Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Message from the Governor of Bangkok

MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR OF BANGKOK Bangkok is one of the world’s most our people are encouraged to pay dynamic cities. For more than 224 more participation in several activities years of history, art, culture and conducted by Bangkok Metropolitan architecture, it is the pride of Thailand Administration to further enhance the and a place of warm welcome for local administration process. visitors. Named the Best Tourism City in Asia, Bangkok boasts a fascinating ‘Your Key to Bangkok’ is considered array of sights and experience that as a window to all aspects of the city. are both unique and accessible. With its most comprehensive information, you will be revealed all Emphasizing on its geographic the features, facts and fi gures as well characteristic, Bangkok is a veritable as other details concerning our city. gateway to other Southeast Asian cities. With its wealth of well-educated I would like to take this opportunity to human resource, network of express my heartiest welcome to you transportation, infrastructure and IT to Bangkok to explore many treasures system, it is drawing attention from that the City of Angels has to offer. the world as a business hub with abundant opportunities brought by a number of world-class enterprises. In the attempt to become an international metropolis, Bangkok is promoting several programs to pursue our goal to be a livable city, a city of investment and a tourism city. We are also encouraging more initiatives in order (Mr. Apirak Kosayodhin) to ensure the well-being of Bangkok Governor of Bangkok -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Symbolism of the Buddhist Stūpa

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Gregory Schopen Roger Jackson Indiana University Fairfield University Bloomington, Indiana, USA Fairfield, Connecticut, USA EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Bardxvell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfteld, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Bruce Cameron Hall College of William and Mary Williamsburg, Virginia, USA Volume 9 1986 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. Signs, Memory and History: A Tantric Buddhist Theory of Scriptural Transmission, by Janet Gyatso 7 2. Symbolism of the Buddhist Stupa, by Gerard Fussman 37 3. The Identification of dGa' rab rdo rje, by A. W. Hanson-Barber 5 5 4. An Approach to Dogen's Dialectical Thinking and Method of Instantiation, by Shohei Ichimura 65 5. A Report on Religious Activity in Central Tibet, October, 1985, by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. and Cyrus Stearns 101 6. A Study of the Earliest Garbha Vidhi of the Shingon Sect, by Dale Allen Todaro 109 7. On the Sources for Sa skya Panclita's Notes on the "bSam yas Debate," by Leonard W.J. van der Kuijp 147 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. The Bodymind Experience in Japanese Buddhism: A Phenomenological Study ofKukai and Dogen, by D. Shaner (William Waldron) 155 2. A Catalogue of the s Tog Palace Kanjur, by Tadeusz Skorupski (Bruce Cameron Hall) 156 3. Early Buddhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study of the Founders' Authority, the Community, and the Discipline, by Chai-Shin Yu (Vijitha Rajapakse) 162 4. -

From Charlemagne to Hitler: the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and Its Symbolism

From Charlemagne to Hitler: The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and its Symbolism Dagmar Paulus (University College London) [email protected] 2 The fabled Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire is a striking visual image of political power whose symbolism influenced political discourse in the German-speaking lands over centuries. Together with other artefacts such as the Holy Lance or the Imperial Orb and Sword, the crown was part of the so-called Imperial Regalia, a collection of sacred objects that connotated royal authority and which were used at the coronations of kings and emperors during the Middle Ages and beyond. But even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the crown remained a powerful political symbol. In Germany, it was seen as the very embodiment of the Reichsidee, the concept or notion of the German Empire, which shaped the political landscape of Germany right up to National Socialism. In this paper, I will first present the crown itself as well as the political and religious connotations it carries. I will then move on to demonstrate how its symbolism was appropriated during the Second German Empire from 1871 onwards, and later by the Nazis in the so-called Third Reich, in order to legitimise political authority. I The crown, as part of the Regalia, had a symbolic and representational function that can be difficult for us to imagine today. On the one hand, it stood of course for royal authority. During coronations, the Regalia marked and established the transfer of authority from one ruler to his successor, ensuring continuity amidst the change that took place. -

Thai Kingship During the Ayutthaya Period : a Note on Its Divine Aspects Concerning Indra*

Thai Kingship during the Ayutthaya Period : A Note on Its Divine Aspects Concerning Indra* Woraporn Poopongpan Abstract This article is an initial attempt to highlight the divine aspects of Thai kingship during the Ayutthaya period, the interesting characteristic of which was an association of the king’s divinity with the Buddhist and Brahman god, Indra. Thai concept of the king’s divinity was identified closely with many Brahman gods such as Narayana, Rama or Siva (Isuan) but the divine aspects concerning Indra had a special place in Thai intellectual thinking as attested by ceremonies associated with the kingship recorded in Palatine Law and other sources. Thai kingship associated with Indra was reflected in the following elements: 1. The Royal ceremonies 2. The names of Indra’s residences 3. The number of the king’s consorts The article concludes that the emphasis on the king’s divine being as Indra derived not only from the influence of Brahmanism on the Thai society but more importantly from the high status of Indra in Buddhist belief. This can be easily understood since Buddhism is the main religion of Thai society. While some aspects * This article is based on the PhD dissertation “The Palatine Law as a source for Thai History from Ayutthaya period to 1805”, Submitted to the Department of History, Chulalongkorn University. It would not have been possible without considerable helps and valuable guidance from Dr. Dhiravat na Pombejra, my advisor, and all kind helps from Miss Apinya Odthon, my close friend. Silpakorn University International Journal Vol.7 : 143-171, 2007 Ayutthaya Thai Kingship Concerning Indra Silpakorn University International Journal Vol.7, 2007 of kingship are derived from Brahmanic Indra because Thailand adopted several conceptions of state and kingship from India, it was the Thai Buddhist understanding of Indra as a supporter of the Buddha that had a more significant impact. -

ROYAL CORONATION EVENTS HELD in PHUKET SPORT PAGE 32 Bangers Belles the Phuket News the Events Are As Follows: Ceremony to Pay Respects to His Hearts”

THEPHUKETNEWS.COM FRIDAY, MAY 3, 2019 thephuketnews thephuketnews1 thephuketnews.com Friday, May 3 – Thursday, May 9, 2019 Since 2011 / Volume IX / No. 18 20 Baht HEAVY RAINS BRING END TO WATER SHORTAGES > PAGE 2 NEWS PAGE 3 National forest luxury mansion deemed illegal LIFE PAGE 11 Rediscover Thai cuisine at The Plantation Club Phuket Governor Phakaphong Tavipatana pays homage to His Majesty The King during a ceremony earlier this week. Photo: Phuket PR ROYAL CORONATION EVENTS HELD IN PHUKET SPORT PAGE 32 Bangers Belles The Phuket News The events are as follows: Ceremony to pay respects to His hearts”. Participants are to meet at [email protected] Saturday, May 4 Majesty the King, and screening of the 4,000-seat indoor gymnasium at 7am: Merit making ceremony and the live broadcast of the nationally Saphan Hin. back to defend he Phuket office of the Public ceremony to pay respect to HM The televised program at Phuket 4pm – 5:50pm. Ceremony to pay Rugby 10s title Relations Department of King at Wat Phra Thong in Thalang. Provincial Hall in Phuket Town. respect to His Majesty The King at TThailand has released 9am – 5pm: Live broadcast of the People attending the event must wear Phuket Provincial Hall, led by Phuket a notice announcing the official nationally televised program at Wat a yellow shirt. Governor Phakaphong Tavipatana. public events to be held to mark Phra Thong. Volunteers will be present Monday, May 6 Screening of the live broadcast the Royal Coronation of His to provide assistance. People attending 8am: Royal Coronation event vol- at Phuket Provincial Hall of the Majesty King Maha Vajiralongkorn the event must wear a yellow shirt. -

Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities

Dr. K. Warikoo 1 © Vivekananda International Foundation 2020 Published in 2020 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg | Chanakyapuri | New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764 | Fax: 011-66173415 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vifindia.org Follow us on Twitter | @vifindia Facebook | /vifindia All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher Dr. K. Warikoo is former Professor, Centre for Inner Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is currently Senior Fellow, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi. This paper is based on the author’s writings published earlier, which have been updated and consolidated at one place. All photos have been taken by the author during his field studies in the region. Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities India and Eurasia have had close social and cultural linkages, as Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia, Mongolia, Buryatia, Tuva and far wide. Buddhism provides a direct link between India and the peoples of Siberia (Buryatia, Chita, Irkutsk, Tuva, Altai, Urals etc.) who have distinctive historico-cultural affinities with the Indian Himalayas particularly due to common traditions and Buddhist culture. Revival of Buddhism in Siberia is of great importance to India in terms of restoring and reinvigorating the lost linkages. The Eurasianism of Russia, which is a Eurasian country due to its geographical situation, brings it closer to India in historical-cultural, political and economic terms. -

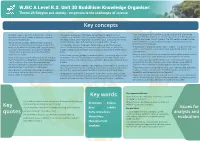

Key Words Key Quotes Key Concepts

WJEC A Level R.S. Unit 3D Buddhism Knowledge Organiser: Theme 2B Religion and society - responses to the challenges of science Key concepts • Buddhism rejects any form of blind faith – what is • The realms and beings within them are described in detail in various • From one perspective, Buddhism is closely aligned with science: the required is akaravati saddha (confidence based on traditions e.g. Hot Ashes Hell, 31 planes of existence in the universe divided Japanese Buddhist philosopher Inoue Enryo stated that Buddhism was reason and experience). into three realms, Mount Meru, the King of the devas, Sakra who lives on the scientific and based on fact; Huxley in the 19th century argued that the law of karma was an observable law of the universe because it was • Blindly clinging to views rather than fully grasping summit of Mount Meru in Tavatimsa one of the Buddhist heavens. entirely based on causation. the dhamma is likened to the wrong grasping of the • HH the Dalai Lama has assessed science to be of great importance in water-snake which will lead it to bite a person; wrong Tibetan Buddhism: viewing the moon through a telescope as young boy • The Dalai Lama argues Buddhism does not reify – make what is abstract grasping of the dhamma can only be countered made him begin to doubt Buddhist cosmology as found in the Abhidhamma such as God ‘material’ – and is thus more aligned with science than through close questioning of the Buddha and of Pitaka. many religions. experienced monks. • In 2000, he introduced modern science education –psychology, physics and • Sunyata, anicca, and anatta are compatible with modern science such as • In the Kalama Sutta, the Buddha teaches the Kalamas astronomy – into the Tibetan monastic curriculum; he endorsed the use of quantum physics and new discoveries about how the mind works. -

The Yoga of the Inseparability of the Guru and Avalokiteshvara

The Source of All Attainments: The Yoga of the Inseparability of the Guru and Avalokiteshvara ༄༅། །害་མ་དང་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་དབ읺ར་མ읺ད་ཀི་讣ལ་ འབ일ར་དངBy일ས་གྲུབ་ʹན་འབྱུང་ཞ His Holiness the읺ས་ Fourteenthབ་བ་བ筴གས་ས 일། ། Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso Translated by Joona Repo FPMT Education Services Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. 1632 SE 11th Avenue Portland, OR 97214 USA www.fpmt.org © 2020 Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Set in Calibri 12/15, Century Gothic, Helvetica Light, Lydian BT, and Monlam Uni Ouchan 2. Page 4, line drawing of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Artist unknown. Technical Note Italics and a small font size indicate instructions and comments found in the Tibetan text and are not for recitation. Text not presented in bold or with no indentation is likewise not for recitation. Words in square brackets have been added by the translator for clarification. For example: This is how to correctly follow the virtuous friend, [the root of the path to full enlightenment]. A Guide to Pronouncing Sanskrit The following six points will enable you to learn the pronunciation of most transliterated Sanskrit mantras found in FPMT practice texts: 1. ŚH and ṢH are pronounced similar to the “sh” in “shoe.” 2. CH is pronounced similar to the “ch” in “chat.” CHH is also similar but is more heavily aspirated. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 313 International Conference on Rural Studies in Asia (ICoRSIA 2018) Nyadran Gunung Silurah: The Role of Mountain for Religious Life of Ancient Batang Society in Central Java (VII–IX Century) Ufi Saraswati Faculty of Social Sciences, Universitas Negeri Semarang Semarang, Indonesia Corresponding email: [email protected] Abstract—The tradition of Nyadran Gunung Silurah fed by five rivers. These rivers are used as a liaison which conducted by the Silurah village community in has an easy access into and out of the district of Batang, Wonotunggal District, Batang Regency, reaffirms the belief so this area could potentially be an important region of the Batang community of the Ancient VII-IX century. It which serves as a vehicle forming the pattern of people's is about the existence of the concept of the holy mountain as activities from over time. the center of the universe. In ancient Javanese society, there is a belief that the kingdom of the gods was at the peak of Physical appearance condition of Batang distinctive the sacred mountain called Meru/Mahameru. Mountain in region with mountain peaks that make up the air Prahu the Hindu doctrine is believed to be the main pillar of the "serrations" becomes very easy to recognize from the sea. world called axis (axis mundi). Mount as a pivot (axis Sighting peak of Mount Prahu air has "serrations" because mundi) to the stairs is up to the world of gods located on top Mount Prahu is a cluster of five mountains with different of the mountain (Meru/Mahameru). -

Chapter X Sanctuaries on Mount Penanggungan |

Chapter X Sanctuaries on Mount Penanggungan: Candi Kendalisodo, Candi Yudha, and the Panji statue from Candi Selokelir – the climax geographical situation and layout of the sanctuaries Mount Penanggungan (1,653 m), situated approximately 50 kilometres to the south of Surabaya, has a peculiar shape (fig. 10.1). It has one cen- tral peak, which is surrounded by four lower summits and four more hills on a lower level, such that it resembles a natural mandala.1 The names of the four upper hills, starting from the one in the northeast and then proceeding clockwise, are Gajah Mungkur, Kemuncup, Sarahklopo, and Bekel (fig. 10.2). Most of the 81 sanctuaries or their remains are located on the northern and western slopes of the mountain.2 Many of the sanctuaries are grouped in such a way that their loca- tions follow an ascending line on the mountain slope – for example, sites LXI, LXII, LXIV, LXVII, and LX on the western slope, starting from Candi Jolotundo (XXVII). Others are grouped together in close proxim- ity – for instance, sites I, XVI, LIV, LII, LIII, LI, L, and IL on the upper western slope. Around Gajahmungkur ten sites are grouped close to each other: VII, XX, XXI, III, XIX, IX, XXII, XVIII, VIII, and LXIX.3 As not all the buildings are dated, we cannot conclude that these arrange- ments were the result of a plan. However, the addition of new sanctuar- ies may have allowed paths of procession and groups of sanctuaries to develop gradually. These sanctuary groups and lines may correspond with the so-called mandala which are mentioned in the Nagarakertagama 1 Compare my explanations on Mount Penanggungan in Chapter IV, sub-chapter ‘Water and moun- tain’. -

Reading the History of a Tibetan Mahakala Painting: the Nyingma Chod Mandala of Legs Ldan Nagpo Aghora in the Roy Al Ontario Museum

READING THE HISTORY OF A TIBETAN MAHAKALA PAINTING: THE NYINGMA CHOD MANDALA OF LEGS LDAN NAGPO AGHORA IN THE ROY AL ONTARIO MUSEUM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Aoife Richardson, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. John C. Huntington edby Dr. Susan Huntington dvisor Graduate Program in History of Art ABSTRACT This thesis presents a detailed study of a large Tibetan painting in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) that was collected in 1921 by an Irish fur trader named George Crofts. The painting represents a mandala, a Buddhist meditational diagram, centered on a fierce protector, or dharmapala, known as Mahakala or “Great Black Time” in Sanskrit. The more specific Tibetan form depicted, called Legs Idan Nagpo Aghora, or the “Excellent Black One who is Not Terrible,” is ironically named since the deity is himself very wrathful, as indicated by his bared fangs, bulging red eyes, and flaming hair. His surrounding mandala includes over 100 subsidiary figures, many of whom are indeed as terrifying in appearance as the central figure. There are three primary parts to this study. First, I discuss how the painting came to be in the museum, including the roles played by George Croft s, the collector and Charles Trick Currelly, the museum’s director, and the historical, political, and economic factors that brought about the ROM Himalayan collection. Through this historical focus, it can be seen that the painting is in fact part of a fascinating museological story, revealing details of the formation of the museum’s Asian collections during the tumultuous early Republican era in China.