North Korea,” Predicting the Effect of Russia's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media and Civil Society in the Russian Protests, December 2011

Department of Informatics and Media Social Science – major in Media and Communication Studies Fall 2013 Master Two Years Thesis Social Media and Civil Society in the Russian Protests, December 2011 The role of social media in engagement of people in the protests and their self- identification with civil society Daria Dmitrieva Fall 2013 Supervisor: Dr. Gregory Simons Researcher at Uppsala Centre for Russian and Eurasian Studies 1 2 ABSTRACT The study examines the phenomenon of the December protests in Russia when thousands of citizens were involved in the protest movement after the frauds during the Parliamentary elections. There was a popular opinion in the Internet media that at that moment Russia experienced establishment of civil society, since so many people were ready to express their discontent publically for the first time in 20 years. The focus of this study is made on the analysis of the roles that social media played in the protest movement. As it could be observed at the first glance, recruiting and mobilising individuals to participation in the rallies were mainly conducted via social media. The research analyses the concept of civil society and its relevance to the protest rhetoric and investigates, whether there was a phenomenon of civil society indeed and how it was connected to individuals‘ motivation for joining the protest. The concept of civil society is discussed through the social capital, social and political trust, e- democracy and mediatisation frameworks. The study provides a comprehensive description of the events, based on mainstream and new media sources, in order to depict the nature and the development of the movement. -

Opposition in Authoritarian Regimes – a Case Study of Russian Non-Systemic Opposition1

DOI 10.14746/ssp.2017.4.12 Olga Na d s k a k u ł a -ka c z m a r c z y k Uniwersytet Papieski Jana Pawła II w Krakowie Opposition in authoritarian regimes – a case study of Russian non-systemic opposition1 Abstract: According to Juan Linz, authoritarian rulers permit limited, powerless po- litical pluralism and organization of elections, but they make it very clear that a change in power is impossible and the opposition cannot take over. Elections in authoritarian regimes are a part of nominally democratic institutions and help rulers to legitimize the regime. They are not free or fair, and therefore do not present any opportunity for the opposition to win and change the political system afterward. The question could be asked, what kind of action the opposition should undertake in order to improve its strength. That is the main problem nowadays for non-systemic opposition in the Russian Federation. On the one hand, the opposition has a problem gaining access to elections, but on the other hand, it knows that even if it could take part, the elections would not be democratic. This article tries to shed light on the strategies of the non-systemic Russian opposi- tion and the possibility of its impact on Russian society when the government tries to marginalize, weaken and eventually destroy the non-systemic opposition. The paper provides a critical analysis of the literature and documents on the topic. Key words: non-systemic opposition, authoritarianism, Kremlin, protest movement ith reference to its title, the text aims to examine non-systemic Wopposition in Russia. -

A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects the Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society

The Russian Opposition: A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects The Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society By Julia Pettengill Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 1 First published in 2012 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society 8th Floor – Parker Tower, 43-49 Parker Street, London, WC2B 5PS Tel: 020 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2012 All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its directors Designed by Genium, www.geniumcreative.com ISBN 978-1-909035-01-0 2 About The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society: A cross-partisan, British think-tank. Our founders and supporters are united by a common interest in fostering a strong British, European and American commitment towards freedom, liberty, constitutional democracy, human rights, governmental and institutional reform and a robust foreign, security and defence policy and transatlantic alliance. The Henry Jackson Society is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales under company number 07465741 and a charity registered in England and Wales under registered charity number 1140489. For more information about Henry Jackson Society activities, our research programme and public events please see www.henryjacksonsociety.org. 3 CONTENTS Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 5 About the Author 6 About the Russia Studies Centre 6 Acknowledgements 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 INTRODUCTION 11 CHAPTER -

Download Directly from the Website

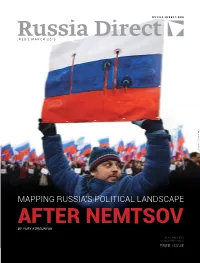

RUSSIA-DIRECT.ORG |#20 | MARCH 2015 © ILIA PITALEV / RIA NOVOSTI © ILIA PITALEV BY YURY KORGUNYUK AVAILABLE FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY FREE ISSUE Mapping Russia’s political landscape afteR neMtsov | #20 | MaRcH 2015 EDITor’s noTE The murder of opposition politician Boris Nemtsov fundamentally changed the landscape of Russian politics. In the month that has passed since his murder, both Western and Russian commentators have weighed in on what this means – not just for the fledgling Russian opposition movement, but also for the Kremlin. What follows is a comprehensive overview of the landscape of political Ekaterina forces in Russia today and their reaction to Nemtsov’s murder. Zabrovskaya The author of this Brief is Yury Korgunyuk, an experienced political ana- Editor-in-Chief lyst in Moscow and the head of the political science department at the Moscow-based Information Science for Democracy (INDEM) Foundation. Also, we would like to inform you, our loyal readers, that later this spring, Russia Direct will introduce a paid subscription model and will begin charging for its reports. There will be more information regarding this ini- tiative on our website www.russia-direct.org and weekly newsletters. We are thrilled about this development and hope that you will support us as the RD editorial team continues to produce balanced analytical sto- ries on topics untold in the American media. Keeping the dialogue be- tween the United States and Russia going is a challenging but important task today. Please feel free to email me directly at [email protected] -

Russia: Background and U.S. Policy

Russia: Background and U.S. Policy Cory Welt Analyst in European Affairs August 21, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44775 Russia: Background and U.S. Policy Summary Over the last five years, Congress and the executive branch have closely monitored and responded to new developments in Russian policy. These developments include the following: increasingly authoritarian governance since Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidential post in 2012; Russia’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region and support of separatists in eastern Ukraine; violations of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty; Moscow’s intervention in Syria in support of Bashar al Asad’s government; increased military activity in Europe; and cyber-related influence operations that, according to the U.S. intelligence community, have targeted the 2016 U.S. presidential election and countries in Europe. In response, the United States has imposed economic and diplomatic sanctions related to Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Syria, malicious cyber activity, and human rights violations. The United States also has led NATO in developing a new military posture in Central and Eastern Europe designed to reassure allies and deter aggression. U.S. policymakers over the years have identified areas in which U.S. and Russian interests are or could be compatible. The United States and Russia have cooperated successfully on issues such as nuclear arms control and nonproliferation, support for military operations in Afghanistan, the Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs, the International Space Station, and the removal of chemical weapons from Syria. In addition, the United States and Russia have identified other areas of cooperation, such as countering terrorism, illicit narcotics, and piracy. -

Detailed Information About Vitaly Shklyarov from Wikipedia Russia

Detailed Information about Vitaly Shklyarov from Wikipedia Russia Vitaly Valentinovich Shklyarov (born July 11, 1976, Gomel, BSSR, USSR) is a Belarusian political consultant and political strategist. Vitaly Shklyarov started his career as a political consultant in Germany. He graduated From the University of Fechta [en] with a degree in Social and political science in 2002. During his studies, Vitaly worked For the campaign of Angela Merkel[1]. In 2008, he moved to the United States where he became a volunteer at the presidential campaign headquarters of Barack Obama. Despite his experience in Germany, Vitaly started his career in the United States as a Field agitator[2]. At the beginning of his work at the Obama headquarters, Vitaly made calls from the basement located in the call center of the headquarters of the Democratic national Committee. [3] In 2012, Shklyarov became the head of the field Department for the Tammy Baldwin campaign. He was responsible for creating field infrastructure and a network of agitators in the state of Wisconsin. [3] The campaign was won, and Tammy Baldwin became the First ever Female Senator From Wisconsin, as well as the First openly gay Senator. In 2012, Shklyarov was also responsible for the mobilization part of Barack Obama's campaign in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. [4] The campaign to mobilize voters beFore polling day (GOTV) in the city oF Milwaukee won two awards from the American Association of politicalconsultants(AAPC). In 2014, he worked on Ro Hanna's campaign For the US Congress. He was responsible For the Internet campaign and was chieF oF staFF in Cupertino, CaliFornia. -

Sofya Glazunova Thesis

DIGITAL MEDIA AS A TOOL FOR NON- SYSTEMIC OPPOSITION IN RUSSIA: A CASE STUDY OF ALEXEY NAVALNY’S POPULIST COMMUNICATIONS ON YOUTUBE Sofya Glazunova Bachelor, Master Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Communication Creative Industry Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2020 Keywords Content analysis; digital activism; investigative journalism; Alexey Navalny; network society; political communication; political performance; populism; press freedom; Vladimir Putin; Russian opposition; Russian politics; Russian media; truth; visual aesthetics; YouTube. Digital Media as a Tool for Non-Systemic Opposition in Russia: A Case Study of Alexey Navalny’s Populist Communications on YouTube i Abstract This Doctor of Philosophy project explores how Russia’s opposition figurehead Alexey Navalny uses YouTube’s affordances to communicate populist discourses that establish him as a successful leader and combatant of the elite of long-running leader Vladimir Putin. The project draws on theories of populism, investigative journalism, and digital media. Text transcripts and screenshots of Navalny’s YouTube videos during his electoral campaign for the 2018 presidential election are studied through mixed-method content analysis. Political communication in the 21st century is characterised in many countries by a decline in trust in conventional news media, the emergence of new political communication actors such as social media platforms and the rise of populist content. The constant search for new journalistic practices that take advantage of the affordances of new and alternative media has led many political activists to create new communication projects that seek to challenge and expose political elites by playing a watchdog role in society. -

Download (PDF)

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Comments Dress Rehearsal for Russia’s Presidential Election WP S Moscow Tightens Grip on Regional Governors and Budgets Fabian Burkhardt and Janis Kluge Fifteen Russian regions and annexed Sevastopol elected new governors on 10 September 2017. The process reveals the Kremlin’s response to rising socio-economic tensions in Russia’s regions: changing their leaders. A string of older regional bosses rooted within their local elites have been forced to make way for a younger generation of political managers over whom Moscow holds greater sway. The regions’ financial independence has been curtailed again too. For the Kremlin, this round of voting represented the final test before the presidential election scheduled for 18 March 2018 – and it passed off largely successfully. But the next presidential term will also see growing uncertain- ty over Vladimir Putin’s successor in the Kremlin. These latest centralisation moves are designed to counter potential political risks ahead of time. But they weaken the incen- tives for governors to invest in the long-term development of their regions. The regional and local elections held on respectable showing with 262 of 1,502 seats 10 September 2017 in eighty of the eighty- (17.4 percent). In these 125 Moscow districts three federal subjects (plus annexed Crimea however, United Russia also increased its and Sevastopol) included sixteen guberna- share to 77 percent of the seats. torial contests. The results confirm a trend The Presidential Administration under already seen in the 2016 Duma elections: First Deputy Chief of Staff Sergey Kiriyenko the already ascendant United Russia was treated the sixteen direct gubernatorial able to expand its hold on power, while the races as the principal dress rehearsal for Kremlin-loyal “systemic” opposition parties the 2018 presidential election. -

Repression and Autocracy As Russia Heads Into State Duma Elections Sabine Fischer

NO. 40 JUNE 2021 Introduction Repression and Autocracy as Russia Heads into State Duma Elections Sabine Fischer Russia is experiencing a wave of state repression ahead of parliamentary elections on 19 September 2021. The crackdown is unusually harsh and broad, extending into pre- viously unaffected areas and increasingly penetrating the private sphere of Russian citizens. For years the Russian state had largely relied on the so-called “power verti- cal” and on controlling the information space through propaganda and marginalisa- tion of independent media. The political leadership, so it would appear, no longer regards such measures as sufficient to secure its power and is increasingly resorting to repression. The upshot is a further hardening of autocracy. Even German NGOs are experiencing growing pressure from the Russian state. This trend cannot be expected to slow, still less reverse in the foreseeable future. Repression – wherever it occurs – involves of repression – restrictions and violence – restrictions (of civil rights and liberties) and have increased noticeably in recent months. physical violence. Russia has seen a string The state continues to rely primarily on the of political assassinations and assassination former but has also expanded its use of the attempts over the past decades. The poison- latter. ing of Alexei Navalny is only the most recent case, following on the spectacular murder of Boris Nemtsov in February 2015 What Is New? and numerous other attacks at home and abroad. In Russia’s Chechen Republic, Three aspects are new. The measures are, Ramzan Kadyrov has entrenched violence firstly, much larger-scale. During the against opponents and civil society as the nationwide demonstrations in late January foundation of his power. -

Russia Without Putin 242

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Sakwa, Richard (2020) The Putin Paradox. I. B. Tauris Bloomsbury, United Kingdom, 338 pp. ISBN 978-1-78831-830-3. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/80013/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html i THE PUTIN PARADOX 99781788318303_pi-306.indd781788318303_pi-306.indd i 115-Oct-195-Oct-19 112:25:332:25:33 ii 99781788318303_pi-306.indd781788318303_pi-306.indd iiii 115-Oct-195-Oct-19 112:25:332:25:33 iii THE PUTIN PARADOX Richard Sakwa 99781788318303_pi-306.indd781788318303_pi-306.indd iiiiii 115-Oct-195-Oct-19 112:25:332:25:33 iv I.B. TAURIS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, I.B. -

National and Urban Politics Converge in Moscow: Will Local Activism Prevail? Anna Zhelnina

National and Urban Politics Converge in Moscow: Will Local Activism Prevail? Anna Zhelnina Recent elections in Moscow and across Russia reflect the convergence of local activism and national anti-Kremlin politics. Late on the night of September 8, 2019, when Muscovites checked the results for that day’s Moscow City Council election, they realized that their vote actually meant something for the first time in many years. The candidates backed by United Russia, the ruling party, had lost in 20 districts out of 45. United Russia kept the majority, but compared to the 38 seats they controlled in the previous city council, this result looked like a loss. The Moscow City Council election was in the spotlight that day, but elections also took place at various levels across Russia: several governors, city councils, regional parliaments, and municipal deputies. This election differed from the previous electoral campaigns in Putin’s Russia because of “smart voting”: an idea and technology developed by the Anti-Corruption Foundation, a nonprofit headed by Aleksey Navalny, one of the most active and notable opposition politicians in Russia. “Smart voting” had one goal: to topple as many United Russia candidates as possible, at all levels of elections. Instead of picking an ideologically “correct” candidate, it suggested a single candidate in each district for opposition voters to support based on the candidate’s likelihood to win, calculated by an algorithm based on previous election and polling data. The system worked best in Moscow. United Russia suffered some losses across Russia, but it retained most of its seats (Englund 2019). -

Lashmankin and Others Group of Cases V Russian Federation

SECRETARIAT / SECRÉTARIAT SECRETARIAT OF THE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS SECRÉTARIAT DU COMITÉ DES MINISTRES Contact: Zoe Bryanston-Cross Tel: 03.90.21.59.62 Date: 29/04/2020 DH-DD(2020)377 Document distributed under the sole responsibility of its author, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers. Meeting: 1377th meeting (June 2020) (DH) Communication from an NGO (20/04/2020) in the Lashmankin and Others group of cases v. Russian Federation (Application No. 57818/09) Information made available under Rule 9.2 of the Rules of the Committee of Ministers for the supervision of the execution of judgments and of the terms of friendly settlements. * * * * * * * * * * * Document distribué sous la seule responsabilité de son auteur, sans préjuger de la position juridique ou politique du Comité des Ministres. Réunion : 1377e réunion (juin 2020) (DH) Communication d’une ONG (20/04/2020) relative au groupe d’affaires Lashmankin et autres c. Fédération de Russie (requête n° 57818/09) [anglais uniquement] Informations mises à disposition en vertu de la Règle 9.2 des Règles du Comité des Ministres pour la surveillance de l’exécution des arrêts et des termes des règlements amiables. DH-DD(2020)377: Rule 9.2 Communication from an NGO in Lashmankin v. Russian Federation. Document distributed under the sole responsibility of its author, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers. e EMORIAL DGI 20 AVR. 2020 SERVICE DE L’EXECUTION DES ARRETS DE LA CEDH Submission by the NGOs Human Rights Center Memorial and OVD-Info under Rule 9.2 of the Rules of the Committee of Ministers for the Supervision of the Execution of Judgments and of the Terms of Friendly Settlements on implementation of the general measures in the case of Lashmankin et al.