Neil Sowards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typical Japanese Souvenirs Are a Kimono Or Yukata (Light, Cotton

JAPAN K N O W B E F O R E Y O U G O PASSPORT & VISA IMMUNIZATIONS All American and While no immunizations Canadian citizens must are required, you should have a passport which is consult your medical valid for at least 3 months provider for the most after your return date. No current advice. visa is required for stays See Travelers Handbook for up to 90 days. more information. ELECTRICITY TIME ZONE Electricity in Japan is 100 Japan is 13 hours ahead of volts AC, close to the U.S., Eastern Standard Time in our which is 120 volts. A voltage summer. Japan does not converter and a plug observe Daylight Saving adapter are NOT required. Time and the country uses Reduced power and total one time zone. blackouts may occur sometimes. SOUVENIRS Typical Japanese souvenirs CURRENCY are a Kimono or Yukata (light, The Official currency cotton summer Kimono), of Japan is the Yen (typically Geta (traditional footwear), in banknotes of 1,000, 5,000, hand fans, Wagasa and 10,000). Although cash (traditional umbrella), paper is the preferred method of lanterns, and Ukiyo-e prints. payment, credit cards are We do not recommend accepted at hotels and buying knives or other restaurants. Airports are weapons as they can cause best for exchanging massive delays at airports. currency. WATER WiFi The tap water is treated WiFi is readily available and is safe to drink. There at the hotels and often are no issues with washing on the high speed trains and brushing your teeth in and railways. -

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Nationalism by Design: the Politics of Dress in British Burma by Penny

-1- Nationalism by Design: The Politics of Dress in British Burma By Penny Edwards. IIAS Newsletter 46 (Winter 2008). Colonial attempts to hem in racial and gender difference through practice, law and lore made dress a potent field of resistance in British Burma, giving rise to new strands of nationalism by design. On 22 November 1921, a young male named Maung Ba Bwa was apprehended by police at the ShwedaGon PaGoda in RanGoon. MaunG Ba Bwa was one of an unusually hiGh number of Burmans visitinG the paGoda on this November evening for an exhibition of weaving, and a performance of a phwe (Burmese traditional theatre) by two leadinG artists. In MaunG Ba Bwa’s recollection of events, “his attire” had attracted police attention. “He was wearinG a pinni jacket and Yaw longyi, obviously rather self-consciously and in demonstration of his nationalist sympathies,” stated the resultant police report; “He seems, possibly not without reason, to think that some Government officers reGard such clothes with disapproval.” MaunG Ba Bwa was brouGht in for questioninG followinG the storminG of the ShwedaGon by British and Indian police, when Gurkhas “desecrated the paGoda by rushing up the steps with their boots on.” In the ensuinG fracas, which pitted monks aGainst such colonial aGents of ‘order,’ a Burmese civilian was killed. The scholar- official J. S. Furnivall, who presided over an independent commission of inquiry into the police response, would also pin his diaGnosis of Maung Ba Bwa’s political orientation on his wardrobe. His pinni jacket and his longyi, the commission reported, were proof positive of his “nationalist sentiment.”1 Wearing your politics on your sleeve By the early 1920s, in a climate where speakinG out or publishinG critiques of colonialism saw some younG monks and other activists jailed for years, increasinG numbers of Burmese civilians -- like MaunG Ba Bwa -- chose to express their political leaninGs in their dress. -

Buddhism in Myanmar a Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1

Buddhism in Myanmar A Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1. Earliest Contacts with Buddhism 2. Buddhism in the Mon and Pyu Kingdoms 3. Theravada Buddhism Comes to Pagan 4. Pagan: Flowering and Decline 5. Shan Rule 6. The Myanmar Build an Empire 7. The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Notes Bibliography Preface Myanmar, or Burma as the nation has been known throughout history, is one of the major countries following Theravada Buddhism. In recent years Myanmar has attained special eminence as the host for the Sixth Buddhist Council, held in Yangon (Rangoon) between 1954 and 1956, and as the source from which two of the major systems of Vipassana meditation have emanated out into the greater world: the tradition springing from the Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw of Thathana Yeiktha and that springing from Sayagyi U Ba Khin of the International Meditation Centre. This booklet is intended to offer a short history of Buddhism in Myanmar from its origins through the country's loss of independence to Great Britain in the late nineteenth century. I have not dealt with more recent history as this has already been well documented. To write an account of the development of a religion in any country is a delicate and demanding undertaking and one will never be quite satisfied with the result. This booklet does not pretend to be an academic work shedding new light on the subject. It is designed, rather, to provide the interested non-academic reader with a brief overview of the subject. The booklet has been written for the Buddhist Publication Society to complete its series of Wheel titles on the history of the Sasana in the main Theravada Buddhist countries. -

ASEAN Information 1. Bangkok Is the Capital City of Thailand. 2. Jakarta Is

ASEAN information ASEAN Study Centre Kanlayanawat Sister School (Credit by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand) 1. Bangkok is the capital city of Thailand. 2. Jakarta is the capital city of Indonesia. 3. Timor-Leste is the newest country formed in Southeast Asia in 2002. Its capital city is Dili. 4. Hanoi is the capital city of Vietnam. 5. As the capital city of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur is an international business centre with modern transportation. It has buildings of different styles: Malay, Chinese, Indian, British and European. Kelantan has many beautiful beaches and is famous for Malay crafts like silver, kites and batik. Kedah has many rice fields and is near Thailand, so it shares some cultural traditions with Thailand. 6. The Mekong River is the “Mother of Rivers”. It is the longest river in Southeast Asia. It is 4,200 kilometers long and flows through 6 countries. It starts in China and crosses Myanmar, Lao, Thailand, Cambodia and then Vietnam. The Mekong River is important to the farmers, animals and plants in Southeast Asia. It remains us that we have many common lifestyles and cultures, and that we must co-operate with our neighbors. 7. Indonesia has over 17,000 islands and 250 million people. In Southeast Asia, it has the most number of different languages and cultures. In the past, Indonesia was ruled by Portugal, Holland, British and Japan. In religion and art, it has Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Buddhist influences. The national language is called Bahasa Indonesia. Indonesia hopes for “Unity in Diversity”, so that everyone can live in peace. -

Back on the Tourist Trail After Almost 20 Years, Yangon

FLY MYANMAR ORNING COMES early here. By 5am, the streets are full of vendors, all getting ready to cook breakfast for the city’s hungry workforce. Chai is the country’s GOLDEN morning drink of choice and is served in small glass cups, steaming hot and very sweet. !e little wooden chairs outside the vendors’ stalls are soon filled, as men and sarong-clad women stop for a hot drink before getting on with their day. MOMENTS It is a familiar scene in many cities across Asia, but this is not one of the continent’s more well-known visi- Yangon tor locales, such as Bangkok, Hanoi or even Beijing. Rangoon !is is Yangon, formerly known as Rangoon and, not Myanmar TEXT/ CORI HOWARD so long ago, the capital of Myanmar, a country still Burma more familiar to many as Burma. 2006 Supplanted by Naypyidaw as the country’s capital in Back on the tourist trail after almost 2006, Yangon remains Myanmar’s busiest and most 20 populous city. It is getting used to welcoming visitors 20 years, Yangon offers a whole new again, with various political wranglings, both domesti- generation a wonderful taste of cally and internationally, keeping it off the tourist trail for almost 20 years. Myanmar’s culture, cuisine and history !e drive from the gleaming, new international air- port into Yangon takes you through dusty, bustling roads where street hawkers sell piles of old shoes and 20 women walk by balancing heavily laden baskets of fruit on their heads. Barefoot monks in saffron robes shade their shaved heads from the hot sun with rattan fans, while bare-chested men in sarongs pedal rickshaws alongside diesel-belching buses and the occasional, somewhat incongruous, brand-new SUV. -

The Flower of Gala Water V Ery Much

THE FLO WER O F GALA WATER . N ovel fl . M S AME L V R . I A E BAR R , ’ “ ” “ A u th o r o Girls o a Feath er T/ze Beads o f f , f ” “ ” Tasmer Frien d O livia etc , , . B WI TH I L L U S T A T I ON S B Y o . K EN DR I CK . Q/ N EW YO R K BE B E ’ S S O N S R O R T O N N R , P U BL I SHERS . m N N O . 1 10 “8 0 5 0 MO NTHLY. S U MORI PTIO N P R I CZ S I ! DO LL RS P K G N U AL OHO IO! OK R I I O , A A ‘ ’ N "l. “A7YI R . ( 74 75 0 5 0 AT I Hl N EW YO RK N . Y . FOOT O 'P IC! AO S ECO D O L O. Al J A NUA RY 1 , , , A The Flower of ala Water G . T CHAP ER I . FL W O F G L W THE O ER A A ATER. W an water fro m th e B o rder h ills ear v o ce fro th e o ld ears D i m y , Th d stant m usic lu lls and st lls y i i , And o ves t o u et tears m q i . A mist o f m em o ry bro o ds and flo ats Th e B o rder W ate rs flo w ; air i ullo f ballad n o t Th e s f es, ” o f lo n a B o rn o ut g go . -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006

Burma Page 1 of 24 2005 Human Rights Report Released | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Burma Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Since 1962, Burma, with an estimated population of more than 52 million, has been ruled by a succession of highly authoritarian military regimes dominated by the majority Burman ethnic group. The current controlling military regime, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, is the country's de facto government, with subordinate Peace and Development Councils ruling by decree at the division, state, city, township, ward, and village levels. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a generally free and fair parliamentary election, but the junta refused to recognize the results. Twice during the year, the SPDC convened the National Convention (NC) as part of its purported "Seven-Step Road Map to Democracy." The NC, designed to produce a new constitution, excluded the largest opposition parties and did not allow free debate. The military government totally controlled the country's armed forces, excluding a few active insurgent groups. The government's human rights record worsened during the year, and the government continued to commit numerous serious abuses. The following human rights abuses were reported: abridgement of the right to change the government extrajudicial killings, including custodial deaths disappearances rape, torture, and beatings of -

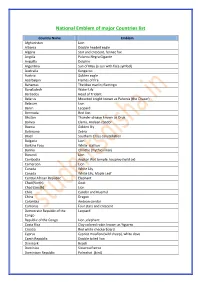

National Emblem of Major Countries List

National Emblem of major Countries list Country Name Emblem Afghanistan Lion Albania Double headed eagle Algeria Star and crescent, fennec fox Angola Palanca Negra Gigante Anguilla Dolphin Argentina Sun of May (a sun with face symbol) Australia Kangaroo Austria Golden eagle Azerbaijan Flames of fire Bahamas The blue marlin; flamingo Bangladesh Water Lily Barbados Head of Trident Belarus Mounted knight known as Pahonia (the Chaser) Belgium Lion Benin Leopard Bermuda Red lion Bhutan Thunder dragon known as Druk Bolivia Llama, Andean condor Bosnia Golden lily Botswana Zebra Brazil Southern Cross constellation Bulgaria Lion Burkina Faso White stallion Burma Chinthe (mythical lion) Burundi Lion Cambodia Angkor Wat temple, kouprey (wild ox) Cameroon Lion Canada White Lily Canada White Lily, Maple Leaf Central African Republic Elephant Chad(North) Goat Chad (South) Lion Chile Candor and Huemul China Dragon Colombia Andean condor Comoros Four stars and crescent Democratic Republic of the Leopard Congo Republic of the Congo Lion ,elephant Costa Rica Clay colored robin known as Yiguirro Croatia Red white checkerboard Cyprus Cypriot mouflon (wild sheep), white dove Czech Republic Double tailed lion Denmark Beach Dominica Sisserou Parrot Dominican Republic Palmchat (bird) Ecuador Andean condor Egypt Golden eagle Equatorial Guinea Silk cotton tree Eritrea Camel Estonia Barn swallow, cornflower Ethiopia Abyssinian lion European Union A circle of 12 stars Finland Lion France Lily Gabon Black panther Gambia Lion Georgia Saint George, lion Germany Corn -

Ageless Cities of Time

AGELESS CITIES OF TIME 1 INTRODUCTION The ancient cities in Myanmar are a wonder to behold as they still retain their striking beauty of timeless buildings, despite being worn by age and time. Several iconic landmarks present in these cities hold historical value that tells a story of the rise and fall of the kingdom, the glory of a capital, and the spread of Theravada Buddhism within the nation. You will discover much in these cities; from temples erected thousands of years ago, a township with excavated archaeological sites, and the prominence of Myanmar’s changing capitals, this is a land with an exciting history to tell. You’ll be taken in wonder as you visit all of Myanmar’s ancient civilisations and learn how the origins and history that led to the developing nation we see today. 2 PYU CITIES The Pyu Cities comprise of Halin, Beikthano and Sri Kestra. These sites have been excavated and are part of the Pyu Kingdom, which stretched from Tagaung in the north to the Ayeyarwady River and to south of present-day Daw. History During 832CE, the Pyu kingdom was attacked by an army of Nanzhao who kidnapped 3,000 citizens and took them away. The remaining citizens left behind went on to blend with the rest of Bamar society, which settled along the upper Ayeyarwady banks by the end of 800CE. Highlights Sri Kestra was excavated in 1926 and there was relic chambers that were discovered to hold a twenty-page Buddhist manuscript and gilded Buddha images. There were also three pagodas: Payama, Payagyi and Bawbawgyi that points to Sri Kestra being a centre for early Buddhism in Myanmar. -

The Hitler Youth Movement, 1933-1945

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1954 The Hitler Youth Movement, 1933-1945 Forest Ernest Barber Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Barber, Forest Ernest, "The Hitler Youth Movement, 1933-1945" (1954). Master's Theses. 905. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/905 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1954 Forest Ernest Barber • A 'fHBSIS BUB.\{l'n'ED TO nm 'ACULT! OJ' THE ClRAOOAft SOHOOL 0' LOIOLA UNlftlSITY IN fA.BfIAL JULFU,z,MSIT OF 'DIS DQUlrw&NTS FOR 'l'BE l'lIGIIIt or *~aO'A~ . A Good Oull,"Y)e For ~ I=-uture TheSIS / 1922. ae .. pwlua,*, fItoa 1IDeae1aer Publ1c High Scbool, leaualaer, Ind1aDlt June, 19lil, and. troa Ju\l.a> tJn1'ftft1t1'. I.Uan.poU., IDd:5u., June, 1945, w1tth the de&:&'ee of Baohelor of Sc1-... FI"OJI 1945 to 19la6 the author taUlh' 1ft aa.-, CUba. r.om 11&16 to 1948 he taught in'tbeU, QfteoeJ ard btoa 1948 tto 19S1 M acted. .. 8D Educa\i.or& Adv.1.r 1n the Troop Infonatial and Ed.... t14n Propaa, tl'D1tecl statM AJ:vlT of OCovpa1d.OD, ~. ForeA Emen ~ 'bepn bJ.a pa4uate durU..