsukuba Central. (2) Take a free AIST shuttle bus. Several NIMS shuttle buses go to AIST Tsukuba Central via NIMS and AIST Tsukuba East and you may take the buses at the same bus stop. Please note that the shuttle buses are small vehicles and they may not be able to carry all visitors. -

Tsunami Damage in Ports by the 2011 Off Pacific Coast of Tohoku Earthquake

Proceedings of the International Symposium on Engineering Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, March 1-4, 2012, Tokyo, Japan TSUNAMI DAMAGE IN PORTS BY THE 2011 OFF PACIFIC COAST OF TOHOKU EARTHQUAKE Takashi TOMITA1 and Gyeong-Seon YOEM2 1 Research Director, Asia-Pacific Center for Coastal Disaster Research, Port and Airport Research Institute, Yokosuka, Japan, [email protected] 2 Researcher, Asia-Pacific Center for Coastal Disaster Research, Port and Airport Research Institute, Yokosuka, Japan, [email protected] ABSTRACT: The tsunami generated by the 2011 off Pacific Coast of Tohoku Earthquake caused devastated damage in wide areas by not only inundation but also tsunami^-debris. We cannot control generation of earthquake even with state-of-arts technologies. However, we can surely mitigate possible disasters with adequate human responses. To fear tsunamis appropriately and to prepare adequate measure with local characteristics are important to preparing possible tsunamis/ Key Words: Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, port, inundation, destruction, debris, estimation, disaster mitigation, disaster prevention INTRODUCTION Japan has many experiences of tsunami disasters such as the 1896 Meiji Sanriku tsunami that caused 22,000 dead and missing. Even after improvement of coastal defense systems which have been significantly implemented since the 1960s, the 1983 Nihon-kai Chubu earthquake tsunami (the Japan Sea tsunami) killed 100 persons, and 1993 Hokkaido Nansei-oki earthquake tsunami (the Okushiri tsunami) caused 230 dead and missing including casualties by the seismic damage. In the case of Okushiri tsunami, many residents in Okushiri Island escaped to hills soon after the earthquake shock and saved their lives, because the residents had a disaster experience of the 1983 Japan Sea tsunami which hit and inundated the southern part of the island and caused two missing persons. -

Disaster Management of India

DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN INDIA DISASTER MANAGEMENT 2011 This book has been prepared under the GoI-UNDP Disaster Risk Reduction Programme (2009-2012) DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN INDIA Ministry of Home Affairs Government of India c Disaster Management in India e ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The perception about disaster and its management has undergone a change following the enactment of the Disaster Management Act, 2005. The definition of disaster is now all encompassing, which includes not only the events emanating from natural and man-made causes, but even those events which are caused by accident or negligence. There was a long felt need to capture information about all such events occurring across the sectors and efforts made to mitigate them in the country and to collate them at one place in a global perspective. This book has been an effort towards realising this thought. This book in the present format is the outcome of the in-house compilation and analysis of information relating to disasters and their management gathered from different sources (domestic as well as the UN and other such agencies). All the three Directors in the Disaster Management Division, namely Shri J.P. Misra, Shri Dev Kumar and Shri Sanjay Agarwal have contributed inputs to this Book relating to their sectors. Support extended by Prof. Santosh Kumar, Shri R.K. Mall, former faculty and Shri Arun Sahdeo from NIDM have been very valuable in preparing an overview of the book. This book would have been impossible without the active support, suggestions and inputs of Dr. J. Radhakrishnan, Assistant Country Director (DM Unit), UNDP, New Delhi and the members of the UNDP Disaster Management Team including Shri Arvind Sinha, Consultant, UNDP. -

15 to Enhance and Strengthen Port Functions and Measures for Cargo

To enhance and strengthen port functions and measures for cargo collection, taking into consideration the conditions surrounding the Port of Kawasaki in recent years, such as wide-area linkage of the three Keihin ports (Port of Kawasaki, Port of Yokohama, and Port of Tokyo), and the Port of Kawasaki's selection as a Strategic International Container Port, the City of Kawasaki revised the harbor plan for the Port of Kawasaki, which focuses on the years from 2023 to 2028, in November 2014. This plan plays an extremely important role as a guideline for development, use, and conservation of the Port of Kawasaki, based on the role of this port within the three Keihin ports, as well as demands from port-related personnel, location companies, citizens, and the government. In an aim to increase industrial competitive strength in the metropolis, and protect and develop industries, employment, and livelihood based on reinforcing the linkage among the three Keihin ports, policies for the harbor plan are being established for each function in order to realize a Port of Kawasaki that supports industrial activities and contributes to the stability and improvement of the local economy and civilian life. [Industry/logistics functions] Strengthen logistics functions by reorganizing and expanding port functions [Disaster-prevention functions] Strengthen support functions at times when a large-scale earthquake occurs [Energy functions] Maintain and support energy supply functions [Environment/interaction functions] Enhance amenity space that makes use of the characteristics of the port space 15 Port capabilities are a premise that determines the scale and layout of port facilities, and the cargo amount handled is a basic indicator that represents port capabilities. -

CORPORATE DIRECTORY (As of June 28, 2000)

CORPORATE DIRECTORY (as of June 28, 2000) JAPAN TOKYO ELECTRON KYUSHU LIMITED TOKYO ELECTRON FE LIMITED Saga Plant 30-7 Sumiyoshi-cho 2-chome TOKYO ELECTRON LIMITED 1375-41 Nishi-Shinmachi Fuchu City, Tokyo 183-8705 World Headquarters Tosu City, Saga 841-0074 Tel: 042-333-8411 TBS Broadcast Center Tel: 0942-81-1800 District Offices 3-6 Akasaka 5-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-8481 Kumamoto Plant Osaka, Kumamoto, Iwate, Tsuruoka, Sendai, Tel: 03-5561-7000 2655 Tsukure, Kikuyo-machi Aizuwakamatsu, Takasaki, Mito, Nirasaki, Toyama, Fax: 03-5561-7400 Kikuchi-gun, Kumamoto 869-1197 Kuwana, Fukuyama, Higashi-Hiroshima, Saijo, Oita, URL: http://www.tel.co.jp/tel-e/ Tel: 096-292-3111 Nagasaki, Kikuyo, Kagoshima Regional Offices Ozu Plant Fuchu Technology Center, Osaka Branch Office, 272-4 Takaono, Ozu-machi TOKYO ELECTRON DEVICE LIMITED Kyushu Branch Office, Tohoku Regional Office, Kikuchi-gun, Kumamoto 869-1232 1 Higashikata-cho, Tsuzuki-ku Yamanashi Regional Office, Central Research Tel: 096-292-1600 Yokohama City, Kanagawa 224-0045 Laboratory/Process Technology Center Koshi Plant Tel: 045-474-7000 Sales Offices 1-1 Fukuhara, Koshi-machi Sales Offices Sendai, Nagoya Kikuchi-gun, Kumamoto 861-1116 Utsunomiya, Mito, Kumagaya, Kanda, Tachikawa, Tel: 096-349-5500 Yamanashi, Matsumoto, Nagoya, Osaka, Fukuoka TOKYO ELECTRON TOHOKU LIMITED Tohoku Plant TOKYO ELECTRON MIYAGI LIMITED TOKYO ELECTRON LEASING CO., LTD. 52 Matsunagane, Iwayado 1-1 Nekohazama, Nemawari, Matsushima-machi 30-7 Sumiyoshi-cho 2-chome Esashi City, Iwate 023-1101 Miyagi-gun, Miyagi -

Ecological and Biological Studies of Ocean Rafting: Japanese Tsunami Marine Debris in North America and the Hawaiian Islands

Aquatic Invasions (2018) Volume 13, Issue 1: 1–9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2018.13.1.01 © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC Special Issue: Transoceanic Dispersal of Marine Life from Japan to North America and the Hawaiian Islands as a Result of the Japanese Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011 Introduction to Special Issue Ecological and biological studies of ocean rafting: Japanese tsunami marine debris in North America and the Hawaiian Islands James T. Carlton1,2,*, John W. Chapman3, Jonathan B. Geller4, Jessica A. Miller3, Gregory M. Ruiz5, Deborah A. Carlton2, Megan I. McCuller2, Nancy C. Treneman6, Brian P. Steves5, Ralph A. Breitenstein7, Russell Lewis8, David Bilderback9, Diane Bilderback9, Takuma Haga10 and Leslie H. Harris11 1Maritime Studies Program, Williams College-Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Connecticut 06355, USA 2Williams College, Williamstown MA 01267, USA 3Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, Hatfield Marine Science Center, 2030 SE Marine Science Drive, Newport, Oregon 97365, USA 4Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, Moss Landing, California 95039, USA 5Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Edgewater, Maryland 21037, USA 6Oregon Institute of Marine Biology, Charleston, Oregon 97420, USA 7College of Earth, Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences in Corvallis, Oregon State University, 104 CEOAS Administration Building Corvallis, OR 97331, USA 8P.O. Box 867, Ocean Park, Washington 98640, USA 93830 Beach Loop Drive SW, Bandon, Oregon 97411, USA 10National Museum of Nature and Science, -

A Review of the Seismic Hazard Zonation in National Building Codes in the Context of Eurocode 8

A REVIEW OF THE SEISMIC HAZARD ZONATION IN NATIONAL BUILDING CODES IN THE CONTEXT OF EUROCODE 8 Support to the implementation, harmonization and further development of the Eurocodes G. Solomos, A. Pinto, S. Dimova EUR 23563 EN - 2008 A REVIEW OF THE SEISMIC HAZARD ZONATION IN NATIONAL BUILDING CODES IN THE CONTEXT OF EUROCODE 8 Support to the implementation, harmonization and further development of the Eurocodes G. Solomos, A. Pinto, S. Dimova EUR 23563 EN - 2008 The mission of the JRC is to provide customer-driven scientific and technical support for the conception, development, implementation and monitoring of EU policies. As a service of the European Commission, the JRC functions as a reference centre of science and technology for the Union. Close to the policy-making process, it serves the common interest of the Member States, while being independent of special interests, whether private or national. European Commission Joint Research Centre Contact information Address: JRC, ELSA Unit, TP 480, I-21020, Ispra(VA), Italy E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: +39-0332-789989 Fax: +39-0332-789049 http://www.jrc.ec.europa.eu Legal Notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server http://europa.eu/ JRC 48352 EUR 23563 EN ISSN 1018-5593 Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities © European Communities, 2008 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Printed in Italy Executive Summary The Eurocodes are envisaged to form the basis for structural design in the European Union and they should enable engineering services to be used across borders for the design of construction works. -

Suica Pasmo Network

To Matō Kassemba Ienaka Tōbu-kanasaki Niregi Momiyama Kita-kanuma Itaga Shimo-goshiro Myōjin Imaichi Nikkō Line To Aizu-Wakamatsu To Sendai To Fukushima Jōban Line To Haranomachi Watarase Keikoku Railway Nikkō Ban-etsu-East Line Shin-kanuma Niigata Area Akagi Tanuma Tada Tōbu Nikkō Line Minami- Tōbu-nikkō Iwaki / Network Map To Chuo-Maebashi ※3 To Kōriyama Kuzū Kami- Uchigō To Murakami ★ Yashū-ōtsuka Kuniya Omochanomachi Nishikawada Esojima utsunomiya Tōhoku Line Tōbu Sano Line TsurutaKanumaFubasami Shin-fujiwara Jomo Electric Railway Yoshimizu Shin-tochigi Shimo- imaichi Shin-takatokuKosagoeTobu WorldKinugawa-onsen SquareKinugawa-kōen Yumoto ■Areas where Suica /PASMO can be used Yashū-hirakawa Mibu Tōbu Utsunomiya Line Yasuzuka Kuroiso Shibata Tōhoku Tōhoku Shinkansen imaichi Line Aizu Kinugawa Aioi Nishi-Kiryu Horigome Utsunomiya Line Shimotsuke-Ōsawa Tōbu Kinugawa Line Izumi Daiyamukō Ōkuwa Railway Yagantetsudo To Naoetsu To Niigata Omata YamamaeAshikagaAshikaga TomitaFlower Park Tōbu-utsunomiya Ueda Yaita Nozaki Nasushiobara Nishi-Shibata Nakaura Echigo TOKImeki Railway Ishibashi Suzumenomiya Nakoso Kunisada Iwajuku Shin-kiryū Kiryū Ryōmō Line Sano Iwafune Ōhirashita Tochigi Omoigawa To Naganoharakusatsuguchi ShikishimaTsukudaIwamotoNumataGokan KamimokuMinakami Shin-ōhirashita Jichi Medical Okamoto Hōshakuji Karasuyama Ujiie Utsunomiya Kamasusaka Kataoka Nishi-Nasuno Ōtsukō Sasaki To Echigo-Yuzawa Azami Sanoshi To Motegi Utsunomiya Line Line Uetsu LineTsukioka Jōmō-Kōgen ★ Shizuwa University Isohara Shibukawa Jōetsu Line Yabuzuka