Thousand-Armed Kannon a Mystery Or a Problem?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-08-17 Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography Ereshefsky, Joshua Ian Ereshefsky, J. I. (2020). Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112477 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography by Joshua Ian Ereshefsky A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA AUGUST, 2020 © Joshua Ian Ereshefsky 2020 i ABSTRACT Buddhists, across different schools and regions, traditionally posited a similar world model—one that is flat and centered by giant Mount Meru. This world model is chiefly featured in Vasubandhu’s fourth century CE text, the Abhidharmakośabhāṣyam. In 1552, Christian missionary Francis Xavier introduced European spherical-world cosmography to Japan, precipitating what this thesis terms the Buddhist -

Symbolism of the Buddhist Stūpa

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Gregory Schopen Roger Jackson Indiana University Fairfield University Bloomington, Indiana, USA Fairfield, Connecticut, USA EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Bardxvell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfteld, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Bruce Cameron Hall College of William and Mary Williamsburg, Virginia, USA Volume 9 1986 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. Signs, Memory and History: A Tantric Buddhist Theory of Scriptural Transmission, by Janet Gyatso 7 2. Symbolism of the Buddhist Stupa, by Gerard Fussman 37 3. The Identification of dGa' rab rdo rje, by A. W. Hanson-Barber 5 5 4. An Approach to Dogen's Dialectical Thinking and Method of Instantiation, by Shohei Ichimura 65 5. A Report on Religious Activity in Central Tibet, October, 1985, by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. and Cyrus Stearns 101 6. A Study of the Earliest Garbha Vidhi of the Shingon Sect, by Dale Allen Todaro 109 7. On the Sources for Sa skya Panclita's Notes on the "bSam yas Debate," by Leonard W.J. van der Kuijp 147 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. The Bodymind Experience in Japanese Buddhism: A Phenomenological Study ofKukai and Dogen, by D. Shaner (William Waldron) 155 2. A Catalogue of the s Tog Palace Kanjur, by Tadeusz Skorupski (Bruce Cameron Hall) 156 3. Early Buddhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study of the Founders' Authority, the Community, and the Discipline, by Chai-Shin Yu (Vijitha Rajapakse) 162 4. -

He Noble Path

HE NOBLE PATH THE NOBLE PATH TREASURES OF BUDDHISM AT THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY AND GALLERY OF ORIENTAL ART DUBLIN, IRELAND MARCH 1991 Published by the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. 1991 ISBN:0 9517380 0 3 Printed in Ireland by The Criterion Press Photographic Credits: Pieterse Davison International Ltd: Cat. Nos. 5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 36, 37, 43 (cover), 46, 50, 54, 58, 59, 63, 64, 65, 70, 72, 75, 78. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland: Cat. Nos. 1, 2 (cover), 52, 81, 83. Front cover reproduced by kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland © Back cover reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library © Copyright © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. Chester Beatty Library 10002780 10002780 Contents Introduction Page 1-3 Buddhism in Burma and Thailand Essay 4 Burma Cat. Nos. 1-14 Cases A B C D 5 - 11 Thailand Cat. Nos. 15 - 18 Case E 12 - 14 Buddhism in China Essay 15 China Cat. Nos. 19-27 Cases F G H I 16 - 19 Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia Essay 20 Tibet Cat. Nos. 28 - 57 Cases J K L 21 - 30 Mongolia Cat. No. 58 Case L 30 Buddhism in Japan Essay 31 Japan Cat. Nos. 59 - 79 Cases M N O P Q 32 - 39 India Cat. Nos. 80 - 83 Case R 40 Glossary 41 - 48 Suggestions for Further Reading 49 Map 50 ■ '-ie?;- ' . , ^ . h ':'m' ':4^n *r-,:«.ria-,'.:: M.,, i Acknowledgments Much credit for this exhibition goes to the Far Eastern and Japanese Curators at the Chester Beatty Library, who selected the exhibits and collaborated in the design and mounting of the exhibition, and who wrote the text and entries for the catalogue. -

Vasubandhu's) Commentary on His "Twenty Stanzas" with Appended Glossary of Technical Terms

AN INTRODUCTION AND TRANSLATION OF VINITADEVA'S EXPLANATION OF THE FIRST TEN VERSES OF (VASUBANDHU'S) COMMENTARY ON HIS "TWENTY STANZAS" WITH APPENDED GLOSSARY OF TECHNICAL TERMS Gregory Alexander Hillis Palo Alto, California B.A., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1979 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 1993 ABSTRACT In this thesis I argue that Vasubandhu categorically rejects the position that objects exist external to the mind. To support this interpretation, I engage in a close reading of Vasubandhu's Twenty Stanzas (Vif!lsatika, nyi shu pa), his autocommentary (vif!lsatika- vrtti, nyi shu pa'i 'grel pa), and Vinrtadeva's sub-commentary (prakaraiJa-vif!liaka-f'ika, rab tu byed pa nyi shu pa' i 'grel bshad). I endeavor to show how unambiguous statements in Vasubandhu's root text and autocommentary refuting the existence of external objects are further supported by Vinitadeva's explanantion. I examine two major streams of recent non-traditional scholarship on this topic, one that interprets Vasubandhu to be a realist, and one that interprets him to be an idealist. I argue strenuously against the former position, citing what I consider to be the questionable methodology of reading the thought of later thinkers such as Dignaga and Dharmak:Irti into the works of Vasubandhu, and argue in favor of the latter position with the stipulation that Vasubandhu does accept a plurality of separate minds, and he does not assert the existence of an Absolute Mind. -

Buddhist Backgrounds of the Burmese Revolution Buddhist Backgrounds Ofthe Burmese Revolution

BUDDHIST BACKGROUNDS OF THE BURMESE REVOLUTION BUDDHIST BACKGROUNDS OFTHE BURMESE REVOLUTION by E. SARKISYANZ PH.D. apl. Professor Freiburg University PREFACE BY DR. PAUL MUS Professor at the College de France and Yale University • Springer-Science+Business Media, B.Y. I965 Dedicated to the memory 01 my unlorgettable teacher ARNOLD BERGSTRAESSER ISBN 978-94-017-5830-7 ISBN 978-94-017-6283-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-017-6283-0 Copyright I965 by Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form Originally published by Martinus Nijhoff in 1965. Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover 1st edition 1965 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by PAUL Mus. VII Foreword ..... XXIII Abbreviations . XXVII I. The Buddhist tradition of Burma's history . I 11. Buddhist traditions about a perfect society, its decline and the origin of the state . .. 10 III. Republican institutions in pre-Buddhist India and in the Buddhist order. .. 17 IV. The Buddhist welfare state of Ashoka. .. 26 v. Survival of Ashokan social and political traditions in Theravada kingship . .. 33 VI. On the problem of social ethics of Theravada Buddhism 37 VII. Emergence of the Bodhisattva ideal of kingship in Theravada Buddhism . .. 43 VIII. Pre-Buddhist fertility elements of the charisma of Burmese kingship . .. 49 IX. Economic implications of the Buddhist ideal of kingship 54 x. The Bodhisattva ideal of Burmese kingship . .. 59 XI. Kamma and Buddhist merit-causality as rationale for medieval Burma's social order . .. 68 XII. Buddhist ethics against the pragmatism of power under the Burmese kings. -

Under Memberships

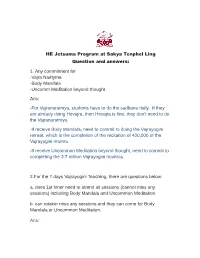

HE Jetsuma Program at Sakya Tenphel Ling Question and answers: 1. Any commitment for -Vajra Nairtyma -Body Mandala -Uncomm Meditation beyond thought Ans: -For Vajranaratmya, students have to do the sadhana daily. If they are already doing Hevajra, then Hevajra is fine, they don’t need to do the Vajranaratmya. -If receive Body Mandala, need to commit to doing the Vajrayogini retreat, which is the completion of the recitation of 400,000 of the Vajrayogini mantra. -If receive Uncommon Meditation beyond thought, need to commit to completing the 3.7 million Vajrayogini mantras. 2.For the 7 days Vajrayogini Teaching, there are questions below: a. does 1st timer need to attend all sessions (cannot miss any sessions) including Body Mandala and Uncommon Meditation. b. can retaker miss any sessions.and they can come for Body Mandala or Uncommon Meditation. Ans: a. Students who want to receive the proper transmission should attend all the sessions. However, if they don’t wish to receive the commitments of retreat and mantra accumulation (3.7 million), as is required if receive the body mandala and uncommon meditation beyond thought, they can skip those relevant sessions. b. For old timers who received the entire set before, it is their choice. However, Jetsun Kushok thinks it is beneficial to receive the teachings in its entirety without selectively choosing and skipping. 3.a For those new ones who.has taken 2 days Vajra Nairatyma empowerment, can they continue to take Vajrayogini Chin Lab and then go to the 7 days teaching? b. For those who.have taken 2 days Hevajra cause empowerment, they can come for Vajra Nairatyma empowerment and no need be one of the 25 new takers. -

Shankara: a Hindu Revivalist Or a Crypto-Buddhist?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 12-4-2006 Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist? Kencho Tenzin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tenzin, Kencho, "Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHANKARA: A HINDU REVIVALIST OR A CRYPTO BUDDHIST? by KENCHO TENZIN Under The Direction of Kathryn McClymond ABSTRACT Shankara, the great Indian thinker, was known as the accurate expounder of the Upanishads. He is seen as a towering figure in the history of Indian philosophy and is credited with restoring the teachings of the Vedas to their pristine form. However, there are others who do not see such contributions from Shankara. They criticize his philosophy by calling it “crypto-Buddhism.” It is his unique philosophy of Advaita Vedanta that puts him at odds with other Hindu orthodox schools. Ironically, he is also criticized by Buddhists as a “born enemy of Buddhism” due to his relentless attacks on their tradition. This thesis, therefore, probes the question of how Shankara should best be regarded, “a Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?” To address this question, this thesis reviews the historical setting for Shakara’s work, the state of Indian philosophy as a dynamic conversation involving Hindu and Buddhist thinkers, and finally Shankara’s intellectual genealogy. -

Key Words Key Quotes Key Concepts

WJEC A Level R.S. Unit 3D Buddhism Knowledge Organiser: Theme 2B Religion and society - responses to the challenges of science Key concepts • Buddhism rejects any form of blind faith – what is • The realms and beings within them are described in detail in various • From one perspective, Buddhism is closely aligned with science: the required is akaravati saddha (confidence based on traditions e.g. Hot Ashes Hell, 31 planes of existence in the universe divided Japanese Buddhist philosopher Inoue Enryo stated that Buddhism was reason and experience). into three realms, Mount Meru, the King of the devas, Sakra who lives on the scientific and based on fact; Huxley in the 19th century argued that the law of karma was an observable law of the universe because it was • Blindly clinging to views rather than fully grasping summit of Mount Meru in Tavatimsa one of the Buddhist heavens. entirely based on causation. the dhamma is likened to the wrong grasping of the • HH the Dalai Lama has assessed science to be of great importance in water-snake which will lead it to bite a person; wrong Tibetan Buddhism: viewing the moon through a telescope as young boy • The Dalai Lama argues Buddhism does not reify – make what is abstract grasping of the dhamma can only be countered made him begin to doubt Buddhist cosmology as found in the Abhidhamma such as God ‘material’ – and is thus more aligned with science than through close questioning of the Buddha and of Pitaka. many religions. experienced monks. • In 2000, he introduced modern science education –psychology, physics and • Sunyata, anicca, and anatta are compatible with modern science such as • In the Kalama Sutta, the Buddha teaches the Kalamas astronomy – into the Tibetan monastic curriculum; he endorsed the use of quantum physics and new discoveries about how the mind works. -

The Sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist Texts

Nepalese Culture Vol. XIII : 77-94, 2019 Central Department of NeHCA, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal The sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist texts Dr. Poonam R L Rana Abstract Mahakala is the God of Time, Maya, Creation, Destruction and Power. He is affiliated with Lord Shiva. His abode is the cremation grounds and has four arms and three eyes, sitting on five corpse. He holds trident, drum, sword and hammer. He rubs ashes from the cremation ground. He is surrounded by vultures and jackals. His consort is Kali. Both together personify time and destructive powers. The paper deals with Sacred Mahakala and it mentions legends, tales, myths in Hindus and Buddhist texts. It includes various types, forms and iconographic features of Mahakalas. This research concludes that sacred Mahakala is of great significance to both the Buddhist and the Hindus alike. Key-words: Sacred Mahakala, Hindu texts, Buddhist texts. Mahakala Newari Pauwa Etymology of the name Mahakala The word Mahakala is a Sanskrit word . Maha means ‘Great’ and Kala refers to ‘ Time or Death’ . Mahakala means “ Beyond time or Death”(Mukherjee, (1988). NY). The Tibetan Buddhism calls ‘Mahakala’ NagpoChenpo’ meaning the ‘ Great Black One’ and also ‘Ganpo’ which means ‘The Protector’. The Iconographic features of Mahakala in Hindu text In the ShaktisamgamaTantra. The male spouse of Mahakali is the outwardly frightening Mahakala (Great Time), whose meditatative image (dhyana), mantra, yantra and meditation . In the Shaktisamgamatantra, the mantra of Mahakala is ‘Hum Hum Mahakalaprasidepraside Hrim Hrim Svaha.’ The meaning of the mantra is that Kalika, is the Virat, the bija of the mantra is Hum, the shakti is Hrim and the linchpin is Svaha. -

The Yoga of the Inseparability of the Guru and Avalokiteshvara

The Source of All Attainments: The Yoga of the Inseparability of the Guru and Avalokiteshvara ༄༅། །害་མ་དང་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་དབ읺ར་མ읺ད་ཀི་讣ལ་ འབ일ར་དངBy일ས་གྲུབ་ʹན་འབྱུང་ཞ His Holiness the읺ས་ Fourteenthབ་བ་བ筴གས་ས 일། ། Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso Translated by Joona Repo FPMT Education Services Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. 1632 SE 11th Avenue Portland, OR 97214 USA www.fpmt.org © 2020 Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Set in Calibri 12/15, Century Gothic, Helvetica Light, Lydian BT, and Monlam Uni Ouchan 2. Page 4, line drawing of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Artist unknown. Technical Note Italics and a small font size indicate instructions and comments found in the Tibetan text and are not for recitation. Text not presented in bold or with no indentation is likewise not for recitation. Words in square brackets have been added by the translator for clarification. For example: This is how to correctly follow the virtuous friend, [the root of the path to full enlightenment]. A Guide to Pronouncing Sanskrit The following six points will enable you to learn the pronunciation of most transliterated Sanskrit mantras found in FPMT practice texts: 1. ŚH and ṢH are pronounced similar to the “sh” in “shoe.” 2. CH is pronounced similar to the “ch” in “chat.” CHH is also similar but is more heavily aspirated. -

Chapter X Sanctuaries on Mount Penanggungan |

Chapter X Sanctuaries on Mount Penanggungan: Candi Kendalisodo, Candi Yudha, and the Panji statue from Candi Selokelir – the climax geographical situation and layout of the sanctuaries Mount Penanggungan (1,653 m), situated approximately 50 kilometres to the south of Surabaya, has a peculiar shape (fig. 10.1). It has one cen- tral peak, which is surrounded by four lower summits and four more hills on a lower level, such that it resembles a natural mandala.1 The names of the four upper hills, starting from the one in the northeast and then proceeding clockwise, are Gajah Mungkur, Kemuncup, Sarahklopo, and Bekel (fig. 10.2). Most of the 81 sanctuaries or their remains are located on the northern and western slopes of the mountain.2 Many of the sanctuaries are grouped in such a way that their loca- tions follow an ascending line on the mountain slope – for example, sites LXI, LXII, LXIV, LXVII, and LX on the western slope, starting from Candi Jolotundo (XXVII). Others are grouped together in close proxim- ity – for instance, sites I, XVI, LIV, LII, LIII, LI, L, and IL on the upper western slope. Around Gajahmungkur ten sites are grouped close to each other: VII, XX, XXI, III, XIX, IX, XXII, XVIII, VIII, and LXIX.3 As not all the buildings are dated, we cannot conclude that these arrange- ments were the result of a plan. However, the addition of new sanctuar- ies may have allowed paths of procession and groups of sanctuaries to develop gradually. These sanctuary groups and lines may correspond with the so-called mandala which are mentioned in the Nagarakertagama 1 Compare my explanations on Mount Penanggungan in Chapter IV, sub-chapter ‘Water and moun- tain’.