Evidence from Changsha Xiang Chinese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

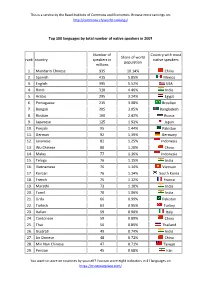

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

From Eurocentrism to Sinocentrism: the Case of Disposal Constructions in Sinitic Languages

From Eurocentrism to Sinocentrism: The case of disposal constructions in Sinitic languages Hilary Chappell 1. Introduction 1.1. The issue Although China has a long tradition in the compilation of rhyme dictionar- ies and lexica, it did not develop its own tradition for writing grammars until relatively late.1 In fact, the majority of early grammars on Chinese dialects, which begin to appear in the 17th century, were written by Europe- ans in collaboration with native speakers. For example, the Arte de la len- gua Chiõ Chiu [Grammar of the Chiõ Chiu language] (1620) appears to be one of the earliest grammars of any Sinitic language, representing a koine of urban Southern Min dialects, as spoken at that time (Chappell 2000).2 It was composed by Melchior de Mançano in Manila to assist the Domini- cans’ work of proselytizing to the community of Chinese Sangley traders from southern Fujian. Another major grammar, similarly written by a Do- minican scholar, Francisco Varo, is the Arte de le lengua mandarina [Grammar of the Mandarin language], completed in 1682 while he was living in Funing, and later posthumously published in 1703 in Canton.3 Spanish missionaries, particularly the Dominicans, played a signifi- cant role in Chinese linguistic history as the first to record the grammar and lexicon of vernaculars, create romanization systems and promote the use of the demotic or specially created dialect characters. This is discussed in more detail in van der Loon (1966, 1967). The model they used was the (at that time) famous Latin grammar of Elio Antonio de Nebrija (1444–1522), Introductiones Latinae (1481), and possibly the earliest grammar of a Ro- mance language, Grammatica de la Lengua Castellana (1492) by the same scholar, although according to Peyraube (2001), the reprinted version was not available prior to the 18th century. -

China Genetics

Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology? Paper for the Symposium : Human migrations in continental East Asia and Taiwan: genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence Geneva June 10-13, 2004. Université de Genève [DRAFT CIRCULATED FOR COMMENT] Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm Cambridge, Sunday, 06 June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES.......................................................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 The problem: linking linguistics, archaeology and genetics ................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodological issues............................................................................................................................. 3 2. The linguistic pattern of present-day China............................................................................................. 5 2.1 General .................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Sino-Tibetan........................................................................................................................................... -

The Survey on the Distribution of MC Fei and Xiao Initial Groups in Chinese Dialects

IALP 2020, Kuala Lumpur, Dec 4-6, 2020 The Survey on the Distribution of MC Fei and Xiao Initial Groups in Chinese Dialects Yan Li Xiaochuan Song School of Foreign Languages, School of Foreign Languages, Shaanxi Normal University, Shaanxi Normal University Xi’an, China /Henan Agricultural University e-mail: [email protected] Xi’an/Zhengzhou, China e-mail:[email protected] Abstract — MC Fei 非 and Xiao 晓 initial group discussed in this paper includes Fei 非, Fu groups are always mixed together in the southern 敷 and Feng 奉 initials, but does not include Wei part of China. It can be divided into four sections 微, while MC Xiao 晓 initial group includes according to the distribution: the northern area, the Xiao 晓 and Xia 匣 initials. The third and fourth southwestern area, the southern area, the class of Xiao 晓 initial group have almost southeastern area. The mixing is very simple in the palatalized as [ɕ] which doesn’t mix with Fei northern area, while in Sichuan it is the most initial group. This paper mainly discusses the first extensive and complex. The southern area only and the second class of Xiao and Xia initials. The includes Hunan and Guangxi where ethnic mixing of Fei and Xiao initials is a relatively minorities gather, and the mixing is very recent phonetic change, which has no direct complicated. Ancient languages are preserved in the inheritance with the phonological system of southeastern area where there are still bilabial Qieyun. The mixing mainly occurs in the southern sounds and initial consonant [h], but the mixing is part of the mainland of China. -

Xiang Dialects Xiāng Fāngyán 湘方言

◀ Xiang Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. Xiang Dialects Xiāng fāngyán 湘方言 Mandarin 普通话 (putonghua, literally “com- kingdom, which was established in the third century ce, moner’s language”) is the standard Chinese but it was greatly influenced by northern Chinese (Man- language. Apart from Mandarin, there are darin) at various times. The Chu kingdom occupied mod- other languages and dialects spoken in China. ern Hubei and Hunan provinces. Some records of the vocabulary used in the Chu kingdom areas can be found 湘 汉 Xiang is one of the ten main Chinese Han in Fangyan, compiled by Yang Xiong (53 bce– 18 ce), and dialects, and is spoken primarily throughout Shuowen jiezi, compiled by Xu Shen in 100 ce. Both works Hunan Province. give the impression that the dialect spoken in the Chu kingdom had some strong local features. The dialects spoken in Chu were influenced strongly he Xiang dialect group is one of the recognized by northern Chinese migrants. The first group of mi- ten dialect groups of spoken Chinese. Some 34 grants came into Hunan in 307– 312 ce. Most of them million people throughout Hunan Province came from Henan and Shanxi provinces and occupied speak one of the Xiang dialects. Speakers are also found Anxiang, Huarong, and Lixian in Hunan. In the mid- in Sichuan and Guangxi provinces. Tang dynasty, a large group of northern people came to The Xiang dialect group is further divided into New Hunan following the Yuan River into western Hunan. The Xiang (spoken in the north) and Old Xiang (spoken in the third wave of migrants arrived at the end of the Northern south). -

《中国学术期刊文摘》赠阅 《中国学术期刊文摘》赠阅 CHINESE SCIENCE ABSTRACTS (Monthly, Established in 2006) Vol.10 No.1, 2015 (Sum No.103) Published on January 15, 2015

《中国学术期刊文摘》赠阅 《中国学术期刊文摘》赠阅 CHINESE SCIENCE ABSTRACTS (Monthly, Established in 2006) Vol.10 No.1, 2015 (Sum No.103) Published on January 15, 2015 Chinese Science Abstracts Competent Authority: China Association for Science and Technology Contents Supporting Organization: Department of Society Affairs and Academic Activities China Association for Science and Technology Hot Topic Sponsor: Science and Technology Review Publishing House Ebola Virus………………………………………………………………………1 Publisher: Science and Technology Review Publishing House High Impact Papers Editor-in-chief: CHEN Zhangliang Highly Cited Papers TOP5……………………………………………………11 Chief of the Staff/Deputy Editor-in-chief: Acoustics (11) Agricultural Engineering (12) Agriculture Dairy Animal Science (14) SU Qing [email protected] Agriculture Multidisciplinary (16) Agronomy (18) Allergy (20) Deputy Chief of the Staff/Deputy Editor-in-chief: SHI Yongchao [email protected] Anatomy Morphology (22) Andrology (24) Anesthesiology (26) Deputy Editor-in-chief: SONG Jun Architecture (28) Astronomy Astrophysics (29) Automation Control Systems (31) Deputy Director of Editorial Department: Biochemical Research Methods (33) Biochemistry Molecular Biology (34) WANG Shuaishuai [email protected] WANG Xiaobin Biodiversity Conservation (35) Biology (37) Biophysics (39) Biotechnology Applied Microbiology (41) Cell Biology (42) Executive Editor of this issue: WANG Shuaishuai Cell Tissue Engineering (43) Chemistry Analytical (45) Director of Circulation Department: Chemistry Applied (47) Chemistry Inorganic -

Language Variation and Social Identity in Beijing

Language Variation and Social Identity in Beijing Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics Hui Zhao May 2017 School of Languages, Linguistics and Film Queen Mary University of London Declaration I, Hui Zhao, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my con- tribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party's copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Abstract This thesis investigates language variation among a group of young adults in Beijing, China, with an aim to advance our understanding of social meaning in a language and a society where the topic is understudied. In this thesis, I examine the use of Beijing Mandarin among Beijing- born university students in Beijing in relation to social factors including gender, social class, career plan, and future aspiration. -

Languages of Southeast Asia

Jiarong Horpa Zhaba Amdo Tibetan Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Wu Chinese Central Tibetan Khams Tibetan Muya Huizhou Chinese Eastern Xiangxi Miao Yidu LuobaLanguages of Southeast Asia Northern Tujia Bogaer Luoba Ersu Yidu Luoba Tibetan Mandarin Chinese Digaro-Mishmi Northern Pumi Yidu LuobaDarang Deng Namuyi Bogaer Luoba Geman Deng Shixing Hmong Njua Eastern Xiangxi Miao Tibetan Idu-Mishmi Idu-Mishmi Nuosu Tibetan Tshangla Hmong Njua Miju-Mishmi Drung Tawan Monba Wunai Bunu Adi Khamti Southern Pumi Large Flowery Miao Dzongkha Kurtokha Dzalakha Phake Wunai Bunu Ta w an g M o np a Gelao Wunai Bunu Gan Chinese Bumthangkha Lama Nung Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Norra Wusa Nasu Xiang Chinese Chug Nung Wunai Bunu Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Min Bei Chinese Nupbikha Lish Kachari Ta se N a ga Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nung Large Flowery Miao Nyenkha Chalikha Sartang Lisu Nung Lisu Southern Pumi Kalaktang Monpa Apatani Khamti Ta se N a ga Wusa Nasu Adap Tshangla Nocte Naga Ayi Nung Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Nocte Naga Lisu Large Flowery Miao Northern Dong Khamti Lipo Wusa NasuWhite Miao Nepali Nepali Lhao Vo Deori Luopohe Miao Ge Southern Pumi White Miao Nepali Konyak Naga Nusu Gelao GelaoNorthern Guiyang MiaoLuopohe Miao Bodo Kachari White Miao Khamti Lipo Lipo Northern Qiandong Miao White Miao Gelao Hmong Njua Eastern Qiandong Miao Phom Naga Khamti Zauzou Lipo Large Flowery Miao Ge Northern Rengma Naga Chang Naga Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Assamese Southern Guiyang Miao Southern Rengma Naga Khamti Ta i N u a Wusa Nasu Northern Huishui -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

The Diminutive Word Tsa42 in the Xianning Dialect: A

The Diminutive Word tsa42 in the Xianning Dialect: A Cognitive Approach* Xiaolong Lu University of Arizona [email protected] This study reports on the syntactic distribution and semantic features of a spoken word tsa42 as a form of diminutive address in the Xianning dialect. Two research questions are examined: what are the distributional patterns of the dialectal word tsa42 regarding its different functions in the Xianning dialect? And when this word serves as a suffix of nouns, why can it be widely used as a diminutive marker in the dialect? Based on interview data, I argue that (1) there are restrictions in using the diminutive word tsa42 together with adjectives and nouns, and certain countable nouns denoting huge and fierce animals, or large transportation tools, etc., cannot co-occur with the diminutive word tsa42; and (2) the markedness theory (Shi 2005) is used to explain that the diminutive suffix tsa42 can be used to highlight nouns denoting things of small sizes. The revised model of Radial Category (Jurafsky 1996) helps account for different categorizations metaphorically and metonymically extended from the prototype “child” in terms of tsa42, etc. This case study implies that a typological model for diminution needs to be built to connect the analysis of other diminutive words in Chinese dialects and beyond. 1. Introduction Showing loveliness or affection to small things is taken to be a kind of human nature, and the “diminutive function is among the grammatical primitives which seem to occur universally or near-universally in world languages” (Jurafsky 1996: 534). The term “diminutive” is expressed as a kind of word that has been modified to convey a slighter degree of its root * I want to give my thanks to Dr. -

Tungusic Languages

641 TUNGUSIC LANGUAGES he last Imperial family that reigned in Beij- Nanai or Goldi has about 7,000 speakers on the T ing, the Qing or Manchu dynasty, seized banks ofthe lower Amur. power in 1644 and were driven out in 1912. Orochen has about 2,000 speakers in northern Manchu was the ancestral language ofthe Qing Manchuria. court and was once a major language ofthe Several other Tungusic languages survive, north-eastern province ofManchuria, bridge- with only a few hundred speakers apiece. head ofthe Japanese invasion ofChina in the 1930s. It belongs to the little-known Tungusic group Numerals in Manchu, Evenki and Nanai oflanguages, usually believed to formpart ofthe Manchu Evenki Nanai ALTAIC family. All Tungusic languages are spo- 1 emu umuÅn emun ken by very small population groups in northern 2 juwe dyuÅr dyuer China and eastern Siberia. 3 ilan ilan ilan Manchu is the only Tungusic language with a 4 duin digin duin written history. In the 17th century the Manchu 5 sunja tungga toinga rulers ofChina, who had at firstruled through 6 ninggun nyungun nyungun the medium of MONGOLIAN, adapted Mongolian 7 nadan nadan nadan script to their own language, drawing some ideas 8 jakon dyapkun dyakpun from the Korean syllabary. However, in the 18th 9 uyun eÅgin khuyun and 19th centuries Chinese ± language ofan 10 juwan dyaÅn dyoan overwhelming majority ± gradually replaced Manchu in all official and literary contexts. From George L. Campbell, Compendium of the world's languages (London: Routledge, 1991) The Tungusic languages Even or Lamut has 7,000 speakers in Sakha, the Kamchatka peninsula and the eastern Siberian The mountain forest coast ofRussia. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang