Sinitic Grammar: Synchronic and Diachronic Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

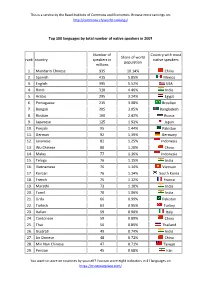

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

China Genetics

Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology? Paper for the Symposium : Human migrations in continental East Asia and Taiwan: genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence Geneva June 10-13, 2004. Université de Genève [DRAFT CIRCULATED FOR COMMENT] Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm Cambridge, Sunday, 06 June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES.......................................................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 The problem: linking linguistics, archaeology and genetics ................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodological issues............................................................................................................................. 3 2. The linguistic pattern of present-day China............................................................................................. 5 2.1 General .................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Sino-Tibetan........................................................................................................................................... -

《中国学术期刊文摘》赠阅 《中国学术期刊文摘》赠阅 CHINESE SCIENCE ABSTRACTS (Monthly, Established in 2006) Vol.10 No.1, 2015 (Sum No.103) Published on January 15, 2015

《中国学术期刊文摘》赠阅 《中国学术期刊文摘》赠阅 CHINESE SCIENCE ABSTRACTS (Monthly, Established in 2006) Vol.10 No.1, 2015 (Sum No.103) Published on January 15, 2015 Chinese Science Abstracts Competent Authority: China Association for Science and Technology Contents Supporting Organization: Department of Society Affairs and Academic Activities China Association for Science and Technology Hot Topic Sponsor: Science and Technology Review Publishing House Ebola Virus………………………………………………………………………1 Publisher: Science and Technology Review Publishing House High Impact Papers Editor-in-chief: CHEN Zhangliang Highly Cited Papers TOP5……………………………………………………11 Chief of the Staff/Deputy Editor-in-chief: Acoustics (11) Agricultural Engineering (12) Agriculture Dairy Animal Science (14) SU Qing [email protected] Agriculture Multidisciplinary (16) Agronomy (18) Allergy (20) Deputy Chief of the Staff/Deputy Editor-in-chief: SHI Yongchao [email protected] Anatomy Morphology (22) Andrology (24) Anesthesiology (26) Deputy Editor-in-chief: SONG Jun Architecture (28) Astronomy Astrophysics (29) Automation Control Systems (31) Deputy Director of Editorial Department: Biochemical Research Methods (33) Biochemistry Molecular Biology (34) WANG Shuaishuai [email protected] WANG Xiaobin Biodiversity Conservation (35) Biology (37) Biophysics (39) Biotechnology Applied Microbiology (41) Cell Biology (42) Executive Editor of this issue: WANG Shuaishuai Cell Tissue Engineering (43) Chemistry Analytical (45) Director of Circulation Department: Chemistry Applied (47) Chemistry Inorganic -

Languages of Southeast Asia

Jiarong Horpa Zhaba Amdo Tibetan Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Wu Chinese Central Tibetan Khams Tibetan Muya Huizhou Chinese Eastern Xiangxi Miao Yidu LuobaLanguages of Southeast Asia Northern Tujia Bogaer Luoba Ersu Yidu Luoba Tibetan Mandarin Chinese Digaro-Mishmi Northern Pumi Yidu LuobaDarang Deng Namuyi Bogaer Luoba Geman Deng Shixing Hmong Njua Eastern Xiangxi Miao Tibetan Idu-Mishmi Idu-Mishmi Nuosu Tibetan Tshangla Hmong Njua Miju-Mishmi Drung Tawan Monba Wunai Bunu Adi Khamti Southern Pumi Large Flowery Miao Dzongkha Kurtokha Dzalakha Phake Wunai Bunu Ta w an g M o np a Gelao Wunai Bunu Gan Chinese Bumthangkha Lama Nung Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Norra Wusa Nasu Xiang Chinese Chug Nung Wunai Bunu Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Min Bei Chinese Nupbikha Lish Kachari Ta se N a ga Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nung Large Flowery Miao Nyenkha Chalikha Sartang Lisu Nung Lisu Southern Pumi Kalaktang Monpa Apatani Khamti Ta se N a ga Wusa Nasu Adap Tshangla Nocte Naga Ayi Nung Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Nocte Naga Lisu Large Flowery Miao Northern Dong Khamti Lipo Wusa NasuWhite Miao Nepali Nepali Lhao Vo Deori Luopohe Miao Ge Southern Pumi White Miao Nepali Konyak Naga Nusu Gelao GelaoNorthern Guiyang MiaoLuopohe Miao Bodo Kachari White Miao Khamti Lipo Lipo Northern Qiandong Miao White Miao Gelao Hmong Njua Eastern Qiandong Miao Phom Naga Khamti Zauzou Lipo Large Flowery Miao Ge Northern Rengma Naga Chang Naga Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Assamese Southern Guiyang Miao Southern Rengma Naga Khamti Ta i N u a Wusa Nasu Northern Huishui -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

Tungusic Languages

641 TUNGUSIC LANGUAGES he last Imperial family that reigned in Beij- Nanai or Goldi has about 7,000 speakers on the T ing, the Qing or Manchu dynasty, seized banks ofthe lower Amur. power in 1644 and were driven out in 1912. Orochen has about 2,000 speakers in northern Manchu was the ancestral language ofthe Qing Manchuria. court and was once a major language ofthe Several other Tungusic languages survive, north-eastern province ofManchuria, bridge- with only a few hundred speakers apiece. head ofthe Japanese invasion ofChina in the 1930s. It belongs to the little-known Tungusic group Numerals in Manchu, Evenki and Nanai oflanguages, usually believed to formpart ofthe Manchu Evenki Nanai ALTAIC family. All Tungusic languages are spo- 1 emu umuÅn emun ken by very small population groups in northern 2 juwe dyuÅr dyuer China and eastern Siberia. 3 ilan ilan ilan Manchu is the only Tungusic language with a 4 duin digin duin written history. In the 17th century the Manchu 5 sunja tungga toinga rulers ofChina, who had at firstruled through 6 ninggun nyungun nyungun the medium of MONGOLIAN, adapted Mongolian 7 nadan nadan nadan script to their own language, drawing some ideas 8 jakon dyapkun dyakpun from the Korean syllabary. However, in the 18th 9 uyun eÅgin khuyun and 19th centuries Chinese ± language ofan 10 juwan dyaÅn dyoan overwhelming majority ± gradually replaced Manchu in all official and literary contexts. From George L. Campbell, Compendium of the world's languages (London: Routledge, 1991) The Tungusic languages Even or Lamut has 7,000 speakers in Sakha, the Kamchatka peninsula and the eastern Siberian The mountain forest coast ofRussia. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2019-065 (completed by Registration authority) Date: August 31, 2019 Primary Person submitting request: Kirk Miller Affiliation: E-mail address: kirkmiller at gmail dot com Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: Postal address for primary contact person for this request (in general, email correspondence will be used): PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests This form is to be used in requesting changes (whether creation, modification, or deletion) to elements of the ISO 639 Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages. The types of changes that are possible are to 1) modify the reference information for an existing code element, 2) propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group; 3) retire a code element from use, including merging its scope of denotation into that of another code element, 4) split an existing code element into two or more new language code elements, or 5) create a new code element for a previously unidentified language variety. Fill out section 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 below as appropriate, and the final section documenting the sources of your information. The process by which a change is received, reviewed and adopted is summarized on the final page of this form. -

Summary of Requested Changes Altogether 66 Requests Were Considered, Recommending 116 Explicit Changes in the Code Set

ISO 639-3 Change Requests Series 2019 Summary of Outcomes Melinda Lyons (SIL International), ISO 639-3 Registrar, 23 January 2020 Summary of requested changes Altogether 66 requests were considered, recommending 116 explicit changes in the code set. Of the 66 change requests, 16 have been rejected, 44 have been fully approved, 2 were partially approved, and two were withdrawn. Four requests are awaiting additional information for final consideration. Of the 106 explicit changes to individual codes which were decided, 45 were rejected and 61 accepted. The latter can be analyzed as follows: Deprecations (Retirements): o 12 deprecated as non-existent; o 1 deprecated as duplicate of another code; o 4 deprecated and merged into another language; o 3 split languages. New languages: o 11 newly created languages not previously associated with another language in the code set; o 14 languages created as a result of splits. Updates: o 11 name updates, either change to a name form or addition of a name form o 4 updates to denotation of a language code as a result of mergers o 1 update to membership of a macrolanguage. In addition to the numbered and posted change requests for 2019, there were a number of routine maintenance updates. 11 language types were changed from extinct to ancient and 15 were changed from extinct to historic. The history of any change request may be viewed on its documentation page which uses the pattern: https://iso639-3.sil.org/request/2019-004 Likewise, the history of any code element may be viewed on its documentation -

Language Distinctiveness*

RAI – data on language distinctiveness RAI data Language distinctiveness* Country profiles *This document provides data production information for the RAI-Rokkan dataset. Last edited on October 7, 2020 Compiled by Gary Marks with research assistance by Noah Dasanaike Citation: Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks (2016). Community, Scale and Regional Governance: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Vol. II. Oxford: OUP. Sarah Shair-Rosenfield, Arjan H. Schakel, Sara Niedzwiecki, Gary Marks, Liesbet Hooghe, Sandra Chapman-Osterkatz (2021). “Language difference and Regional Authority.” Regional and Federal Studies, Vol. 31. DOI: 10.1080/13597566.2020.1831476 Introduction ....................................................................................................................6 Albania ............................................................................................................................7 Argentina ...................................................................................................................... 10 Australia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Austria .......................................................................................................................... 14 Bahamas ....................................................................................................................... 16 Bangladesh .................................................................................................................. -

Operation China

Han Chinese, Xiang April 20 Location: Approximately 35 million held in Tiananmen speakers of Xiang Chinese — or Square, Beijing, to Hunanese — live in China.1 The demand political majority are located in Hunan reform was Province. Others inhabit 20 counties forcefully broken up of western Sichuan and parts of by the army on 4 northern Guangxi and northern June 1989. Fears Guangdong provinces. that China would revert to the Identity: The Xiang are traditionally excesses of the acknowledged as the most stubborn 1960s and 1970s and proud of all Chinese peoples. proved unfounded, “The people themselves… are the however, and China most clannish and conservative to be continued to open found in the whole empire, and have up and become a succeeded in keeping their province thriving part of the practically free from invasion by world community foreigners and even foreign ideas.”2 throughout the 1990s. Language: Xiang is a distinct Chinese language in transition. It is exposed to Customs: In 1911 Mandarin from several directions. the Xiang were Hunanese women once possessed described as “the their own writing system. It was taught best haters and Paul Hattaway by women to women and could not be best fighters in China. Long after the Christianity: In 1861 Welsh read by men.3 rest of the empire was open to missionary Griffith John met a Hunan missionary activity, Hunan kept its military mandarin, who “boasted of History: The People’s Republic of gates firmly closed against the the glory and martial courage of the China (1949– ): The Communists foreigner.”4 The Xiang are renowned Hunan men, and said there was no seized control of China in 1949. -

Evidence from Changsha Xiang Chinese

Journal of East Asian Linguistics (2019) 28:279–306 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-019-09196-2(0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) A structural account of the difference between achievements and accomplishments: evidence from Changsha Xiang Chinese Man Lu1 · Anikó Lipták2 · Rint Sybesma2,3 Received: 19 July 2018 / Accepted: 3 July 2019 / Published online: 27 August 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract This paper offers an analysis of ka41, an aspectual element in Changsha Xiang Chinese. It is argued that this element occupies a position in the inner- aspectual structure of the clause, between the higher aspectual marker ta21 and the lower elements expressing a lexical result (like clean in wash clean). On the basis of its co-occurrence with various verb types, we treat ka41 as an achievement marker: when present, it blocks any reading in which the denoted event proceeds along a multi-point scale, allowing only the instantaneous, two-point scale reading in which the beginning and the endpoint of the event coincide. On the basis of its syntactic distribution we argue that the syntactic position ka41 occupies is an intermediate aspectual projection (Asp2P) in the inner aspect domain, which is sandwiched between the lowest inner aspectual projection dedicated to telicity and the highest one signaling perfectivity (or realization of the end point). We review the impli- cations of the analysis for the aspectual domain of Mandarin clauses and point out that the intermediate inner aspectual projection (Asp2P) we introduce for Changsha appears to be a suitable syntactic position for the structural analysis of the small set of grammaticalized items generally known as “Phase complements” as well.