The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum: a Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades One to Eight

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight INTRODUCTION TO THE AGA KHAN MUSEUM The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada is North America’s first museum dedicated to the arts of Muslim civilizations. The Museum aims to connect cultures through art, fostering a greater understanding of how Muslim civilizations have contributed to world heritage. Opened in September 2014, the Aga Khan Museum was established and developed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). Its state-of-the-art building, designed by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, includes two floors of exhibition space, a 340-seat auditorium, classrooms, and public areas that accommodate programming for all ages and interests. The Aga Khan Museum’s Permanent Collection spans the 8th century to the present day and features rare manuscript paintings, individual folios of calligraphy, metalwork, scientific and musical instruments, luxury objects, and architectural pieces. The Museum also publishes a wide range of scholarly and educational resources; hosts lectures, symposia, and conferences; and showcases a rich program of performing arts. Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight Patricia Bentley and Ruba Kana’an Written by Patricia Bentley, Education Manager, Aga Khan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Museum, and Ruba Kana’an, Head of Education and Scholarly reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any Programs, Aga Khan Museum, with contributions by: form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers. -

The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60954-8 - The Asian Military Revolution: From Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A. Lorge Frontmatter More information The Asian Military Revolution Records show that the Chinese invented gunpowder in the 800s. By the 1200s they had unleashed the first weapons of war upon their unsus- pecting neighbors. How did they react? What were the effects of these first wars? This extraordinarily ambitious book traces the history of that invention and its impact on the surrounding Asian world – Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia and South Asia – from the ninth through the twentieth century. As the book makes clear, the spread of war and its technology had devastating consequences on the political and cultural fabric of those early societies although each reacted very differently. The book, which is packed with information about military strategy, interregional warfare, and the development of armaments, also engages with the major debates and challenges traditional thinking on Europe’s contri- bution to military technology in Asia. Articulate and comprehensive, this book will be a welcome addition to the undergraduate classroom and to all those interested in Asian studies and military history. PETER LORGE is Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee. His previous publications include War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China (2005) and The International Reader in Military History: China Pre-1600 (2005). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60954-8 - The Asian Military Revolution: From Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A. Lorge Frontmatter More information New Approaches to Asian History This dynamic new series will publish books on the milestones in Asian history, those that have come to define particular periods or mark turning-points in the political, cultural and social evolution of the region. -

Mon Buddhist Architecture in Pakkret District, Nonthaburi Province, Thailand During Thonburi and Rattanakosin Periods (1767-1932)

MON BUDDHIST ARCHITECTURE IN PAKKRET DISTRICT, NONTHABURI PROVINCE, THAILAND DURING THONBURI AND RATTANAKOSIN PERIODS (1767-1932) Jirada Praebaisri* and Koompong Noobanjong Department of Industrial Education, Faculty of Industrial Education and Technology, King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, Bangkok 10520, Thailand *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: October 3, 2018; Revised: February 22, 2019; Accepted: April 17, 2019 Abstract This research examines the characteristics of Mon Buddhist architecture during Thonburi and Rattanakosin periods (1767-1932) in Pakkret district. In conjunction with the oral histories acquired from the local residents, the study incorporates inquiries on historical narratives and documents, together with photographic and illustrative materials obtained from physical surveys of thirty religious structures for data collection. The textual investigations indicate that Mon people migrated to the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya in large number during the 18th century, and established their settlements in and around Pakkret area. Located northwest of the present day Bangkok in Nonthaburi province, Pakkret developed into an important community of the Mon diasporas, possessing a well-organized local administration that contributed to its economic prosperity. Although the Mons was assimilated into the Siamese political structure, they were able to preserve most of their traditions and customs. At the same time, the productions of their cultural artifacts encompassed many Thai elements as well, as evident from Mon Buddhist temples and monasteries in Pakkret. The stylistic analyses of these structures further reveal the following findings. First, their designs were determined by four groups of patrons: Mon laypersons, elite Mons, Thai Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Studies Vol.19(1): 30-58, 2019 Mon Buddhist Architecture in Pakkret District Praebaisri, J. -

Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850

The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Benjamin, Jody A. 2016. The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493374 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 A dissertation presented by Jody A. Benjamin to The Department of African and African American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of African and African American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2016 © 2016 Jody A. Benjamin All rights reserved. Dissertation Adviser: Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong Jody A. Benjamin The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 Abstract This study re-examines historical change in western Africa during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through the lens of cotton textiles; that is by focusing on the production, exchange and consumption of cotton cloth, including the evolution of clothing practices, through which the region interacted with other parts of the world. It advances a recent scholarly emphasis to re-assert the centrality of African societies to the history of the early modern trade diasporas that shaped developments around the Atlantic Ocean. -

Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1

Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 2 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 3 4 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 စ Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 5 6 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 7 8 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 9 10 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Spatial Distribution Pattrens of Basic Education Schools in Pathein City Tin Tin Mya1, May Oo Nyo2 Abstract Pathein City is located in Pathein Township, western part of Ayeyarwady Region. The study area is included fifteen wards. This paper emphasizes on the spatial distribution patterns of these schools are analyzed by using appropriate data analysis methods. This study is divided into two types of schools, they are governmental schools and nongovernmental schools. Qualitative and quantitative methods are used to express the spatial distribution patterns of Basic Education Schools in Pathein City. Primary data are obtained from field surveys, informal interview, and open type interview .Secondary data are collected from the offices and departments concerned .Detailed facts are obtained from local authorities and experience persons by open type interview. Key words: spatial distribution patterns, education, schools, primary data ,secondary data Introduction The study area, Pathein City is situated in the Ayeyarwady Region. The study focuses only on the unevenly of spatial distribution patterns of basic education schools in Pathein City . -

The King's Nation: a Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand

THE KING’S NATION: A STUDY OF THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF NATION AND NATIONALISM IN THAILAND Andreas Sturm Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London (London School of Economics and Political Science) 2006 UMI Number: U215429 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U215429 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and entitled ‘The King’s Nation: A Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand’, represents my own work and has not been previously submitted to this or any other institution for any degree, diploma or other qualification. Andreas Sturm 2 VV Abstract This thesis presents an overview over the history of the concepts ofnation and nationalism in Thailand. Based on the ethno-symbolist approach to the study of nationalism, this thesis proposes to see the Thai nation as a result of a long process, reflecting the three-phases-model (ethnie , pre-modem and modem nation) for the potential development of a nation as outlined by Anthony Smith. -

The Social and Environmental Turn in Late 20Th Century Art

THE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL TURN IN LATE 20TH CENTURY ART: A CASE STUDY OF HELEN AND NEWTON HARRISON AFTER MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN MODERN THOUGHT AND LITERATURE AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY LAURA CASSIDY ROGERS JUNE 2017 © 2017 by Laura Cassidy Rogers. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/gy939rt6115 Includes supplemental files: 1. (Rogers_Circular Dendrogram.pdf) 2. (Rogers_Table_1_Primary.pdf) 3. (Rogers_Table_2_Projects.pdf) 4. (Rogers_Table_3_Places.pdf) 5. (Rogers_Table_4_People.pdf) 6. (Rogers_Table_5_Institutions.pdf) 7. (Rogers_Table_6_Media.pdf) 8. (Rogers_Table_7_Topics.pdf) 9. (Rogers_Table_8_ExhibitionsPerformances.pdf) 10. (Rogers_Table_9_Acquisitions.pdf) ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Zephyr Frank, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gail Wight I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ursula Heise Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. -

Hour by Hour!

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com -

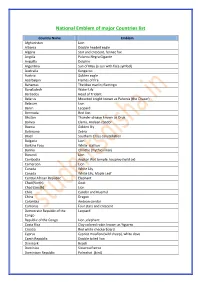

National Emblem of Major Countries List

National Emblem of major Countries list Country Name Emblem Afghanistan Lion Albania Double headed eagle Algeria Star and crescent, fennec fox Angola Palanca Negra Gigante Anguilla Dolphin Argentina Sun of May (a sun with face symbol) Australia Kangaroo Austria Golden eagle Azerbaijan Flames of fire Bahamas The blue marlin; flamingo Bangladesh Water Lily Barbados Head of Trident Belarus Mounted knight known as Pahonia (the Chaser) Belgium Lion Benin Leopard Bermuda Red lion Bhutan Thunder dragon known as Druk Bolivia Llama, Andean condor Bosnia Golden lily Botswana Zebra Brazil Southern Cross constellation Bulgaria Lion Burkina Faso White stallion Burma Chinthe (mythical lion) Burundi Lion Cambodia Angkor Wat temple, kouprey (wild ox) Cameroon Lion Canada White Lily Canada White Lily, Maple Leaf Central African Republic Elephant Chad(North) Goat Chad (South) Lion Chile Candor and Huemul China Dragon Colombia Andean condor Comoros Four stars and crescent Democratic Republic of the Leopard Congo Republic of the Congo Lion ,elephant Costa Rica Clay colored robin known as Yiguirro Croatia Red white checkerboard Cyprus Cypriot mouflon (wild sheep), white dove Czech Republic Double tailed lion Denmark Beach Dominica Sisserou Parrot Dominican Republic Palmchat (bird) Ecuador Andean condor Egypt Golden eagle Equatorial Guinea Silk cotton tree Eritrea Camel Estonia Barn swallow, cornflower Ethiopia Abyssinian lion European Union A circle of 12 stars Finland Lion France Lily Gabon Black panther Gambia Lion Georgia Saint George, lion Germany Corn -

World Wide Printing WORLD WIDE PRINTING 445 E

World Wide Printing WORLD WIDE PRINTING 445 E. FM 1382 and Publishing Incorporated Suite 3 - 713 Cedar Hill, Texas 75104 Phone: 1 972 780 2511 Fax: 1 972 780 2626 www.russianprinting.com [email protected] Printcorp 40 F.Skoriny St. Minsk, 220141, Belarus Phone: 375 17 267 7513 Fax: 375 17 265 9098 [email protected] www.printcorp.biz www.bibleprinting.org Dallas, Texas • Minsk, Belarus OUR FOUNDER, Gilbert Lindsay, started working in the printing industry in his father’s print shop. Today he leads one of the most unique printing companies in the world. WORLD WIDE PRINTING has been operating in the USSR/CIS since 1990. We have developed a full service printing company that makes timely worldwide deliveries to over 110 countries. World Wide Printing headquarters and sales office is located in the suburbs of Dallas, Texas. Our production facility is located in Minsk, Belarus, where 350 people are employed with 7,000 square meters of production area. WWP specializes in producing luxury bound books printed on thin paper, and economy editions at very competitive prices. DALLAS, TEXAS MINSK, BELARUS 2 CUSTOMER SERVICE We are able to communicate proficiently in several languages: French, Russian, and English. Our staff is very friendly, and ready to work with complicated jobs. QUALITY We are committed to producing quality products by using quality materials and maintaining a well-trained staff. RELIABILITY We give our customers honest answers and deliver the job when promised. 3 DALLAS, TEXAS World Wide Printing and Publishing headquarters and sales office. Gilbert Lindsay President CEO Shirley Lindsay Michael Lindsay Julia Lindsay Magann Marketing Manager Vice President Financial Controller OFFICES / STAFF OFFICES 4 Anna Lindsay Bookkeeper MINSK, BELARUS OFFICES / STAFF OFFICES Al Sadovsky Leonora Terentieva Deputy Director Production Senior Customer Service Manager Olga Yushkevich General Manager Elena Popova Olga Sadovskaya Head of Purchasing Dpt. -

Catalogue 119 Antiquariaat FORUM & ASHER Rare Books

Catalogue 119 antiquariaat FORUM & ASHER Rare Books Catalogue 119 ‘t Goy 2020 Antiquariaat Forum & Asher Rare Books Catalogue 119 1 Ex- tensive descriptions and images available on request. All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are in eur (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www. ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html> New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. ANTIL UARIAAT FOR?GE> 50 Y EARSUM @>@> Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 MS ‘t Goy 3997 MS ‘t Goy The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com covers: no. 203 on page 115. frontispiece: no. 108 on page 62. title page: no. 184 on page 104. v 1.2 · 07 Jul 2021 Christianity and children’s education intertwined: a very rare Italian ABC book 1. -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................