Art. XIV.— Buddhist Saint Worship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Dr. Devala Rao Garikapati C.V CURRICULUM-VITAE Dr. Devala

Dr. Devala Rao Garikapati C.V CURRICULUM-VITAE Dr. Devala Rao Garikapati M.Pharm, Ph.D., F.I.C. FABAP Professor& Principal H.No. 2-99/1, Kottevari St., 3rd Cross, Ramavarappadu – 521 108 Vijayawada Rural,Amaravati Krishna (Dist), Andhra Pradesh, India Professor of Pharmaceutical Analysis Principal K.V.S.R. Siddhartha college of Pharmaceutical Sciences Siddhartha Nagar, Pinnamaneni Polyclinic Road, [email protected] Vijayawada – 520 010 Fourth February 1964 A.P., India Phone (D) : 0866-2479775, 2493347 Mobile : 098488-27872 Education _____________________________________________________________ Degree Institution & University Division Year _____________________________________________________________ Ph.D Gandhigram Rural -- 2003 Institute – DU, Gandhigram, TN. _____________________________________________________________ M.Pharm Department of Pharmaceutical First and 1989 Sciences, Winner of Andhra University Prof. Viswanadham’s Visakhapatnam Gold medal _____________________________________________________________ B.Pharm Department of First and 1987 Pharmaceutical Sciences AU 2nd Visakhapatnam Rank Holder _____________________________________________________________ F.I.C. Institute of Chemists (India), -- 2005 Kolkata _____________________________________________________________ FABAP Association of Biotechnology -- 2007 And Pharmacy, ANU _____________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________ Academic Experience: December 2004 to till date Professor & Principal, -

Whats Heaven Pdf Free Download

WHATS HEAVEN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maria Shriver,Sandra Speidel | 32 pages | 01 Nov 2007 | St Martin's Press | 9780312382414 | English | New York, United States Whats Heaven PDF Book How that he was caught up into paradise, and heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter. First, the message of the kingdom of heaven is a genuine offer from God to rule in the hearts of those who believe in His name. We were made to live forever somewhere. The old body is …. The ruler of China in every Chinese dynasty would perform annual sacrificial rituals to heaven, usually by slaughtering two healthy bulls as a sacrifice. In the 19th century book Legends of the Jews , rabbi Louis Ginzberg compiled Jewish legends found in rabbinic literature. So just as Jesus was able to materialize or dematerialize at will, due to the nature of His new celestial body, so too will we! Under the old covenant no one could come near God except under very strict conditions. Heaven and earth, as personified powers of nature and thus worthy of worship, are evidently not of equal age. Not everyone is in heaven now. The first instance of this was His initial Resurrection. For other uses, see Heaven disambiguation. An Elementary Study of Islam. In heaven there will be no strangers. What is Blasphemy and Why is it So Deadly? Revelation of The Antichrist. And this state of grace is determined by both the gift of God and the degree to which the blessed cooperated with that grace during his earthly sojourn. -

On the Kama-Loka and Devachan

The Soul's Journey through Life and Death – Part 4 Excerpts from: Key to Theosophy On The Kama-Loka and Devachan On The Fate of the Lower "Principles" ENQUIRER. You spoke of Kama-loka, what is it? THEOSOPHIST. When the man dies, his lower three principles leave him forever; i.e., body, life, and the vehicle of the latter, the astral body or the double of the living man. And then, his four principles — the central or middle principle, the animal soul or Kama- rūpa, with what it has assimilated from the lower Manas, and the higher triad find themselves in Kama-loka. The latter is an astral locality1, the limbus2 of scholastic theology, the Hades3 of the ancients, and, strictly speaking, a locality only in a relative sense. It has neither a definite area nor boundary, but exists within subjective space; i.e., is beyond our sensuous perceptions. Still it exists, and it is there that the astral eidolons4 of all the beings that have lived, animals included, await their second death. For the animals it comes with the disintegration and the entire fading out of their astral particles to the last. For the human eidolon it begins when the Ātma-Buddhi-Manasic triad is said to "separate" itself from its lower principles, or the reflection of the ex-personality, by falling into the Devachanic state. 1 Locality - The fact or quality of having position in space. 2 Limbus - (Latin. for "edge," "fringe," e.g. of a garment), a theological term denoting the border of hell, where dwell those who, while not condemned to torture, yet are deprived of the joy of heaven. -

Theosophical Articles and Notes

THEOSOPHICAL ARTICLES AND NOTES Reprinted from Original Sources THE THEOSOPHY CO. Los Angeles 1985 ISBN 0-938998-29-3 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Scanned & edited by volunteers at the United Lodge of Theosophists, London, UK. Edited Oct 2020 & April 2021 FOREWORD The articles in this volume come from a variety of sources. They are presented here for their intrinsic worth to students of Theosophy. They are grouped according to the place of first appearance —in the Theosophist, Lucifer, the Path, and other sources. Within these groupings they are arranged chronologically. Internal evidence strongly suggests that some of them have an “adept” origin, and they are so presented. One or two articles unintentionally omitted from Theosophical Articles by H.P.B. and W.Q.J. are included. Other contributions, not identified as to author, are of a quality which makes it appropriate to reprint them here. Thus there are articles, replies and notes which appeared in the Theosophist and Lucifer, also material by Damodar K. Mavalankar, and two articles signed “Murdhna Joti” from the Path. Cicero’s “Vision of Scipio” is included by reason of H.P.B.’s briefly informative footnotes. Judge’s “Notes on the Bhagavad Gita” is a Path article which was not a part of the book of that name. Finally, there is material taken from A.P. Sinnett’s The Occult World, from the notes of Robert Bowen, a pupil of H.P.B., and also from notes found in the effects of Countess Wachtmeister, apparently taken down from dictation by H.P.B. -

Esoteric Buddhism by A.P

Esoteric Buddhism by A.P. Sinnett Esoteric Buddhism by A.P. Sinnett Author also of The Occult World President of the London Lodge of the Theosophical Society Fifth edition, annotated and enlarged by the author London, Chapman and Hall Ltd 1885 Page 1 Esoteric Buddhism by A.P. Sinnett CONTENTS Preface to the Annotated Edition Preface to the Original Edition CHAPTER I - Esoteric Teachers Nature of the Present Exposition - Seclusion of Eastern Knowledge - The Arhats and their Attributes - The Mahatmas - Occultists generally - Isolated Mystics - Inferior Yogis - Occult Training - The Great Purpose -Its Incidental Consequences - Present Concessions CHAPTER II - The Constitution of Man Esoteric Cosmogony - Where to Begin - Working back from Man to Universe - Analysis of Man - The Seven Principles CHAPTER III -The Planetary Chain Esoteric Views of Evolution - The Chain of Globes - Progress of Man round them - The Spiral Advance - Original Evolution of the Globes - The Lower Kingdoms CHAPTER IV -The World Periods Uniformity of Nature- Rounds and Races - The Septenary Law - Objective and Subjective Lives - Total Incarnations - Former Races on Earth - Periodic Cataclysms - Atlantis - Lemuria - The Cyclic Law CHAPTER V - Devachan Spiritual Destinies of the Ego - Karma - Division of the Principles of Death - Progress of the Higher Duad - Existence in Devachan - Subjective Progress - Avitchi - Earthly Connection with Devachan - Devachanic Periods CHAPTER VI - Kâma Loca The Astral Shell - Its Habitat - Its Nature - Surviving Impulses - Elementals - -

THE EQUINOX No

THE EQUINOX No. IV. will contain in its 400 pages VARIOUS OFFICIAL INSTRUCTIONS of the A\ A\ THE ELEMENTAL CALLS OR KEYS, WITH THE GREAT WATCH TOWERS OF THE UNI- VERSE and their explanation. A complete treatise, fully illustrated, upon the Spirits of the Elements, their names and offices, with the method of calling them forth and controlling them. With an account of the Heptarchicall Mystery. The Thirty Aethyrs or Aires with “The Vision and the Voice,” being the Cries of the Angels of the Aethyrs, a revalation of the highest truths pertaining to the grade of Magister Templi, and many other matters. Fully illustrated. THE CONTINUATION OF THE HERB DAN- GEROUS. Selection from H. G. Ludlow, “The Hashish- Eater.” MR. TODD: A Morality, by the author of “Rosa Mundi.” THE DAUGHTER OF THE HORSELEECH, by ETHEL RAMSAY. THE TEMPLE OF SOLOMON THE KING. [Continuation. FRATER P.’S EXPERIENCES IN THE EAST. A complete account of the various kinds of Yoga. DIANA OF THE INLET. By KATHERINE S. PRITCHARD. Fully Illustrated. ACROSS THE GULF: An adept’s memory of his incarnation in Egypt under the 26th dynasty; with an account of the Passing of the Equinox of Isis. &c. &c. &c Crown 8vo, Scarlet Buckram, pp. 64. This Edition strictly limited to 500 Copies. PRICE 10s A\ A\ PUBLICATION IN CLASS B. ========== BOOK 777 HIS book contains in concise tabulated form a comparative view of all the symbols of the great Treligions of the world; the perfect attributions of the Taro, so long kept secret by the Rosicrucians, are now for the first time published; also the complete secret magical correspondences of the G\ D\ and R. -

Bhagavad Gita Free

öËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | é∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú-æËíŸæ “ Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ úŸ≤¤™‰ ™ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | éÂ∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ 韺Π∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº ∫Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿ §-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | -⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿ËßThe‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%Bhagavad‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å Gita || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸ {Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤ æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’ ≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘ ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥The˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸº OriginalÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅSanskrit é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰ —ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ “‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºand Î ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸº Å Ç—™‹ ™—ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿ Ÿ ∏“‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§- An English Translation ≤Ÿ¨Ÿæ -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought. -

The Ocean of Theosophy

of An Introduction to the writings of H. P. Blavatsky Outlines the broad scope and principles of Theosophy William Q. Judge In the early s William Q. Judge recognized the need for a literature on theosophy that could be readily under- stood by all. He responded with a series of newspaper articles that were soon published in book form as The Ocean of Theosophy. Providing a concise yet comprehensive survey of the basic teach- ings, it clarifies such topics as reincar- nation and karma; the sevenfold nature of man, earth, and the universe; after- death states and cyclic evolution; sages, adepts, and the world’s religions; psy- chic phenomena, spiritualism, the pitfalls of pseudo-occultism; and many more. Here is knowledge based upon evidence and experience, written with brevity and depth. W Q. J was born in Dublin, Ireland, on April , . His family emi- grated in to New York where he specialized in corporate law (New York State Bar, ). A co-founder with H. P. Blavatsky and Henry S. Olcott of the Theosophical Society in , he later became General Secretary of its American Section and Vice President of the international Society. Writing and lecturing from coast to coast, he made theosophy known and respected throughout America. He died in New York City on March , Cover Design: Patrice Hughes In the Author’s Words . Just as the ancients taught, so does Theosophy: that the course of evolution is the drama of the soul and that Nature exists for no other purpose than the soul’s experience. The Theosophist agrees with Professor Huxley in the assertion that there must be beings in the universe whose intelligence is as much beyond ours as ours exceeds that of the black beetle, and who take an active part in the government of the natural order of things. -

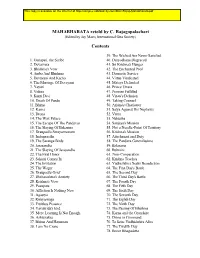

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Vedic Period Language and Literature

Study of Vedic Period Language and Literature Prem Nagar Overview Introduction to the Vedas Vedic Language Characteristics of the Vedic Language Vedic Literature Contents of the Vedic Literature Retention of the Vedic Literature Vedic Period: Language and Literature 2 Introduction to the Veda (वेद) Vedas are believed to be the earliest literary composition of the world! Text and Contents: • They are scriptural poetic narratives of undetermined age containing prayers, philosophical dialogue, myth, ritual chants and invocation. • They helped develop ritualistic procedures, social organization and an ethical code of conduct. • The language and grammar appear local in origin. Transmission: • Composition in chhandas (छ�:, meters) helped transmission over time. Lasting Impact • Prayers and rituals are used for atonement and to alleviate grief. • Philosophy and prescribed belief systems provided a foundation for culture in India. Vedic Period: Language and Literature 3 What is Veda (वेद) • Word Veda (वेद) signifies knowledge, traditionally considered eternal. • The Vedas were handed down orally and are called śruti (श्रुित) literature: Rig-Veda (ऋ�ेद ) (RV) - Hymns of Praise (recitation) Sama-Veda (सामवेद) (SV) - Knowledge of the Melodies Yajur-Veda (यजुव�द) (YV) - Sacrificial rituals for liturgy Atharva-Veda (अथव�वेद) (AV) - Formulas • They fall into four classes of literary works: Samhitås (संिहता): rule-based verses (collection of hymns) Aranyakas (आर�क): developed beliefs (theological explanation) Brāhmaṇa (ब्रा�णम्): explanations of rituals (ceremonies, sacrifices) Upanishads (उपिनषद् ): philosophy that has Vedic essence • The Rig-Veda Samhitås are organized into: 1. Mandalas (म�ल, books) consisting of hymns called sūkta 2. Sūktas (सू�) consist of individual ṛcs (stanzas) 3.