Chapter 1 U.S.-China Economic and Trade Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Event Report

presents 9th Asian Investment Summit Building better portfolios 21-22 May 2014, Ritz-Carlton, Hong Kong Post Event Report 310 delegates representing 190 companies across 18 countries www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Thank You to our sponsors & partners AIWEEK Marquee Sponsors Co-Sponsors Associate Sponsors Workshop Sponsor Supporting Organisations alternative assets. intelligent data. Tech Handset Provider Education Partner Analytics Partner ® Media Partners Offical Broadcast Partner 1 www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Delegate Breakdown 310 delegates representing 190 companies across 18 countries Breakdown by Organisation Institutional Investors 46% Haymarket Financial Media delegate attendee data is Asset Managemer 19% independently verified by the BPA Consultant 8% Fund Distributor / Private Wealth Management 5% Media & Publishing 4% Commercial Bank 4% Index / Trading Platform Provider 3% Association 2% Other 9% Breakdown of Institutional Investors Insurance 31% Endowment / Foundation 27% Corporation 13% Pension Fund 13% Family Office 8% Breakdown by Country Sovereign Wealth Fund 6% PE Funds of Funds 1% Mulitlateral Finance Hong Kong 82% Institution 1% ASEAN 10% North Asia 5% Australia 1% Europe 1% North America 1% Breakdown by Job Function Investment 34% Finance / Treasury 20% Marketing and Investor Relations 19% Other 11% CEO / Managing Director 7% Fund Selection / Distribution 7% Strategist / Economist 2% 2 www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Participating Companies Haymarket Financial Media delegate attendee data is independently verified by the BPA 310 institutonal investors, asset managers, corporates, bankers and advisors attended the Forum. Attending companies included: ACE Life Insurance CFA Institute Board of Governors ACMI China Automation Group Limited Ageas China BOCOM Insurance Co., Ltd. Ageas Hong Kong China Construction Bank Head Office Ageas Insurance Company (Asia) Limited China Life Insurance AIA Chinese YMCA of Hong Kong AIA Group CIC AIA International Limited CIC International (HK) AIA Pension and Trustee Co. -

Allianz Se Allianz Finance Ii B.V. Allianz

2nd Supplement pursuant to Art. 16(1) of Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended (the "Prospectus Directive") and Art. 13 (1) of the Luxembourg Act (the "Luxembourg Act") relating to prospectuses for securities (loi relative aux prospectus pour valeurs mobilières) dated 12 August 2016 (the "Supplement") to the Base Prospectus dated 2 May 2016, as supplemented by the 1st Supplement dated 24 May 2016 (the "Prospectus") with respect to ALLIANZ SE (incorporated as a European Company (Societas Europaea – SE) in Munich, Germany) ALLIANZ FINANCE II B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) ALLIANZ FINANCE III B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) € 25,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme guaranteed by ALLIANZ SE This Supplement has been approved by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (the "CSSF") of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in its capacity as competent authority (the "Competent Authority") under the Luxembourg Act for the purposes of the Prospectus Directive. The Issuer may request the CSSF in its capacity as competent authority under the Luxemburg Act to provide competent authorities in host Member States within the European Economic Area with a certificate of approval attesting that the Supplement has been drawn up in accordance with the Luxembourg Act which implements the Prospectus Directive into Luxembourg law ("Notification"). Right to withdraw In accordance with Article 13 paragraph 2 of the Luxembourg Act, investors who have already agreed to purchase or subscribe for the securities before the Supplement is published have the right, exercisable within two working days after the publication of this Supplement, to withdraw their acceptances, provided that the new factor arose before the final closing of the offer to the public and the delivery of the securities. -

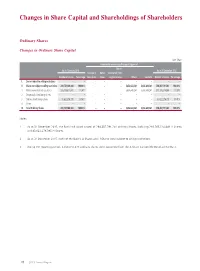

Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders

Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders Ordinary Shares Changes in Ordinary Share Capital Unit: Share Increase/decrease during the reporting period Shares As at 1 January 2015 As at 31 December 2015 Issuance of Bonus transferred from Number of shares Percentage new shares shares surplus reserve Others Sub-total Number of shares Percentage I. Shares subject to selling restrictions – – – – – – – – – II. Shares not subject to selling restrictions 288,731,148,000 100.00% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 294,387,791,241 100.00% 1. RMB-denominated ordinary shares 205,108,871,605 71.04% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 210,765,514,846 71.59% 2. Domestically listed foreign shares – – – – – – – – – 3. Overseas listed foreign shares 83,622,276,395 28.96% – – – – – 83,622,276,395 28.41% 4. Others – – – – – – – – – III. Total Ordinary Shares 288,731,148,000 100.00% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 294,387,791,241 100.00% Notes: 1 As at 31 December 2015, the Bank had issued a total of 294,387,791,241 ordinary shares, including 210,765,514,846 A Shares and 83,622,276,395 H Shares. 2 As at 31 December 2015, none of the Bank’s A Shares and H Shares were subject to selling restrictions. 3 During the reporting period, 5,656,643,241 ordinary shares were converted from the A-Share Convertible Bonds of the Bank. 79 2015 Annual Report Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders Number of Ordinary Shareholders and Shareholdings Number of ordinary shareholders as at 31 December 2015: 963,786 (including 761,073 A-Share Holders and 202,713 H-Share Holders) Number of ordinary shareholders as at the end of the last month before the disclosure of this report: 992,136 (including 789,535 A-Share Holders and 202,601 H-Share Holders) Top ten ordinary shareholders as at 31 December 2015: Unit: Share Number of Changes shares held as Percentage Number of Number of during at the end of of total shares subject shares Type of the reporting the reporting ordinary to selling pledged ordinary No. -

Mizuho China Business Express Economic Journal (No

July 19, 2016 Mizuho Bank (China), Ltd. Corporate Banking Coordination Division ―The macroeconomy― Mizuho China Business Express Economic Journal (No. 58) Summary China’s real GDP (gross domestic product) grew by 6.7% y-o-y in April–June, the same level as January–March. June’s economic indicators were mixed, with some up slightly and some down slightly on May. If moves to eliminate overcapacity and other structural reforms accelerate from the 2H onwards, this will place more downward pressure on the economy. The question is whether China will be able to promote structural reform while maintaining jobs and growth. 1. June’s economic indicators deteriorated slightly on the whole ・ Growth hit +6.7% in April–June too ・ Investment fell slightly ・ Retail sales of consumer goods accelerated slightly ・ Property prices continued to grow at a slower pace in first-tier cities ・ Exports and imports both fell ・ The CPI growth rate slowed, mainly due to stable vegetable prices ・ There was a net increase in new loans, with total social financing also increasing 2. Movement on the employment and earnings environment and to eliminate overcapacity ・ ‘China faces challenges in maintaining household income growth’ (National Bureau of Statistics) ・ ‘Strict penalties will be applied for failure to reach targets for eliminating overcapacity’ (National Development and Reform Commission) - 1 - 1. June’s economic indicators deteriorated slightly on the whole ・Growth hit +6.7% in April–June too On July 15, the National Bureau of Statistics announced that China’s real GDP (gross domestic product) had grown by 6.7% on the same period last year (all figures from here on refer to ‘same-period previous-year’ growth unless otherwise specified) in both January–June and April–June1. -

Allianz Se Allianz Finance Ii B.V

3rd Supplement pursuant to Art. 16(1) of Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended (the "Prospectus Directive") and Art. 13 (1) of the Luxembourg Act (the "Luxembourg Act") relating to prospectuses for securities (loi relative aux prospectus pour valeurs mobilières) dated 25 November 2016 (the "Supplement") to the Base Prospectus dated 2 May 2016, as supplemented by the 1st Supplement dated 24 May 2016 and the 2nd Supplement dated 12 August 2016 (the "Prospectus") with respect to ALLIANZ SE (incorporated as a European Company (Societas Europaea – SE) in Munich, Germany) ALLIANZ FINANCE II B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) ALLIANZ FINANCE III B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) € 25,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme guaranteed by ALLIANZ SE This Supplement has been approved by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (the "CSSF") of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in its capacity as competent authority (the "Competent Authority") under the Luxembourg Act for the purposes of the Prospectus Directive. The Issuer may request the CSSF in its capacity as competent authority under the Luxemburg Act to provide competent authorities in host Member States within the European Economic Area with a certificate of approval attesting that the Supplement has been drawn up in accordance with the Luxembourg Act which implements the Prospectus Directive into Luxembourg law ("Notification"). Right to withdraw In accordance with Article 13 paragraph 2 of the Luxembourg Act, investors who have already agreed to purchase or subscribe for the securities before the Supplement is published have the right, exercisable within two working days after the publication of this Supplement, to withdraw their acceptances, provided that the new factor arose before the final closing of the offer to the public and the delivery of the securities. -

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works. 1 AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/Counterclaim-Defendant, V...., Not Reported in Atl

AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/Counterclaim-Defendant, v...., Not Reported in Atl.... 2020 WL 7024929 Only the Westlaw citation is currently available. MEMORANDUM OPINION UNPUBLISHED OPINION. CHECK *1 AB Stable VIII LLC (“Seller”) is an indirect subsidiary COURT RULES BEFORE CITING. of Dajia Insurance Group, Ltd. (“Dajia”), a corporation organized under the law of the People's Republic of China. Court of Chancery of Delaware. Dajia is the successor to Anbang Insurance Group., Ltd. (“Anbang”), which was also a corporation organized under AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/ the law of the People's Republic of China. For simplicity, Counterclaim-Defendant, and because Anbang was the pertinent entity for much of v. the relevant period, this decision refers to both companies as MAPS HOTELS AND RESORTS ONE LLC, “Anbang.” MIRAE ASSET CAPITAL CO., LTD., MIRAE ASSET DAEWOO CO., LTD., MIRAE ASSET Through Seller, Anbang owns all of the member interests in GLOBAL INVESTMENTS, CO., LTD., and Strategic Hotels & Resorts LLC (“Strategic,” “SHR,” or the MIRAE ASSET LIFE INSURANCE CO., “Company”), a Delaware limited liability company. Strategic in turn owns all of the member interests in fifteen limited LTD., Defendants/Counterclaim-Plaintiffs. liability companies, each of which owns a luxury hotel. C.A. No. 2020-0310-JTL | Under a Sale and Purchase Agreement dated September 10, Date Submitted: October 28, 2020 2019 (the “Sale Agreement” or “SA”), Seller agreed to sell | all of the member interests in Strategic to MAPS Hotel and Date Decided: November 30, 2020 Resorts One LLC (“Buyer”) for a total purchase price of $5.8 billion (the “Transaction”). -

Asian Insurance Industry 2020

PRODUCT DETAILS Included with Purchase y Asian Insurance Industry 2020 y Digital report in PDF format Key findings Knowing Your Insurance Clients y Unlimited online firm-wide access y Analyst support y Exhibits in Excel y Interactive Report Dashboards OVERVIEW & METHODOLOGY This report analyzes Asia’s life insurance industry through the asset management lens. It Interactive Report provides both qualitative and quantitative information, including life insurance assets and Dashboards premiums, asset allocations, investment practices, and outsourcing trends. The report discusses Interact and explore select both institutional (general account) and retail (separate account or investment-linked product) report data with Cerulli’s segments, and covers China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, visualization tool. and Indonesia. The report also details key factors that influence insurers’ investments, such as regulations, asset-liability management, products, distribution landscapes, and other key developments. In addition to covering two region-wide themes on insurtech for distribution and investments y Asian Insurance Investment Landscape: in the low-interest-rate-environment, the report provides in-depth analysis of Asia ex-Japan y Review five years of historical life insurance premiums, assets, and insurance markets, capturing trends in both chart and text forms. investable assets in Asia ex-Japan by region and country, and view growth rates by asset type. USE THIS REPORT TO y Analyze the marketshare of life insurance -

2019 Insurance Fact Book

2019 Insurance Fact Book TO THE READER Imagine a world without insurance. Some might say, “So what?” or “Yes to that!” when reading the sentence above. And that’s understandable, given that often the best experience one can have with insurance is not to receive the benefits of the product at all, after a disaster or other loss. And others—who already have some understanding or even appreciation for insurance—might say it provides protection against financial aspects of a premature death, injury, loss of property, loss of earning power, legal liability or other unexpected expenses. All that is true. We are the financial first responders. But there is so much more. Insurance drives economic growth. It provides stability against risks. It encourages resilience. Recent disasters have demonstrated the vital role the industry plays in recovery—and that without insurance, the impact on individuals, businesses and communities can be devastating. As insurers, we know that even with all that we protect now, the coverage gap is still too big. We want to close that gap. That desire is reflected in changes to this year’s Insurance Information Institute (I.I.I.)Insurance Fact Book. We have added new information on coastal storm surge risk and hail as well as reinsurance and the growing problem of marijuana and impaired driving. We have updated the section on litigiousness to include tort costs and compensation by state, and assignment of benefits litigation, a growing problem in Florida. As always, the book provides valuable information on: • World and U.S. catastrophes • Property/casualty and life/health insurance results and investments • Personal expenditures on auto and homeowners insurance • Major types of insurance losses, including vehicle accidents, homeowners claims, crime and workplace accidents • State auto insurance laws The I.I.I. -

Institutional Asset Management in Asia 2020

PRODUCT DETAILS Included with Purchase y Institutional Asset Management in Asia 2020 y Digital report in PDF format Key findings Setting the Stage for a New Era y Unlimited online firm-wide access y Analyst support y Exhibits in Excel y Interactive Report Dashboards OVERVIEW & METHODOLOGY This report takes a comprehensive examination of the Asia-Pacific region’s institutional Interactive Report landscape and outsourcing opportunities for external asset managers. It builds on our Dashboards previous research on Asian pensions, sovereign wealth funds, insurers, and other institutions, Interact and explore select and complements all our other Asian publications. The report focuses on market sizing and report data with Cerulli’s addressability, institutions’ investment behavior, strategies and allocation plans, outsourcing visualization tool. practices, manager selection, use of consultants, and other trends in Asia’s institutional asset management industry. The report explores three region-wide themes—the evolution of institutional sales, demand for alternative strategies, and de-risking and liquidity management among institutions. It y Regional Overview: Compare institutional market sizing in the also assesses the opportunities and challenges in the Australia and New Zealand institutional Asia-Pacific region, which includes investable assets by market, markets. This is followed by in-depth analysis of the institutional markets of China, Hong Kong, year, and institution type, as well as forecasted investable and Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. addressable assets. y Institutional Type Analysis: Evaluate and compare the USE THIS REPORT TO retirement, insurance, and sovereign wealth fund markets in Asia ex-Japan, with interactive data covering investable and addressable y Analyze insourcing and fintech adoption trends among Asian institutions and how managers assets segmented by year, investment objective, and asset class. -

2017 China Insurance Review

2017 Insurance Review FEBRUARY 2018 Thomas P. Fitzgerald Chairman Winston & Strawn LLP Foreword The continued growth of China’s insurance market means more opportunities for established and new insurance companies and insurance intermediaries looking to expand or create a foothold there. Winston & Strawn, a leading expert in cross-border M&A, contentious, and regulatory work, established offices in Hong Kong in 2008 and in Shanghai in 2009 in order to better serve our clients that operate in Asia. Our presence in Hong Kong and Mainland China has allowed us to broaden our services and extend the reach of our practices to include insurance expertise for the PRC. I hope that you find this booklet useful. Please feel free to reach out to our China team should you have any questions or require any additional information. You will find their contact details at the end of this booklet. Attorney advertising materials – © 2018 Winston & Strawn LLP 1. Introduction The overall outlook for China’s insurance industry has enjoyed robust growth in recent years. Total premium income, for example, China is healthy and rose 27.5% in 2016 to reach RMB 3.1 trillion (USD 490 billion), the strongest growth the industry has enjoyed statistics for 2017 show since 2008. As well, by the end of 2016, total insurance industry assets stood at RMB 15.12 trillion (USD 2.39 that overall insurance trillion), a 22.3% increase from the start of the year. Premium growth slowed in 2017 due in large part to premium income rose China Insurance Regulatory Commission (“CIRC”) reforms aimed at universal life insurance. -

Qualified Domestic Institutional Investors(Qdiis) with Investment Quotas Granted by the SAFE

Qualified Domestic Institutional Investors(QDIIs) with Investment Quotas Granted by the SAFE By September30, 2019 Unit: 100 million USD No. Name of QDII Latest Approval Date Investment Quota 1 Bank of China, Ltd. 2018.06.28 8.00 Industrial and Commercial Bank of 2 2018.05.30 8.00 China Limited 3 Bank of East Asia (China), Ltd. 2014.12.28 2.00 4 Bank of Communications Co., Ltd. 2006.07.27 5.00 5 China Construction Bank Corporation 2014.12.28 5.00 6 HSBC Bank (China) Company, Ltd. 2015.03.26 34.00 7 China Merchants Bank Co., Ltd. 2014.12.28 2.00 8 China Citic Bank 2006.09.18 1.00 9 Hang Seng Bank (China) Company, Ltd. 2006.09.27 0.30 10 Citibank (China) Co., Ltd. 2006.09.27 34.00 11 Industrial Bank 2014.12.28 1.00 12 Standard Chartered Bank (China), Ltd. 2015.01.30 20.00 13 Minsheng Bank 2006.11.08 1.00 14 China Everbright Bank 2014.12.28 1.00 15 Bank of Beijing 2006.12.11 0.50 Bank of China (Hong Kong), Ltd. 16 2007.01.11 0.30 Branches in Mainland 17 Credit Suisse Shanghai Branch 2007.01.30 0.30 18 Agricultural Bank of China 2014.12.28 2.00 19 Nanyang Commercial Bank (China) Co., 2015.02.13 1.80 20 DeutscheLtd. Bank (China) Co., Ltd. 2007.08.17 0.30 21 Shanghai Pudong Development Bank 2007.08.31 0.30 22 Bank of Shanghai 2008.01.24 0.30 23 DBS Bank (China), Ltd. -

Cronología China 2020

Cronología China 2020 Enero 01.01. Entra en vigor la Ley de Inversión Extranjera. El Banco Central anuncia un recorte de 50 puntos básicos en el coeficiente de reserva obligatoria para las instituciones financieras. Nueva regulación para mejorar el entorno empresarial. Discurso de Año Nuevo de la presidenta taiwanesa, Tsai Ing-wen. 02.01. Xi Jinping firma una orden de movilización nacional para el entrenamiento de las fuerzas armadas. Hu Chunhua insiste en más esfuerzos para ganar la batalla contra la pobreza. Grave accidente de un helicóptero militar en Taiwán en el que fallece el Jefe del Estado Mayor para la Defensa, Shen Yi-ming, y otras siete personas más. 03.01. Xi Jinping preside la sexta reunión del Comité Central del PCCh para asuntos económicos y financieros. Wang Huning centra la publicidad en el logro de la sociedad modestamente acomodada. Informan de manifestaciones y detenciones en Hong Kong. China planea hasta 50 misiones de lanzamiento espacial en 2020. Beijing pide moderación en las tensiones entre EEUU e Irán. 04.01. El presidente de Kiribbati, Taneti Mamau, inicia una visita de Estado a China. Luo Huining, nuevo director de la Oficina de Enlace en Hong Kong. Se intensifican los rumores sobre el estallido de una nueva epidemia de SARS en Wuhan. Altos funcionarios de Shaanxi son expulsados del PCCh. Wang Yi conversa telefónicamente con su homologo ruso Lavrov sobre la crisis en Oriente Medio. Taiwán a la cabeza en Asia en términos de igualdad de género. 1 Grupos laborales se manifiestan en Taipéi para exigir a los partidos atención a las políticas en esta materia.