Key Words Key Quotes Key Concepts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-08-17 Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography Ereshefsky, Joshua Ian Ereshefsky, J. I. (2020). Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112477 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography by Joshua Ian Ereshefsky A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA AUGUST, 2020 © Joshua Ian Ereshefsky 2020 i ABSTRACT Buddhists, across different schools and regions, traditionally posited a similar world model—one that is flat and centered by giant Mount Meru. This world model is chiefly featured in Vasubandhu’s fourth century CE text, the Abhidharmakośabhāṣyam. In 1552, Christian missionary Francis Xavier introduced European spherical-world cosmography to Japan, precipitating what this thesis terms the Buddhist -

Symbolism of the Buddhist Stūpa

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Gregory Schopen Roger Jackson Indiana University Fairfield University Bloomington, Indiana, USA Fairfield, Connecticut, USA EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Bardxvell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfteld, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Bruce Cameron Hall College of William and Mary Williamsburg, Virginia, USA Volume 9 1986 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. Signs, Memory and History: A Tantric Buddhist Theory of Scriptural Transmission, by Janet Gyatso 7 2. Symbolism of the Buddhist Stupa, by Gerard Fussman 37 3. The Identification of dGa' rab rdo rje, by A. W. Hanson-Barber 5 5 4. An Approach to Dogen's Dialectical Thinking and Method of Instantiation, by Shohei Ichimura 65 5. A Report on Religious Activity in Central Tibet, October, 1985, by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. and Cyrus Stearns 101 6. A Study of the Earliest Garbha Vidhi of the Shingon Sect, by Dale Allen Todaro 109 7. On the Sources for Sa skya Panclita's Notes on the "bSam yas Debate," by Leonard W.J. van der Kuijp 147 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. The Bodymind Experience in Japanese Buddhism: A Phenomenological Study ofKukai and Dogen, by D. Shaner (William Waldron) 155 2. A Catalogue of the s Tog Palace Kanjur, by Tadeusz Skorupski (Bruce Cameron Hall) 156 3. Early Buddhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study of the Founders' Authority, the Community, and the Discipline, by Chai-Shin Yu (Vijitha Rajapakse) 162 4. -

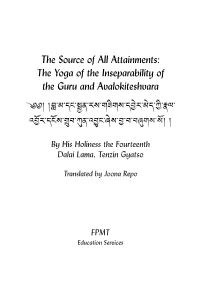

The Yoga of the Inseparability of the Guru and Avalokiteshvara

The Source of All Attainments: The Yoga of the Inseparability of the Guru and Avalokiteshvara ༄༅། །害་མ་དང་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་དབ읺ར་མ읺ད་ཀི་讣ལ་ འབ일ར་དངBy일ས་གྲུབ་ʹན་འབྱུང་ཞ His Holiness the읺ས་ Fourteenthབ་བ་བ筴གས་ས 일། ། Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso Translated by Joona Repo FPMT Education Services Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. 1632 SE 11th Avenue Portland, OR 97214 USA www.fpmt.org © 2020 Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Set in Calibri 12/15, Century Gothic, Helvetica Light, Lydian BT, and Monlam Uni Ouchan 2. Page 4, line drawing of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Artist unknown. Technical Note Italics and a small font size indicate instructions and comments found in the Tibetan text and are not for recitation. Text not presented in bold or with no indentation is likewise not for recitation. Words in square brackets have been added by the translator for clarification. For example: This is how to correctly follow the virtuous friend, [the root of the path to full enlightenment]. A Guide to Pronouncing Sanskrit The following six points will enable you to learn the pronunciation of most transliterated Sanskrit mantras found in FPMT practice texts: 1. ŚH and ṢH are pronounced similar to the “sh” in “shoe.” 2. CH is pronounced similar to the “ch” in “chat.” CHH is also similar but is more heavily aspirated. -

Chapter X Sanctuaries on Mount Penanggungan |

Chapter X Sanctuaries on Mount Penanggungan: Candi Kendalisodo, Candi Yudha, and the Panji statue from Candi Selokelir – the climax geographical situation and layout of the sanctuaries Mount Penanggungan (1,653 m), situated approximately 50 kilometres to the south of Surabaya, has a peculiar shape (fig. 10.1). It has one cen- tral peak, which is surrounded by four lower summits and four more hills on a lower level, such that it resembles a natural mandala.1 The names of the four upper hills, starting from the one in the northeast and then proceeding clockwise, are Gajah Mungkur, Kemuncup, Sarahklopo, and Bekel (fig. 10.2). Most of the 81 sanctuaries or their remains are located on the northern and western slopes of the mountain.2 Many of the sanctuaries are grouped in such a way that their loca- tions follow an ascending line on the mountain slope – for example, sites LXI, LXII, LXIV, LXVII, and LX on the western slope, starting from Candi Jolotundo (XXVII). Others are grouped together in close proxim- ity – for instance, sites I, XVI, LIV, LII, LIII, LI, L, and IL on the upper western slope. Around Gajahmungkur ten sites are grouped close to each other: VII, XX, XXI, III, XIX, IX, XXII, XVIII, VIII, and LXIX.3 As not all the buildings are dated, we cannot conclude that these arrange- ments were the result of a plan. However, the addition of new sanctuar- ies may have allowed paths of procession and groups of sanctuaries to develop gradually. These sanctuary groups and lines may correspond with the so-called mandala which are mentioned in the Nagarakertagama 1 Compare my explanations on Mount Penanggungan in Chapter IV, sub-chapter ‘Water and moun- tain’. -

Reading the History of a Tibetan Mahakala Painting: the Nyingma Chod Mandala of Legs Ldan Nagpo Aghora in the Roy Al Ontario Museum

READING THE HISTORY OF A TIBETAN MAHAKALA PAINTING: THE NYINGMA CHOD MANDALA OF LEGS LDAN NAGPO AGHORA IN THE ROY AL ONTARIO MUSEUM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Aoife Richardson, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. John C. Huntington edby Dr. Susan Huntington dvisor Graduate Program in History of Art ABSTRACT This thesis presents a detailed study of a large Tibetan painting in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) that was collected in 1921 by an Irish fur trader named George Crofts. The painting represents a mandala, a Buddhist meditational diagram, centered on a fierce protector, or dharmapala, known as Mahakala or “Great Black Time” in Sanskrit. The more specific Tibetan form depicted, called Legs Idan Nagpo Aghora, or the “Excellent Black One who is Not Terrible,” is ironically named since the deity is himself very wrathful, as indicated by his bared fangs, bulging red eyes, and flaming hair. His surrounding mandala includes over 100 subsidiary figures, many of whom are indeed as terrifying in appearance as the central figure. There are three primary parts to this study. First, I discuss how the painting came to be in the museum, including the roles played by George Croft s, the collector and Charles Trick Currelly, the museum’s director, and the historical, political, and economic factors that brought about the ROM Himalayan collection. Through this historical focus, it can be seen that the painting is in fact part of a fascinating museological story, revealing details of the formation of the museum’s Asian collections during the tumultuous early Republican era in China. -

Coloring the World: Some Thoughts from Jain and Buddhist Narratives

religions Article Coloring the World: Some Thoughts from Jain and Buddhist Narratives Phyllis Granoff Department of Religious Studies, Yale University, 451 College St, New Haven, CT 06511, USA; phyllis.granoff@yale.edu Received: 2 December 2019; Accepted: 18 December 2019; Published: 23 December 2019 Abstract: This paper begins with an examination of early Indian speculation about colors, their number, their use, and their significance. It ranges widely from the Upanis.ads to the Na¯.tya´sastra¯ , from Svet´ ambara¯ Jain canonical texts to Buddhaghosa’s treatise on meditation, the Visuddhimagga, from pura¯n. as to technical treatises on painting. It turns then to examine how select Jain and Buddhist texts used color in two important scenarios, descriptions of the setting for events and the person of the Jina/Buddha. In the concluding reflections, I compare textual practices with a few examples from the visual record to ask what role if any the colors specified in a story might have played in the choices made by an artist. Keywords: Buddhism; Jainism; color 1. Introduction1 I begin this essay with two images of Avalokite´svara,close to each other in date, a sculpture from the 11th c. in the Cleveland Museum of art, Figure1, and a folio from a 12th century manuscript of the As..tasahasrika¯ Prajñap¯ aramit¯ a¯ in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Figure2. The Cleveland image shows traces of its original paint. Both images, of very different size, in completely different media, rely on angular lines and curves to convey movement and create a rich and complex tableau. By placing them together, I wanted to suggest that the vibrancy and motion in the painting also owe much to the skillful use of color. -

Download File (Pdf; 278Kb)

SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research, Vol. 2, No. 1, Spring 2004, ISSN 1479-8484 Remarks on the Subject [of the Senbyú Pagoda at Mengún] COL. HENRY YULE, C.B. In a paper describing what I had seen of architectural remains of Hindu character in Java, which was read before the Asiatic Society of Bengal, in October, 1861, there occurred the following passage in reference to that magnificent monument of Buddhism, the Boro Bodor:— “Mr. Fergusson, who gives a good account of the Boro Bodor in his Handbook of Architecture, considers it to be a kind of representation of the great Buddhist monasteries, which are described in the Ceylonese writings as having been many stories high, and as containing hundreds of cells for monks. Sat-Mehal Prásáda In Tennent's Ceylon (vol. ii. p. 588) there is a woodcut of a singular pyramidal building at Pollanarua, called the Sat-mehal Prásáda, or ‘Seven Storied House,' which in a rough way is quite analogous to the Boro Bodor. “But the structure nearest to it in general design, that I have seen or heard of, was one visited by Mr. Oldham and me in 1855, at Mengún, above Amarapúra. It was thus described from my journal:— “ 'Further north there is an older Pagoda of very peculiar character. The basement which formed the bulk of the structure consisted of seven concentric circular terraces, each with a parapet of a curious serpentine form. These parapets rose one above and within the other like the (seven) walls of Ecbatana described by Herodotus. ... In the parapet of every terrace were at intervals niches looking outwards, in which were figures of Náts1 and warders in white marble, of half life size. -

A Practice of Consciousness Transference Involving Amitabha

A Practice of Consciousness Transference Involving Amitabha (The Gateway to Sukhavati) by The Fifth Dalai Lama (1617-1682) Limited edition for individual practice NAMO GURU MAÑJUSHRIYE The Last Turning: The third major I will unfold this method of transference teachings, which Buddha Shakyamuni To the blissful pure land— gave at Vashali. A tradition to use sleep skillfully as meditation— Described in the Prayer of Samantabhadra, Taken from the essence of the greater part Of the Last Turning. Concerning this, it also says in the Prayer of Samantabhadra, “When I am about to die…” The following explains what is meant by the above lines which were conferred by great Manjushri on Acharya Jitari. It is a profound dharma, a guideline from the great mountain of lineages, passed down in a truly unbroken line. There are four sections: 1. Preparation 2. The actual practice 3. The conclusion 4. The benefits Preparation As the great Sakya translator Jamyang Gyaltsan said: Go for refuge to the Three Jewels And then meditate on the bodhi-mind Meditate on Amitabha before you. And offer prostrations to him. This means: To purify sin through Amitabha Buddha, the yogin who wishes to be born in the pure realm of Sukhavati should clean his room and set up a painting with Sukhavati in the background, or if this is unavailable, place either a drawing or a model of Amitabha facing towards the east. Set out whatever offerings have been prepared. Then lie on your right side on a comfortable bed, facing these. Just as you are about to drop off to sleep lying on your right side, turn your head to the west. -

Candi Space and Landscape: a Study on the Distribution, Orientation and Spatial Organization of Central Javanese Temple Remains

Candi Space and Landscape: A Study on the Distribution, Orientation and Spatial Organization of Central Javanese Temple Remains Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus Prof. mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 6 mei 2009 klokke 13.45 uur door Véronique Myriam Yvonne Degroot geboren te Charleroi (België) in 1972 Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. dr. B. Arps Co-promotor: Dr. M.J. Klokke Referent: Dr. J. Miksic, National University of Singapore. Overige leden: Prof. dr. C.L. Hofman Prof. dr. A. Griffiths, École Française d’Extrême-Orient, Paris. Prof. dr. J.A. Silk The realisation of this thesis was supported and enabled by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), the Gonda Foundation (KNAW) and the Research School of Asian, African and Amerindian Studies (CNWS), Leiden University. Acknowledgements My wish to research the relationship between Ancient Javanese architecture and its natural environment is probably born in 1993. That summer, I made a trip to Indonesia to complete the writing of my BA dissertation. There, on the upper slopes of the ever-clouded Ungaran volcano, looking at the sulfurous spring that runs between the shrines of Gedong Songo, I experienced the genius loci of Central Javanese architects. After my BA, I did many things and had many jobs, not all of them being archaeology-related. Nevertheless, when I finally arrived in Leiden to enroll as a PhD student, the subject naturally imposed itself upon me. Here is the result, a thesis exploring the notion of space in ancient Central Java, from the lay-out of the temple plan to the interrelationship between built and natural landscape. -

Amitabha Phowa Lty A4.5 Jul01.P65

Amitabha Phowa 1 Amitabha Phowa Composed by Lama Thubten Yeshe 2 Amitabha Phowa Amitabha Phowa 3 Amitabha Phowa Contained herein is the technical method for transferring the consciousness to Guru Buddha Amitabha’s Pristine Realm. Preliminaries Clean the place of meditation, set up an image of Amitabha, make many offerings, and face west (or visualize that you are doing so). Refuge and Bodhichitta Motivation Take refuge in the Triple Gem and generate a bodhichitta motivation while reciting the follow- ing prayer with single-pointed concentration and devotion. I go for refuge until I am enlightened To the Buddha, the Dharma, and the supreme assembly. By my merit of giving and other perfections, May I become a buddha to benefit all sentient beings. (3x) Sang gyä chhö dang tshog kyi chhog nam la Jang chhub bar du dag ni kyab su chhi Dag gi jin sog gyi päi sö nam kyi Dro la phän chhir sang gyä drub par shog (3x) Amitabha Buddha Artist unknown. The Four Immeasurable Thoughts May all sentient beings have happiness and its cause. May all sentient beings be free of suffering and its cause. May all sentient beings attain that happiness without limits. May all sentient beings be free of attachment and aversion, holding some close and others distant. 4 Amitabha Phowa Amitabha Phowa 5 And turn the wheel of the perfect Dharma for the sake of sentient Visualizing Guru Buddha Amitabha beings. Visualize the following with single-pointed clarity. Visualize a golden 1000-spoked wheel. Above my crown on a lotus and a moon and sun throne sits Guru Bud- I dedicate all past, present, and future merits to the dha Amitabha in the vajra pose. -

Samantabhadra Prayer

Samantabhadra Prayer Homage to the ever-youthful exalted Manjushri! With purity of body, speech, and mind, I bow to all the heroic Buddhas of the past, present, and future without exception in every world in all the ten directions. By the power of this Aspiration of Samantabhadra, I bow with as many bodies as there are atoms in the Pure Lands to all those victorious Buddhas manifest in my mind, and I pay homage to all of them. I conceive the entire realm of truth to be completely filled with Enlightened Ones. On each atom I imagine there to be as many Buddhas as atoms in the Pure Lands, each Buddha surrounded by many Bodhisattvas. I honor all these blissful lords, praising their perfections with all the sounds of an ocean of varied melodies, an ocean of endless praise. I offer to those heroic Buddhas the finest flowers, garlands, music, and ointments, excellent canopies, choice lamps, and the best incense. I offer as well to those Victorious Ones the finest array of all excellent things, the finest robes and fragrances, and heaps of sweet smelling powders as high as Mount Meru. By the power of my faith in the deeds of Samantabhadra, I prostrate and present vast and unequalled offerings to each of the victorious Buddhas. I confess every type of wrong that I have done in thought, word, or deed, under the influence of desire, anger, or ignorance. I rejoice in the meritorious deeds of all the Buddhas of the ten directions, the Bodhisattvas, Pratyeka Buddhas, Arhats, practitioners, and all sentient beings.