The Neolithic Ofsouthern China-Origin, Development, and Dispersal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatiotemporal Changes and the Driving Forces of Sloping Farmland Areas in the Sichuan Region

sustainability Article Spatiotemporal Changes and the Driving Forces of Sloping Farmland Areas in the Sichuan Region Meijia Xiao 1 , Qingwen Zhang 1,*, Liqin Qu 2, Hafiz Athar Hussain 1 , Yuequn Dong 1 and Li Zheng 1 1 Agricultural Clean Watershed Research Group, Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences/Key Laboratory of Agro-Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] (M.X.); [email protected] (H.A.H.); [email protected] (Y.D.); [email protected] (L.Z.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Simulation and Regulation of Water Cycle in River Basin, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing 100048, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-82106031 Received: 12 December 2018; Accepted: 31 January 2019; Published: 11 February 2019 Abstract: Sloping farmland is an essential type of the farmland resource in China. In the Sichuan province, livelihood security and social development are particularly sensitive to changes in the sloping farmland, due to the region’s large portion of hilly territory and its over-dense population. In this study, we focused on spatiotemporal change of the sloping farmland and its driving forces in the Sichuan province. Sloping farmland areas were extracted from geographic data from digital elevation model (DEM) and land use maps, and the driving forces of the spatiotemporal change were analyzed using a principal component analysis (PCA). The results indicated that, from 2000 to 2015, sloping farmland decreased by 3263 km2 in the Sichuan province. The area of gently sloping farmland (<10◦) decreased dramatically by 1467 km2, especially in the capital city, Chengdu, and its surrounding areas. -

Crop Systems on a County-Scale

Supporting information Chinese cropping systems are a net source of greenhouse gases despite soil carbon sequestration Bing Gaoa,b, c, Tao Huangc,d, Xiaotang Juc*, Baojing Gue,f, Wei Huanga,b, Lilai Xua,b, Robert M. Reesg, David S. Powlsonh, Pete Smithi, Shenghui Cuia,b* a Key Lab of Urban Environment and Health, Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiamen 361021, China b Xiamen Key Lab of Urban Metabolism, Xiamen 361021, China c College of Resources and Environmental Sciences, Key Laboratory of Plant-soil Interactions of MOE, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China d College of Geography Science, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing 210046, China e Department of Land Management, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310058, PR China f School of Agriculture and Food, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, 3010 Australia g SRUC, West Mains Rd. Edinburgh, EH9 3JG, Scotland, UK h Department of Sustainable Agriculture Sciences, Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, AL5 2JQ. UK i Institute of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UU, UK Bing Gao & Tao Huang contributed equally to this work. Corresponding author: Xiaotang Ju and Shenghui Cui College of Resources and Environmental Sciences, Key Laboratory of Plant-soil Interactions of MOE, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China. Phone: +86-10-62732006; Fax: +86-10-62731016. E-mail: [email protected] Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1799 Jimei Road, Xiamen 361021, China. Phone: +86-592-6190777; Fax: +86-592-6190977. E-mail: [email protected] S1. The proportions of the different cropping systems to national crop yields and sowing area Maize was mainly distributed in the “Corn Belt” from Northeastern to Southwestern China (Liu et al., 2016a). -

Tianjin Travel Guide

Tianjin Travel Guide Travel in Tianjin Tianjin (tiān jīn 天津), referred to as "Jin (jīn 津)" for short, is one of the four municipalities directly under the Central Government of China. It is 130 kilometers southeast of Beijing (běi jīng 北京), serving as Beijing's gateway to the Bohai Sea (bó hǎi 渤海). It covers an area of 11,300 square kilometers and there are 13 districts and five counties under its jurisdiction. The total population is 9.52 million. People from urban Tianjin speak Tianjin dialect, which comes under the mandarin subdivision of spoken Chinese. Not only is Tianjin an international harbor and economic center in the north of China, but it is also well-known for its profound historical and cultural heritage. History People started to settle in Tianjin in the Song Dynasty (sòng dài 宋代). By the 15th century it had become a garrison town enclosed by walls. It became a city centered on trade with docks and land transportation and important coastal defenses during the Ming (míng dài 明代) and Qing (qīng dài 清代) dynasties. After the end of the Second Opium War in 1860, Tianjin became a trading port and nine countries, one after the other, established concessions in the city. Historical changes in past 600 years have made Tianjin an unique city with a mixture of ancient and modem in both Chinese and Western styles. After China implemented its reforms and open policies, Tianjin became one of the first coastal cities to open to the outside world. Since then it has developed rapidly and become a bright pearl by the Bohai Sea. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

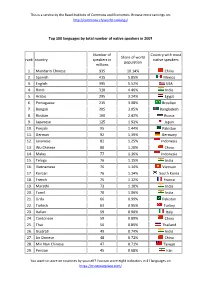

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Ceramic's Influence on Chinese Bronze Development

Ceramic’s Influence on Chinese Bronze Development Behzad Bavarian and Lisa Reiner Dept. of MSEM College of Engineering and Computer Science September 2007 Photos on cover page Jue from late Shang period decorated with Painted clay gang with bird, fish and axe whorl and thunder patterns and taotie design from the Neolithic Yangshao creatures, H: 20.3 cm [34]. culture, H: 47 cm [14]. Flat-based jue from early Shang culture Pou vessel from late Shang period decorated decorated with taotie beasts. This vessel with taotie creatures and thunder patterns, H: is characteristic of the Erligang period, 24.5 cm [34]. H: 14 cm [34]. ii Table of Contents Abstract Approximate timeline 1 Introduction 2 Map of Chinese Provinces 3 Neolithic culture 4 Bronze Development 10 Clay Mold Production at Houma Foundry 15 Coins 16 Mining and Smelting at Tonglushan 18 China’s First Emperor 19 Conclusion 21 References 22 iii The transition from the Neolithic pottery making to the emergence of metalworking around 2000 BC held significant importance for the Chinese metal workers. Chinese techniques sharply contrasted with the Middle Eastern and European bronze development that relied on annealing, cold working and hammering. The bronze alloys were difficult to shape by hammering due to the alloy combination of the natural ores found in China. Furthermore, China had an abundance of clay and loess materials and the Chinese had spent the Neolithic period working with and mastering clay, to the point that it has been said that bronze casting was made possible only because the bronze makers had access to superior ceramic technology. -

Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia Were Not the Descendants of Yan Huang

E-Leader Brno 2019 Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia were not the Descendants of Yan Huang Soleilmavis Liu, Activist Peacepink, Yantai, Shandong, China Many Chinese people claimed that they are descendants of Yan Huang, while claiming that they are descendants of Hua Xia. (Yan refers to Yan Di, Huang refers to Huang Di and Xia refers to the Xia Dynasty). Are these true or false? We will find out from Shanhaijing ’s records and modern archaeological discoveries. Abstract Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas ) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Yan Di, Huang Di, Zhuan Xu, Di Jun and Shao Hao. These were not only the names of groups, but also the names of individuals, who were regarded by many groups as common male ancestors. These groups first lived in the Pamirs Plateau, soon gathered in the north of the Tibetan Plateau and west of the Qinghai Lake and learned from each other advanced sciences and technologies, later spread out to other places of China and built their unique ancient cultures during the Neolithic Age. The Yan Di’s offspring spread out to the west of the Taklamakan Desert;The Huang Di’s offspring spread out to the north of the Chishui River, Tianshan Mountains and further northern and northeastern areas;The Di Jun’s and Shao Hao’s offspring spread out to the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, where the Di Jun’s offspring lived in the west of the Shao Hao’s territories, which were near the sea or in the Shandong Peninsula.Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed the authenticity of Shanhaijing ’s records. -

2 Days Leshan Giant Buddha and Mount Emei Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 2 days Leshan Giant Buddha and Mount Emei tour https://windhorsetour.com/emei-leshan-tour/leshan-emei-2-day-tour Chengdu Mount Emei Leshan Chengdu A classic trip to Leshan and Mount Emei only takes 2 days. Leshan Grand Buddha is the biggest sitting Buddha in the world and Mount Emei is one of the four Buddhist Mountains in China. Type Private Duration 2 days Theme Culture and Heritage Trip code WS-302 From £ 214 per person £ 195 you save £ 19 (10%) Itinerary Mt.Emei lies in the southern area of Sichuan basin. It is one of the four sacred Buddhist Mountains in China. It is towering, beautiful, old and mysterious and is like a huge green screen standing in the southwest of the Chengdu Plain. Its main peak, the Golden Summit, is 3099 meters above the sea level, seemingly reaching the sky. Standing on the top of it, you can enjoy the snowy mountains in the west and the vast plain in the east. In addition in Golden Summit there are four spectacles: clouds sea, sunrise, Buddha rays and saint lamps. Leshan Grand Buddha is the biggest sitting Buddha in the world. It was begun to built in 713AD in Tang Dynasty, took more than 90 years to finish this huge statue. And it sits at Lingyue Mountain, at the Giant Buddha Cliff, you will find out a lot of stunning small buddha caves, you will be astonished by this human project. Leshan Grand Buddha and Mt.Emei both were enlisted in the world natural and cultural heritage by the UNESCO in 1996. -

MEDIEVAL WORLD from the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade W@

The History of the M E D I E V A L WORLD % Also by Susan Wise Bauer The History of the Ancient World: From the Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome (W. W. Norton, 2007) The Well-Educated Mind: A Guide to the Classical Education You Never Had (W. W. Norton, 2003) The Story of the World: History for the Classical Child (Peace Hill Press) Volume I: Ancient Times (rev. ed., 2006) Volume II: The Middle Ages (rev. ed. 2007) Volume III: Early Modern Times (2004) Volume IV: The Modern Age (2005) The Complete Writer:Writing with Ease (Peace Hill Press, 2008) The Art of the Public Grovel: Sexual Sina and Public Confession in America (Princeton University Press, 2008) With Jessie Wise The Well-Trained Mind: A Guide to Classical Education at Home (rev. ed., W. W. Norton, 2009) The History of the MEDIEVAL WORLD From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade W@ S u s a n W i s e B a u e r B W . W . Norton New York London Copyright © 2010 by Susan Wise Bauer All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110. Maps designed by Susan Wise Bauer and Sarah Park and created by Sarah Park Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, pages 000–000 constitute an extension of the copyright page. Manufacturing by Book Design by Margaret M. -

Settlement Patterns, Chiefdom Variability, and the Development of Early States in North China

JOURNAL OF ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 15, 237±288 (1996) ARTICLE NO. 0010 Settlement Patterns, Chiefdom Variability, and the Development of Early States in North China LI LIU School of Archaeology, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia Received June 12, 1995; revision received May 17, 1996; accepted May 26, 1996 In the third millennium B.C., the Longshan culture in the Central Plains of northern China was the crucial matrix in which the ®rst states evolved from the basis of earlier Neolithic societies. By adopting the theoretical concept of the chiefdom and by employing the methods of settlement archaeology, especially regional settlement hierarchy and rank-size analysis, this paper introduces a new approach to research on the Longshan culture and to inquiring about the development of the early states in China. Three models of regional settlement pattern correlating to different types of chiefdom systems are identi®ed. These are: (1) the centripetal regional system in circumscribed regions representing the most complex chiefdom organizations, (2) the centrifugal regional system in semi-circumscribed regions indicating less integrated chiefdom organization, and (3) the decentral- ized regional system in noncircumscribed regions implying competing and the least complex chief- dom organizations. Both external and internal factors, including geographical condition, climatic ¯uctuation, Yellow River's changing course, population movement, and intergroup con¯ict, played important roles in the development of complex societies in the Longshan culture. As in many cultures in other parts of the world, the early states in China emerged from a system of competing chiefdoms, which was characterized by intensive intergroup con¯ict and frequent shifting of political centers. -

A 5,600-Year-Old Wooden Well in Zhejiang Province, China

A 5,600-year-old wooden well in Zhejiang Province, China Jiu J. Jiao Abstract In 1973, traces of China’s early Neolithic plus ancien puits en bois retrouvé en Chine à l’heure Hemudu culture (7,000–5,000 BP) were discovered in the actuelle. Le site du puits comporte plus de 200 éléments village of Hemudu in Yuyao County, Zhejiang Province, en bois, et peut être divisé en deux parties interne et in the lower Yangtze River coastal plain. The site has externe. La partie externe est composée de 28 pieux yielded animal and plant remains in large quantities and ceinturant un étang. La partie interne, constituant le puits large numbers of logs secured with tenon and mortise en lui-même, est située au milieu de l’étang. Les parois du joints, commonly used in wooden buildings and other puits sont recouvertes de pieux en bois jointifs, renforcés wooden structures. For hydrogeologists, the most inter- par une croisée en bois. Les 28 pieux de la partie externe esting structure is an ancient wooden well. The well is du site composaient peut-être partiellement un abri pour le believed to be about 5,600 years old, which makes it the puits, suggérant ainsi que la culture Hemudu prenait déjà oldest wooden well yet found in China. The well site en considération l’hygiène et la protection de l’alimenta- contains over 200 wooden components and can be divided tion en eau. into inner and outer parts. The outer part consists of 28 piles around a pond. The inner part, the wooden well Resumen En 1973 se descubrieron trazas de la Cultura itself, lies in the middle of the pond. -

A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments

2011 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (iCBBE 2011) Wuhan, China 10 - 12 May 2011 Pages 1 - 867 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1129C-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-5088-6 1/7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ALGORITHMS, MODELS, SOFTWARE AND TOOLS IN BIOINFORMATICS: A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments ............................................................1 Hongbin Lee, Bo Wang, Xiaoming Wu, Yonggang Liu, Wei Gao, Huili Li, Xu Wang, Feng He A New Promoter Recognition Method Based On Features Optimal Selection.................................................................5 Lan Tao, Huakui Chen, Yanmeng Xu, Zexuan Zhu A Center Closeness Algorithm For The Analyses Of Gene Expression Data ...................................................................9 Huakun Wang, Lixin Feng, Zhou Ying, Zhang Xu, Zhenzhen Wang A Novel Method For Lysine Acetylation Sites Prediction ................................................................................................ 11 Yongchun Gao, Wei Chen Weighted Maximum Margin Criterion Method: Application To Proteomic Peptide Profile ....................................... 15 Xiao Li Yang, Qiong He, Si Ya Yang, Li Liu Ectopic Expression Of Tim-3 Induces Tumor-Specific Antitumor Immunity................................................................ 19 Osama A. O. Elhag, Xiaojing Hu, Weiying Zhang, Li Xiong, Yongze Yuan, Lingfeng Deng, Deli Liu, Yingle Liu, Hui Geng Small-World Network Properties Of Protein Complexes: Node Centrality And Community Structure