Coloring the World: Some Thoughts from Jain and Buddhist Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Knitting Pattern Lion Brandоаlionоаsuede Desert Poncho

Free Knitting Pattern Lion Brand® Lion® Suede Desert Poncho Pattern Number: 40607 Free Knitting Pattern from Lion Brand Yarn Lion Brand® Lion® Suede Desert Poncho Pattern Number: 40607 SKILL LEVEL: Intermediate (Level 3) SIZE: Small, Medium, Large Width 10 (10½, 11)" [25.5 (26.5, 28) cm] at neck; 60 ½ (64, 68½)" [153.5 (162.5, 174) cm] at lower edge Length 23 (25½, 28)" [58.5 (65, 71) cm] at sides; 30 (32 ½, 35)" [76 (82.5, 89) cm] at points Note: Pattern is written for smallest size with changes for larger sizes in parentheses. When only one number is given, it applies to all sizes. To follow pattern more easily, circle all numbers pertaining to your size before beginning. CORRECTIONS: None as of Jun 30, 2016. To check for later updates, click here. MATERIALS • 210126 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Coffee 6 (6, 7) Balls (A) • 210125 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Mocha *Lion® Suede (Article #210). 100% Polyester; package size: Solids: 3.00 3 (4, 4) Balls (B) oz./85g; 122 yd/110m balls • 210098 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Ecru Prints: 3:00 oz/85g; 111 yd/100m balls 3 (4, 4) Balls (C) • Lion Brand Crochet Hook Size H8 (5 mm) • Lion Brand Split Ring Stitch Markers • Additional Materials • Size 8 [5 mm] 24" [60 cm] circular needles • Size 8 [5 mm] 40" [100 cm] circular needles or size needed to obtain gauge • Size 6 [4 mm] 16" [40 cm] circular needles GAUGE: 14 sts + 23 rnds = 4" [10 cm] in Stockinette st (knit every rnd) on larger needle. -

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (Revised 3/15/19)

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (revised 3/15/19) Every effort will be made to update this list on a seasonal basis. List subject to change without notice due to ongoing Zoo improvements or animal care. North American Wetlands: Muted Swans Mallard Duck Wild Turkey (off Exhibit) Egyptian Goose American White pelican (located in flamingo exhibit during winter months) Bald Eagle Wild Way Trail: (seasonal) Red-necked wallaby Prehensile tail porcupine Ring-tailed lemur Howler Monkey Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Red’s Hobby Farm: Domestic goats Domestic sheep Chickens Pied Crow Common Barn Owl Budgerigar (seasonal) Bali Mynah (seasonal) Crested Wood Partridge (seasonal) Nicobar Pigeon (seasonal) John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Frogs: Smokey Jungle frogs Chacoan Horned frog Tiger-legged monkey frog Vietnamese Mossy frog Mission Golden-eyed Tree frog Golden Poison dart frog American bullfrog Multiple species of poison dart frog North America: Golden Eagle North American River Otter Painted turtle Blanding’s turtle Common Map turtle Eastern Box turtle Red-eared slider Snapping turtle Canada Lynx Brown Bear Mountain Lion/Cougar Snow Leopard South America: South American tapir Crested screamer Maned Wolf Chilean Flamingo Fulvous Whistling Duck Chiloe Wigeon Ringed Teal Toco Toucan (opening in late May) White-faced Saki monkey John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Africa: Chimpanzee Lion African ground hornbill Egyptian Geese Eastern Bongo Warthog Cape Porcupine (off exhibit) Von der Decken’s hornbill (off exhibit) Forest Realm: Amur Tigers Red Panda -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

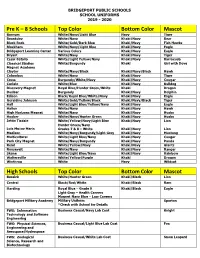

8 Schools Top Color Bottom Color Mascot

BRIDGEPORT PUBLIC SCHOOLS SCHOOL UNIFORMS 2019 - 2020 Pre K – 8 Schools Top Color Bottom Color Mascot Barnum White/Navy/Light Blue Navy Tiger Beardsley White/Navy Khaki/Navy Bear Black Rock White/Gold/Dark Blue Khaki/Navy Fish Hawks Blackham White/Navy/Light Blue Khaki/Navy Eagle Bridgeport Learning Center Various Colors Khaki/Navy Eagle Bryant White/Navy Khaki/Navy Tiger César Batalla White/Light Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Barracuda Classical Studies White/Burgundy Khaki Girl with Dove Magnet Academy Claytor White/Navy/Black Khaki/Navy/Black Hawk Columbus White/Navy Khaki/Navy Tiger Cross Burgundy/White/Navy Khaki/Navy Cougar Curiale White/Blue Khaki/Navy Bulldog Discovery Magnet Royal Blue/Hunter Green/White Khaki Dragon Dunbar Burgundy Khaki/Navy Dolphin Edison Black/Royal Blue/White/Navy Khaki/Navy Eagle Geraldine Johnson White/Gold/Yellow/Black Khaki/Navy/Black Tiger Hall White/Light Blue/Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Eagle Hallen White/Navy Khaki/Navy Hawk High Horizons Magnet White/Navy Khaki/Navy Husky Hooker White/Navy/Hunter Green Khaki/Navy Husky Jettie Tisdale White/Yellow/Navy/Light Blue Khaki/Navy Lion Hunter Green/Navy Luis Muñoz Marín Grades 7 & 8 – White Khaki/Navy Lion Madison White/Navy/Burgundy/Light Grey Khaki/Navy Mustang Multicultural White/Light Blue/Navy Khaki/Navy Cougar Park City Magnet White/Navy/Burgundy Khaki/Navy Panda Read White/Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Giants Roosevelt White/Navy Khaki/Navy Ranger Skane White/Light Blue/Navy Khaki/Navy Rainbow Waltersville White/Yellow/Purple Khaki Dragon Winthrop White Navy Wildcat -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Colours in Nature Colours

Nature's Wonderful Colours Magdalena KonečnáMagdalena Sedláčková • Jana • Štěpánka Sekaninová Nature is teeming with incredible colours. But have you ever wondered how the colours green, yellow, pink or blue might taste or smell? What could they sound like? Or what would they feel like if you touched them? Nature’s colours are so wonderful ColoursIN NATURE and diverse they inspired people to use the names of plants, animals and minerals when labelling all the nuances. Join us on Magdalena Konečná • Jana Sedláčková • Štěpánka Sekaninová a journey to discover the twelve most well-known colours and their shades. You will learn that the colours and elements you find in nature are often closely connected. Will you be able to find all the links in each chapter? Last but not least, if you are an aspiring artist, take our course at the end of the book and you’ll be able to paint as exquisitely as nature itself does! COLOURS IN NATURE COLOURS albatrosmedia.eu b4u publishing Prelude Who painted the trees green? Well, Nature can do this and other magic. Nature abounds in colours of all shades. Long, long ago people began to name colours for plants, animals and minerals they saw them in, so as better to tell them apart. But as time passed, ever more plants, animals and minerals were discovered that reminded us of colours already named. So we started to use the names for shades we already knew to name these new natural elements. What are these names? Join us as we look at beautiful colour shades one by one – from snow white, through canary yellow, ruby red, forget-me-not blue and moss green to the blackest black, dark as the night sky. -

Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-08-17 Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography Ereshefsky, Joshua Ian Ereshefsky, J. I. (2020). Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112477 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Tracing Buddhist Responses to the Crisis of Cosmography by Joshua Ian Ereshefsky A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA AUGUST, 2020 © Joshua Ian Ereshefsky 2020 i ABSTRACT Buddhists, across different schools and regions, traditionally posited a similar world model—one that is flat and centered by giant Mount Meru. This world model is chiefly featured in Vasubandhu’s fourth century CE text, the Abhidharmakośabhāṣyam. In 1552, Christian missionary Francis Xavier introduced European spherical-world cosmography to Japan, precipitating what this thesis terms the Buddhist -

Symbolism of the Buddhist Stūpa

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Gregory Schopen Roger Jackson Indiana University Fairfield University Bloomington, Indiana, USA Fairfield, Connecticut, USA EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Bardxvell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfteld, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Bruce Cameron Hall College of William and Mary Williamsburg, Virginia, USA Volume 9 1986 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. Signs, Memory and History: A Tantric Buddhist Theory of Scriptural Transmission, by Janet Gyatso 7 2. Symbolism of the Buddhist Stupa, by Gerard Fussman 37 3. The Identification of dGa' rab rdo rje, by A. W. Hanson-Barber 5 5 4. An Approach to Dogen's Dialectical Thinking and Method of Instantiation, by Shohei Ichimura 65 5. A Report on Religious Activity in Central Tibet, October, 1985, by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. and Cyrus Stearns 101 6. A Study of the Earliest Garbha Vidhi of the Shingon Sect, by Dale Allen Todaro 109 7. On the Sources for Sa skya Panclita's Notes on the "bSam yas Debate," by Leonard W.J. van der Kuijp 147 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. The Bodymind Experience in Japanese Buddhism: A Phenomenological Study ofKukai and Dogen, by D. Shaner (William Waldron) 155 2. A Catalogue of the s Tog Palace Kanjur, by Tadeusz Skorupski (Bruce Cameron Hall) 156 3. Early Buddhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study of the Founders' Authority, the Community, and the Discipline, by Chai-Shin Yu (Vijitha Rajapakse) 162 4. -

Whats Heaven Pdf Free Download

WHATS HEAVEN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maria Shriver,Sandra Speidel | 32 pages | 01 Nov 2007 | St Martin's Press | 9780312382414 | English | New York, United States Whats Heaven PDF Book How that he was caught up into paradise, and heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter. First, the message of the kingdom of heaven is a genuine offer from God to rule in the hearts of those who believe in His name. We were made to live forever somewhere. The old body is …. The ruler of China in every Chinese dynasty would perform annual sacrificial rituals to heaven, usually by slaughtering two healthy bulls as a sacrifice. In the 19th century book Legends of the Jews , rabbi Louis Ginzberg compiled Jewish legends found in rabbinic literature. So just as Jesus was able to materialize or dematerialize at will, due to the nature of His new celestial body, so too will we! Under the old covenant no one could come near God except under very strict conditions. Heaven and earth, as personified powers of nature and thus worthy of worship, are evidently not of equal age. Not everyone is in heaven now. The first instance of this was His initial Resurrection. For other uses, see Heaven disambiguation. An Elementary Study of Islam. In heaven there will be no strangers. What is Blasphemy and Why is it So Deadly? Revelation of The Antichrist. And this state of grace is determined by both the gift of God and the degree to which the blessed cooperated with that grace during his earthly sojourn. -

Skanda Sashti Approaching the Lord of Illumination

folio line HOLY DAYS THAT AMERICA’S HINDUS CELEBRATE s. rajam Skanda Sashti Approaching the Lord of Illumination the fi ghting rooster. Devotees pilgrimage to kanda Sashti is a six-day South Indian festival to Skanda, the Murugan’s temples, especially the temple in Lanham, Maryland, and the seaside sanctuary Lord of Religious Striving, also known as Murugan or Karttikeya. at Tiru chendur in South India. SIt begins on the day after the new moon in the month of Karttika (October/November) with chariot processions and pujas invoking His What is the legend of Skanda Sashti? protection and grace. The festival honors Skanda’s receiving His lance, It is said that eons ago, Skanda fought a power- ful asura, or demon, named Surapadman, who or vel, of spiritual illumination, and culminates in a victory celebration embodied the forces of selfi shness, ignorance, of spiritual light over darkness on the fi nal day. Penance, austerity, fast- greed and chaos. Skanda defeated and mas- tered those lower forces, which He uses, to this ing and devout worship are especially fruitful during this sacred time. sitaraman soumya day, to the greater good. The subdued demon became his faithful servant, the proud and Who is Skanda? broken, families enjoy a sweet pudding called beautiful peacock on which Skanda rides. Kesari Skanda is a God of many attributes, often payasam along with fried delicacies. A six- This quick and easy sweet semolina- depicted as six-faced and twelve-armed. part prayer for protection, called the Skanda What happens on the sixth day? based dish gets its name from kesar, or Saivite Hindus hail this supreme warrior, the Sashti Kavacham, is chanted. -

On the Kama-Loka and Devachan

The Soul's Journey through Life and Death – Part 4 Excerpts from: Key to Theosophy On The Kama-Loka and Devachan On The Fate of the Lower "Principles" ENQUIRER. You spoke of Kama-loka, what is it? THEOSOPHIST. When the man dies, his lower three principles leave him forever; i.e., body, life, and the vehicle of the latter, the astral body or the double of the living man. And then, his four principles — the central or middle principle, the animal soul or Kama- rūpa, with what it has assimilated from the lower Manas, and the higher triad find themselves in Kama-loka. The latter is an astral locality1, the limbus2 of scholastic theology, the Hades3 of the ancients, and, strictly speaking, a locality only in a relative sense. It has neither a definite area nor boundary, but exists within subjective space; i.e., is beyond our sensuous perceptions. Still it exists, and it is there that the astral eidolons4 of all the beings that have lived, animals included, await their second death. For the animals it comes with the disintegration and the entire fading out of their astral particles to the last. For the human eidolon it begins when the Ātma-Buddhi-Manasic triad is said to "separate" itself from its lower principles, or the reflection of the ex-personality, by falling into the Devachanic state. 1 Locality - The fact or quality of having position in space. 2 Limbus - (Latin. for "edge," "fringe," e.g. of a garment), a theological term denoting the border of hell, where dwell those who, while not condemned to torture, yet are deprived of the joy of heaven. -

Theosophical Articles and Notes

THEOSOPHICAL ARTICLES AND NOTES Reprinted from Original Sources THE THEOSOPHY CO. Los Angeles 1985 ISBN 0-938998-29-3 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Scanned & edited by volunteers at the United Lodge of Theosophists, London, UK. Edited Oct 2020 & April 2021 FOREWORD The articles in this volume come from a variety of sources. They are presented here for their intrinsic worth to students of Theosophy. They are grouped according to the place of first appearance —in the Theosophist, Lucifer, the Path, and other sources. Within these groupings they are arranged chronologically. Internal evidence strongly suggests that some of them have an “adept” origin, and they are so presented. One or two articles unintentionally omitted from Theosophical Articles by H.P.B. and W.Q.J. are included. Other contributions, not identified as to author, are of a quality which makes it appropriate to reprint them here. Thus there are articles, replies and notes which appeared in the Theosophist and Lucifer, also material by Damodar K. Mavalankar, and two articles signed “Murdhna Joti” from the Path. Cicero’s “Vision of Scipio” is included by reason of H.P.B.’s briefly informative footnotes. Judge’s “Notes on the Bhagavad Gita” is a Path article which was not a part of the book of that name. Finally, there is material taken from A.P. Sinnett’s The Occult World, from the notes of Robert Bowen, a pupil of H.P.B., and also from notes found in the effects of Countess Wachtmeister, apparently taken down from dictation by H.P.B.