Buddhism and Vedanta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concise Ancient History of Indonesia.Pdf

CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INDONESIA CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY O F INDONESIA BY SATYAWATI SULEIMAN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION JAKARTA Copyright by The Archaeological Foundation ]or The National Archaeological Institute 1974 Sponsored by The Ford Foundation Printed by Djambatan — Jakarta Percetakan Endang CONTENTS Preface • • VI I. The Prehistory of Indonesia 1 Early man ; The Foodgathering Stage or Palaeolithic ; The Developed Stage of Foodgathering or Epi-Palaeo- lithic ; The Foodproducing Stage or Neolithic ; The Stage of Craftsmanship or The Early Metal Stage. II. The first contacts with Hinduism and Buddhism 10 III. The first inscriptions 14 IV. Sumatra — The rise of Srivijaya 16 V. Sanjayas and Shailendras 19 VI. Shailendras in Sumatra • •.. 23 VII. Java from 860 A.D. to the 12th century • • 27 VIII. Singhasari • • 30 IX. Majapahit 33 X. The Nusantara : The other islands 38 West Java ; Bali ; Sumatra ; Kalimantan. Bibliography 52 V PREFACE This book is intended to serve as a framework for the ancient history of Indonesia in a concise form. Published for the first time more than a decade ago as a booklet in a modest cyclostyled shape by the Cultural Department of the Indonesian Embassy in India, it has been revised several times in Jakarta in the same form to keep up to date with new discoveries and current theories. Since it seemed to have filled a need felt by foreigners as well as Indonesians to obtain an elementary knowledge of Indonesia's past, it has been thought wise to publish it now in a printed form with the aim to reach a larger public than before. -

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

Implicit Science in Hindu Thought Varadaraja V

Science, Technology, and Religion V Implicit Science in Hindu Thought Varadaraja V. Raman One can find apologists from all the major religions who aim to bolster the standings of their faith by proclaiming its confluence with science. Some have even gone so far as to argue that their ancient scriptures and doctrines presage specific ideas and findings of modern science. As Imad-ad-Dean Ahmad and Martin J. Verhoeven show elsewhere in this symposium, this is a growing trend among some scholars of Islam and Buddhism. But it is also a perennial presence in the great religious tradi- tions of Judaism, Christianity, and Hinduism. From a scientific point of view these claims are untenable, as the find- ings of modern science spring from observations, insights, instruments, philosophical outlooks, and knowledge that were absent in the ancient world. But the defenders of these claims contend that the philosophers and prophets of distant ages had other means of knowing than logic, differential equations, and the spectrometer — that the scientific insights in scripture are a testament to their divine origin. Though perhaps well-meaning, such claims essentially belong to pseudoscience, not least because they are typically based more on parochialism and questionable hermeneutics than on serious scholarship. But this does not mean that the search for areas of genuine harmony between science and scripture is always misguided. There is no solid evidence that ancient prophets or religious thinkers were privy to any revealed knowledge of scientific findings in advance of their peers. But ancient thinkers did articulate many of the broad possibilities for answers to major questions that have since been, in a sense, adjudicated by science. -

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

Upanishad Vahinis

Glossary This glossary contains Sanskrit words, people, places, and literature that appear in Upanishad Vahini. Some Sanskrit words have made their way into English and appear in English dictionaries. A few of them are used without definition in the text, but they are defined in this glossary. Among them areAtma , dharma, guru, karma, yogas, and yogi. The text uses standard spellings for Sanskrit, and this glossary provides the same spellings. But some of the Sanskrit compounds have been hyphenated between their constituent words to aid those who want to analyze the meanings of individual words. When compound words are broken, individual words are given. Aagama. That which has come or originated. The primeval source of knowledge. A name for Vedas. aapo-jyoti. Splendour of water. abhasa. Appearance, superimposition of false over real. a-bhaya. Fearlessness. a-chetana. Non-intelligent, unconscious, inert, senseless. a-dharma. Evil, unjustice. adhyasa. Superimposition. adi-atma. Pertaining to the individual soul, spirit, or manifestation of supreme Brahman. adi-atmic. Pertaining to adi-atma. adi-bhauthika. Pertaining to the physical or material world; the fine spiritual aspect of material objects. adi-daivika. Pertaining to divinity or fate, e.g. natural disasters. aditya. Sun. Aditya. Son of Aditi; there were twelve of them, one of them being Surya, the sun, so Surya is sometimes called Aditya. a-dwaitha. Nondualism or monism, the Vedantic doctrine that everything is God. a-dwaithic. Of or pertaining to a-dwaitha. agni. Fire element. Agni. God of fire. Agni-Brahmana. Another word for the Section on horse sacrifice. agnihotra. Ritual of offering oblations in the holy fireplace. -

18 Phases Or Realms

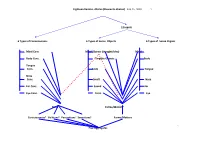

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

Jesus-Buddha-Krishna: Still Present?

JESUS-BUDDHA-KRISHNA: STILL PRESENT? Paul F. Knitter PRECIS The intent of this article is to elaborate a moie adequate understanding of the presence of Christ in Word and Sacrament, which will then make possible a more productive dialogue with Hinduism and Buddhism. Foundational to this investigation is contemporary theol ogy's understanding of symbol-myth. First it is shown how, on the basis of what is being said about myth and symbol, the real presence of Christ in the Christian community can be understood meaningfully and coherently as a mythic-symbolic presence. This refocuses the problem of the relation between the historical Jesus and the Christ of faith. It means that Christianity must move beyond "historicism"-the attitude that equates the real with the factual. More precisely, it implies that the experience of salvation is not mediated through historical events in themselves but insofar as they are "mythified": symbols save; historical events (as events) do not Christianity therefore can be said to be based on "mythistory," not just history. Various objections to this apparent mythification of Christianity are considered; the abiding importance of the historical Jesus is maintained. Such an esteem for the mythic Christ requires Christians to modify their claim that Christianity's uniqueness is based on its historicity. More precisely, Christians are called upon to recognize the real and salvific presence of the mythic Buddha and the mythic Krishna (and other Avatars) to their followers. Particular significance is given to the process in which Gautama-not unlike Jesus-was glorified and mythified after death. Christ is always present in His Church, especially in her liturgical celebration. -

Com 23 Draft B

Community Issue 23 - Page 1 Autumn 2005 / 2548 The Upāsaka & Upāsikā Newsletter Issue No. 23 Dagoba at Mahintale Dagoba InIn thisthis issue.......issue....... InIn peoplepeople wewe trusttrust ?? TheThe Temple at Kosgoda The wisdom of the heartheart SicknessSickness——A Teacher AssistedAssisted DyingDying MakingMaking connectionsconnections beyond words BluebellBluebell WalkWalk Community Community Issue 23 - Page 2 In people we trust? Multiculturalism and community relations have been This is a thoroughly uncomfortable position to be in, as much in the news over recent months. The tragedy of anyone who has suffered from arbitrary discrimination can the London bombings and the spotlight this has attest. There is a feeling of helplessness that whatever one thrown on to what is called ‘the Moslem community’ says or does will be misinterpreted. There is a resentment has led me to reflect upon our own Buddhist that one is being treated unfairly. Actions that would pre- ‘community’. Interestingly, the name of this newslet- viously have been taken at face value are now suspected of ter is ‘Community’, and this was chosen in discussion having a hidden agenda in support of one’s group. In this between a number of us, because it reflected our wish situation, rumour and gossip tend to flourish, and attempts to create a supportive and inclusive network of Forest to adopt a more inclusive position may be regarded with Sangha Buddhist practitioners. suspicion, or misinterpreted to fit the stereotype. The AUA is predominantly supported by western Once a community has polarised, it can take a great deal converts to Buddhism. Some of those who frequent of work to re-establish trust. -

The Vedanta of Ramanuja

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Philosophy & Comparative Religion Department Faculty Publications Philosophy & Comparative Religion Department 2016 Review of Indian Thought and Western Theism: The Vedanta of Ramanuja Sucharita Adluri Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clphil_facpub Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Original Citation Adluri, S. (2016). Review of Martin Ganeri's Indian Thought and Western Theism: The Vedanta of Ramanuja, Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies, 29, 77-9. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy & Comparative Religion Department at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy & Comparative Religion Department Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 29 God and Evil in Hindu and Christian Article 14 Theology, Myth, and Practice 2016 Book Review: Indian Thought and Western Theism: the Vedan̄ ta of Ram̄ an̄ uja Sucharita Adluri Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Adluri, Sucharita (2016) "Book Review: Indian Thought and Western Theism: the Vedan̄ ta of Ram̄ an̄ uja," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 29, Article 14. -

Upanishad Vahinis

Upanishad Vahini Stream of The Upanishads SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Upanishad Vahini 7 DEAR READER! 8 Preface for this Edition 9 Chapter I. The Upanishads 10 Study the Upanishads for higher spiritual wisdom 10 Develop purity of consciousness, moral awareness, and spiritual discrimination 11 Upanishads are the whisperings of God 11 God is the prophet of the universal spirituality of the Upanishads 13 Chapter II. Isavasya Upanishad 14 The spread of the Vedic wisdom 14 Renunciation is the pathway to liberation 14 Work without the desire for its fruits 15 See the Supreme Self in all beings and all beings in the Self 15 Renunciation leads to self-realization 16 To escape the cycle of birth-death, contemplate on Cosmic Divinity 16 Chapter III. Katha Upanishad 17 Nachiketas seeks everlasting Self-knowledge 17 Yama teaches Nachiketas the Atmic wisdom 18 The highest truth can be realised by all 18 The Atma is beyond the senses 18 Cut the tree of worldly illusion 19 The secret: learn and practise the singular Omkara 20 Chapter IV. Mundaka Upanishad 21 The transcendent and immanent aspects of Supreme Reality 21 Brahman is both the material and the instrumental cause of the world 21 Perform individual duties as well as public service activities 22 Om is the arrow and Brahman the target 22 Brahman is beyond rituals or asceticism 23 Chapter V. Mandukya Upanishad 24 The waking, dream, and sleep states are appearances imposed on the Atma 24 Transcend the mind and senses: Thuriya 24 AUM is the symbol of the Supreme Atmic Principle 24 Brahman is the cause of all causes, never an effect 25 Non-dualism is the Highest Truth 25 Attain the no-mind state with non-attachment and discrimination 26 Transcend all agitations and attachments 26 Cause-effect nexus is delusory ignorance 26 Transcend pulsating consciousness, which is the cause of creation 27 Chapter VI. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad).