August 2017 Trade Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Event Report

presents 9th Asian Investment Summit Building better portfolios 21-22 May 2014, Ritz-Carlton, Hong Kong Post Event Report 310 delegates representing 190 companies across 18 countries www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Thank You to our sponsors & partners AIWEEK Marquee Sponsors Co-Sponsors Associate Sponsors Workshop Sponsor Supporting Organisations alternative assets. intelligent data. Tech Handset Provider Education Partner Analytics Partner ® Media Partners Offical Broadcast Partner 1 www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Delegate Breakdown 310 delegates representing 190 companies across 18 countries Breakdown by Organisation Institutional Investors 46% Haymarket Financial Media delegate attendee data is Asset Managemer 19% independently verified by the BPA Consultant 8% Fund Distributor / Private Wealth Management 5% Media & Publishing 4% Commercial Bank 4% Index / Trading Platform Provider 3% Association 2% Other 9% Breakdown of Institutional Investors Insurance 31% Endowment / Foundation 27% Corporation 13% Pension Fund 13% Family Office 8% Breakdown by Country Sovereign Wealth Fund 6% PE Funds of Funds 1% Mulitlateral Finance Hong Kong 82% Institution 1% ASEAN 10% North Asia 5% Australia 1% Europe 1% North America 1% Breakdown by Job Function Investment 34% Finance / Treasury 20% Marketing and Investor Relations 19% Other 11% CEO / Managing Director 7% Fund Selection / Distribution 7% Strategist / Economist 2% 2 www.AsianInvestmentSummit.com Participating Companies Haymarket Financial Media delegate attendee data is independently verified by the BPA 310 institutonal investors, asset managers, corporates, bankers and advisors attended the Forum. Attending companies included: ACE Life Insurance CFA Institute Board of Governors ACMI China Automation Group Limited Ageas China BOCOM Insurance Co., Ltd. Ageas Hong Kong China Construction Bank Head Office Ageas Insurance Company (Asia) Limited China Life Insurance AIA Chinese YMCA of Hong Kong AIA Group CIC AIA International Limited CIC International (HK) AIA Pension and Trustee Co. -

Allianz Se Allianz Finance Ii B.V. Allianz

2nd Supplement pursuant to Art. 16(1) of Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended (the "Prospectus Directive") and Art. 13 (1) of the Luxembourg Act (the "Luxembourg Act") relating to prospectuses for securities (loi relative aux prospectus pour valeurs mobilières) dated 12 August 2016 (the "Supplement") to the Base Prospectus dated 2 May 2016, as supplemented by the 1st Supplement dated 24 May 2016 (the "Prospectus") with respect to ALLIANZ SE (incorporated as a European Company (Societas Europaea – SE) in Munich, Germany) ALLIANZ FINANCE II B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) ALLIANZ FINANCE III B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) € 25,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme guaranteed by ALLIANZ SE This Supplement has been approved by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (the "CSSF") of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in its capacity as competent authority (the "Competent Authority") under the Luxembourg Act for the purposes of the Prospectus Directive. The Issuer may request the CSSF in its capacity as competent authority under the Luxemburg Act to provide competent authorities in host Member States within the European Economic Area with a certificate of approval attesting that the Supplement has been drawn up in accordance with the Luxembourg Act which implements the Prospectus Directive into Luxembourg law ("Notification"). Right to withdraw In accordance with Article 13 paragraph 2 of the Luxembourg Act, investors who have already agreed to purchase or subscribe for the securities before the Supplement is published have the right, exercisable within two working days after the publication of this Supplement, to withdraw their acceptances, provided that the new factor arose before the final closing of the offer to the public and the delivery of the securities. -

Climate-Change Journalism in China: Opportunities for International

Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation By Sam Geall Foreword by Hu Shuli 中国气候变化报道: 国际合作中的机遇 山姆·吉尔 序——胡舒立 Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation 中国气候变化报道:国际合作中的机遇 © International Media Support 2011. Any reproduction, modification, publication, transmission, transfer, sale distribution, display or exploitation of this information, in any form or by any means, or its storage in a retrieval system, whether in whole or in part, without the express written permission of the individual copyright holder is prohibited without prior approval by IMS. Cover image by Angel Hsu. © 国际媒体支持组织 版权所有 2011 任何媒体、网站或个人未经“国际媒体支持组织”的书面许可,不得引用、复 制、转载、摘编、发售、储存于检索系统,或以其他任何方式非法使用本报告全 部或部分内容。 封面照片由徐安琪摄。 International Media Support (IMS) Communications Unit, Nørregade 18, Copenhagen K 1165, Denmark Phone: +4588327000, Fax: +4533120099 Email: [email protected] www.i-m-s.dk Caixin Media Floor 15/16, Tower A, Winterless Center, No.1 Xidawanglu, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, P.R.China http://english.caing.com/ chinadialogue Suite 306 Grayston Centre, 28 Charles Square, London N1 6HT, United Kingdom Phone: +442073244767 Email: [email protected] www.chinadialogue.net Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation By Sam Geall1 Foreword by Hu Shuli2 p4 1. Sam Geall is deputy editor of chinadialogue. The author acknowledges generous contributions to the research and analysis in this report from Li Hujun, Wang Haotong, Eliot Gao and Lisa Lin. Essential input and support were also provided by Martin Breum, Martin Gottske, Isabel Hilton, Tan Copsey, Li Dawei, Ma Ling, Hu Shuli, Bruce Lewenstein and Jia Hepeng. 2. Hu Shuli is editor-in-chief of Caixin Media (the Beijing-based media group that publishes Century Weekly and China Reform), the former founding editor of Caijing magazine and a prominent investigative journalist and commentator. -

Incentives in China's Reformation of the Sports Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keck Graduate Institute Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Yu Fu Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Fu, Yu, "Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1609. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1609 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Submitted to Professor Minxin Pei by Yu Fu for Senior Thesis Spring 2017 April 24, 2017 2 Abstract Since the 2010s, China’s sports industry has undergone comprehensive reforms. This paper attempts to understand this change of direction from the central state’s perspective. By examining the dynamics of the basketball and soccer markets, it discovers that while the deregulation of basketball is a result of persistent bottom-up effort from the private sector, the recentralization of soccer is a state-led policy change. Notwithstanding the different nature and routes between these reforms, in both sectors, the state’s aim is to restore and strengthen its legitimacy within the society. Amidst China’s economic stagnation, the regime hopes to identify sectors that can drive sustainable growth, and to make adjustments to its bureaucracy as a way to respond to the society’s mounting demand for political modernization. -

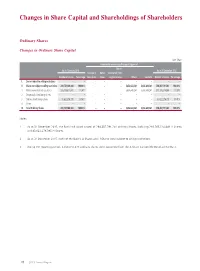

Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders

Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders Ordinary Shares Changes in Ordinary Share Capital Unit: Share Increase/decrease during the reporting period Shares As at 1 January 2015 As at 31 December 2015 Issuance of Bonus transferred from Number of shares Percentage new shares shares surplus reserve Others Sub-total Number of shares Percentage I. Shares subject to selling restrictions – – – – – – – – – II. Shares not subject to selling restrictions 288,731,148,000 100.00% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 294,387,791,241 100.00% 1. RMB-denominated ordinary shares 205,108,871,605 71.04% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 210,765,514,846 71.59% 2. Domestically listed foreign shares – – – – – – – – – 3. Overseas listed foreign shares 83,622,276,395 28.96% – – – – – 83,622,276,395 28.41% 4. Others – – – – – – – – – III. Total Ordinary Shares 288,731,148,000 100.00% – – – 5,656,643,241 5,656,643,241 294,387,791,241 100.00% Notes: 1 As at 31 December 2015, the Bank had issued a total of 294,387,791,241 ordinary shares, including 210,765,514,846 A Shares and 83,622,276,395 H Shares. 2 As at 31 December 2015, none of the Bank’s A Shares and H Shares were subject to selling restrictions. 3 During the reporting period, 5,656,643,241 ordinary shares were converted from the A-Share Convertible Bonds of the Bank. 79 2015 Annual Report Changes in Share Capital and Shareholdings of Shareholders Number of Ordinary Shareholders and Shareholdings Number of ordinary shareholders as at 31 December 2015: 963,786 (including 761,073 A-Share Holders and 202,713 H-Share Holders) Number of ordinary shareholders as at the end of the last month before the disclosure of this report: 992,136 (including 789,535 A-Share Holders and 202,601 H-Share Holders) Top ten ordinary shareholders as at 31 December 2015: Unit: Share Number of Changes shares held as Percentage Number of Number of during at the end of of total shares subject shares Type of the reporting the reporting ordinary to selling pledged ordinary No. -

The Coronavirus Cover-Up: a Timeline

SITUATION BRIEF April 10, 2020 • China Studies Program The Coronavirus Cover-Up: A Timeline How the Chinese Communist Party Misled the World about COVID-19 and Is Using the World Health Organization As an Instrument of Propaganda Executive Summary The People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its ruling Chi- assertions, the harm would have been significantly reduced. nese Communist Party (CCP) have deceived the world Instead, the PRC’s actions and WHO’s inaction precipitat- about the coronavirus since its appearance in late 2019. In ed a pandemic, leading to a global economic crisis and a this situation brief, the Victims of Communism Memorial growing loss of human life. Foundation compares the timeline and facts with China’s ongoing disinformation campaign about the coronavirus’ As a matter of justice, and to prevent future pandemics, the origins, nature, and spread. This brief also demonstrates PRC must be held accountable through demands for eco- how the World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted nomic reparations and other sanctions pertaining to human and helped legitimize China’s false claims. rights. China should also be suspended from full member- ship in the WHO and the WHO, which U.S. taxpayers fund The consequences of China’s deception and the WHO’s cre- annually, must be subject to immediate investigation and re- dulity are now playing out globally. It is normally difficult to form. Media organizations reporting on the claims of China assign culpability to governments and organizations charged and WHO regarding the pandemic without scrutiny or con- with ensuring public health in any pandemic, but the coro- text must be cautioned against misleading the public. -

Allianz Se Allianz Finance Ii B.V

3rd Supplement pursuant to Art. 16(1) of Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended (the "Prospectus Directive") and Art. 13 (1) of the Luxembourg Act (the "Luxembourg Act") relating to prospectuses for securities (loi relative aux prospectus pour valeurs mobilières) dated 25 November 2016 (the "Supplement") to the Base Prospectus dated 2 May 2016, as supplemented by the 1st Supplement dated 24 May 2016 and the 2nd Supplement dated 12 August 2016 (the "Prospectus") with respect to ALLIANZ SE (incorporated as a European Company (Societas Europaea – SE) in Munich, Germany) ALLIANZ FINANCE II B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) ALLIANZ FINANCE III B.V. (incorporated with limited liability in Amsterdam, The Netherlands) € 25,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme guaranteed by ALLIANZ SE This Supplement has been approved by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (the "CSSF") of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in its capacity as competent authority (the "Competent Authority") under the Luxembourg Act for the purposes of the Prospectus Directive. The Issuer may request the CSSF in its capacity as competent authority under the Luxemburg Act to provide competent authorities in host Member States within the European Economic Area with a certificate of approval attesting that the Supplement has been drawn up in accordance with the Luxembourg Act which implements the Prospectus Directive into Luxembourg law ("Notification"). Right to withdraw In accordance with Article 13 paragraph 2 of the Luxembourg Act, investors who have already agreed to purchase or subscribe for the securities before the Supplement is published have the right, exercisable within two working days after the publication of this Supplement, to withdraw their acceptances, provided that the new factor arose before the final closing of the offer to the public and the delivery of the securities. -

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works. 1 AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/Counterclaim-Defendant, V...., Not Reported in Atl

AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/Counterclaim-Defendant, v...., Not Reported in Atl.... 2020 WL 7024929 Only the Westlaw citation is currently available. MEMORANDUM OPINION UNPUBLISHED OPINION. CHECK *1 AB Stable VIII LLC (“Seller”) is an indirect subsidiary COURT RULES BEFORE CITING. of Dajia Insurance Group, Ltd. (“Dajia”), a corporation organized under the law of the People's Republic of China. Court of Chancery of Delaware. Dajia is the successor to Anbang Insurance Group., Ltd. (“Anbang”), which was also a corporation organized under AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/ the law of the People's Republic of China. For simplicity, Counterclaim-Defendant, and because Anbang was the pertinent entity for much of v. the relevant period, this decision refers to both companies as MAPS HOTELS AND RESORTS ONE LLC, “Anbang.” MIRAE ASSET CAPITAL CO., LTD., MIRAE ASSET DAEWOO CO., LTD., MIRAE ASSET Through Seller, Anbang owns all of the member interests in GLOBAL INVESTMENTS, CO., LTD., and Strategic Hotels & Resorts LLC (“Strategic,” “SHR,” or the MIRAE ASSET LIFE INSURANCE CO., “Company”), a Delaware limited liability company. Strategic in turn owns all of the member interests in fifteen limited LTD., Defendants/Counterclaim-Plaintiffs. liability companies, each of which owns a luxury hotel. C.A. No. 2020-0310-JTL | Under a Sale and Purchase Agreement dated September 10, Date Submitted: October 28, 2020 2019 (the “Sale Agreement” or “SA”), Seller agreed to sell | all of the member interests in Strategic to MAPS Hotel and Date Decided: November 30, 2020 Resorts One LLC (“Buyer”) for a total purchase price of $5.8 billion (the “Transaction”). -

COVID-19 and China: a Chronology of Events (December 2019-January 2020)

COVID-19 and China: A Chronology of Events (December 2019-January 2020) Updated May 13, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46354 SUMMARY R46354 COVID-19 and China: A Chronology of Events May 13, 2020 (December 2019-January 2020) Susan V. Lawrence In Congress, multiple bills and resolutions have been introduced related to China’s Specialist in Asian Affairs handling of a novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China, that expanded to become the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic. This report provides a timeline of key developments in the early weeks of the pandemic, based on available public reporting. It also considers issues raised by the timeline, including the timeliness of China’s information sharing with the World Health Organization (WHO), gaps in early information China shared with the world, and episodes in which Chinese authorities sought to discipline those who publicly shared information about aspects of the epidemic. Prior to January 20, 2020—the day Chinese authorities acknowledged person-to-person transmission of the novel coronavirus—the public record provides little indication that China’s top leaders saw containment of the epidemic as a high priority. Thereafter, however, Chinese authorities appear to have taken aggressive measures to contain the virus. The Appendix includes a concise version of the timeline. A condensed version is below: Late December: Hospitals in Wuhan, China, identify cases of pneumonia of unknown origin. December 30: The Wuhan Municipal Health Commission issues “urgent notices” to city hospitals about cases of atypical pneumonia linked to the city’s Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. The notices leak online. -

Asian Insurance Industry 2020

PRODUCT DETAILS Included with Purchase y Asian Insurance Industry 2020 y Digital report in PDF format Key findings Knowing Your Insurance Clients y Unlimited online firm-wide access y Analyst support y Exhibits in Excel y Interactive Report Dashboards OVERVIEW & METHODOLOGY This report analyzes Asia’s life insurance industry through the asset management lens. It Interactive Report provides both qualitative and quantitative information, including life insurance assets and Dashboards premiums, asset allocations, investment practices, and outsourcing trends. The report discusses Interact and explore select both institutional (general account) and retail (separate account or investment-linked product) report data with Cerulli’s segments, and covers China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, visualization tool. and Indonesia. The report also details key factors that influence insurers’ investments, such as regulations, asset-liability management, products, distribution landscapes, and other key developments. In addition to covering two region-wide themes on insurtech for distribution and investments y Asian Insurance Investment Landscape: in the low-interest-rate-environment, the report provides in-depth analysis of Asia ex-Japan y Review five years of historical life insurance premiums, assets, and insurance markets, capturing trends in both chart and text forms. investable assets in Asia ex-Japan by region and country, and view growth rates by asset type. USE THIS REPORT TO y Analyze the marketshare of life insurance -

2019 Insurance Fact Book

2019 Insurance Fact Book TO THE READER Imagine a world without insurance. Some might say, “So what?” or “Yes to that!” when reading the sentence above. And that’s understandable, given that often the best experience one can have with insurance is not to receive the benefits of the product at all, after a disaster or other loss. And others—who already have some understanding or even appreciation for insurance—might say it provides protection against financial aspects of a premature death, injury, loss of property, loss of earning power, legal liability or other unexpected expenses. All that is true. We are the financial first responders. But there is so much more. Insurance drives economic growth. It provides stability against risks. It encourages resilience. Recent disasters have demonstrated the vital role the industry plays in recovery—and that without insurance, the impact on individuals, businesses and communities can be devastating. As insurers, we know that even with all that we protect now, the coverage gap is still too big. We want to close that gap. That desire is reflected in changes to this year’s Insurance Information Institute (I.I.I.)Insurance Fact Book. We have added new information on coastal storm surge risk and hail as well as reinsurance and the growing problem of marijuana and impaired driving. We have updated the section on litigiousness to include tort costs and compensation by state, and assignment of benefits litigation, a growing problem in Florida. As always, the book provides valuable information on: • World and U.S. catastrophes • Property/casualty and life/health insurance results and investments • Personal expenditures on auto and homeowners insurance • Major types of insurance losses, including vehicle accidents, homeowners claims, crime and workplace accidents • State auto insurance laws The I.I.I. -

Mapping the EU-China Cultural and Creative Landscape

MAPPING THE EU‐CHINA CULTURAL AND CREATIVE LANDSCAPE A joint mapping study prepared for the Ministry of Culture (MoC) of the People's Republic of China and DG Education and Culture (EAC) of the European Commission September 2015 1 CO-AUTHORS: Chapters I to III: Cui Qiao - Senior Expert, BMW Foundation China Representative, Founder China Contemporary Art Foundation Huang Shan - Junior Expert, Founder Artspy.cn Chapter IV: Katja Hellkötter - Senior Expert, Founder & Director, CONSTELLATIONS International Léa Ayoub - Junior Expert, Project Manager, CONSTELLATIONS International http://www.constellations-international.com Disclaimer This mapping study has been produced in the context and with the support of the EU-China Policy Dialogues Support Facility (PDSF II), a project financed jointly by the European Union and the Government of the People's Republic of China, implemented by a consortium led by Grontmij A/S. This consolidated version is based on the contributions of the two expert teams mentioned above and has been finalised by the European Commission (DG EAC). The content does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Directorate General Education and Culture (DG EAC) or the Ministry of Culture (MoC) of the People’s Republic of China. DG EAC and MoC are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. The authors have produced this study to the best of their ability and knowledge; nevertheless they assume no liability for any damages, material or immaterial, that may arise from the use of this study or its content. 2 Contents I. General Introduction ....................................................................................................... 5 1. Background .............................................................................................................................. 5 2. Project Description .................................................................................................................