The Diminutive Word Tsa42 in the Xianning Dialect: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China

Entropy 2014, 16, 6313-6337; doi:10.3390/e16126313 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy Article Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China Xixi Chen 1, Tao Hu 1, Fu Ren 1,2,*, Deng Chen 1, Lan Li 1 and Nan Gao 1 1 School of Resource and Environment Science, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (X.C.); [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (N.G.) 2 Key Laboratory of Geographical Information System, Ministry of Education, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +86-27-87664557; Fax: +86-27-68778893. External Editor: Hwa-Lung Yu Received: 20 July 2014; in revised form: 31 October 2014 / Accepted: 26 November 2014 / Published: 1 December 2014 Abstract: Hubei Province is the hub of communications in central China, which directly determines its strategic position in the country’s development. Additionally, Hubei Province is well-known for its diverse landforms, including mountains, hills, mounds and plains. This area is called “The Province of Thousand Lakes” due to the abundance of water resources. Geographical names are exclusive names given to physical or anthropogenic geographic entities at specific spatial locations and are important signs by which humans understand natural and human activities. In this study, geographic information systems (GIS) technology is adopted to establish a geodatabase of geographical names with particular characteristics in Hubei Province and extract certain geomorphologic and environmental factors. -

Download Article

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 70 International Conference on Economy, Management and Entrepreneurship(ICOEME 2018) Research on the Path of Deep Fusion and Integration Development of Wuhan and Ezhou Lijiang Zhao Chengxiu Teng School of Public Administration School of Public Administration Zhongnan University of Economics and Law Zhongnan University of Economics and Law Wuhan, China 430073 Wuhan, China 430073 Abstract—The integration development of Wuhan and urban integration of Wuhan and Hubei, rely on and Ezhou is a strategic task in Hubei Province. It is of great undertake Wuhan. Ezhou City takes the initiative to revise significance to enhance the primacy of provincial capital, form the overall urban and rural plan. Ezhou’s transportation a new pattern of productivity allocation, drive the development infrastructure is connected to the traffic artery of Wuhan in of provincial economy and upgrade the competitiveness of an all-around and three-dimensional way. At present, there provincial-level administrative regions. This paper discusses are 3 interconnected expressways including Shanghai- the path of deep integration development of Wuhan and Ezhou Chengdu expressway, Wuhan-Ezhou expressway and from the aspects of history, geography, politics and economy, Wugang expressway. In terms of market access, Wuhan East and puts forward some suggestions on relevant management Lake Development Zone and Ezhou Gedian Development principles and policies. Zone try out market access cooperation, and enterprises Keywords—urban regional cooperation; integration registered in Ezhou can be named with “Wuhan”. development; path III. THE SPACE FOR IMPROVEMENT IN THE INTEGRATION I. INTRODUCTION DEVELOPMENT OF WUHAN AND EZHOU Exploring the path of leapfrog development in inland The degree of integration development of Wuhan and areas is a common issue for the vast areas (that is to say, 500 Ezhou is lower than that of central urban area of Wuhan, and kilometers from the coastline) of China’s hinterland. -

The Causes and Effects of the Development of Semi-Competitive

Central European University The Causes and Effects of the Development of Semi-Competitive Elections at the Township Level in China since the 1990s By Hairong Lai Thesis submitted in fulfillment for the degree of PhD, Department of Political Science, Central European University, Budapest, January 2008 Supervisor Zsolt Enyedi (Central European University) External Supervisor Maria Csanadi (Hungarian Academy of Sciences) CEU eTD Collection PhD Committee Tamas Meszerics (Central European University) Yongnian Zheng (Nottingham University) 1 Contents Summary..........................................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................6 Statements........................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................8 1.1 The literature on elections in China ....................................................................................8 1.2 Theories on democratization .............................................................................................15 1.3 Problems in the existing literature on semi-competitive elections in China .....................21 1.4 Agenda of the current research..........................................................................................26 -

A Simple Model to Assess Wuhan Lock-Down Effect and Region Efforts

A simple model to assess Wuhan lock-down effect and region efforts during COVID-19 epidemic in China Mainland Zheming Yuan#, Yi Xiao#, Zhijun Dai, Jianjun Huang & Yuan Chen* Hunan Engineering & Technology Research Centre for Agricultural Big Data Analysis & Decision-making, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, Hunan, 410128, China. #These authors contributed equally to this work. * Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y.C. (email: [email protected]) (Submitted: 29 February 2020 – Published online: 2 March 2020) DISCLAIMER This paper was submitted to the Bulletin of the World Health Organization and was posted to the COVID-19 open site, according to the protocol for public health emergencies for international concern as described in Vasee Moorthy et al. (http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.251561). The information herein is available for unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited as indicated by the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Intergovernmental Organizations licence (CC BY IGO 3.0). RECOMMENDED CITATION Yuan Z, Xiao Y, Dai Z, Huang J & Chen Y. A simple model to assess Wuhan lock-down effect and region efforts during COVID-19 epidemic in China Mainland [Preprint]. Bull World Health Organ. E-pub: 02 March 2020. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.254045 Abstract: Since COVID-19 emerged in early December, 2019 in Wuhan and swept across China Mainland, a series of large-scale public health interventions, especially Wuhan lock-down combined with nationwide traffic restrictions and Stay At Home Movement, have been taken by the government to control the epidemic. -

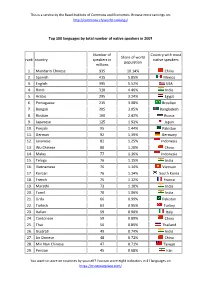

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Exploring Your Surname Exploring Your Surname

Exploring Your Surname As of 6/09/10 © 2010 S.C. Meates and the Guild of One-Name Studies. All rights reserved. This storyboard is provided to make it easy to prepare and give this presentation. This document has a joint copyright. Please note that the script portion is copyright solely by S.C. Meates. The script can be used in giving Guild presentations, although permission for further use, such as in articles, is not granted, to conform with prior licenses executed. The slide column contains a miniature of the PowerPoint slide for easy reference. Slides Script Welcome to our presentation, Exploring Your Surname. Exploring Your Surname My name is Katherine Borges, and this presentation is sponsored by the Guild of One- Name Studies, headquartered in London, England. Presented by Katherine Borges I would appreciate if all questions can be held to the question and answer period at Sponsored by the Guild of One-Name Studies the end of the presentation London, England © 2010 Guild of One-Name Studies. All rights reserved. www.one-name.org Surnames Your surname is an important part of your identity. How did they come about This presentation will cover information about surnames, including how they came Learning about surnames can assist your about, and what your surname can tell you. In addition, I will cover some of the tools genealogy research and techniques available for you to make discoveries about your surname. Historical development Regardless of the ancestral country for your surname, learning about surnames can assist you with your genealogy research. Emergence of variants Frequency and distribution The presentation will cover the historical development of surnames, the emergence of variants, what the current frequency and distribution of your surname can tell you DNA testing to make discoveries about the origins, and the use of DNA testing to make discoveries about your surname. -

Excess Mortality in Wuhan City and Other Parts of China During BMJ: First Published As 10.1136/Bmj.N415 on 24 February 2021

RESEARCH Excess mortality in Wuhan city and other parts of China during BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.n415 on 24 February 2021. Downloaded from the three months of the covid-19 outbreak: findings from nationwide mortality registries Jiangmei Liu,1 Lan Zhang,2 Yaqiong Yan,3 Yuchang Zhou,1 Peng Yin,1 Jinlei Qi,1 Lijun Wang,1 Jingju Pan,2 Jinling You,1 Jing Yang,1 Zhenping Zhao,1 Wei Wang,1 Yunning Liu,1 Lin Lin,1 Jing Wu,1 Xinhua Li,4 Zhengming Chen,5 Maigeng Zhou1 1The National Center for Chronic ABSTRACT 8.32, 5.19 to 17.02), mainly covid-19 related, but and Non-communicable Disease OBJECTIVE a more modest increase in deaths from certain Control and Prevention, Chinese To assess excess all cause and cause specific other diseases, including cardiovascular disease Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), Xicheng mortality during the three months (1 January to (n=2347; 408 v 316 per 100 000; 1.29, 1.05 to 1.65) District, 100050, Beijing, China 31 March 2020) of the coronavirus disease 2019 and diabetes (n=262; 46 v 25 per 100 000; 1.83, 2Hubei Provincial Center for (covid-19) outbreak in Wuhan city and other parts of 1.08 to 4.37). In Wuhan city (n=13 districts), 5954 Disease Control and Prevention, China. additional (4573 pneumonia) deaths occurred in Wuhan, Hubei, China 2020 compared with 2019, with excess risks greater 3Wuhan Center for Disease DESIGN Control and Prevention, Wuhan, Nationwide mortality registries. in central than in suburban districts (50% v 15%). -

People's Republic of China: Hubei Enshi Qing River Upstream

Project Administration Manual Project Number: 47048-002 March 2020 People’s Republic of China: Hubei Enshi Qing River Upstream Environment Rehabilitation Contents ABBREVIATIONS iv I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 II. IMPLEMENTATION PLANS 8 A. Project Readiness Activities 8 B. Overall Project Implementation Plan 9 III. PROJECT MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENTS 12 A. Project Implementation Organizations – Roles and Responsibilities 12 B. Key Persons Involved in Implementation 15 C. Project Organization Structure 16 IV. COSTS AND FINANCING 17 A. Detailed Cost Estimates by Expenditure Category 19 B. Allocation and Withdrawal of Loan Proceeds 20 C. Detailed Cost Estimates by Financier 21 D. Detailed Cost Estimates by Outputs 22 E. Detailed Cost Estimates by Year 23 F. Contract and Disbursement S-curve 24 G. Fund Flow Diagram 25 V. FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT 26 A. Financial Management Assessment 26 B. Disbursement 26 C. Accounting 28 D. Auditing and Public Disclosure 28 VI. PROCUREMENT AND CONSULTING SERVICES 30 A. Advance Contracting and Retroactive Financing 30 B. Procurement of Goods, Works and Consulting Services 30 C. Procurement Plan 31 D. Consultant's Terms of Reference 40 VII. SAFEGUARDS 43 A. Environment 43 B. Resettlement 45 C. Ethnic Minorities 52 VIII. GENDER AND SOCIAL DIMENSIONS 53 A. Summary Poverty Reduction and Social Strategy 53 B. Gender Development and Gender Action Plan 53 C. Social Action Plan 54 IX. PERFORMANCE MONITORING, EVALUATION, REPORTING AND COMMUNICATION 61 A. Project Design and Monitoring Framework 61 B. Monitoring 68 C. Evaluation -

From Eurocentrism to Sinocentrism: the Case of Disposal Constructions in Sinitic Languages

From Eurocentrism to Sinocentrism: The case of disposal constructions in Sinitic languages Hilary Chappell 1. Introduction 1.1. The issue Although China has a long tradition in the compilation of rhyme dictionar- ies and lexica, it did not develop its own tradition for writing grammars until relatively late.1 In fact, the majority of early grammars on Chinese dialects, which begin to appear in the 17th century, were written by Europe- ans in collaboration with native speakers. For example, the Arte de la len- gua Chiõ Chiu [Grammar of the Chiõ Chiu language] (1620) appears to be one of the earliest grammars of any Sinitic language, representing a koine of urban Southern Min dialects, as spoken at that time (Chappell 2000).2 It was composed by Melchior de Mançano in Manila to assist the Domini- cans’ work of proselytizing to the community of Chinese Sangley traders from southern Fujian. Another major grammar, similarly written by a Do- minican scholar, Francisco Varo, is the Arte de le lengua mandarina [Grammar of the Mandarin language], completed in 1682 while he was living in Funing, and later posthumously published in 1703 in Canton.3 Spanish missionaries, particularly the Dominicans, played a signifi- cant role in Chinese linguistic history as the first to record the grammar and lexicon of vernaculars, create romanization systems and promote the use of the demotic or specially created dialect characters. This is discussed in more detail in van der Loon (1966, 1967). The model they used was the (at that time) famous Latin grammar of Elio Antonio de Nebrija (1444–1522), Introductiones Latinae (1481), and possibly the earliest grammar of a Ro- mance language, Grammatica de la Lengua Castellana (1492) by the same scholar, although according to Peyraube (2001), the reprinted version was not available prior to the 18th century. -

The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany

Kathrin Dräger, Mirjam Schmuck, Germany 319 The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany Abstract The German Surname Atlas (Deutscher Familiennamenatlas, DFA) project is presented below. The surname maps are based on German fixed network telephone lines (in 2005) with German postal districts as graticules. In our project, we use this data to explore the areal variation in lexical (e.g., Schröder/Schneider µtailor¶) as well as phonological (e.g., Hauser/Häuser/Heuser) and morphological (e.g., patronyms such as Petersen/Peters/Peter) aspects of German surnames. German surnames emerged quite early on and preserve linguistic material which is up to 900 years old. This enables us to draw conclusions from today¶s areal distribution, e.g., on medieval dialect variation, writing traditions and cultural life. Containing not only German surnames but also foreign names, our huge database opens up possibilities for new areas of research, such as surnames and migration. Due to the close contact with Slavonic languages (original Slavonic population in the east, former eastern territories, migration), original Slavonic surnames make up the largest part of the foreign names (e.g., ±ski 16,386 types/293,474 tokens). Various adaptations from Slavonic to German and vice versa occurred. These included graphical (e.g., Dobschinski < Dobrzynski) as well as morphological adaptations (hybrid forms: e.g., Fuhrmanski) and folk-etymological reinterpretations (e.g., Rehsack < Czech Reåak). *** 1. The German surname system In the German speech area, people generally started to use an addition to their given names from the eleventh to the sixteenth century, some even later. -

The Survey on the Distribution of MC Fei and Xiao Initial Groups in Chinese Dialects

IALP 2020, Kuala Lumpur, Dec 4-6, 2020 The Survey on the Distribution of MC Fei and Xiao Initial Groups in Chinese Dialects Yan Li Xiaochuan Song School of Foreign Languages, School of Foreign Languages, Shaanxi Normal University, Shaanxi Normal University Xi’an, China /Henan Agricultural University e-mail: [email protected] Xi’an/Zhengzhou, China e-mail:[email protected] Abstract — MC Fei 非 and Xiao 晓 initial group discussed in this paper includes Fei 非, Fu groups are always mixed together in the southern 敷 and Feng 奉 initials, but does not include Wei part of China. It can be divided into four sections 微, while MC Xiao 晓 initial group includes according to the distribution: the northern area, the Xiao 晓 and Xia 匣 initials. The third and fourth southwestern area, the southern area, the class of Xiao 晓 initial group have almost southeastern area. The mixing is very simple in the palatalized as [ɕ] which doesn’t mix with Fei northern area, while in Sichuan it is the most initial group. This paper mainly discusses the first extensive and complex. The southern area only and the second class of Xiao and Xia initials. The includes Hunan and Guangxi where ethnic mixing of Fei and Xiao initials is a relatively minorities gather, and the mixing is very recent phonetic change, which has no direct complicated. Ancient languages are preserved in the inheritance with the phonological system of southeastern area where there are still bilabial Qieyun. The mixing mainly occurs in the southern sounds and initial consonant [h], but the mixing is part of the mainland of China. -

Xiang Dialects Xiāng Fāngyán 湘方言

◀ Xiang Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. Xiang Dialects Xiāng fāngyán 湘方言 Mandarin 普通话 (putonghua, literally “com- kingdom, which was established in the third century ce, moner’s language”) is the standard Chinese but it was greatly influenced by northern Chinese (Man- language. Apart from Mandarin, there are darin) at various times. The Chu kingdom occupied mod- other languages and dialects spoken in China. ern Hubei and Hunan provinces. Some records of the vocabulary used in the Chu kingdom areas can be found 湘 汉 Xiang is one of the ten main Chinese Han in Fangyan, compiled by Yang Xiong (53 bce– 18 ce), and dialects, and is spoken primarily throughout Shuowen jiezi, compiled by Xu Shen in 100 ce. Both works Hunan Province. give the impression that the dialect spoken in the Chu kingdom had some strong local features. The dialects spoken in Chu were influenced strongly he Xiang dialect group is one of the recognized by northern Chinese migrants. The first group of mi- ten dialect groups of spoken Chinese. Some 34 grants came into Hunan in 307– 312 ce. Most of them million people throughout Hunan Province came from Henan and Shanxi provinces and occupied speak one of the Xiang dialects. Speakers are also found Anxiang, Huarong, and Lixian in Hunan. In the mid- in Sichuan and Guangxi provinces. Tang dynasty, a large group of northern people came to The Xiang dialect group is further divided into New Hunan following the Yuan River into western Hunan. The Xiang (spoken in the north) and Old Xiang (spoken in the third wave of migrants arrived at the end of the Northern south).