Raiffeisentoday Chapter8-3 Italien

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BIKE: DOLOMITES – VENICE from the Dolomites Through the Veneto to Venice Page 1 of 4

Bicycle holiday ROAD BIKE: DOLOMITES – VENICE From the Dolomites through the Veneto to Venice Page 1 of 4 Pentaphoto DESCRIPTION Villabassa/ AUSTRIA Dobbiaco From the north east of the Dolomites, you cycle over well-known fa- Cortina mous mountain passes. Lake Misurina, the “Drei Zinnen” (Three Peaks) d‘Ampezzo and the Olympic town of Cortina d’Ampezzo are only some of the high- Auronzo lights you will see along the way. The tour takes you on to Bassano del di Cadore Grappa where the land starts to level out. From here you slowly cycle downwards into the valley. After a short detour to Asolo, the town of a Belluno hundred horizons, you will cycle along the wine road from Valdobbi- adene to Vittorio Veneto. The fashionable town of Treviso waits upon Feltre your arrival to greet you. Following the path along the river Sile, you cycle on towards the final destination of the bike tour through Northern ITALY Italy until you reach Venice. Treviso Bassano del CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ROUTE Grappa Quarto d‘Altino TSF It’s a sporty-racing bike tour for cyclists with a good physical prepara- Lido di Jesolo VCE tion. The passes of the Dolomites ask for preparation, because there are Venice/ a few longer ascents to climb (most aside of the big travelled streets – Mestre except during high season July / August). The second half of the week is going to be easier; you reach the flatter landscape of Venice. self-guided tour road bike DIFFICULTY: medium DURATION: 8 days / 7 nights DISTANCE: approx. 495 – 575 km Alps 2 Adria Touristik OG Bahnhofplatz 2, 9020 Klagenfurt am Wörthersee • Carinthia, Austria • +43 677 62642760 • [email protected] • www.alps2adria.info ROAD BIKE: DOLOMITES – VENICE Page 2 of 4 A DAY BY DAY ACCOUNT OF THE ROUTE Day 1: Arrival Individual arrival at the starting hotel in the Upper Puster Valley (Villabassa / Dobbiaco). -

The Dolomites a Guided Walking Adventure

ITALY The Dolomites A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 16 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 18 Information & Policies ............................................................ 23 Italy at a Glance ..................................................................... 25 Packing List ........................................................................... 30 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2017 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our optional Flight + Tour Combo and Venice PostPost----TourTour Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. Overview Dramatic pinnacles of white rock, flower-filled meadows, fir forests, and picturesque villages are all part of the renowned Italian Dolomites, protected in national and regional parks and recently recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The luminous limestone range is the result of geological transformation from ancient sea floor to mountaintop. The region is a landscape of grassy balconies perched above Alpine lakes, and Tyrolean hamlets nestled in lush valleys, crisscrossed by countless hiking and walking trails connecting villages, Alpine refuges, and cable cars. The Dolomites form the frontier between Germanic Northern Europe and the Latin South. -

Biathlon Centre Antholz/Anterselva Welcome to South Tyrol!

50 th EFNS European Forester‘s competition in Nordic Skiing 28.01. - 03.02.2018 Welcome to South Tyrol! Biathlon centre Antholz/Anterselva Südtirol Arena Alto Adige Welcome to Antholz, Welcome to South Tyrol! 1 Dear Sport Friends, on behalf of the South Tyrolian Forestry Association, I would like to welcome you to the “European Forester's Competition in Nordic Skiing” in South Tyrol. This year, the EFNS championship takes place for the 50th time. A very special anniversary – and it is a pleasure to host this event. The location Antholz/Anterselva, where the Biathlon World Cup takes place annually, is famous all over Europe. It is a wonderful sporting area in the middle of forests in between the Lake of Antholz and the stunning mountains of the Rieserferner Group. It’s already the third time that the South Tyrolian Forestry Association hosts the “European Forester's Competition in Nordic Skiing”. The competition has already been held in 1984 in Kastelruth/Castelrotto and 1992 in Toblach/Dobbiaco. 26 years later, it returns for its 50th anniversary. The organising committee led by our motivated chair Heinrich Schwingshackl has been working intensively for over 2 years to organize interesting competitions and an attractive frame programme. A very special highlight is the Jubilee Run “50 Years EFNS”: Every cross-country enthusiast can run the popular Tour de Ski course from Cortina to Toblach/Dobbiaco without timekeeping. EFNS is not only about sports competitions but also about friendship without borders. It is remarkable that so many participants with different jobs in the wood and forestry sector of over 20 European Countries come together. -

Referenzliste

Referenzliste Objekt Ort Bauherr Schulen und Kindergärten: Landwirtschaftsschule “Fürstenburg” Burgeis Autonome Provinz Bozen Italienischer Kindergarten Bruneck Gemeinde Bruneck Landwirtschaftsschule AUER Auer Autonome Provinz Bozen Hotelfachschule “Kaiserhof” Meran Autonome Provinz Bozen Mittelschule Naturns Gemeinde Naturns Volksschule und Kindergarten St. Martin Passeier Gemeinde St.Martin in Passeier Gymnasium Schlanders Autonome Provinz Bozen Volksschule und Kindergarten St. Nikolaus Ulten Gemeinde Ulten Grundschule Pfalzen Gemeinde Pfalzen Mittelschule Meusburger Bruneck Stadtgemeinde Bruneck Schule St.Andrä Brixen Stadtgemeinde Brixen Grundschule J.Bachlechner Bruneck Stadtgemeinde Bruneck Fachschule für Land- und Hauswirtschaft Bruneck Autonome Provinz Bozen Dietenheim Kindergarten Pfalzen Gemeinde Pfalzen Alters- und Pflegeheime: Auer Auer Geneinde Auer Schlanders Schlanders Gemeinde Schlanders Latsch Latsch Gemeinde Latsch „Sonnenberg“ Eppan Eppan Schwestern - Deutscher Orden Leifers Leifers Sozialsprengel Leifers Meran Meran Stadtgemeinde Meran St. Pankraz St.Pankraz Gemeinde St. Pankraz Tscherms Tscherms Gemeinde Tscherms „Eden“ -Meran Meran Sozialsprengel Eden Wohn – und Pflegeheim Olang Olang Wohn- und Pflegeheime Mittleres Pustertal Psychiatrisches Reha Zentrum mit psychiatrischem Bozen Provinz Bozen Wohnheim Bozen KRANKENHÄUSER – SANITÄTSSPRENGEL Krankenhaus Bozen: Bozen Autonome Provinz Bozen verschiedene Abteilungen, Kälteverbundanlage, Wäscherei, Abteilung Infektionskrankheiten, Hämatologie, Kühlung Krankenzimmer Umbau -

Kondomautomaten in Südtirol Seite 1

Kondomautomaten in Südtirol Art der Einrichtung Name Straße PLZ Ort Pub Badia Pedraces 53 39036 Abtei Pizzeria Nagler Pedraces 31 39036 Abtei Pizzeria Kreuzwirt St. Jakob 74 39030 Ahrntal Pub Hexenkessel Seinhaus 109 c 39030 Ahrntal Jausenstation Ledohousnalm Weissenbach 58 39030 Ahrntal Hotel Ahrntaler Alpenhof Luttach 37 39030 Ahrntal / Luttach Restaurant Almdi Maurlechnfeld 2 39030 Ahrntal / Luttach Gasthaus Steinhauswirt Steinhaus 97 39030 Ahrntal / Steinhaus Cafe Steinhaus Ahrntalerstraße 63 39030 Ahrntal / Steinhaus Skihaus Sporting KG Enzschachen 109 D 39030 Ahrntal / Steinhaus Bar Sportbar Aicha 67 39040 Aicha Braugarten Forst Vinschgauerstraße 9 39022 Algund Restaurant Römerkeller Via Mercato 12 39022 Algund Gasthaus Zum Hirschen Eweingartnerstraße 5 39022 Algund Camping Claudia Augusta Marktgasse 14 39022 Algund Tankstelle OMV Superstrada Mebo 39022 Algund Restaurant Stamserhof Sonnenstraße 2 39010 Andrian Bar Tennisbar Sportzone 125 39030 Antholz/Mittertal Club Road Grill Schwarzenbachstraße 4 39040 Auer Pub Zum Kalten Keller St. Gertraud 4 39040 Barbian Pizzeria Friedburg Landstraße 49 / Kollmann 39040 Barbian Baita El Zirmo Castelir 6 - Ski Area 38037 Bellamonte Bistro Karo Nationalstraße 53 39050 Blumau Pub Bulldog Dalmatienstraße 87 39100 Bozen Bar Seeberger Sill 11 39100 Bozen Bar Haidy Rittnerstraße 33 39100 Bozen Tankstelle IP Piazza Verdi 39100 Bozen Bar Restaurant Cascade Kampillerstraße 11 39100 Bozen Bar Messe Messeplatz 1 39100 Bozen Bar 8 ½ Piazza Mazzini 11 39100 Bozen Bar Nadamas Piazza delle Erbe 43/44 39100 -

Kiens Chienes Ausflugsziele

D I E 8 GROSSE DOLOMITENFAHRT Inoltre vogliamo presentarVi diverse escursioni raccomandabili che potrete ➟ 220 km – Tagesfahrt: Kiens, Bruneck, Toblach (1200 m), fare senza difficoltà con la Vostra macchina o con l’aiuto dei nostri uffici Höhlensteintal, Misurinasee (1755 m), Tre Croci-Pass (1809 m), viaggi. Cortina (1224 m), Falzaregopass (2117 m), Arabba, Pordoijoch, Sellapass (2240 m), St. Ulrich im Grödnertal, Klausen, Brixen und zurück oder nach Sellapass über Cavalese, Auer, Bozen, Klausen, 1 LAGO DI BRAIES Kiens Brixen und zurück. ➟ viaggio di mezza giornata – 75 km passando per Brunico attraverso la Val Pusteria fino a Monguelfo, la Valle di Braies, il lago di Braies Chienes 9 SÜDTIROLER WEINSTRASSE – KALTERER SEE (potrete ammirare la bellezza di questo romantico lago di montagna, ➟ Tagesfahrt über Brixen, Bozen, Weinstraße, Eppan, Kaltern che si trova ai piedi della Croda del Becco, facendo il giro). (Kellereibesuch mit Weinverkostung, Weinmuseum), Kalterer See (Bademöglichkeit), Auer, Bozen und zurück. 2 VALLE AURINA PUSTERTAL - VAL PUSTERIA VAL - PUSTERTAL ➟ viaggio di mezza giornata – Brunico, Valle Aurina (eventuale visita 10 JAUFENPASS MERAN delle cascate di Rio di Riva (Molini di Tures) e del castello di Campo ➟ Tagesfahrt – 210 km. Ab Kiens, Sterzing, Jaufenpass (2094 m), Tures), scegliere lo stesso percorso per il ritorno. 9 SOUTH TYROLEAN WINE STREET – LAKE OF KALTERN Passeiertal (St. Leonhard – Geburtshaus von Andreas Hofer, dem ➟ day tour across Brixen, Bozen, Wine street, Eppan, Kaltern (visit to Südtiroler Freiheitshelden von 1809), Meran, Bozen, Klausen (Kloster REFERENCES FOR 3 the winery with wine tasting, wine museum), lake of Kaltern (bathing Säben, Altstadt, Loretoschatz), Brixen und zurück. BRUNICO EMPFEHLENSWERTE ➟ strada attraverso la media montagna per Vandoies – viaggio di EXCURSION facilities), Auer, Bozen and back to Kiens. -

Linea 310 Bressanone – Vipiteno

BUS BRIXEN - STERZING 15.12.2019-12.12.2020 310 BUS BRESSANONE - VIPITENO TÄGLICHX X S X X X X X X X X A Brixen, Bahnhof ab 5.50 6.35 7.40 8.10 9.10 10.10 11.10 12.10 13.16 14.10 15.10 16.10 17.10 18.10 19.10 22.17 p. Bressanone, Stazione Brixen, Busbahnhof 5.53 6.38 7.43 8.13 9.13 10.13 11.13 12.13 13.19 14.13 15.13 16.13 17.13 18.13 19.13 22.23 Bressanone, Autostaz. Brixen, Krankenhaus 5.56 6.41 7.46 8.16 9.16 10.16 11.16 12.16 13.22 14.16 15.16 16.16 17.16 18.16 19.16 22.26 Bressanone, Ospedale Vahrn, Goldenes Lamm 6.00 6.46 7.51 8.21 9.21 10.21 11.21 12.21 13.27 14.21 15.21 16.21 17.21 18.21 19.21 22.31 Varna, Goldenes Lamm Aicha, Kirche 6.52 8.27 9.27 10.27 11.27 12.27 13.33 14.27 15.27 16.27 17.27 18.27 19.27 Aica, Chiesa Franzensfeste, Bahnhof 6.07 6.57 7.58 8.32 9.32 10.32 11.32 12.32 13.38 14.32 15.32 16.32 17.32 18.32 19.32 22.38 Fortezza, Stazione Mittewald 6.12 7.02 8.03 8.37 9.37 10.37 11.37 12.37 13.43 14.37 15.37 16.37 17.37 18.37 19.37 Mezzaselva Grasstein 6.15 7.05 8.06 8.40 9.40 10.40 11.40 12.40 13.46 14.40 15.40 16.40 17.40 18.40 19.40 Le Cave Mauls 6.19 7.10 8.11 8.45 9.45 10.45 11.45 12.45 13.51 14.45 15.45 16.45 17.45 18.45 19.45 Mules Freienfeld 6.24 7.16 8.17 8.51 9.51 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.57 14.51 15.51 16.51 17.51 18.51 19.51 Campo di Trens Bahnhof Sterzing 6.29 7.21 8.22 8.56 9.56 10.56 11.56 12.56 14.02 14.56 15.56 16.56 17.56 18.56 19.56 Stazione di Vipiteno Sterzing, Nordpark an 6.32 7.24 8.25 8.59 9.59 10.59 11.59 12.59 14.05 14.59 15.59 16.59 17.59 18.59 19.59 a. -

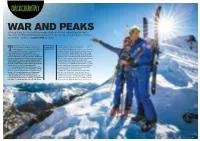

Views, Skiing Doesn’T Get Valley

BACKCOUNTRY WAR AND PEAKS Snaking along the Austro-Italian border, taking in wild and remote front line battle sites from the First World War, the Grande Circolo ski tour is made for backcountry – and history – lovers, as Louise Hall discovers he Dolomites may be known for dreamy views, Skiing doesn’t get valley. The jagged limestone peaks glow pale pink around us luscious lunches and the Dolomiti Superski, the any more wild and in the early morning light, and there’s silence but for the world’s biggest ski area with more than 1200km of unspoilt than this occasional bursts of birdsong. Skis and skins on, as we wind Tcorduroy, but it has a quieter and altogether less through farming hamlets and zig-zag across powder-covered boastful side that’s made for backcountry lovers. meadows, it’s hard to imagine that this area was the setting Among the region’s lesser known tours is the Grande for some of the most bloody of front line battles in the First Circolo, a demanding six-day route that snakes 126km along World War, where 160,000 Austrian and Italians were killed. the Austro-Italian border from Sexten in Austria to Sterzing Memories still reverberate around these hills; only in the past in Italy. I’m lucky to be part of a group of international ski 50 years has the district found peace and prospered. writers and photographers hosted by Sud Tirol and Salewa, We speed-carve through pine woods on the only corduroy the locally founded outdoor clothing brand. They’re putting we ski all week, to Vierschach train station where, as we prep us in the care of seasoned local mountain guides. -

Recapiti Degli Uffici Di Polizia Competenti in Materia

ALLOGGIATIWEB - COMUNI DELLA PROVINCIA DI BOLZANO - COMPETENZA TERRITORIALE ALLOGGIATIWEB - GEMEINDEN DER PROVINZ BOZEN - ÖRTLICHE ZUSTÄNDIGKEIT RECAPITI DEGLI UFFICI DI POLIZIA COMPETENTI ANSCHRIFTEN DER ZUSTÄNDIGEN POLIZEILICHEN ABTEILUNGEN IN MATERIA "ALLOGGIATIWEB" FÜR "ALLOGGIATIWEB" INFO POINT INFO POINT Questura di Bolzano Quästur Bozen Ufficio per le relazioni con il pubblico - URP Amt für die Beziehungen zur Öffentlichkeit - ABO Largo Giovanni Palatucci n. 1 Giovanni Palatucci Platz nr. 1 39100 Bolzano 39100 Bozen (BZ) Orario di apertura al pubblico: Lu-Ven 08.30-13.00 + Gio 15.00-17.00 Öffnungszeiten: Mon.-Fr. : 08.30 - 13.00 + Donn. 15.00-17.00 Tel.: 0471 947643 Tel.: 0471 947643 Questura di Bolzano Quästur Bozen P.A.S.I. - Affari Generali e Segreteria P.A.S.I (Verw.Pol.) - Allgemeine Angelegenheiten und Sekretariat Largo Giovanni Palatucci n. 1 Giovanni Palatucci Platz nr. 1 39100 Bolzano (BZ) 39100 Bozen (BZ) Orario di apertura al pubblico: Lu-Ven 08.30-13.00 Öffnungszeiten: Mon.-Fr. : 08.30 - 13.00 Tel.: 0471 947611 Tel.: 0471 947611 Pec: [email protected] Pec: [email protected] Commissariato di P. S. di Merano Polizeikommissariat Meran Polizia Amministrativa Verwaltungspolizei Piazza del Grano 1 Kornplatz 1 39012 Merano (BZ) 39012 Meran (BZ) Orario di apertura al pubblico: Lu-Ven 08.30-13.00 Öffnungszeiten: Mon.-Fr. : 08.30 - 13.00 Tel.: 0473 273511 Tel 0473 273511 Pec: [email protected] Pec: [email protected] Commissariato di P. S. di Bressanone Polizeikommissariat Brixen Polizia Amministrativa Verwaltungspolizei Via Vittorio Veneto 13 Vittorio Veneto Straße 13 39042 Bressanone (BZ) 39042 Brixen (BZ) Orario di apertura al pubblico: Lu-Ven 08.30-13.00 Öffnungszeiten: Mon.-Fr. -

3. Zugang Zu Krankenhausaufenthalten

Beziehungen zu den Bürgern 757 ________________________________________________________________________________ 3. ZUGANG ZU KRANKENHAUSAUFENTHALTEN 3.1. Zugang zu den Krankenhausdiensten 3.1.1. Parkmöglichkeit In allen Krankenhäusern der Provinz waren innerhalb und außerhalb des Krankenhausgeländes Parkplätze für Patienten und Besucher vorhanden; in den meisten Landeskrankenhäusern reichten sie jedoch für das Einzugsgebiet nicht aus (außer in Meran und Brixen). Tabelle 1: Verfügbare kostenlose Parkplätze, Parkplätze gegen Parkgebühr, reservierte und freie Parkplätze innerhalb und außerhalb des Krankenhausgeländes - Jahr 2003 ANZ. PARKPLÄTZE KH PARKPLÄTZE Innerh. KH- Außerh.KH- Gelände Gelände Bozen Gegen Parkgebühr* 460 € 0,50/h für die ersten beiden Std; € 0,25/h für alle weiteren Std. Kostenlos 30 Für verschiedenen Bedarf, vom Pförtnerdienst verwaltet: z.B. Abholen von Patienten, Blut-/Prothesentransporte) Kostenlos und reserviert für: - Invaliden 8 - Patienten mit besonderem klinischem Bedarf 12 - Familienangehörige von Patienten mit Versorgungsbedarf ** - Gastärzte ** Meran Gegen Parkgebühr - 160 (Tappeiner) € 0,50/h (7.00-20.00); € 1 von 20.00 bis 7.00 Uhr Kostenlos und reserviert für: - Patienten mit besonderem klinischem Bedarf - ** - Gastärzte (Sprengelkoordinatoren) - 6 - Eingelieferte Patienten ** Meran Kostenlos 25 160* (Laurin) Meran Gegen Parkgebühr - 12 (Böhler) Kostenlos und reserviert für: Behinderte 6 - Schlanders Kostenlos * 24 84 Kostenlos und reserviert für: - Invaliden 4 - Gastärzte 1 Brixen Kostenlos 50 50 Sterzing -

Holiday Guide

PUSTERTAL | VAL PUSTERIA Holiday Guide Ein großer Dank gilt den Grundbesitzern für die INHALTSVERZEICHNIS | INDICE | INDEX Bereitstellung der Wege und Wälder. Wir bitten die Besucher um respektvollen Umgang. 6 HIGHLIGHTS Ringraziamo i proprietari per la disposizione dei sentieri e delle foreste. Chiediamo i ALMEN 16 visitatori di rispettare la natura. Malghe | Alpine Huts BERGGASTHÄUSER UND HOFSCHÄNKEN 28 Thanks to the landowners for the supply of Alberghi alpini e Agriturismi | Alpine Inns paths and forests. We ask the visitors WANDERTIPPS for a respectful handling. 29 Consigli per escursioni | Hiking tipps ALMEN IN DER UMGEBUNG 55 Malghe nei dintorni | Alpine cottages in the surroundings SCHUTZHÜTTEN 56 Rifugi alpini | Alpine huts AUFSTIEGSANLAGEN 58 Impianti di risalita | Cable cars TOURENVORSCHLÄGE MOUNTAINBIKE 60 Proposte per gite in mountainbike | Recommended mountain bike tours FÜR BIKER 68 Per ciclisti | For cyclists HUNDEINFOS 70 Info cani | Dog info INFOS 74 Informazioni | Information GESCHÄFTE 86 Negozi | Shops RESTAURANTS, BARS & CAFÉS 88 Ristoranti, bar e café | Restaurants, bars and café MUSEEN 93 Musei | Museums ZEICHENERKLÄRUNG Der Umwelt zuliebe! 102 Per il bene dell‘ambiente! Legenda | Legend For the sake of the enviroment! Impressum | Imprint: Tourismusverein Antholzertal | Ass. Turistica Valle Anterselva | Tourist Info Antholzertal Herausgeber: Tourismusverein Antholzertal 39030 Rasen/Antholz | Rasun/Anterselva . Südtirol | Alto Adige . Italy Grafische Gestaltung: Nadia Huber, Sand in Taufers & Andrea Maurer, Olang -

The Südtirol Highlights 2014

The Südtirol Highlights 2014 Biathlon World Cup Anterselva/Antholz UDFHF\FOLQJFRPPXQLW\2Q0D\WKHOHJ - MD]]PXVLFSHUIRUPHGE\LQWHUQDWLRQDOO\DFFODLPHG 16th to 19th of January 2014 HQGDU\*LURGp,WDOLDUHWXUQVWR6RXWK7\URO6WDUWLQJ PXVLFLDQVLQYDULRXVYHQXHVLQIRXURI6RXWK7\UROpV Anterselva has become one of the international RQ0D\LQ3RQWHGL/HJQRWKHURXWHOHDGVRYHU PDMRUWRZQV7KHPRVWYDULHGFRQFHUWVFRPSULVLQJD sport and biathlon world´s venues most steeped in WKH3DVVR6WHOYLR7KHSDWKFRQWLQXHVWKURXJKWKH mixture of the traditional and the modern will take WUDGLWLRQZLWKDKLVWRU\RIKRVWLQJZRUOGFXSUDFHV 9DO0DUWHOOR0DUWHOOWDOYDOOH\ SODFHLQWKHUHÞQHGDWPRVSKHUHRI6RXWK7\UROpV DQGFKDPSLRQVKLSVJRLQJEDFNRYHU\HDUV www.gazzetta.it castles and manor houses, though also in town www.biathlon-antholz.it/en/ VWUHHWVDQGVTXDUHVIDYRXUHGE\WKHEDOP\ODWH Bolzano Festival Bozen spring climate. Bolzano/Bozen Wine Exhibition “Bozner Summer 2014 ZZZVXHGWLUROMD]]IHVWLYDOFRP Weinkost” 7KH%RO]DQR)HVWLYDO%R]HQKDVFRPHWRUHSUHVHQW 12th to 16th of March 2014 one of the most multi-farious and interesting “Maratona dles Dolomites” Road Bike Race, 7KHHYHQWWRRNSODFHIRUWKHÞUVWWLPHLQDVD HYHQWVRIWKHVXPPHUpVFXOWXUDOODQGVFDSH3URPLV Alta Badia “wine market” to pro-vide producers and prospec- LQJ\RXQJWDOHQWVDUHJLYHQWKHRSSRUWXQLW\IRU 6th of July 2014 WLYHEX\HUVZLWKWKHRSSRUWXQLW\WRPHHWWDVWH encounters and exchanges with well established The Maratona dles Dolomites is taking place on FRPSDUHZLQHVDQGPDNHGHDOVZKLOHWRGD\LWKDV artists. 6XQGD\DPVWDUWLQJDW/D9LOOD6WHUQLQ$OWD evolved into the “Bozner Weinkost”. The venue