Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Unravelling of the Dharma-Dharmat- Vibhga-Vrtti of Vasubandhu

An unravelling of the Dharma-dharmat- vibhga-vrtti of Vasubandhu Autor(en): Anacker, Stefan Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 46 (1992) Heft 1: Études bouddhiques offertes à Jacques May PDF erstellt am: 28.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-146946 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst -

Thinking in Buddhism: Nagarjuna's Middle

Thinking in Buddhism: Nagarjuna’s Middle Way 1994 Jonah Winters About this Book Any research into a school of thought whose texts are in a foreign language encounters certain difficulties in deciding which words to translate and which ones to leave in the original. It is all the more of an issue when the texts in question are from a language ancient and quite unlike our own. Most of the texts on which this thesis are based were written in two languages: the earliest texts of Buddhism were written in a simplified form of Sanskrit called Pali, and most Indian texts of Madhyamika were written in either classical or “hybrid” Sanskrit. Terms in these two languages are often different but recognizable, e.g. “dhamma” in Pali and “dharma” in Sanskrit. For the sake of coherency, all such terms are given in their Sanskrit form, even when that may entail changing a term when presenting a quote from Pali. Since this thesis is not intended to be a specialized research document for a select audience, terms have been translated whenever possible,even when the subtletiesof the Sanskrit term are lost in translation.In a research paper as limited as this, those subtleties are often almost irrelevant.For example, it is sufficient to translate “dharma” as either “Law” or “elements” without delving into its multiplicity of meanings in Sanskrit. Only four terms have been left consistently untranslated. “Karma” and “nirvana” are now to be found in any English dictionary, and so their translation or italicization is unnecessary. Similarly, “Buddha,” while literally a Sanskrit term meaning “awakened,” is left untranslated and unitalicized due to its titular nature and its familiarity. -

Searching for a Possibility of Buddhist Hermeneutics: Two Exegetic Strategies in Buddhist Tradition

Searching for a Possibility of Buddhist Hermeneutics: Two Exegetic Strategies in Buddhist Tradition Sumi Lee University of California, Los Angeles One of the main concerns in religious studies lies in hermeneutics 1 : While interpreters of religion, as those in all other fields, are doomed to perform their work through the process of conceptualization of their subjects, religious reality has been typically considered as transcending conceptual categorization. Such a dilemma imposed on the interpreters of religion explains the dualistic feature of the Western hermeneutic history of religion--the consistent attempts to describe and explain religious reality on the one hand and the successive reflective thinking on the limitation of human knowledge in understanding ultimate reality on the other hand.2 Especially in the modern period, along with the emergence of the methodological reflection on religious studies, the presupposition that the “universally accepted” religious reality or “objectively reasoned” religious principle is always “over there” and may be eventually disclosed through refined scientific methods has become broadly questioned and criticized. The apparent tension between the interpreter/interpretation and the object of interpretation in religious studies, however, does not seem to have undermined the traditional Buddhist exegetes’ eagerness for their work of expounding the Buddhist teachings: The Buddhist exegetes and commentators not only devised various types of systematic and elaborate literal frameworks such as logics, theories, styles and rhetoric but also left the vast corpus of canonical literatures in order to transmit their religious teaching. The Buddhist interpreters’ enthusiastic attitude in the composition of the literal works needs more attention because they were neither unaware of the difficulty of framing the religious reality into the mold of language nor forced to be complacent to the limited use of language about the reality. -

Some Reflections on Critical Buddhism

Stone on Critical Buddhism.qxd 5/14/99 5:21 PM Page 159 Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/1–2 REVIEW ARTICLE Some Reµections on Critical Buddhism Jacqueline STONE Jamie HUBBARD and Paul L. SWANSON, eds., Pruning the Bodhi Tree: The Storm over Critical Buddhism. Nanzan Library of Religion and Culture, no. 2. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1997. xxviii + 515 pp. $45.00 cloth, ISBN 0-8248-1908-X; $22.95 paper, ISBN 0-8248-1949-7. THE INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENT known as “Critical Buddhism” (hihan Bukkyõ −|[î) began around the mid-1980s in Sõtõ Zen circles, led by Hakamaya Noriaki and Matsumoto Shirõ, both Buddhologists as well as ordained Sõtõ priests. Since then it has indeed raised storm waves on the normally placid waters of Japanese academic Buddhist studies. “Criticism alone is Buddhism,” declares Hakamaya, by which he means the critical discrimination of truth from error. Aggressively normative, Critical Buddhism does not hesitate to pronounce on what represents “true” Buddhism and what does not. By its de³nition, Bud- dhism is simply the teachings of non-self (an„tman) and dependent origination (prat‡tya-samutp„da). Many of the most inµuential of Mah„y„na ideas, including notions of universal Buddha nature, tath„gata-garbha, original enlightenment, the nonduality of the Vimalak‡rti Sðtra, and the “absolute nothingness” of the Kyoto school, are all condemned as reverting to fundamentally non-Buddhist notions of „tman, that is, substantial essence or ground. Thus they are to be rejected as “not Buddhism”—the “pruning” of this volume’s title. -

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

Shields, James Mark

H-Buddhism Shields, James Mark Page published by A. Charles Muller on Tuesday, January 15, 2019 My Life in Buddhist Studies James Mark Shields Professor of Comparative Humanities and Asian Thought Inaugural Director, Bucknell Humanities Center Bucknell University First, I’d like to thank Chuck Prebish for the opportunity to contribute to this interesting and valuable project. Second, I am sure that my version of this story is considerably less engaging than those of my peers—especially those who came of age in the generation before mine; i.e., in the 1960s and 1970s. With that caveat (always good to lower expectations!), let’s begin. Family Connections It was in the early 1980s that, as a late adolescent, my curiosity was first piqued by Asian cultures and civilizations. The primary causal force was very close to home: my mother. For it was at this time, roughly the age of 12, that it began to dawn on me that my mother—a seemingly ordinary middle-aged and middle-class Canadian woman—was in fact the product of a somewhat more exotic, even tragic, upbringing. Born in Manila, the Philippines in 1937, of Scots, Spanish, and a tiny sliver of native Filipino heritage, she found herself at the tender age of 4 rounded up by an invading Japanese military force and placed in an internment camp on the grounds of Santo Tomas University in Manila, where she and her family were forced to reside for the next 3 years. Needless to say, these were difficult times, and though my mother’s memories are vague, she does recall a clear distinction between the ‘nice’ and ‘nasty’ Japanese guards, as well as the decreasing supplies of food as the war wore on and Japan went from aggressor to defender of the islands. -

Buddhist Spiritual Practices

Buddhist Spiritual Practices Thinking with Pierre Hadot on Buddhism, Philosophy, and the Path Edited by David V. Fiordalis Mangalam Press Berkeley, CA Mangalam Press 2018 Allston Way, Berkeley, CA USA www.mangalampress.org Copyright © 2018 by Mangalam Press. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be copied, reproduced, published, distributed, or stored electronically, photographically, or optically in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-89800-117-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018930282 Mangalam Press is an imprint of Dharma Publishing. The cover image depicts a contemporary example of Tibetan Buddhist instructional art: the nine stages on the path of “calming” (śamatha) meditation. Courtesy of Exotic India, www.exoticindia.com. Used with permission. ♾ Printed on acid-free paper. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Printed in the USA by Dharma Press, Cazadero, CA 95421 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 David V. Fiordalis Comparisons with Buddhism Some Remarks on Hadot, Foucault, and 21 Steven Collins Schools, Schools, Schools—Or, Must a Philosopher be Like a Fish? 71 Sara L. McClintock The Spiritual Exercises of the Middle Way: Madhyamakopadeśa with Hadot Reading Atiśa’s 105 James B. Apple Spiritual Exercises and the Buddhist Path: An Exercise in Thinking with and against Hadot 147 Pierre-Julien Harter the Philosophy of “Incompletion” The “Fecundity of Dialogue” and 181 Maria Heim Philosophy as a Way to Die: Meditation, Memory, and Rebirth in Greece and Tibet 217 Davey K. -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Tathagata-Garbha Sutra

Tathagata-garbha Sutra (Tripitaka No. 0666) Translated during the East-JIN Dynasty by Tripitaka Master Buddhabhadra from India Thus I heard one time: The Bhagavan was staying on Grdhra-kuta near Raja-grha in the lecture hall of a many-tiered pavilion built of fragrant sandalwood. He had attained buddhahood ten years previously and was accompanied by an assembly of hundred thousands of great bhikshus and a throng of bodhisattvas and great beings sixty times the number of sands in the Ganga. All had perfected their zeal and had formerly made offerings to hundred thousands of myriad legions of Buddhas. All could turn the Irreversible Dharma Wheel. If a being were to hear their names, he would become irreversible in the unsurpassed path. Their names were Bodhisattva Dharma-mati, Bodhisattva Simha-mati, Bodhisattva Vajra-mati, Bodhisattva Harmoniously Minded, bodhisattva Shri-mati, Bodhisattva Candra- prabha, Bodhisattva Ratna-prabha, Bodhisattva Purna-candra, Bodhisattva Vikrama, Bodhisattva Ananta-vikramin, Bodhisattva Trailokya-vikramin, Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva Maha-sthama-prapta, Bodhisattva Gandha-hastin, Bodhisattva Sugandha, Bodhisattva Surpassing Sublime Fragrance, Bodhisattva Supreme matrix, Bodhisattva Surya-garbha, Bodhisattva Ensign Adornment, Bodhisattva Great Arrayed Banner, Bodhisattva Vimala-ketu, Bodhisattva Boundless Light, Bodhisattva Light Giver, Bodhisattva Vimala-prabha, Bodhisattva Pramudita-raja, Bodhisattva Sada-pramudita, Bodhisattva Ratna-pani, Bodhisattva Akasha-garbha, Bodhisattva King of the Light -

18 Phases Or Realms

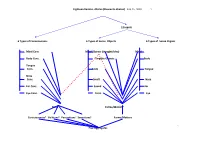

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Time and Eternity in Buddhism

TIME AND ETERNITY IN BUDDHISM by Shoson Miyamoto This essay consists of three main parts: linguistic, historical and (1) textual. I. To introduce the theory of time in Buddhism, let us refer to the Sanskrit and Pali words signifying "time". There are four of these: sa- maya, kala, ksana (khana) and adhvan (addhan). Samaya means a coming together, meeting, contract, agreement, opportunity, appointed time or proper time. Kala means time in general, being employed in the term kala- doctrine or kala-vada, which holds that time ripens or matures all things. In its special meaning kala signifies appointed or suitable time. It may also mean meal-time or the time of death, since both of these are most critical and serious times in our lives. Death is expressed as kala-vata in Pali, that is "one has passed his late hour." Ksana also means a moment, (1) The textual part is taken from the author's Doctoral Dissertation: Middle Way thought and Its Historical Development. which was submitted to the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1941 and published in 1944 (Kyoto: Hozokan). Material used here is from pp. 162-192. Originally this fromed the second part of "Philosophical Studies of the Middle," which was delivered at the Annual Meeting of the Philosophical Society, Imperial University of Tokyo, in 1939 and published in the Journal of Philosophical Studies (Nos. 631, 632, 633). Since at that time there was no other essay published on the time concept in Buddhism, these earlier studies represented a new and original contribution by the author. Up to now, in fact, such texts as "The Time of the Sage," "The Pith and Essence" have survived untouched.