Interactional Straining and the Neoliberal Self: Learning English In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mizuho China Business Express Economic Journal (No

July 19, 2016 Mizuho Bank (China), Ltd. Corporate Banking Coordination Division ―The macroeconomy― Mizuho China Business Express Economic Journal (No. 58) Summary China’s real GDP (gross domestic product) grew by 6.7% y-o-y in April–June, the same level as January–March. June’s economic indicators were mixed, with some up slightly and some down slightly on May. If moves to eliminate overcapacity and other structural reforms accelerate from the 2H onwards, this will place more downward pressure on the economy. The question is whether China will be able to promote structural reform while maintaining jobs and growth. 1. June’s economic indicators deteriorated slightly on the whole ・ Growth hit +6.7% in April–June too ・ Investment fell slightly ・ Retail sales of consumer goods accelerated slightly ・ Property prices continued to grow at a slower pace in first-tier cities ・ Exports and imports both fell ・ The CPI growth rate slowed, mainly due to stable vegetable prices ・ There was a net increase in new loans, with total social financing also increasing 2. Movement on the employment and earnings environment and to eliminate overcapacity ・ ‘China faces challenges in maintaining household income growth’ (National Bureau of Statistics) ・ ‘Strict penalties will be applied for failure to reach targets for eliminating overcapacity’ (National Development and Reform Commission) - 1 - 1. June’s economic indicators deteriorated slightly on the whole ・Growth hit +6.7% in April–June too On July 15, the National Bureau of Statistics announced that China’s real GDP (gross domestic product) had grown by 6.7% on the same period last year (all figures from here on refer to ‘same-period previous-year’ growth unless otherwise specified) in both January–June and April–June1. -

Cronología China 2020

Cronología China 2020 Enero 01.01. Entra en vigor la Ley de Inversión Extranjera. El Banco Central anuncia un recorte de 50 puntos básicos en el coeficiente de reserva obligatoria para las instituciones financieras. Nueva regulación para mejorar el entorno empresarial. Discurso de Año Nuevo de la presidenta taiwanesa, Tsai Ing-wen. 02.01. Xi Jinping firma una orden de movilización nacional para el entrenamiento de las fuerzas armadas. Hu Chunhua insiste en más esfuerzos para ganar la batalla contra la pobreza. Grave accidente de un helicóptero militar en Taiwán en el que fallece el Jefe del Estado Mayor para la Defensa, Shen Yi-ming, y otras siete personas más. 03.01. Xi Jinping preside la sexta reunión del Comité Central del PCCh para asuntos económicos y financieros. Wang Huning centra la publicidad en el logro de la sociedad modestamente acomodada. Informan de manifestaciones y detenciones en Hong Kong. China planea hasta 50 misiones de lanzamiento espacial en 2020. Beijing pide moderación en las tensiones entre EEUU e Irán. 04.01. El presidente de Kiribbati, Taneti Mamau, inicia una visita de Estado a China. Luo Huining, nuevo director de la Oficina de Enlace en Hong Kong. Se intensifican los rumores sobre el estallido de una nueva epidemia de SARS en Wuhan. Altos funcionarios de Shaanxi son expulsados del PCCh. Wang Yi conversa telefónicamente con su homologo ruso Lavrov sobre la crisis en Oriente Medio. Taiwán a la cabeza en Asia en términos de igualdad de género. 1 Grupos laborales se manifiestan en Taipéi para exigir a los partidos atención a las políticas en esta materia. -

China's Trade Unions and Workers in the Current Reform Process

tS. tr. îk "Wadittg the River by Feeling for Rocks" China's Trade Unions and Workers in the Current Reform Process Hong Wung B. S. L. (Beijing UniversitY) Centre for Labour Studies Universig of Adelaide Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts Table of Contents Abstract 1 Statement iii Acknowledgements iv List of Tables V Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Reforms in the Labour System and Changes in Industrial Relations 20 1.1 Changes in the System of Ownership 21 1..2 Changes in the System of Employment Allocation 22 1.3 Changes in the System of Income Distributions 26 1..4 Changes in the Labour Security System 32 1.5 Changes in the Housing System J/ 1.6 Significant changes in industrial relations brought õ- about by reforms in the various economic systems 3/ Chapter 2 Detrimental Effects of the Reform on Workers 48 2.I A great number of production-suspensions (totai suspensions, partial suspensions) have occurred among state owned enterprises, enterprises making losses and workers losing jobs 48 2.2 Non-payment or delayed payment of workers' wages 49 2.3 Rapid rise of inflation 51 2.4 Medical costs have become heavy burdens for the workers 51 2.5 Workers' housing difficulties 52 2.6 Unfair wealth distribution and the polarisation of the rich and the poor 53 2.7 An impoverished urban working class is taking shape 57 2.8. Current conditions of the Chinese workers in the foreign-capital-invested and private enterprises 67 2.9 The total number and the severity of industrial accidents in China has reached an unprecedented -

Latest Developments on Foreign Investment in the Medical Care

Contents Business Tianjin / November 2012 06 BIZ BRIEFS 12 NUMBERS ECONOMY 14 November China Economy Report DIALOGUE 16 Fintan O’Doherty, General Manager, Tangla Hotel Tianjin 20 John Williams, Managing Director, International SOS’ China SUMMER DAVOS 24 Crisis Zone Tianjin: Where is the Water? FEATURE STORY 28 Hollywood Comes to China INVESTMENT ▲ Specialist in Luxury Service: Tangla Tianjin’s Top Man 30 Indonesia: Asia’s Ideal Investment Opportunity As part of the prestigious Luxury Collection hotel ensemble, the Tangla Hotel Tianjin is taking the Chinese hospitality industry to new highs. Through its elite service and stunning LEGAL ASSISTANCE blend of oriental and international ambience, the Tangla brand is differentiating itself from 36 China VAT reform pilot plan in Tianjin the countless big name international hotel chains on the market. See P16 POLICY EXPLANATION 40 Latest Developments on Foreign Investment ◄ Indonesia: Asia’s Ideal in the Medical Care Industry in China Investment Opportunity TECH “Invest in remarkable Indonesia”. That is 44 Iphone 5: Buy or Sell the advice of the island-nation’s Investment Coordinating Board in its latest adverts IPR aimed at enticing foreign investors. 48 Utility Model Patents in China Perfectly nestled between Asia and Australia’s booming consumer markets, HR Indonesia presents one of the best money 50 HR Localisation is Much More Than Hiring making opportunities of our era. According Natives to the IMF’s estimates, the country’s GDP will grow by an impressive 6.1% this year. 53 NEW APPOINTMENTS -

Made in China Journal: Vol. 1, Issue 3, 2016

MADE IN CHINA 2016 A Quarterly on Chinese Labour, Civil Society, and Rights ISSUE 3, 2016 WHAT WORKING CHINESE WORKERS FOCUS ON CHINESE PARADISE UNDER CLASS IN CHINA? AND THE LEGAL LABOUR AND CONSTRUCTION William Hurst SYSTEM INVESTMENT IN Christian Sorace Aaron Halegua AFRICA MADE IN 2016 CHINAA Quarterly on Chinese Labour, Civil Society, and Rights Made in China Made in China is a quarterly on Chinese labour, civil society, and rights. This project has been produced with the financial assistance of the Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW), Australian National University, and the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 654852. The views expressed are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the European Union, CIW, or the institutions to which the authors are affiliated. 2016 ISSUE #3 JULY-SEPTEMBER 2016 ISSN 2206-9119 EDITORS TABLE OF CONTENTS Ivan Franceschini Kevin Lin EDITORIAL (P.5) Nicholas Loubere COPY-EDITING HEART OF DARKNESS? A CHINESE EMPIRE IN Sharon Strange Ivan Franceschini THE MAKING? (P.30) Kevin Lin Jixia Lu PRODUCTION AND DESIGN Nicholas Loubere Tommaso Facchin A WINDOW ON ASIA (P.34) ISSUE CONTRIBUTORS BRIEFS (P.6) Tom Barnes BHARAT BANDH: MILLIONS Mukete Beyongo Dynamic CHALLENGE MODI’S Gordon Crawford CHINA COLUMNS (P.9) LABOUR AGENDA (P.35) Aaron Halegua Tom Barnes William Hurst THE CHINESE WORKING Jixia Lu CLASS (P.11) Elisa Nesossi William Hurst Christian Sorace WORK OF ARTS (P.39) CHINESE WORKERS AND PHOTO -

Prog Printing

China Employment Forum Beijing, 28-30 April 2004 Programme ____________________________________________________________ Tuesday, 27 April 2004 8:00-20:00 Delegates arrive and register at lounge of Building A, Beijing Hotel Day 1 – Wednesday, 28 April 2004 Plenary session 8:30 Delegates take buses at the gate of Building A of Beijing Hotel to the Great Hall of the People 8:40-8:50 Entrance to the Great Hall of the People 09:10-10:00 Opening plenary cere mony (Small auditorium, the Great Hall of the People ) Chair: Mr. Wang Dongjin, Vice Minister, MOLSS Participation: All participants Opening remark: Mr. Huang Ju, Vice Prime Minister, China Keynote speeches: - Mr. Somavia, Diretor-General, ILO - M r. Zheng Silin, Minister, MOLSS 10:00-10:30 Tea/Coffee Break 10:30-12:00 1st Plenary session: Globalization, Restructuring and Employment Promotion (Part I) (Small auditorium, the Great Hall of the People ) Chair: Mr. Hultin, Executive Director, ILO Participants: All participants - Remarks by the Chair - Mr. Zhu Zhixin, Vice Minister of State Development and Reform Commission, China - Ms. Ma. Nieves R. Confesor, Dean of Institute of Management and former Secretary of Labour, Philippines - Mr. Xu Zhenhuan, Vice President of ACFTU, China - Mr. Ng Eng Hen, Minister for Manpower and Minister of State for Education, Singapore - Mr. Chen Lantong, Vice President of CEC, China - Mr. Xiao Jie, Vice Minister of Finance, China - Mr. Murat Basesgioglu, Minister of Labour and Social Security, Turkey - Mr. Shao Ning, Vice Minister of State Asset Management Committee, China - Ms. Wu Xiaoling, Deputy President of People’s Bank of China - Mr. Zhang Xiaojian, Vice Minister of MOLSS, China 12:00-14:00 Adjourned, return to Beijing Hotel Lunch 1 14:00-16:00 2nd Plenary session: Panel Discussion on International Experience (Banquet Hall, 1st floor of Building C, Beijing Hotel) Chair: Dr. -

Made-In-China-03-2016.Pdf

MADE IN CHINA 2016 A Quarterly on Chinese Labour, Civil Society, and Rights ISSUE 3, 2016 WHAT WORKING CHINESE WORKERS FOCUS ON CHINESE PARADISE UNDER CLASS IN CHINA? AND THE LEGAL LABOUR AND CONSTRUCTION William Hurst SYSTEM INVESTMENT IN Christian Sorace Aaron Halegua AFRICA MADE IN 2016 CHINAA Quarterly on Chinese Labour, Civil Society, and Rights Made in China Made in China is a quarterly on Chinese labour, civil society, and rights. This project has been produced with the financial assistance of the Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW), Australian National University, and the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 654852. The views expressed are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the European Union, CIW, or the institutions to which the authors are affiliated. 2016 ISSUE #3 JULY-SEPTEMBER 2016 ISSN 2206-9119 EDITORS TABLE OF CONTENTS Ivan Franceschini Kevin Lin EDITORIAL (P.5) Nicholas Loubere COPY-EDITING HEART OF DARKNESS? A CHINESE EMPIRE IN Sharon Strange Ivan Franceschini THE MAKING? (P.30) Kevin Lin Jixia Lu PRODUCTION AND DESIGN Nicholas Loubere Tommaso Facchin A WINDOW ON ASIA (P.34) ISSUE CONTRIBUTORS BRIEFS (P.6) Tom Barnes BHARAT BANDH: MILLIONS Mukete Beyongo Dynamic CHALLENGE MODI’S Gordon Crawford CHINA COLUMNS (P.9) LABOUR AGENDA (P.35) Aaron Halegua Tom Barnes William Hurst THE CHINESE WORKING Jixia Lu CLASS (P.11) Elisa Nesossi William Hurst Christian Sorace WORK OF ARTS (P.39) CHINESE WORKERS AND PHOTO -

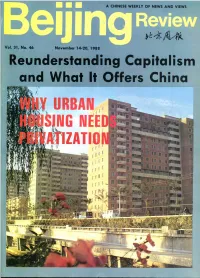

Reunderstanding Capitalism and What It Offers China Capturing a Unique Scene

CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS I' Vol. 31, No. 46 November 14-20, 1988 Reunderstanding Capitalism and What It Offers China Capturing a unique scene. Wang Wenlan HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK BeijingR«?it^ Reunderstandlng Capitalism VOU 3i, NO. 46 NOV. 14-20 • In a frank and. systematic appraisal of modern capitalism. CONTENTS Xu Jiatun, head of the Xinhua News Agency's Hong Kong NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 branch, calls for the rejection of stereotyped views of capitalist societies. He acknowledges that great changes have taken place Public Tip-Offs Aid Drive in their social and economic practices, and that they still possess Against Corruption a large potential for developing their productive forces. Xu also EVENTSARENDS 5-9 claims that capitalism's positive features and achievements should be assimilated into the task of building socialism with Revving Up Rural Reform . Chinese characteristics (p. 18). Foreign Contracts Will Be Respected UN Awards Disability Worker Thrcc-Gorgcs Plan: Public Tip-offs Aid Anti-Corruptlon Drive I-inalization Needed Pugwash Ponders Regional • This year. 900 corruption reporting centres have opened Peace across China to collect and process information supplied by the Wccklv Chronicle public about official malfeasance. The centres have both played (Oct. 31-Nov. 6) a major role in the recovery of millions of yiian's worth of goods INTERNATIONAL 10-13 and money and helped to promote clean government. The Supreme People's Procuratorate is now drawing up a series of r\ Nations Rally: regulations to standardize corruption reporting work across Middle East: Tripartite the country (p. 4). Talks Promote Peace FRG-USSR: Kohl Visit Warms Relations Israel: Major Parties Vic for Privatization of Urban Housing Swing Votes The Privatization of Urban • Until now, housing provision in China's cities has alwasy Housing 14 been regarded as a welfare service. -

El 19° Congreso Nacional Del Partido Comunista De China

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Facultad de Economía Centro de Estudios China-México Número 1, 2018 El 19° Congreso Nacional del Partido Comunista de China Eugenio Anguiano Roch Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Dr. Enrique Graue Wiechers Rector Dr. Leonardo Lomelí Vanegas Secretario General Mtra. Mónica González Contró Abogada General Dr. Alberto K. Oyama Nakagawa Secretario de Desarrollo Institucional Mtro. Javier de la Fuente Hernández Secretario de Atención a la Comunidad Universitaria Ing. Leopoldo Silva Gutiérrez Secretario Administrativo Facultad de Economía Mtro. Eduardo Vega López Director Lic. Rosa Carmina Ramírez Contreras Secretario General Lic. Porfirio Díaz Rodríguez Secretario Administrativo Lic. Dulce María Ruedas Moreno Coordinadora de Comunicación Social Lic. Ricardo Iglesias Flores Coordinador de Publicaciones Centro de Estudios China-México Dr. Enrique Dussel Peters Coordinador Dra. Yolanda Trápaga Delfín Responsable Editor Responsable: Dr. Sergio Efrén Martínez Rivera Comité Editorial: Alejandro Álvarez Bejar, Eugenio Anguiano Roch, Romer Cornejo Bustamante, Huiqiang Cheng, Leonel Corona Treviño, Marcos Cordeiro Pires, Enrique Dussel Peters, Octavio Fernández, Juan José Ling, Xue Dong Liu, Ignacio Martínez Cortés, Jorge Eduardo Navarrete López, Manuel Pérez García, María Teresa Rodríguez y Rodríguez, Xiaoping Song, Hongbo Sun, Mauricio Trápaga Delfín, Yolanda Trápaga Delfín, Zhimin Yang, Yongheng Wu (†). Diseño de portada: Mauricio Trápaga Delfín Corrección de estilo: Stella Cuéllar Cuadernos de Trabajo del Cechimex, revista bimestral, 2018. Editor Responsable: Sergio Efrén Martínez Rivera. Número de certificado de reserva otorgado por el Instituto Nacional del Derecho de Autor para versión impresa: 04-2010-071617584500-102. Número de certificado de licitud de título y de contenido (15252). Domicilio de la Publicación: Centro de Estudios China-México de la Facultad de Economía, edificio “B”, segundo piso, Ciudad Universitaria. -

Chapter 1 U.S.-China Economic and Trade Relations

CHAPTER 1 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND TRADE RELATIONS SECTION 1: YEAR IN REVIEW: ECONOMICS AND TRADE Introduction China is navigating a complex economic transformation as it expe- riences a slower pace of growth. The Chinese leadership proclaimed during the 2013 Third Plenary Session of the 18th Chinese Com- munist Party (CCP) Central Committee (hereafter, “Third Plenum”) that it is working toward a more market-based economic system. However, Party documents and offi cial actions indicate the Chinese government’s approach to reform is different from the liberal mar- ket reform Western observers expect. By “reform,” China’s leaders mean an economy that more effi ciently achieves the strategic goals of the state. While reform in the Chinese sense allows for incremen- tal movements toward a free market in certain areas, it precludes any changes that substantially reduce the government’s power over the economy. Beijing’s state-directed approach raises questions about the sus- tainability of China’s economic growth. Government stimulus has largely accrued to the state sector while the private sector struggles to secure credit, endangering China’s rebalancing. Within China’s economic downturn, a tale of two Chinas is emerging. In one, tradi- tional drivers of growth—heavy industry and low-end manufactur- ing—are in decline, while in another, newer sectors—services, con- sumer goods, and technology—are burgeoning. Still, the old economy remains critical for some provinces, and the new economy—so vital to China’s future growth—is nascent, underfunded, -

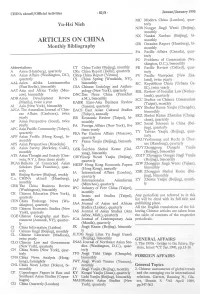

Articles on China

Januar/January 1990 CHINA aktuell/Official Activities - 82/8 - MC Modern China (London), quar Yu-Hsi Nieh terly NJWNongye Jingji Wenti (Beijing), monthly NX Nankai Xuebao (Beijing), bi ARTICLES ON CHINA monthly OR Ostasien Report (Hamburg), bi Monthly Bibliography monthly PA Pacific Affairs (Canada), quar terly PC Problems of Communism (Wa shington, D.C.), bimonthly Abbreviations CT China Today (Beijing), monthly PR Pacific Review (Oxford), quar A Asien (Hamburg), quarterly CRe China Report (Delhi), quarterly terly AA Asian Affairs (Washington, DC), CRep China Report (Vienna) PV Pacific Viewpoint (New Zea- quarterly CS China Spring (Woodside, NY), land), twice yearly AAL Asien Afrika Lateinamerika bimonthly RC Republican China (Urbana Ca (East Berlin), bimonthly CSA Chinese Sociology and Anthro- lif.), twice yearly AATAsia and Africa Today (Mos pology (New York), quarterly RSL Review of Socialist Law (Nether- cow), bimonthly DNCDas Neue China (Frankfurt lands), quarterly ADR Asian Development Review a.M.), bimonthly SCC Studies on Chinese Communism (Manila), twice a year EABR Euro-Asia Business Review (Taipei), monthly AI Asia (New York), bimonthly (Sussex), quarterly SKY Shehui Kexue Yanjiu (Chengdu), AJCA The Australian Journal of Chin EACS East Asian Cultural Studies bimonthly ese Affairs (Canberra), twice (Tokyo), annually SKZ Shehui Kexue Zhanxian (Chang yearly ER Economic Review (Taipei), bi chun), quarterly AP Asian Perspective (Seoul), twice monthly SSC Social Sciences in China (Bei yearly FA Foreign Affairs (New York), -

Uscc 2016 Annual Report

USCC 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 1 2016 REPORT TO CONGRESS of the U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION NOVEMBER 2016 Printed for the use of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.uscc.gov 1 2016 REPORT TO CONGRESS of the U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION NOVEMBER 2016 Printed for the use of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.uscc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION Hon. DENNIS C. SHEA, Chairman CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, Vice Chairman COMMISSIONERS PETER BROOKES DANIEL M. SLANE ROBIN CLEVELAND Hon. JAMES M. TALENT Hon. BYRON L. DORGAN Hon. KATHERINE C. TOBIN JEFFREY L. FIEDLER MICHAEL R. WESSEL Hon. CARTE P. GOODWIN LARRY M. WORTZEL MICHAEL R. DANIS, Executive Director The Commission was created on October 30, 2000, by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Pub. L. No. 106–398, (Oct. 30, 2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001)); as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (re- garding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Pub.