The Social and Environmental Turn in Late 20Th Century Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First U.S. Survey of Chilean Artist Juan Downey to Open at Bronx Museum of the Arts

FIRST U.S. SURVEY OF CHILEAN ARTIST JUAN DOWNEY TO OPEN AT BRONX MUSEUM OF THE ARTS Video and Photographic Installations, Paintings, and Drawings shed light on Downey’s Career Bronx, NY , DATE – Beginning February 9, 2012 The Bronx Museum of the Arts will present Juan Downey: The Invisible Architect , the first U.S. survey of the pioneering video artist Juan Downey. On view through May 20, 2012, the exhibition brings together more than 100 works from Downey’s expansive career, from his early experimental work with art and technology to his groundbreaking video art from the 1970s through the 1990s, the exhibition will include drawings, paintings, video and photographic installations, and the artist’s notebooks, which have never before been on view. “Downey revolutionized the field of video art and pioneered an art form that has had continued relevance for contemporary artists working today,” said Bronx Museum of the Arts Director Holly Block. “As a Chilean, Downey maintained a connection with Latin American culture throughout the many decades he lived and worked in New York. These dual influences give his work a special resonance with the Bronx Museum and with our community. In addition, Downey has exhibited at the Bronx Museum before, making this exhibition a homecoming of sorts.” Formally trained as an architect, Downey began experimenting with different art forms when he moved from Paris to Washington DC in 1965. He developed a strong interest in the concept of invisible energy and shifted from object-based artistic practice to an experiential approach, seeking to combine interactive performance with sculpture and video, a transition the exhibition explores. -

Airliner Crashes, Film Crew Killed Democrats Re-Elect Cummings

I MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, MARCH 14, 1974 - VOL, XOTI, No. 139 Manchester—A City of Village Charm TWENTY.FOUR PAGES - TWO SECTIONS PRICE, fiiTEEN CENTS __ __ _ Two Directors Plan Airliner Crashes, To Boycott Meeting . NEVADA • R«no Film Crew Killed By SOL R. COHEN saction. The directors censured him BISHOP,Calif. (U P I)-A The crew had beeq in the publicly and, on a proposal by Mrs. through the smoldering bodies chartered airliner carrying Mammoth Lakes area, filming Ferguson, agreed to conduct the perfor and airplane litter, across the Republican Directors Hillery Gallagher a film crew from the ABC- the third of a series “Primal mance review. snow-patched slope, “but we and Carl Zinsser are boycotting tonight’s TV series “Primal Man” Man: Struggle for Survival.” At its Feb. 12 meeting, the board voted couldn’t find any survivors so executive session of the Manchester Smn crashed into a mountain The series dramatizes the we shoved off.” unanimously to conduct the review on Board of Directors — called expressly for Franciftco evolution of human beings from March 12, tonight. However, it didn’t ridge in a remote area of a The accident occurred in reviewing the administrative perfor national forest Wednesday animal ancestorsjnto primitive ^>qar, night weather. specify whether the meeting would be men. mance of Town Manager Robert Weiss. night and exploded in a ball ’TeHms from the Forest Ser The boycott, they say in a joint state open or closed. ’That decision was made Tuesday night. CALIF. of fire, killing all 35 aboard. Mike Antonio, pilot for the vice, the^ Sierra Madre Search ment, “is because we feel we’re represen 5 Gallagher and Zinsser said today, The U.S. -

Are We There Yet?

ARE WE THERE YET? Study Room Guide on Live Art and Feminism Live Art Development Agency INDEX 1. Introduction 2. Lois interviews Lois 3. Why Bodies? 4. How We Did It 5. Mapping Feminism 6. Resources 7. Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION Welcome to this Study Guide on Live Art and Feminism curated by Lois Weaver in collaboration with PhD candidate Eleanor Roberts and the Live Art Development Agency. Existing both in printed form and as an online resource, this multi-layered, multi-voiced Guide is a key component of LADA’s Restock Rethink Reflect project on Live Art and Feminism. Restock, Rethink, Reflect is an ongoing series of initiatives for, and about, artists who working with issues of identity politics and cultural difference in radical ways, and which aims to map and mark the impact of art to these issues, whilst supporting future generations of artists through specialized professional development, resources, events and publications. Following the first two Restock, Rethink, Reflect projects on Race (2006-08) and Disability (2009- 12), Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three (2013-15) is on Feminism – on the role of performance in feminist histories and the contribution of artists to discourses around contemporary gender politics. Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three has involved collaborations with UK and European partners on programming, publishing and archival projects, including a LADA curated programme, Just Like a Woman, for City of Women Festival, Slovenia in 2013, the co-publication of re.act.feminism – a performing archive in 2014, and the Fem Fresh platform for emerging feminist practices with Queen Mary University of London. Central to Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three has been a research, dialogue and mapping project led by Lois Weaver and supported by a CreativeWorks grant. -

Current Issue of Saber

1st Cavalry Division Association Non-Profit Organization 302 N. Main St. US. Postage PAID Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 West, TX 76691 Change Service Requested Permit No. 39 SABER Published By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 70 NUMBER 4 Website: www.1CDA.org JULY / AUGUST 2021 It is summer and HORSE DETACHMENT by CPT Siddiq Hasan, Commander THE PRESIDENT’S CORNER vacation time for many of us. Cathy and are in The Horse Cavalry Detachment rode the “charge with sabers high” for this Allen Norris summer’s Change of Command and retirement ceremonies! Thankfully, this (704) 641-6203 the final planning stage [email protected] for our trip to Maine. year’s extended spring showers brought the Horse Detachment tall green pastures We were going to go for the horses to graze when not training. last year; however, the Maine authorities required either a negative test for Covid Things at the Horse Detachment are getting back into a regular swing of things or 14 days quarantine upon arrival. Tests were not readily available last summer as communities around the state begin to open and request the HCD to support and being stuck in a hotel 14 days for a 10-day vacation seemed excessive, so we various events. In June we supported the Buckholts Cotton Festival, the Buffalo cancelled. Thankfully we were able to get our deposits back. Soldier Marker Dedication, and 1CD Army Birthday Cake Cutting to name a few. Not only was our vacation cancelled but so were our Reunion and Veterans Day The Horse Detachment bid a fond farewell and good luck to 1SG Murillo and ceremonies. -

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism 1 Cover photo: Lancaster Boulevard in Lancaster, California. Source: City of Lancaster. Photo by Tamara Leigh Photography. Street design by Moule & Polyzoides. 25 GREAT IDEAS OF NEW URBANISM Author: Robert Steuteville, CNU Senior Dyer, Victor Dover, Hank Dittmar, Brian Communications Advisor and Public Square Falk, Tom Low, Paul Crabtree, Dan Burden, editor Wesley Marshall, Dhiru Thadani, Howard Blackson, Elizabeth Moule, Emily Talen, CNU staff contributors: Benjamin Crowther, Andres Duany, Sandy Sorlien, Norman Program Fellow; Mallory Baches, Program Garrick, Marcy McInelly, Shelley Poticha, Coordinator; Moira Albanese, Program Christopher Coes, Jennifer Hurley, Bill Assistant; Luke Miller, Project Assistant; Lisa Lennertz, Susan Henderson, David Dixon, Schamess, Communications Manager Doug Farr, Jessica Millman, Daniel Solomon, Murphy Antoine, Peter Park, Patrick Kennedy The 25 great idea interviews were published as articles on Public Square: A CNU The Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) Journal, and edited for this book. See www. helps create vibrant and walkable cities, towns, cnu.org/publicsquare/category/great-ideas and neighborhoods where people have diverse choices for how they live, work, shop, and get Interviewees: Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Jeff around. People want to live in well-designed Speck, Dan Parolek, Karen Parolek, Paddy places that are unique and authentic. CNU’s Steinschneider, Donald Shoup, Jeffrey Tumlin, mission is to help build those places. John Anderson, Eric Kronberg, Marianne Cusato, Bruce Tolar, Charles Marohn, Joe Public Square: A CNU Journal is a Minicozzi, Mike Lydon, Tony Garcia, Seth publication dedicated to illuminating and Harry, Robert Gibbs, Ellen Dunham-Jones, cultivating best practices in urbanism in the Galina Tachieva, Stefanos Polyzoides, John US and beyond. -

Alice Aycock: Sculpture and Projects

Alice Aycock: Sculpture and Projects. Cambridge and London: M.I.T. Press, 2005; pp. 1-8. Text © Robert Hobbs The Beginnings of a Complex The problem seems to be how to connect without connecting, how to group things together in such a way that the overall shape would resemble "the other shape, ifshape it might be called, that shape had none," referred to by Milton in Paradise Lost, how to group things haphazardly in much the way that competition among various interest groups produces a kind ofhaphazardness in the way the world looks and operates. The problem seems to be how to set up the conditions which would generate the beginnings ofa complex. Alice Aycock Project Entitled "The Beginnings ofa Complex . ." (1976-77): Notes, Drawings, Photographs, 1977 In Book 11 of Milton's Paradise Lost, Death assumes the guise of two wildly dissimilar figures near Hell's entrance, each with an extravagantly inconsistent appearance. The first, a trickster, appears as a fair woman from above the waist and a series of demons below, while the second-a "he;' according to Milton-is far more elusive. It assumes "the other shape" that Aycock refers to above. 1 When searching for a poetic image capable of communicating the world's elusiveness and indiscriminate randomness, Aycock remembered this description of Death's incommensurability, which she then incorporated into her artist's book Project Entitled "The Beginnings ofa Complex . ." (1976-77): Notes, Drawings, Photographs. Although viewing death in terms oflife is certainly not an innovation, as anyone familiar with Etruscan and Greco-Roman culture can testify, seeing life's complexity in terms of this shape-shifting allegorical figure signaling its end is a remarkable poetic enlists images from the past and from other inversion. -

Interview with Helen Meyer Harrison and Newton Harrison

Total Art Journal • Volume 1. No. 1 • Summer 2011 BETH AND ANNIE IN CONVERSATION, PART ONE: Interview with Helen Meyer Harrison and Newton Harrison Helen Meyer Harrison and Newton Harrison, The Lagoon Cycle, 1974-1984. Image Credit: The Harrison Studio Introduction by Elizabeth (Beth) Stephens Helen Meyer Harrison and Newton Harrison are two of the foremost artists practicing in the field of en- vironmental art today. I first met them in 2007 when they moved to Santa Cruz from San Diego where they were emeriti faculty from UC San Diego. In the early ‘70’s, they helped form UCSD’s Art Depart- ment into one of the most powerful centers for conceptual art in the country. They mentored artists such as Martha Rosler and Alan Sekula. Pauline Oliveros, Eleanor and David Antin, Alan Kaprow and Faith Ringgold were colleagues and together they formed a nurturing community for art and teaching. In addi- tion to their primary practice of environmental art, the Harrisons have also participated in a range of other historical and social movements, including the seminal west coast feminist art movement exemplified by works such as the 1972 installation Womanhouse. During that period they interacted with feminist artists and critics such as Arlene Raven, Miriam Shapiro, Judy Chicago and Suzanne Lacy. Even earlier, in 1962, Helen Harrison was the first New York coordinator for Women’s Strike for Peace. Newton Harrison Total Art Journal • Volume 1 No. 1 • Summer 2011 • http://www.totalartjournal.com served on the original board of directors of the Third World College, which Herbert Marcuse and Angela Davis initiated. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1980.Pdf

National Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. 20506 Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1980. Respectfully, Livingston L. Biddle, Jr. Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. February 1981 Contents Chairman’s Statement 2 The Agency and Its Functions 4 National Council on the Arts 5 Programs 6 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 32 Expansion Arts 52 Folk Arts 88 Inter-Arts 104 Literature 118 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 140 Museum 168 Music 200 Opera-Musical Theater 238 Program Coordination 252 Theater 256 Visual Arts 276 Policy and Planning 316 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 318 Challenge Grants 320 Endowment Fellows 331 Research 334 Special Constituencies 338 Office for Partnership 344 Artists in Education 346 Partnership Coordination 352 State Programs 358 Financial Summary 365 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 366 Chairman’s Statement The Dream... The Reality "The arts have a central, fundamental impor In the 15 years since 1965, the arts have begun tance to our daily lives." When those phrases to flourish all across our country, as the were presented to the Congress in 1963--the illustrations on the accompanying pages make year I came to Washington to work for Senator clear. In all of this the National Endowment Claiborne Pell and began preparing legislation serves as a vital catalyst, with states and to establish a federal arts program--they were communities, with great numbers of philanthro far more rhetorical than expressive of a national pic sources. -

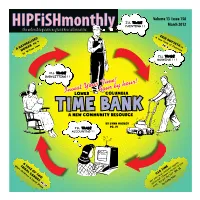

Hour by Hour!

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com -

Modernism Mummified Author(S): Daniel Bell Source: American Quarterly, Vol

Modernism Mummified Author(s): Daniel Bell Source: American Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 1, Special Issue: Modernist Culture in America (Spring, 1987), pp. 122-132 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2712633 . Accessed: 27/03/2014 09:37 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Thu, 27 Mar 2014 09:37:42 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions MODERNISM MUMMIFIED DANIEL BELL HarvardUniversity IN HIS INTRODUCTION TO THE IDEA OF THE MODERN,IRVING HOWE QUOTES THE famousremark of VirginiaWoolf, as everyonedoes sincehyperbole is arresting, that"on or aboutDecember 1910 humannature changed." Actually, Mrs. Woolf had writtenthat "human character changed." She was referring(in herfamous essay,"Mr. Bennettand Mrs. Brown,"written in 1924) to the changesin the positionof one's cook or of thepartners in marriage."All humanrelations have shifted-thosebetween masters and servants,husbands and wives,parents and children.And when human relations change there is at thesame time a changein religion,conduct, politics and literature."' Thissearch for a transfigurationinsensibility as thetouchstone of modernity has animatedother writers. -

Gender Performance in Photography

PHOTOGRAPHY (A CI (A CI GENDER PERFORMANCE IN PHOTOGRAPHY (A a C/VFV4& (A a )^/VM)6e GENDER PERFORMANCE IN PHOTOGRAPHY JENNIFER BLESSING JUDITH HALBERSTAM LYLE ASHTON HARRIS NANCY SPECTOR CAROLE-ANNE TYLER SARAH WILSON GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: front cover: Gender Performance in Photography Claude Cahun Organized by Jennifer Blessing Self- Portrait, ca. 1928 Gelatin-silver print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 11 'X. x 9>s inches (30 x 23.8 cm) January 17—April 27, 1997 Musee des Beaux Arts de Nantes This exhibition is supported in part by back cover: the National Endowment tor the Arts Nan Goldin Jimmy Paulettc and Tabboo! in the bathroom, NYC, 1991 €)1997 The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Cibachrome print, New York. All rights reserved. 30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) Courtesy of the artist and ISBN 0-8109-6901-7 (hardcover) Matthew Marks Gallery, New York ISBN 0-89207-185-0 (softcover) Guggenheim Museum Publications 1071 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10128 Hardcover edition distributed by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 100 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10011 Designed by Bethany Johns Design, New York Printed in Italy by Sfera Contents JENNIFER BLESSING xyVwMie is a c/\rose is a z/vxose Gender Performance in Photography JENNIFER BLESSING CAROLE-ANNE TYLER 134 id'emt nut files - KyMxUcuo&wuieS SARAH WILSON 156 c/erfoymuiq me c/jodt/ im me J970s NANCY SPECTOR 176 ^ne S$r/ of ~&e#idew Bathrooms, Butches, and the Aesthetics of Female Masculinity JUDITH HALBERSTAM 190 f//a« waclna LYLE ASHTON HARRIS 204 Stfrtists ' iyjtoqra/inies TRACEY BASHKOFF, SUSAN CROSS, VIVIEN GREENE, AND J. -

Real Academia De Bellas Artes De San Telmo De Málaga

ANUARIO 2015 REAL ACADEMIA DE BELLAS ARTES DE SAN TELMO DE MÁLAGA ANUARIO REAL ACADEMIA DE BELLAS ARTES DE SAN TELMO DE MÁLAGA 2015 NÚmero Quince. Segunda ÉPoca REAL ACADEMIA DE BELLAS ARTES DE SAN TELMO ASOCIADA AL INSTITUTO DE ESPAÑA INTEGRADA EN EL INSTITUTO DE ACADEMIAS DE ANDALUCÍA Esta Academia está constituida por treinta y ocho Académicos de Número, cinco Académicos de Honor y un número ilimitado de Académicos Correspondientes. Los Académicos de Número de esta Real Academia pertenecen a las siete secciones que la constituyen: Pintura, Arquitectura, Escultura, Música, Poesía y Literatura, Artes Visuales y Amantes de las Bellas Artes. SECCIÓN 1ª: PINTURA JUNTA DE GOBIERNO Ilmo. Sr. D. Rodrigo Vivar Aguirre La Junta de Gobierno de esta Real Academia está constituida Ilmo. Sr. D. Francisco Peinado Rodríguez por los Académicos de Número, que son elegidos de entre sus Ilmo. Sr. D. José Manuel Cabra de Luna miembros mediante las correspondientes elecciones convocadas de forma periódica. Actualmente está conformada por los académicos Ilmo. Sr. D. José Manuel Cuenca Mendoza (Pepe Bornoy) siguientes: Ilmo. Sr. D. Jorge Lindell Díaz Ilmo. Sr. D. José Guevara Castro Presidente: Excmo. Sr. D. José Manuel Cabra de Luna Ilmo. Sr. D. Manuel Pérez Ramos Vicepresidente 1°: Ilma. Sra. Dña. Rosario Camacho Martínez Ilmo. Sr. D. Fernando de la Rosa Ceballos Vicepresidente 2°: Ilmo. Sr. D. Ángel Asenjo Díaz Vicepresidente 3°: Ilmo. Sr. D. Francisco Javier Carrillo Montesinos SECCIÓN 2ª: ARQUITECTURA Secretaria: Ilma. Sra. Dña. Marion Reder Gadow Ilmo. Sr. D. Álvaro Mendiola Fernández Bibliotecaria: Ilma. Sra. Dña. María Pepa Lara García Ilmo. Sr.